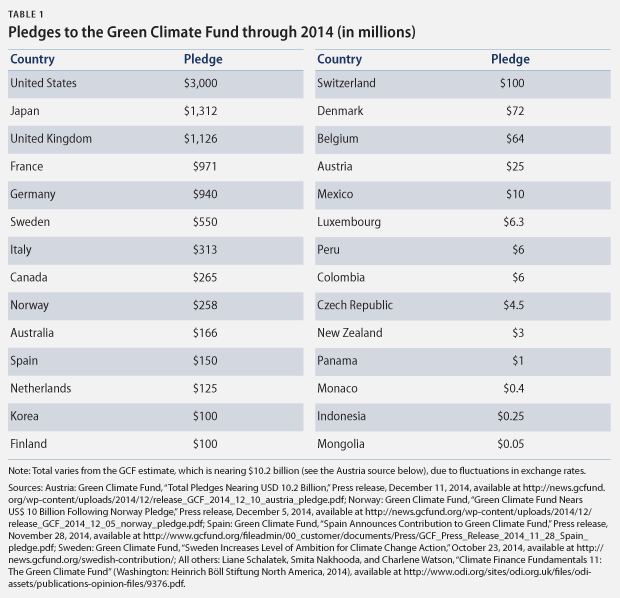

In his fiscal year 2016 budget, President Barack Obama requested $500 million for the new Green Climate Fund, or GCF—an important step toward fulfilling the $3 billion pledge the United States made to the fund in November 2014.

The GCF is a multilateral fund designed to invest in projects that help developing countries shift to pathways of low-carbon and climate-resilient growth. During the U.N. climate conference in December, the fund surpassed its goal of reaching $10 billion in pledges toward its initial capitalization. It now has commitments from more than 25 countries and is ready to begin approving projects later this year.

Congress should fulfill the president’s request for GCF funding, as the fund is well positioned to make progress on its important mission for the following reasons:

- The fund has a mandate to help countries adapt and enhance their resilience to the impacts of climate change. Historically, funding for adaptation has been overshadowed by funding for mitigating greenhouse gas pollution. In 2013, 91 percent of total climate finance went toward emissions mitigation.

- With a record of attracting pledges from developing countries—including Mexico, Peru, and Colombia—the GCF is the first multilateral platform to foretell a new paradigm of climate finance in which traditional donors and capable emerging economies jointly facilitate the transition to a low-carbon global economy.

- The new international climate agreement slated for December 2015 needs broad and meaningful participation to successfully rein in world emissions. Support for the GCF helps facilitate this by demonstrating the commitment of developed countries to assist vulnerable regions.

- The GCF includes a private-sector facility with the directive to unlock private capital—thereby multiplying the initial public investment. The private sector has already demonstrated its promise in funding climate efforts by providing $193 billion in climate finance in 2013.

- The GCF will incorporate lessons learned from the Climate Investment Funds, or CIFs, including lessons learned in mobilizing private finance. The CIFs are a precursor to the GCF that have been designed to sunset when the GCF comes on-line.

In addition, support for the GCF would continue a strong legacy of U.S. leadership on multilateral climate finance. The United States has consistently supported the Global Environment Facility, or GEF—which funds projects related to climate change, land degradation, water, and other challenges—through both Democratic and Republican administrations and Congresses. It has also funded the CIFs—launched under former President George W. Bush—every year. Now is not the time to damage that legacy.

In initial congressional debates about GCF funding, some have worried about spending public dollars on international efforts when the United States has its own adaptation needs. For example, Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R-AK) recently proposed in an amendment to the bill to approve the Keystone XL pipeline that any funds for adaptation should be spent domestically and that GCF funding should instead be spent on building climate resilience in Alaskan and rural communities.

Concern for the United States and the Arctic in the face of climate change is well founded. Adverse climate impacts—such as water shortages, declines in crop productivity, and damage from extreme weather—now affect every region in the country. And the rate of warming in the Arctic region is twice the global average, which threatens more than 180 Alaska Native villages, as well as infrastructure throughout the state.

The administration has demonstrated its dedication to building domestic resilience in the FY 2016 budget by proposing hundreds of millions of dollars for programs such as coastal resilience, drought-resistant agriculture, and wildfire suppression. The budget also allocates $50 million specifically for community resilience efforts in Alaska Native villages and American Indian tribes.

But funding these vital domestic efforts simply by raiding the international climate budget would be robbing Peter to pay Paul. In reality, supporting adaptation and mitigation globally is not only compatible with domestic climate safety but also is necessary to achieve it.

Without efforts to decouple global growth and carbon pollution around the world, the economic and human costs of climate change in the United States would increase along with increasing global temperatures. In order to rein in further warming and therefore additional domestic costs, the International Energy Agency found that global investments in clean energy and energy efficiency must double to nearly $790 billion per year by 2020.

In addition, without efforts to build climate resilience globally, the United States’ international development efforts and broader national security objectives would be, at best, sorely undermined. Climate change, according to World Bank President Jim Yong Kim, is “a fundamental threat to development in our lifetime.” “We know that if we don’t confront climate change,” he said in December 2014, “there will be no hope of ending poverty or boosting shared prosperity.” Moreover, the U.S. Department of Defense recognizes that climate change can lead to regional instability and even extremism. According to Navy Adm. Samuel J. Locklear III, for instance, climate impacts pose the greatest security threat in the Pacific.

Yes, policymakers must fund domestic adaptation efforts to cope with the impacts of climate change that it is already too late to avert. But they will not accomplish their goal by turning a blind eye to the broader effort of building the international response to climate change.

Pete Ogden is a Senior Fellow and the Director of International Energy and Climate Policy at the Center for American Progress. Gwynne Taraska is a Senior Policy Advisor working on climate and energy policy for the Center.