This report contains a correction.

Introduction and summary

Benton County, Mississippi—which sits on the Tennessee border 70 miles outside of Memphis—has one of the highest parental employment rates in the state. In fact, more than 97 percent of young children have a working parent.1 More than half of 3- and 4-year-old children in Benton County are enrolled in preschool, and unlike many other rural parts of the country, the county is not considered a “child care desert”—a region with a significant undersupply of child care.2 However, while not lacking in child care overall, a closer look shows that the supply of such care poses a problem for many families in Benton: There is not a single licensed child care provider in the entire county that enrolls infants or toddlers.3

In this sense, Benton County demonstrates a common issue facing the child care market. Too often, families face a scarcity of options when they look for child care for a new baby or young toddler.

Nearly 60 percent of mothers with a child younger than age 3 are employed.4 With about 4 million babies born every year in the United States, there is a high demand for infant and toddler child care.5 In a recent survey, 83 percent of parents with children younger than age 6 stated that finding quality affordable child care is a problem in their area.6 This percentage is likely greater for the parents of infants and toddlers. Another recent survey indicated that younger children’s parents are more likely to report lack of availability as the primary reason for difficulty finding care.7

Providing high-quality child care is expensive—especially for infants and toddlers—making it difficult for the child care market to respond to the needs of parents who cannot afford high prices. Safe and age-appropriate care for the youngest children requires low staff ratios and small group sizes, which are costly to deliver.8 The average cost of providing infant care in the United States is estimated at nearly $15,000 per year, more than 20 percent of the typical family’s income.9 Meanwhile, child care assistance reaches only a fraction of eligible families, and even when available, it is rarely sufficient to cover the cost of providing infant and toddler care.10

This shortage of licensed child care can have a significant impact on children and their families. Parents may be forced to make tradeoffs that result in less engaging and reliable child care for their children or that harm their family’s economic security. Without affordable, licensed child care, some families rely on a patchwork of child care arrangements that do not fully meet their family’s needs. For children, this happens during a particularly important time for child development, as the interactions they have with caregivers in the first three years of life can have long-term effects that lay the groundwork for healthy socio-emotional regulation, learning ability, and resilience.

Building on previous child care deserts analysis conducted by the Center for American Progress,11 this study quantifies the extent of this problem by analyzing the availability of licensed child care for infants and toddlers in nine states and the District of Columbia.12 The study finds that in these states:

- There are more than five infants and toddlers for every licensed child care slot. This is more than three times the ratio for 3- through- 5-year-olds.13

- Using the Center for American Progress’ working definition for child care deserts—places where there are three or more children for each licensed child care slot—more than 95 percent of the counties in this study would be classified as an infant and toddler child care desert.

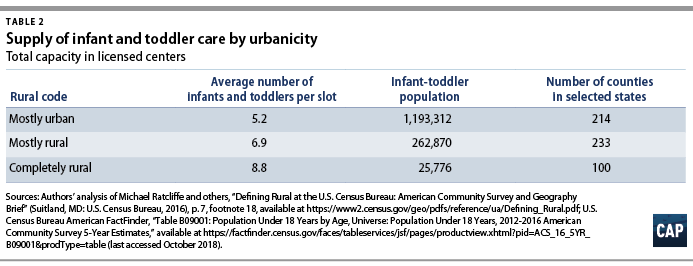

- While child care shortages for infants and toddlers exist everywhere, they are especially pronounced in rural areas and counties with lower median family incomes. There are nine children under 3 for every child care slot in completely rural counties, compared with five per slot in mostly urban counties.

These results confirm what many parents have known for years: Finding licensed child care for infants and toddlers is extremely challenging. Even if just half of the infants and toddlers in these states required child care, on average, there would still only be enough licensed capacity for 1 in every 3 children. As a result, many working families instead opt for unlicensed programs or family, friend, or neighbor care.14

Understanding the demand for child care and the limitations of the current market to support the needs of infants and toddlers is an important first step in addressing the problem. This study concludes with a series of recommendations for how policymakers can act to better support children, families, and early childhood providers in order to ensure that all families can access the child care they need.

Making affordable, high-quality child care for infants and toddlers available to all families would have significant benefits for children, parents, and the country as a whole. Parents would no longer be forced to spend weeks searching for child care and paying waitlist fees in the hope of securing a space or stretching their sick leave and vacation time when child care options fall through.15 Instead, they could drop their children off in the same place every day, knowing they are leaving them in a familiar, nurturing, and stimulating environment while they continue to work and advance their careers, staying afloat financially during a particularly expensive time.16

The infant-toddler child care landscape

Every day, thousands of families across the United States welcome a new baby into their lives. Between diapers, baby food, clothes, car seats, and the many other necessities a newborn requires, new parents are often financially strapped. However, the largest expenditure for many families is child care, which can easily exceed $10,000 per year.17 Unfortunately, even if families can afford this high cost, many struggle to simply find a program with space available for their child. Waitlists are long, options are limited, and in many communities, parents have to start assessing their options many months before they actually need care.

So why is child care supply so limited, especially for infants and toddlers? The answer comes down to money, as providing quality care is expensive. Decades of brain science have shown the tremendous development that occurs in the first three years of life, and caregivers are second only to parents in the influence they can have on this development.18 To recruit and train the highly skilled educators who are critical to children’s development, programs must pay teachers compensation that matches the expectations of the job. A highly skilled and experienced teacher can maximize learning opportunities for all children, ensuring that child care sets children on a trajectory for future success.

The youngest children require the most attention from caregivers, making low staff ratios and small group sizes essential for providing a safe and enriching child care environment. However, the small group sizes in infant and toddler classrooms mean there is less revenue available to cover the cost of adequate teacher salaries and benefits. For instance, a preschool classroom typically includes 20 children, whose families pay tuition to cover the salary of two teachers, whereas an infant classroom may only have six or eight children to cover this same cost, driving up the per-child cost of care.19

Privately operated programs are the primary provider of licensed child care in the United States, especially for infants and toddlers.20 These providers have a choice in how they set up their program and in the age groups they choose to serve. They may not serve infants and toddlers if they cannot generate sufficient revenue to cover their costs. Most programs that successfully serve infants and toddlers cross-subsidize revenue from preschool classrooms in order to support younger classrooms. Unfortunately, the true cost of providing high-quality infant and toddler care—with adequate compensation for teachers—is far higher than most working families can afford.21

At the same time, public funding for infant and toddler child care is severely limited and lags far behind public funding for preschool. Only a small fraction of eligible families actually receive child care assistance, and the amount that providers are reimbursed for infant and toddler care is barely enough to cover the cost of operating a program that meets basic licensing standards in most states—let alone a high-quality program.22 Therefore, providers in many neighborhoods cannot afford to take children who qualify for child care assistance and cannot find enough parents who can afford to pay tuition that covers the true cost of high-quality infant and toddler care.

As a result, many providers either opt not to serve infants and toddlers, instead focusing on older children for whom revenues can more closely cover the cost of care, or they provide care but pay their teachers inadequately. While child care teachers earn an average of just $10.72 per hour, those working with infants and toddlers make, on average, $2.00 less per hour than those working exclusively with 3- through 5-year-olds.*23 This “wage penalty” dissuades qualified infant and toddler teachers from entering and staying in the field and exacerbates economic stress for those who do.24

Child care arrangements for infants and toddlers

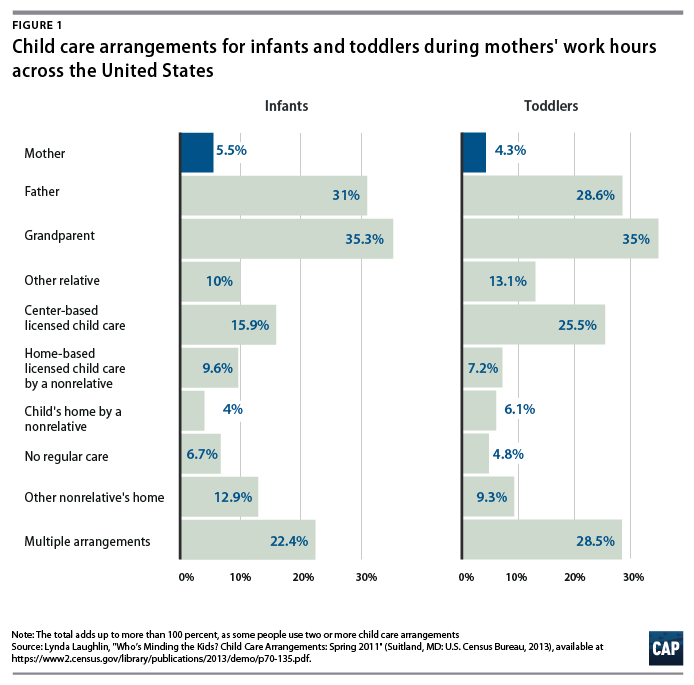

Infants and toddlers are cared for in a variety of child care settings, including centers, licensed and license-exempt homes, and their own homes. Caregivers include early educators as well as grandparents and other relatives or friends. The graph below shows the proportion of infants and toddlers who are in different types of settings while their mothers are working. Children may be in multiple regular arrangements.

This analysis examines the supply of licensed child care by county, which is only one component of access to child care. While cost and location tend to drive child care decisions for low-income parents, families may consider a number of other factors when selecting child care. Increasingly, parents with young children need child care during nontraditional hours that coincide with their work schedule. And as families become more diverse, so do their needs. Parents may prefer a child care provider who speaks their home language and shares their culture. Additionally, for parents and children with disabilities, child care programs may not be accommodating of their needs or may turn them away.25 Many families often have even fewer or no options for accessible child care once their family’s unique needs are considered.

This analysis does not include family, friend, and neighbor child care providers, who are generally exempt from licensing because they care for a number of children that is below the state’s licensing threshold. For some families, having a trusted family member or friend care for a child is a preferred choice that is mutually beneficial for the parents and the caregiver. But as fewer parents raise their children near their family of origin, informal care options may be more limited. For too many families, unlicensed or license-exempt child care is a forced choice when other options are not available. In some cases, a family member may step in to provide child care to help a parent who cannot find another arrangement. However, this family member may do so to the detriment of their own economic security.

In this study, it is not possible to analyze the supply of family, friend, and neighbor child care. However, all families need the option of licensed child care in centers or homes to make a real choice about which arrangement is best for their child. For parents who want or need licensed child care, an unregulated setting can be fraught with worry given the significant variations in quality across unlicensed providers.

The supply of infant and toddler child care in nine states and the District of Columbia

While, anecdotally, many parents know that infant and toddler child care supply is limited, very few studies have analyzed supply and demand for young children specifically. To begin to quantify the problem, the Center for American Progress obtained data on infant and toddler child care availability from nine states—Indiana, Maryland, Mississippi, Montana, North Carolina, Ohio, Oregon, Vermont, and West Virginia—and the District of Columbia. Unfortunately, few states have publicly available data on child care capacity or enrollment by age group, making it difficult to conduct a nationwide analysis of infant and toddler care supply. Nonetheless, these nine states and the District of Columbia cover a diverse portion of the country and provide a window into trends that may occur nationwide.

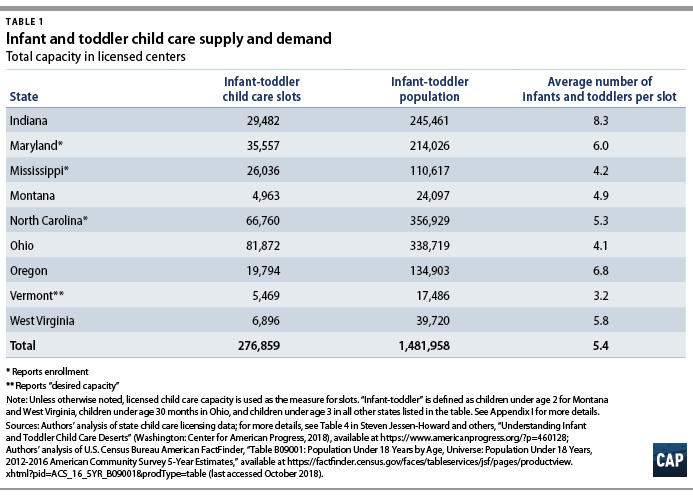

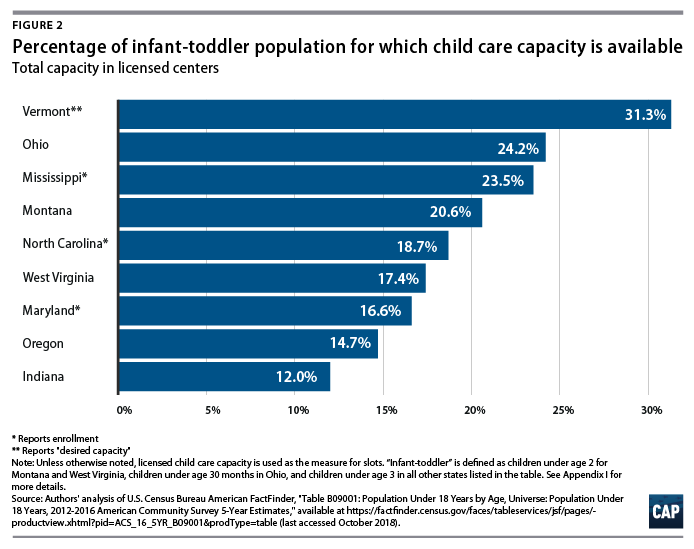

Across each of the nine states, this analysis found that the number of children under age 3 far exceeds the number of child care slots available for infants and toddlers. On average, there are more than five children under age 3 for every licensed infant and toddler child care slot. The deficit for this group is more than three times greater than it is for preschoolers, as there is one slot for every 1.7 3- through 5-year-olds. The problem is particularly pronounced in Indiana, Maryland, and Oregon. (see Table 1)

In rural areas, the supply of licensed infant-toddler child care is especially low relative to the population of children under 3. This analysis found that the more rural the county, the lower the supply of infant and toddler care. Counties are coded by the U.S. Census Bureau as “mostly urban,” “mostly rural,” or “completely rural.”26 In counties that are considered completely rural, there are about 10 infants and toddlers for every licensed child care slot. In addition, there are 19 counties—all of which are mostly or completely rural—across six states that have no licensed child care capacity for infants and toddlers. Of the 547 counties included in this analysis, just 20 have a licensed child care slot for every three children under 3.

Not surprisingly, lower-income areas had the lowest supply of licensed infant and toddler child care. Counties with a median family income in the bottom 20 percent of all counties in that state have about seven infants and toddlers per slot. In contrast, there are five infants and toddlers per slot in the top 40 percent of counties across these nine states. This is no accident; private child care programs are more likely to set up business in areas where residents can afford to pay for care than to rely on insufficient child care subsidies. This exacerbates the problems that low-income families face in finding care. Not only is the price of care prohibitive, but child care providers are also scarcer in these communities.

Infant and toddler child care supply by setting

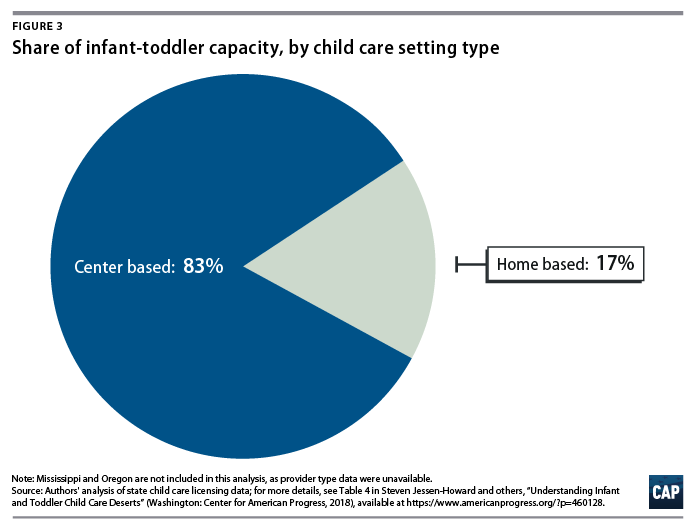

The majority of licensed child care capacity in the United States is found in child care centers. While there are significantly more family child care providers across the country than child care centers, the difference in program size means that centers enroll a larger proportion of children under the age of 6. Nearly 80 percent of child care centers enroll more than 25 children, whereas in most states, family child care providers are licensed to serve between six and eight young children.27 Unfortunately, many centers choose not to serve younger children because they are costly to enroll. The data from these nine states are aligned with this national picture, with the vast majority of infant and toddler care slots in this sample found in child care centers.28 (see Figure 3)

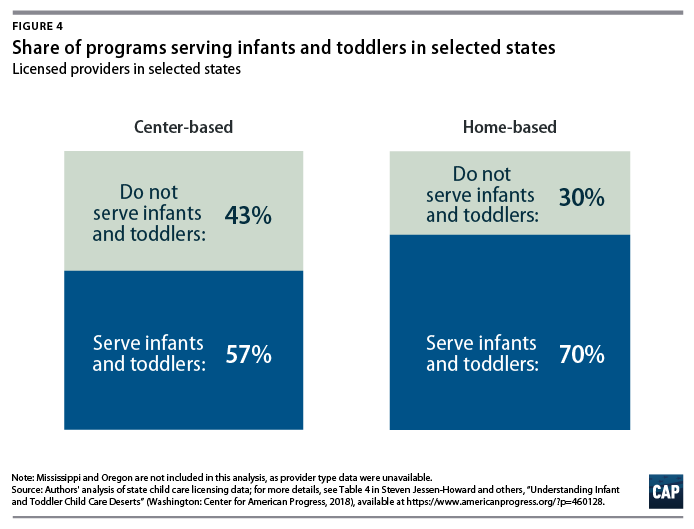

While 83 percent of total infant and toddler capacity in these states is found in child care centers, these programs are less likely to enroll infants and toddlers than family-based providers.29 As shown in Figure 4, around 57 percent of licensed child care centers serve the infant-toddler population, compared with 70 percent of family child care providers. These numbers include all providers that serve any children under the age of 3 and would likely be lower for the youngest children.30

The supply of infant and toddler care in Washington, D.C.

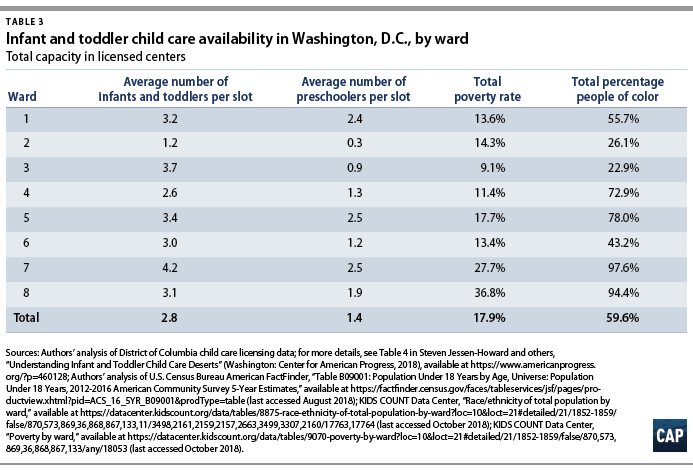

The District of Columbia is included separately from the state analysis, as it is only one county and is more comparable to the child care landscape in other cities rather than states. Nonetheless, its eight wards make it possible to examine the inequities of child care supply existing within the district. In total, there are just under three infants and toddlers for each infant and toddler child care slot—twice the ratio of preschoolers for each child care slot. While this gap is smaller than that of any state examined, child care is in especially high demand in Washington, where 75 percent of young children have all available parents in the workforce.31

Analysis of the district sheds light on inequities within licensed child care supply. Wards 5, 7, and 8 have the highest levels of poverty and also reflect some of the largest gaps in child care supply for young children. In addition, Ward 7 contains the highest proportion of people of color and has the largest gap between the supply of infant-toddler child care and the potential demand.

A ward-by-ward analysis also reveals child care preferences that complicate a geography-based supply and demand analysis of child care availability. From the ratio data alone, it appears that Ward 2 has an excess of preschool capacity and could provide child care for nearly every infant and toddler. A likely explanation is that Ward 2 contains the highest concentration of office spaces, and many individuals prefer a child care provider closer to their place of work, not necessarily closer to their home. In addition, a significant population commutes into Washington from neighboring regions of Virginia and Maryland.32 While this group likely occupies a meaningful portion of the district’s child care slots, they are not reflected in the district population, meaning the supply problem is likely worse than indicated by the child to child care slot ratio across the district. Further complicating things, Washington has a high concentration of federal government employees, some of whom can enroll in on-site child care at their offices.33 Therefore, many of these slots, especially in Ward 2, are not available for most families, and many of the children who fill them do not reside within the ward.

Washington has taken important steps to expand access to early childhood education over the past decade through its universal preschool initiative. However, the district provides an important example of the need to consider the impact on care for younger children when expanding preschool. While free, universal preschool has increased access to early education and improved the maternal labor force participation rate, subsidizing care for older children exacerbated the gap in available revenues for providers who care for 0- to 2-year-olds compared with those who care for 3- to 4-year-olds.34 This makes it more profitable to care for older children.

The Council of the District of Columbia recently approved “Birth to Three For All DC” legislation.35 If fully funded, this bill would expand subsidies to reimburse providers for the true cost of providing care, cap family payments at 10 percent of family income, and invest in child health and family supports through programs such as home visiting.36 This program, combined with Washington’s existing universal preschool program, would constitute the most comprehensive child care program in the United States and could be a model upon which states and cities could base their child care policies.

The consequences of infant-toddler child care deserts

The shortage of licensed child care has significant impacts on children and their families. When working families cannot find licensed child care, they may leave the workforce altogether or rely on a patchwork of arrangements in unlicensed programs or through extended family members, friends, or neighbors. For parents fortunate to live close to trusted connections, this type of care arrangement can be relatively cheap and convenient. Nonetheless, informal care arrangements lack the safeguards and quality standards that protect children in licensed care. In informal settings, children are less likely to receive the supervision and attention they would receive under the mandated ratios of licensed care, and caregivers are less likely to have received training on caring for young children.37

The experiences children have in their first three years of life are critically important; infants and toddlers form more than a million neural connections every second.38 The cognitive, emotional, and social capabilities children develop in their earliest years lay important groundwork for their future success. Nonparental caregivers can have a significant impact on this development. Therefore, it is critical that infants and toddlers have access to the best possible care and that their needs are not dismissed as merely baby-sitting.

Availability of child care is also essential for the families of infants and toddlers. The first years of a child’s life are a particularly difficult time for families. Caring for an infant requires a massive investment of time, energy, and money. Given the price of raising a child, many parents cannot afford to take significant time off or leave the workforce, and the United States is the only developed country not to offer paid parental leave.39 Furthermore, the high price of child care adds to the stress on parents of young children. A typical family with an infant and a toddler would have to pay more than $20,000 per year for child care, which adds up to almost 30 percent of the median income for families with children in the United States—more than four times the 7 percent benchmark that the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services deems to be affordable child care.40

If neither formal nor informal care is available, parents—most often mothers—are forced to take time off work or leave the workforce entirely to care for their children. Nearly two-thirds of parents of children under 18 stated that their career or career prospects had been negatively affected because of child care considerations.41 This results in major economic penalties for young families. The typical decrease in income associated with having a young child is nearly $15,000, equivalent to about 14 percent of income for the average two-adult household, controlling for other factors.42 For single mothers, the loss of earnings is even greater.

Furthermore, parents that take off work lose more than just short-term wages. Factoring in lost wage growth and retirement benefits, a 28-year-old woman making the median salary for women in her age bracket would lose nearly $350,000 over the course of her life by taking just three years off from work to care for a young child.43 Therefore, even if a parent had access to a suitable early learning program when their child turned 3, they would still have sacrificed nearly 10 times their current salary by leaving the workforce to care for their child from ages 0 through 2.

Policy recommendations

Traditional supply and demand economics would suggest that the undersupply of infant and toddler child care identified in this report would lead to an increase in private providers entering the market. Unfortunately, as has been discussed, the current revenue sources available to providers are insufficient to cover the cost of providing quality care, ultimately hindering the ability of the market to respond appropriately.

However, there are ways that policymakers can respond, helping increase the supply of licensed child care for infants and toddlers and ensuring that working families have options when it comes to finding care for their young children.

- Improve data collection for infant and toddler child care. All states should collect and report child care enrollment data by age. As this report’s analysis demonstrates, the age of a child plays an important role in whether families will be able to find and afford care. Data that treat children under 5 as a monolithic group cannot identify and address the unique needs of infants and toddlers.

- Increase public investment in child care for infants and toddlers to reflect the cost of providing care. It is incredibly costly to provide care for infants and toddlers because of the high staffing levels needed to meet their supervision needs. Infant and toddler caregivers are already severely underpaid, yet most families still cannot afford to pay child care prices. To create lasting supply, public investment needs to change the equation by expanding subsidies so that families can afford infant and toddler care and by raising provider reimbursement rates so that caregivers can afford to provide it. These public investments must consider the diverse needs of families and focus on building supply for families whose needs may not be met by the existing child care market. This is especially true for parents who work nontraditional hours, families in rural areas, and parents and children with disabilities. New investments must recognize that meeting the diverse needs of families may come at a higher cost.

- Think beyond preschool. In many states, public preschool has been expanded in recent years, providing important benefits for 4-year-olds and their families. However, there have been few examples of the same investment being made in younger children. It is important to ensure that affordable child care options are available to families of infants and toddlers as well. Waiting until preschool to support early learning programs misses the opportunity to help children during the most important years of their development and to support parents when they are most vulnerable financially. In addition, states should consider the collateral impact of increasing investment in preschool without doing the same for young children. When older children are moved out of child care programs and into public schools, it becomes more difficult for child care programs to remain financially sustainable without older children to offset the costs of younger children.

- Provide paid family and medical leave. Another policy that supports care for young children is comprehensive paid family and medical leave for new caregivers. Currently, the United States is the only developed economy that does not guarantee any paid leave to parents.44 Allowing caregivers time to care for their children provides multifaceted benefits and ensures that children have a healthy start in life.45 Parents could spend valuable time with their infants and build family bonds. Additionally, research has shown that when fathers and nonbirth parents take paid family leave, they become more engaged in the care of their child, which improves children’s development, family well-being, and the equal division of caregiving in the household.46 Paid family leave would also reduce the demand for child care during the portion of the time in which it is the most difficult to find and expensive to provide.

- Implement a comprehensive solution to support the early childhood education system. While investments specific to infant and toddlers are long overdue, a comprehensive approach is needed to adequately fund the entire early childhood education system. Recent funding increases for the Child Care and Development Block Grant (CCDBG) have helped states shrink waitlists for child care assistance; raise provider reimbursement rates; and take further steps to improve the supply, quality, and affordability of child care.47 This increased investment is a step in the right direction, but more is needed to enact a comprehensive solution that ensures that affordable, high-quality care is available for all children—infants and toddlers included. The Child Care for Working Families Act is one proposed solution that would cap the amount families pay for child care at 7 percent of their annual income, limiting what the average family would pay to a maximum of $45 a week.48 The bill would also improve child care quality standards and increase pay for early childhood teachers. This type of comprehensive approach would address the integrated needs of supply, quality, and affordability for children of all ages.

- Invest in child care infrastructure. Just as policymakers from both political parties support investing in roads and bridges to promote economic growth, the United States needs to prioritize investments in child care infrastructure. Before any parent can engage in economic activity, they need reliable, affordable, and safe child care. Building a child care infrastructure means updating child care facilities, including centers and family child care homes; supporting licensing and monitoring systems; and preparing the early childhood workforce to expand the number of qualified early educators.49 To address child care deserts specifically, states can establish incentives to support child care businesses expand or enter new markets, offering tax credits or start-up grants targeted to the areas of highest need.

Conclusion

The data in this report show that Benton County is not alone in its lack of licensed child care for infants and toddlers. The fact that the states in this sample only have enough capacity for 1 in every 5 infants and toddlers highlights that child care supply in the United States fails to meet the needs of working parents, especially those with the youngest children. While there has been an increased recognition of the importance of preschool and subsequent investment, the same support and investment for infant and toddler care have lagged. The data in this report have shown that families around the country—especially those in lower-income and rural areas—are left with few child care options for their youngest children. Families are then forced to make career sacrifices that affect their economic security or to weave together a patchwork of care that may not fully meet their family’s needs.

Given the critical importance of the first years of life, it is crucial that federal and state elected officials focus on the needs of infants and toddlers. First and foremost, this should include increasing current child care investments to match the higher cost of providing care for infants and toddlers. Furthermore, policymakers should implement a comprehensive solution that ensures that working families can afford licensed child care, addresses the underpaid child care workforce, expands child care infrastructure, and guarantees that families can take the time they need to be with their newborns. Every family should be able to access affordable licensed child care, regardless of the county they live in or the age of their child.

About the authors

Steven Jessen-Howard is a research assistant for Early Childhood Policy at the Center for American Progress.

Rasheed Mailk is a senior policy analyst for Early Childhood Policy at the Center.

Simon Workman is the associate director of Early Childhood Policy at the Center.

Katie Hamm is the vice president of Early Childhood Policy at the Center.

*Correction, October 31, 2018: This report has been updated to clarify the difference in hourly wage between child care teachers working with different age groups

Appendix I: Methodology, data sources, and limitations

In each state, any child care provider that regularly cares for more than four or five nonrelative children is required to have a license. Different states have different requirements for licensing, with some states only asking that child care providers register their locations and hours of operation with the state so that they can be inspected for safety regulations. Because certain safety regulations may apply differently to different age groups of children, most states ask providers about the age groups that they accept into their care. A smaller group of states differentiate how many children may be enrolled within each age group, depending on staffing levels, physical space limitations, or other factors. This is commonly referred to as “licensed capacity” and forms the basis of this analysis.

The authors reviewed child care licensing data from every state and the District of Columbia, finding nine states for which the data included the licensed capacity for just infants and toddlers. This study defines infants and toddlers as children under 36 months of age. In a few cases, inconsistency in the data required the authors to use a different age cutoff. Ohio’s licensing data include capacity for children less than 30 months old, and both Montana and West Virginia include capacity for children less than 25 months old.

This measure of infant and toddler capacity for each provider was then aggregated by county. The overall capacity of the infant and toddler child care market in each county was then compared with the most recent U.S. Census Bureau estimates of the population under the age of 3 in these counties. In the states with slightly different infant and toddler licensing ages—West Virginia, Montana, and Ohio—the estimated infant and toddler population was adjusted to match the age range used for child care licensing. For example, because Montana defines infants and toddlers as children under 25 months of age, the population estimate for Montana counties was reduced by one-third to estimate the number of children in that age range. This adjustment allowed the supply-demand analysis to remain consistent across states.

Measuring capacity for only infants and toddlers in centers that serve a variety of ages can also be imprecise. In the state of Indiana, centers self-reported capacity by age range, creating some instances in which the range included infants and toddlers as well as children older than 3. In these cases, the authors made inferences about the proportion of attendees who were less than 3 years old, which may differ somewhat from actual enrollment.

It is important to note that licensed capacity is an imperfect measure of the available supply of child care. It is often determined by formulas involving the physical area of a center and the staff size. As a result, some centers are licensed for capacities far surpassing what they intend to open for enrollment. In the case of Vermont, the authors were able to use “desired capacity,” which is defined as “the number of slots a provider reported offering for a given age group.”50 In Maryland, Mississippi, and North Carolina, the authors use actual enrollment data. While these measures are likely more reflective of the number of potentially available child care slots at each facility, they could result in these states appearing to have lower capacity than states that use licensed capacity. Comparisons across states are therefore less reliable when they use different measures of licensed child care capacity.

Finally, the county-level estimates of supply and demand for infant and toddler child care were combined with U.S. Census Bureau rural designations, as well as census estimates of each county’s median family income.

Appendix II: County-specific results