Attending college as a parent can be a daunting affair: It’s hard to find enough hours in the day for work, family, and school. Many institutions do not offer any child care and classes may only be available at inconvenient times. For many student-parents these stresses are too much to handle; only one-third of undergraduate parents finish a credential within six years of enrolling.

Now, new data show another challenge for student-parents: repaying their federal loans. The analyses presented here show that almost half of student-parents who began college in the 2003-04 school year and borrowed a federal loan for their undergraduate education defaulted within 12 years of enrolling. That’s double the rate of borrowers without children.

Even worse, 70 percent of student-parents who defaulted were single. For African Americans, single parents made up 90 percent of student-parent defaulters. As a result, 1 in 10 undergraduate borrowers was a single parent, but these students represented 2 out of every 5 undergraduate defaulters. For these borrowers, who are often the sole providers for the family, default can keep them entrenched in their current financial situations, making it all the more difficult to improve their circumstances.

Student-parents are not a small subset of higher education enrollment. There are about 4.8 million undergraduates who are parents, 2.7 million of whom borrow to cover the costs of school. Students with children are disproportionately women of color, and most are enrolled at community and for-profit colleges. When these students borrow and default, they are thrust into a financial situation that is difficult to remedy.

Combined with low completion rates, these figures demonstrate how much our higher education system struggles to serve those who need extra assistance. When student-parents don’t have access to comprehensive support systems, they suffer, both while enrolled and after. The federal government, states, and institutions must find ways to better address the needs of student-parents if the goal is to give them the opportunity to provide a better future for themselves and their families.

The consequences of default

Borrowers who default on their loans see their credit scores plummet, making it harder to take on additional debt, to rent or purchase a home, or to even get a job. The federal government can garnish wages and tax returns of defaulted borrowers, even if they are low-income. Defaulted borrowers also lose access to additional federal financial aid, which can compromise their ability to re-enroll in school. This is a big problem for student-parents who default, 54 percent of whom did not earn a credential. These consequences can compromise the ability of student-parents, particularly those who are single, to provide adequate resources and opportunities for their families.

Lower default rates would allow more student-parents to experience the potential socioeconomic returns of a college education. Fewer defaults would also benefit the nation as a whole. Taxpayer dollars could be diverted to student outreach instead of being spent attempting to collect defaulted loans. Americans could also have confidence that our student loan system is built to serve students, even when they face difficult odds.

Almost half of student-parents default on their loans

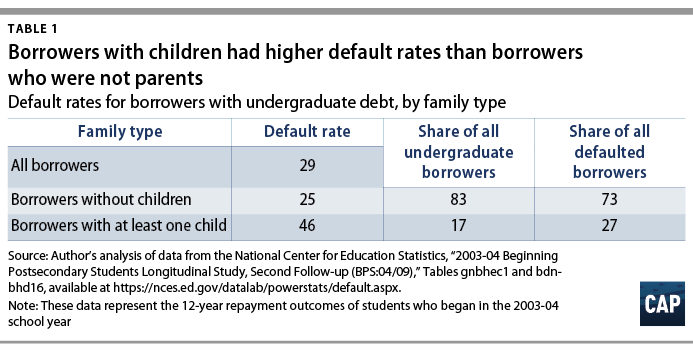

Nearly half of students with children who entered college in 2004—46 percent—defaulted on their federal loans within 12 years. That’s 1.5 times the rate of all undergraduates and almost twice the rate of borrowers without children. As a result, students with children were only 17 percent of undergraduate borrowers but represented 27 percent of all undergraduate loan defaults

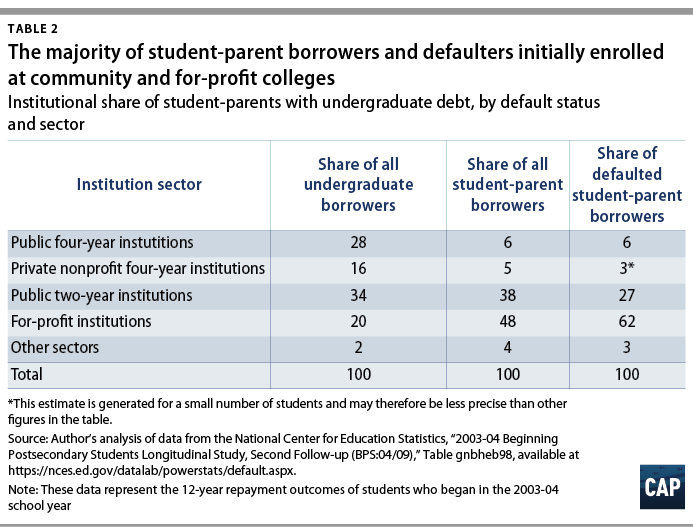

Even though for-profit colleges enrolled 20 percent of all undergraduate borrowers, 60 percent of student-parents who defaulted started at these institutions. In fact, 44 percent of for-profit defaulters were parents, the highest share of any sector. That’s double the share of community colleges and 10 times the share of public, four-year institutions. These data fall in line with other research that shows that students who first enroll at for-profit colleges have higher default rates than other types of institutions. However, the default rates for student-parents at for-profits are disproportionately high compared to default rates for all borrowers, which could suggest that these colleges are not providing the resources student-parents need to succeed.

Default rates are even worse for parents of young children

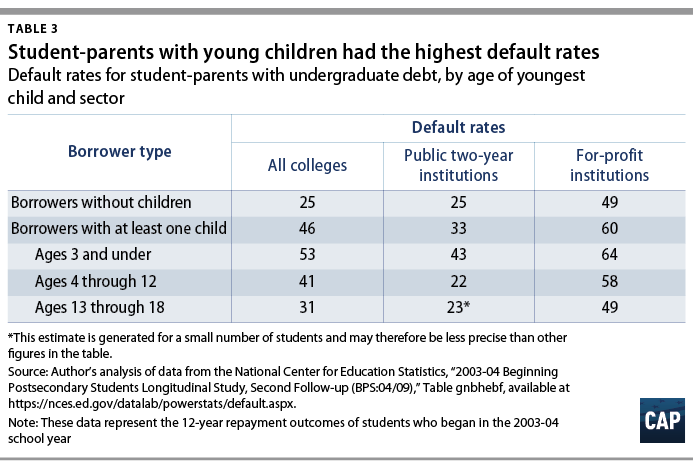

Parents of young children particularly struggled to repay their loans. Fifty-three percent of students with children age 3 or younger defaulted, compared to 31 percent of parents with teenagers. This is perhaps because students with older children have fewer child care costs and obligations, which allows them to devote more time and resources to school.

Again, students who enrolled at for-profit colleges had the worst outcomes. At these colleges, sixty-four percent of student-parents with young children defaulted on their loans within 12 years of enrolling. As a result, one-quarter of all undergraduate defaulters at for-profits had children age 3 or younger.

The plight of single parents

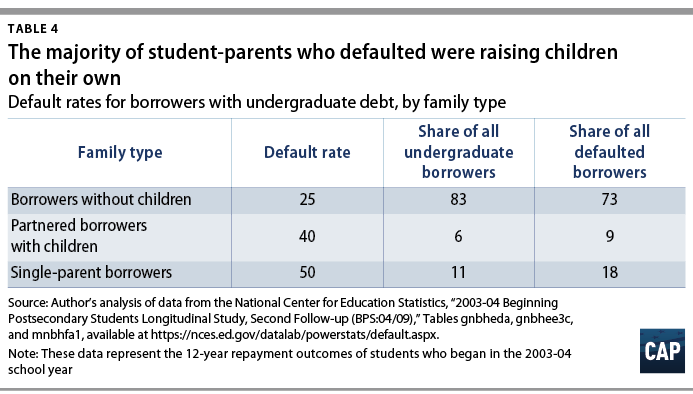

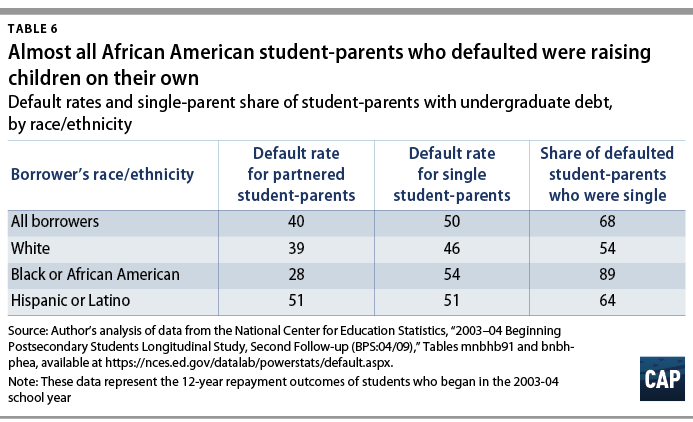

Perhaps most troubling is how many defaulted borrowers were single parents. Single parents make up two-thirds of student-parents who default, and account for 18 percent of all undergraduate defaults.

High rates of default have important implications for these families. When students who have partners default, they are often able to lean on the credit and finances of the other parent to make ends meet as the former student resolves the default. However, for single parents, there may not be another adult who can support the family. This can keep single-parent families in dire economic circumstances for a much longer period, if they are ever able to get out.

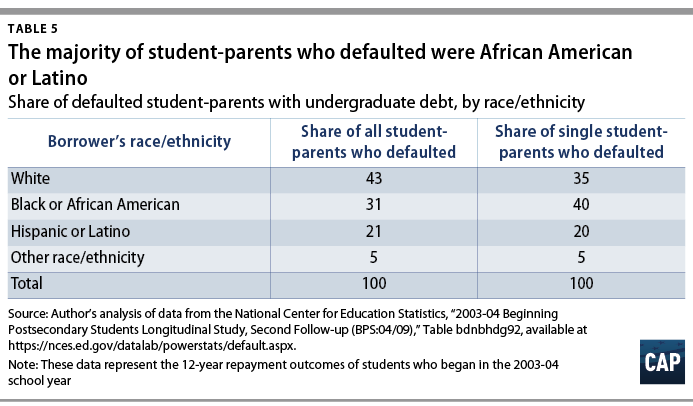

African Americans and Latinos make up 60 percent of defaulted single parents

Undergraduates of color are more likely to have children than their white counterparts, and the data show that they are also a larger proportion of student-parents who default. African Americans and Latinos made up 52 percent of all student-parents (and 60 percent of all single parents) who defaulted within 12 years of enrolling.

The default issue is particularly acute for single African American student-parents. Almost 90 percent of defaulted African American students with children were single. That share was 64 percent for Latino student-parents, 10 percentage points higher than for white student-parents.

These data provide further evidence that single parents, especially those of color, should be a primary group of concern. CAP recently revealed the extent to which African American borrowers struggle to repay their student loans, and the analyses presented here provide further evidence that underrepresented students experience particularly poor outcomes. To confront these problems, the Department of Education must collect data on borrowers’ race to better understand these problems and develop effective solutions.

What can be done to help borrowers with children?

Parents who go to school seeking a better life for themselves and their children deserve better odds than a coin flip that they might default on their loans. The data show that the size of the loan balances of students with children are not the problem. Quite the opposite. Across all types of colleges, student-parents who defaulted had smaller balances than those who did not. This holds true for single parents as well as students who are raising children with a partner.

Why are student-parents defaulting at such high rates? It is difficult to say without additional data, but the federal government, states, and institutions can take several steps to improve the educational experiences of these students, which can help keep them complete college and improve their repayment outcomes.

On the repayment side, the federal government should examine whether student-parents are able to take advantage of plans that tie monthly payments to borrowers’ incomes. Unfortunately, the students included in these data enrolled six years* before Income-Based Repayment became available, which could partly explain these negative outcomes. However, more than 1 million borrowers default every year, raising questions as to whether students who would benefit from income-driven repayment options are using these plans. If they are not, the federal government should conduct additional research on default, and put together focus groups and other consumer testing to figure out why borrowers don’t use these plans.

Policymakers can also do more to keep undergraduates with children from having to take on debt in the first place. The federal government and states should extend public assistance programs, such as the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) and Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), to more adults enrolled in college to help offset the costs of student-parents. States should be more supportive of these students by guaranteeing them state grant aid and extending promise—often called free college—initiatives beyond recent high school graduates. On the institutional side, free or subsidized child care, flexible course schedules, and opportunities to earn credit by assessing students’ current knowledge and skills can help reduce student-parents’ costs and the time they spend enrolled.

If the aim of the America’s higher education system is to provide an escape from poverty and to spur the prosperity of those who have been historically marginalized, then ensuring that student-parents are able to successfully repay their debt is a must. Student-parents should be getting more from our higher education system, and policymakers have the power to improve their outcomes.

Colleen Campbell is the associate director for postsecondary education at the Center for American Progress.

*Author’s note: Although IBR was authorized in 2007, borrowers could not enroll in the plan until 2009.