Paid leave is gaining more and more attention in Congress, where members are beginning to recognize the importance of allowing workers to care for themselves and their families without sacrificing a paycheck.1 Currently, nearly 60 percent of U.S. workers have access to up to 12 weeks of leave for family or medical needs through the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA).2 For too many workers, however, this is a benefit in name only because they cannot afford to take unpaid leave.3 The United States is the only advanced economy that does not guarantee workers access to any form of paid family or medical leave. Only 17 percent of workers currently have paid family leave through their employers, and only 39 percent have short-term disability coverage.4 Low-wage and part-time workers—who are disproportionately women—are even less likely to have access to these benefits.5

As policymakers start to address the demand for a federal paid leave policy, they must pursue a comprehensive program that truly meets the needs of all workers and their families, not just a select few. Particularly, policymakers who tout the importance of children and families’ well-being must acknowledge that children are affected by their parents’ and caregivers’ access to leave. This issue brief presents new analysis by the Center for American Progress that finds that 52 percent of FMLA leaves taken by workers in 2012 occurred when they were also caring for children at home. These workers deserve comprehensive paid family and medical leave, so that they are able to spend time with their children.

Unfortunately, not all federal paid leave policy proposals address this need for comprehensive leave. Proposals that would provide paid leave for only parents of new children—after the birth of a child, the adoption of a child, or the placement of a foster child—fail to recognize that caregiving needs do not stop after the first 12 weeks of a child’s life.6 This type of narrow policy would not address the majority of working parents’ caregiving needs that occur throughout a child’s life—for example, an 8-year-old child with a serious illness such as a congenital heart defect, or a single mom recovering from a severe injury while also caring for her young children. Policymakers who promote these narrow proposals minimize the breadth and depth of families’ caregiving challenges and fail to respond to the needs of families when they experience a serious illness or injury.

For children and families to truly benefit under a paid leave policy, policymakers must ensure that workers have access to comprehensive paid family and medical leave. This issue brief explains the need for such a policy and presents new CAP analysis of FMLA data to show the myriad purposes for which workers use leave while caring for young children or elderly relatives.

Evidence of FMLA leave usage proves that workers and their families need more than new child leave

All workers and their families may, at some point in their lives, need time away from work to recover from a serious illness, care for a family member with a serious illness, or care for a new child. Providing only one type of leave—for example, paid new child leave for the birth of a child, the adoption of a child, or the placement of a foster child—excludes far too many workers and their families. It also ignores the precedent set by the FMLA, which provides comprehensive leave for eligible workers.

A 2012 survey for the U.S. Department of Labor provides significant evidence about the program’s usage.7 The technical report from the survey, which counted each worker’s most recent FMLA leave in the previous 12 months, shows that only 21 percent of workers took parental leave for a new child.8 More than three-quarters of workers who took FMLA leave used it for a different purpose: A majority, 55 percent, used it to recover from their own illness, and 18 percent used it to care for an immediate family member—a parent, spouse, or child—with a serious health condition.9

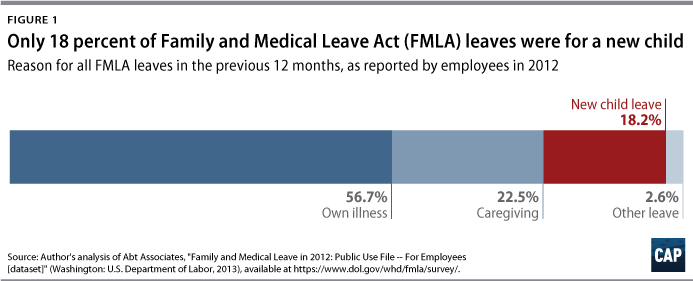

New CAP analysis of the 2012 FMLA employee survey further underlines the importance of comprehensive paid family and medical leave for families and children of all ages. This analysis calculated all qualifying FMLA leaves reported by workers in 2012 for the previous 12 months, including for workers who reported taking more than one leave in that period. Numbers used in the 2012 technical report count only one leave per worker—for example, workers’ most recent leave in 2012 for the previous 12 months. Because the author counts all leaves for every worker reported in the survey, all of the following percentages are derived from the share of all FMLA leaves taken during the aforementioned 12-month span, not the share of all workers who took FMLA leave. Using this method, the percentage of FMLA leaves used to care for a new child drops from 21 percent, as shown in the 2012 technical report, to 18.2 percent. (see Figure 1) A majority of FMLA leaves reported in the 2012 survey were used by workers to care for their own serious illness or to care for a family member with a serious illness.

Leave for workers who are parents or caregivers of young children

Many families may experience life events beyond the birth of a child, the adoption of a child, or the placement of a foster child that will cause them to need time away from work. Children are affected by their caregivers’ access to leave. They still need someone to care for them when their parents and caregivers experience a serious illness or injury, or when they are seriously ill or injured themselves. No children facing cancer, an unexpected medical procedure, or some other medical emergency should be left alone in the hospital because their family cannot afford time away from work. Workers need comprehensive paid family and medical leave so that they can care for themselves and their children without plunging into poverty and putting incredible stress on their families.

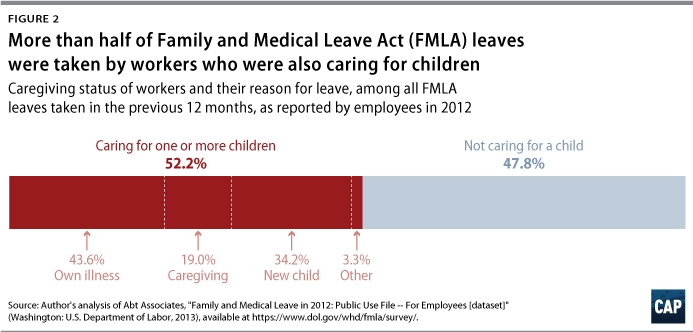

No matter workers’ reasons for taking leave, they are often responsible for caring for children during that leave. In fact, as of 2012, among all FMLA leaves that workers reported taking in the previous 12 months, more than half—52.2 percent—were taken by workers who were also caring for one or more children. (see Figure 2) These data make clear that the benefits of FMLA leave not only enable workers to keep their jobs and maintain their health insurance while taking time off, but also extend to individual workers’ children and others in the household. The majority of leaves taken by workers with children at home did not involve new child leave. Among the 52.2 percent of FMLA leaves where workers were caring for one or more children, almost two-thirds—65.8 percent—were for a reason other than new child leave. (see Figure 2) A paid new child leave policy would therefore not benefit children whose parents and caregivers needed access to other types of leaves.

Leave for workers to care for seriously ill children

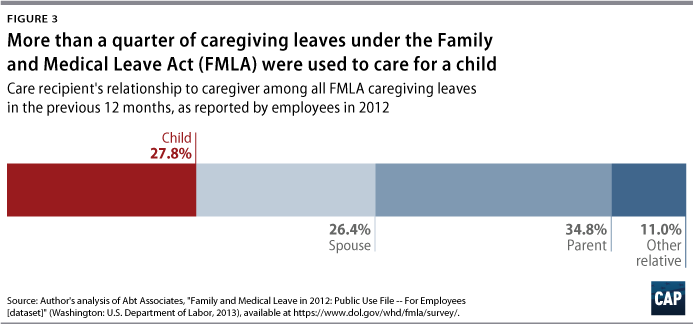

Workers also use FMLA caregiving leave to care for children with serious illnesses or injuries, such as epilepsy. These children deserve to be cared for by their families and to spend time with their loved ones without their parents having to worry about the next paycheck or keeping a job. Further analysis of the FMLA 2012 employee survey found that among the 22.5 percent of FMLA caregiving leaves taken by workers to care for a parent, spouse, or child in the previous 12 months, more than a quarter—27.8 percent—were used to care for a seriously ill child. (see Figures 1 and 3) During this same time frame, most FMLA caregiving leaves for children were for those under the age of 18; although more than 1 in 6—17.8 percent—of these child caregiving leaves were to care for an adult child between the ages of 18 and 40. Female workers assume the majority of caregiving responsibilities, with women taking almost two-thirds—61.7 percent—of caregiving leaves for a child in the previous 12 months, as reported in 2012. Yet these workers would not be able to care for seriously ill children under a paid new child leave policy. Only a comprehensive paid family and medical leave policy would ensure that children can be cared for when they have serious illnesses or injuries, or when their parent or caregiver has a serious medical condition.

Leave for workers to care for elderly relatives

In addition to caring for children, workers also need time away from work to care for elderly family members, who are more likely to have health conditions, including chronic conditions, that need care.10 CAP’s analysis of the 2012 FMLA employee survey found that almost a third, 30.5 percent, of FMLA caregiving leaves that workers reported taking in the previous 12 months were to care for a family member age 70 years or older. Furthermore, among the one-third of FMLA caregiving leaves used to care for a parent in this time frame, more than three-quarters—76.0 percent—were for a parent age 70 years or older. This need for elder care will only grow with the rapidly aging population and the shortage of caregivers in the United States.11 Yet under a paid new child leave policy, these workers would not have access to paid leave to care for their aging loved ones.

A policy for comprehensive paid family and medical leave

In contrast to overly narrow proposals from President Donald Trump and conservative members of Congress that would only provide paid leave for those with new children, a more comprehensive proposal already exists. The Family and Medical Leave Insurance (FAMILY) Act reintroduced by Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand (D-NY) and Rep. Rosa DeLauro (D-CT) in February 2019 would provide workers access to comprehensive paid leave in order to recover from a serious health condition, to care for a family member with a serious illness, and to care for a new child.12 The proposal is modeled after similar successful state programs implemented in California, New Jersey, Rhode Island, and New York that use a social insurance system to provide workers with comprehensive paid family and medical leave.13 Comparable models have also passed in the District of Columbia, Washington, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Oregon, which are launching in the next few years.14

Conclusion

Workers’ use of FMLA leave shows that they need leave for a variety of reasons—especially for when they are also responsible for caring for young children or elderly relatives. As paid leave proposals move forward, policymakers have an opportunity to get this issue right and help millions of children and families by ensuring that proposals account for the many reasons why workers need time away from work. Getting paid leave wrong—by creating and supporting a narrow proposal focused solely on paid new child leave—will harm both children and their families. Only a comprehensive paid family and medical leave proposal, such as the FAMILY Act, will provide a real solution for workers, children, and families.

Diana Boesch is a research assistant for women’s economic security for the Women’s Initiative at the Center for American Progress.