Introduction and summary

International justice stands at a crucial crossroads, and as the 20th anniversary of the founding of the International Criminal Court (ICC) nears, there has never been a better time to take stock of the progress and challenges facing international justice. At its core, international justice is a recognition that sovereignty is not an absolute, and that some crimes—particularly genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity—are so profound that they must be prosecuted at an international level, particularly if a country where such crimes are committed lacks either the capability or the will to give such charges a fair hearing.

This report examines the relative track record of these international mechanisms to date, explores some of the challenges laid bare by their operations, and suggests some important paths forward in a deeply uncertain international political climate. The bottom line: Without robust support from international civil society and a steady effort to further professionalize these international justice mechanisms, the very real progress achieved over the past two decades is at considerable risk.

The first major use of an international criminal justice mechanism was the Nuremberg trials of Nazi war criminals following the end of World War II. More recently, over the past 25 years, international criminal justice—that is to say, the use of courts and investigative agencies staffed wholly or in part by international civil servants to try serious crimes—has evolved from an aspiration of human rights advocates to an important feature of the international landscape.

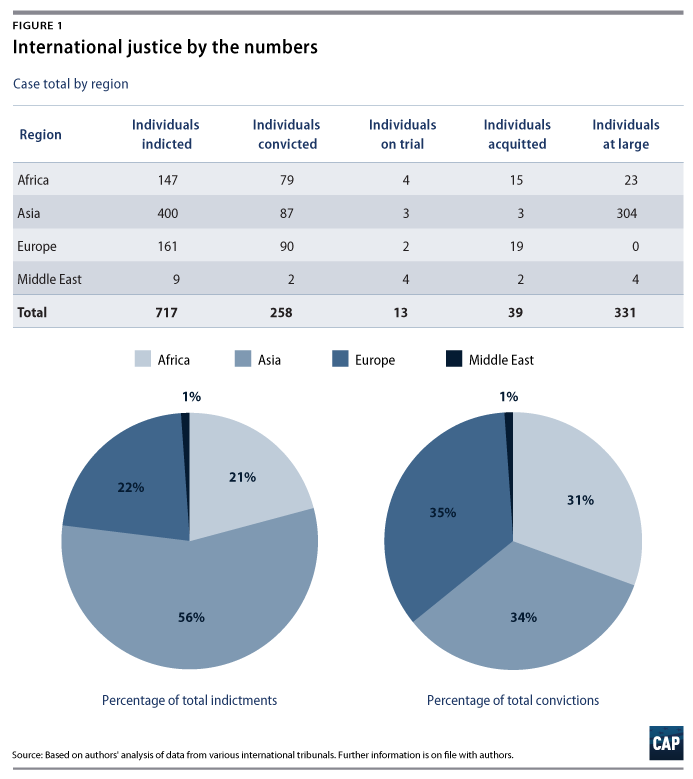

Beginning in 1993 with the creation of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), the United Nations has established tribunals with jurisdiction over war crimes and other human rights abuses committed in Bosnia, Croatia, Rwanda, Liberia, Sierra Leone, Lebanon, Cambodia, and East Timor. Along with the ICC—whose jurisdiction has been accepted by more than half the world’s nations, though the United States notably is not among the signatories—these bodies have collectively investigated more than 300 cases, indicted more than 700 individuals, and obtained more than 250 convictions.1 Alongside these entities, a number of transnational courts and investigatory bodies now operate with the authority and support of regional political institutions—for example, the hybrid Senegalese-African Union tribunal that heard the case of deposed Chadian dictator Hissène Habré in 2017.2

In many ways, the evolution of international justice has been remarkably rapid during the past two-and-a-half decades, but it is also clear that this evolution has been highly uneven, often deeply controversial, and not entirely impartial in its application. There has been a considerable backlash against international justice mechanisms, particularly among African heads of state, who argue that they have been disproportionately targeted for prosecutions. Moreover, the ICC and the array of different tribunals have widely varied in their levels of professionalism and speed. These considerable growing pains are now coupled with the ascendency of U.S. President Donald Trump, who leads an administration eager to erode a broad array of many accepted international norms and practices. And then there are the very active pushes by the likes of President Vladimir Putin of Russia, President Rodrigo Duterte of the Philippines, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan of Turkey, and President Xi Jinping of China to bend the rule of law to their own autocratic benefit.

Perhaps no moment symbolically captures the complicated legacy of the international justice system more than the November 2017 courtroom suicide by Bosnian Croat general Slobodan Praljak moments after judges at the ICTY upheld his conviction for crimes against humanity.3 Praljak’s dramatic suicide overshadowed the ruling of the tribunal and the opportunity to highlight the rendering of justice at the conclusion of 24 years of investigations and prosecutions, shifting the media’s focus to the recriminations and hard questions of the court’s critics.

The data examined in this report suggest several important trends in international justice. When it comes to enforcement, there has always been a great deal of handwringing that international justice lacks an enforcement mechanism for apprehending alleged war criminals. However, the apprehension and conviction rate of those charged with genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity is notable. Of the total investigations examined here, 717 individuals have been indicted. Of those indicted, 258 have been convicted, a conviction rate of 36 percent. These convictions include many notable big fish whom commentators were often skeptical would ever see the inside of a court room, much less be convicted. The list of those indicted includes Liberian President Charles Taylor, Bosnian Serb general Ratko Mladić, Congolese Vice President Jean-Pierre Bemba, Chadian President Habré, and former Yugoslav President Slobodan Milošević, who died while awaiting his trial in The Hague.4 And while to date, the ICC caseload has focused a good deal of attention on atrocities in Africa, the track record of the various international courts and tribunals examined, taken collectively, paint a picture of much greater regional diversity, with 35 percent of convictions coming from Europe, 34 percent coming from Asia, 31 percent coming from Africa, and 1 percent coming from the Middle East. The Middle East number will surely grow substantially in the future if justice is achieved for the atrocities committed in the ongoing Syrian conflict.

Syria itself poses a fundamental challenge to the credibility of these justice mechanisms moving forward. Battlefield atrocities and blatant attacks against civilians have been widespread. Syrian government forces, supported by Russian forces, have engaged in egregious attack after egregious attack, such as the frequent targeting of hospitals and continued use of chemical weapons. Moving justice forward in Syria, despite the severe difficulties in doing so, will be a clear benchmark for the effectiveness of international justice.

In examining the record of these respective tribunals, it is also clear that the wheels of justice have often turned slowly, in part because of the extreme intransigence of defendants and in part because of numerous operational and bureaucratic hurdles. In addition to being time-consuming, the more effective tribunals have not been inexpensive, nor should they be if they are to operate at a high professional standard. To operate at this level, courts need sufficient funding not only to pay for professional staff salaries but also to pay for intensive investigations—which often take place in difficult-to-reach and at times hostile locations—including travel, translation services, legal aid for defendants, office space rentals, witness protection, and more.

The relative competency and impartiality of these tribunals have varied greatly, and their composition and staffing represent an interesting mix of models, with some proving far more effective than others. In short, a review of tribunals and their track records suggest an international system that is learning on the fly, albeit with some real stumbles along the way. That said, these courts have had a real demonstration effect, and perpetrators are more aware than ever that they could be held responsible for their actions, even if it may take considerable time for such accounting to occur—which is a historic step forward.

It is also unsurprising that the positive trend toward accountability for the commission of heinous crimes has at times brought real political pushback and backlash. Most individuals would prefer not to be held accountable for their negative actions, and attacks against the legitimacy of these courts and tribunals are often the most expedient way to avoid justice.

Lastly, it has also become apparent that the Trump administration’s disdain for international norms and its willingness to erode the rule of law both at home and abroad represent a serious threat to a positive arc for international justice in the near and immediate terms. It will be far more difficult for international justice to progress if the United States is not only overtly hostile to the International Criminal Court but is also led by a president who is willing to look past profound human rights abuses around the globe while attacking the foundations of justice and law enforcement in his own country. Such behavior will also have its own demonstration effect around the globe, and it will be a deeply deleterious one.

A patchwork of courts

The number of transnational criminal courts active today is a reflection of the international community’s sustained commitment to the principle of accountability for war crimes and other grave human rights abuses. It also illustrates the still rather ad hoc nature used to determine what justice mechanisms should apply in any given circumstance.

The United States, at least up until the current administration, has in some ways been a strong advocate for international criminal justice, providing financial support to many transnational criminal courts, both through U.N. member contributions and voluntary donations to specific institutions. In addition, the Obama administration participated in the International Criminal Court as an observer and pledged to cooperate with the body despite continued congressional opposition to the United States becoming a full party to the treaty establishing the ICC, known as the Rome Statute.5 As stated in the 2010 National Security Strategy, the United States believes that “the end of impunity and the promotion of justice are not just moral imperatives; they are stabilizing forces in international affairs.”6 The United States also appears to have shared DNA evidence, forensics, and case-related intelligence with the court in some instances. The fact that the United States has been one of the ICC’s most important supporters while also being its most high-profile nonsignatory is a considerable paradox.

The topline objectives of international criminal justice have made enormous strides over the past 25 years, particularly the idea that there should not be impunity for those conducting war crimes, crimes against humanity, or genocide. That said, the modalities of justice and the ability of existing institutions to deliver on their mandates and maintain a high level of legitimacy remain open questions.

The past two years have been eventful ones for transnational criminal courts, marked as they were by some important successes, some major reversals, and a number of important political and legal setbacks. On the positive side of the ledger, the ICC, the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, and the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) secured the arrest and conviction of some of the key perpetrators of organized campaigns of violence against civilians in Africa and the former Yugoslavia, including former Congolese Vice President Jean-Pierre Bemba and former Bosnian Serb Republic President Radovan Karadžić.7 Bemba’s conviction also marked the first successful prosecution of rape before the ICC and the first application of the principle of commander responsibility for the actions of subordinate officers.8 Beyond the United Nations, former Chadian President Hissène Habré’s trial in an A.U.-sanctioned court was a watershed development for regional justice efforts in Africa.9

These accomplishments, while significant, are at risk of being overshadowed by other developments that have called into question the ability of transnational criminal courts to maintain high standards of professionalism, fairness, and objectivity. Chief among these has been the growing mood of hostility toward the ICC among African governments. This hostility was exemplified by the African Union’s February 2016 endorsement of a Kenyan plan for mass withdrawal from the court in response to perceptions that it has unfairly targeted African governments10—a plan that laid the foundation for the governments of Burundi,11 South Africa,12 and Gambia13 to pass legislation to quit the institution in October 2016. This in turn generated a counter-push of African support for the court. South Africa14 and Gambia15 reversed their positions, with South Africa’s effort halted on procedural grounds by the South African High Court, though the government again announced its intentions to withdraw from the ICC as recently as December 2017.16 Gambia’s change of heart occurred after the election of President Adama Barrow, ousting the repressive regime of Yahya Jammeh, who had ruled the country for 21 years.17 Additionally, following the launch of a preliminary examination into alleged crimes against humanity in his war on drugs, President of the Philippines Rodrigo Duterte announced his intention to withdraw the country from the ICC.18

Several other incidents have added to the general atmosphere of crisis around international justice. The ICTY’s failed prosecution of alleged Bosnian war criminal Vojislav Šešelj in March 2016—a full 13 years after he turned himself over to the court—led to numerous complaints of prosecutorial blunders.19 In addition, the effective stonewalling of the prosecution of former Khmer Rouge officials by current Cambodian officials, and the ongoing failure of the ICC to obtain the arrest of Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir,20 have damaged the reputations of those institutions and highlighted the challenges that transnational criminal courts face when attempting to operate in hostile political environments.

These developments have occurred at a time when the broader landscape of international criminal justice is in transition, and a number of important tribunals have recently ended, or are near ending, their caseloads. At the end of 2015, the ICTR concluded its operations,21 and the ICTY concluded operations in December 2017.22 The Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) is likely to reach the end of its docket within the next three to five years. As these flagship institutions of international criminal justice close their doors, many voices have called for the creation of new tribunals to address more recent conflicts, primarily war crimes committed in the course of the conflicts in Syria, the Central African Republic, and South Sudan, as well as concerns regarding alleged ethnic cleansing of Rohingya in Myanmar. At the same time, the ICC has signaled a shift in direction by expanding its substantive remit beyond conventional human rights abuses to crimes of cultural destruction and, most recently, environmental crimes and forced evictions—a highly curious move given its failure to fully cement support for its core mandate.23

The international justice record to date

While a comprehensive assessment of each tribunal is outside the scope of this report, it is helpful to examine some of each courts’ major contributions to international justice, as well as some of their important challenges.

International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY)

On May 25, 1993, the U.N. Security Council adopted Resolution 827 establishing the ICTY. The court was established during the various conflicts in the Balkans in response to mass atrocities and ethnic cleansing. Headquartered in The Hague, the tribunal was mandated to prosecute “persons responsible for serious violations of international humanitarian law committed in the territory of the former Yugoslavia between 1 January 1991 and a date to be determined by the Security Council upon the restoration of peace.”24 The tribunal’s indictments addressed crimes committed from 1991 to 2001 in Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, Kosovo, and the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia.25 Total estimated deaths from the conflicts are more than 130,000, with more than 4 million people displaced.26

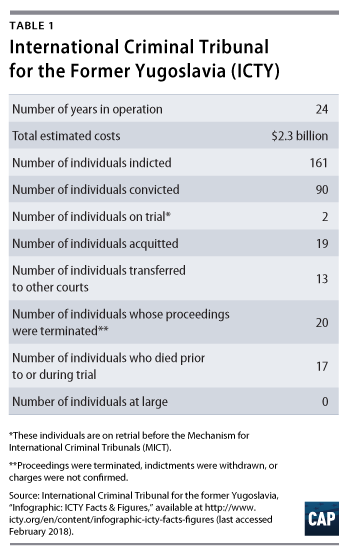

The ICTY’s creation marked the first time that the United Nations initiated a war crimes court. It is also the first international tribunal to be held since the Nuremberg and Tokyo tribunals after World War II.27 To wind down its mandate, the tribunal’s judges created a “completion strategy,” which, according to its website, centered on prosecuting and bringing to trial leaders of the most senior ranking, while referring a certain number of cases that involve intermediate and lower-ranking defendants to national courts in the former Yugoslavia.28 The strategy had originally set a 2010 completion date, but due to some late arrests—the latest occurring in 2011—the tribunal did not complete its work until December 2017, after almost a quarter century in operation.29 The total estimated costs of the tribunal were more than $2.3 billion.30

Turning first to metrics for those indicted by the tribunal, the ICTY can claim a significant victory: Of the 161 individuals indicted, none remain at large.

Of those 161 individuals:

- 90 were convicted.

- 2 are on retrial before the Mechanism for International Criminal Tribunals (MICT).31

- 19 were acquitted.

- 13 were transferred to countries in the former Yugoslavia.

- 20 had proceedings terminated or indictments withdrawn.

- 17 died prior to, or during, their trials.32

The tribunal has been criticized for not indicting a number of key players in the war, including Borisav Jović, a former Yugoslav president who appeared to implicate himself in his memoirs.33 Additionally, the tribunal has been accused of unfairly targeting Serbs for indictments—Serbs made up roughly 60 percent of those indicted. 34 However, indicted individuals also included Croats, Bosniaks, and Kosovar Albanians, and there did seem to be a deliberate attempt by prosecutors to hold parties from every ethnic group responsible for their actions during the conflict. A reasonable case can be made that Serbs faced a higher number of charges at the court because they were associated with a higher number of very serious incidents, such as the massacre at Srebrenica, where more than 7,000 Bosniak boys and men were killed by Bosnian Serb forces.35 Additionally, a special national court known as the Specialist Chambers was established in Kosovo through the European Union and Kosovo national legislation in 2015 to investigate alleged crimes between January 1, 1998, and December 31, 2000.36 Much of the court’s focus will be on alleged atrocities committed by the Kosovo Liberation Army guerillas against ethnic Serbs.37

Looking more closely at specific cases, much of the ICTY’s legacy will likely come from landmark cases that addressed brutal sexual and gender-based violence used during the conflicts. More specifically, the Duško Tadić case, in which Tadić—a former Bosnian Serb politician—was found guilty of cruel treatment and inhumane acts against detainees in Prijedor, marked the first time an international war crimes trial involved charges of sexual violence—specifically highlighting sexual violence against men.38 In the Mucić et al. case ruling, in which three of the four accused—Zdravko Mucić, Hazim Delić, and Esad Landžo—were charged with sexual violence against civilians in a prison camp in Čelebići, rape was recognized for the first time in an international tribunal as a form of torture.39 This also made rape “a grave breach of the Geneva Conventions and a violation of the laws and customs of war.”40 Additionally, this case set a legal precedent by finding a superior officer guilty of crimes committed by his subordinates.41 In its ruling on the Kunarac et al. case, in which the three accused—Bosnian Serb army officers Dragoljub Kunarac, Radomir Kovač, and Zoran Vuković—were charged with sexual violence for their “role in organising and maintaining [a] system of infamous rape camps,” the tribunal also broadened the definition of enslavement as a crime against humanity to include sexual enslavement.42 Further, all three accused in the case were found guilty of rape as a crime against humanity—a first for the ICTY and only the second time in history.43 Given the prevalence of sexual violence as a battlefield tactic, the court deserves considerable praise for addressing this thorny topic, and addressing what is very clearly a crime against humanity that has all too often gone unspoken, much less addressed.

Along with these significant achievements, however, the court also had a number of controversial rulings dealing with command responsibility. Critics have argued that the determinations in several cases undercut international justice by making it more difficult to hold commanding officers accountable for crimes committed by subordinates while under their watch.44

The first of these occurred on November 16, 2012, when the appeals court acquitted Croatian generals Ante Gotovina and Mladen Markač for crimes against humanity and war crimes committed during the 1995 Operation Storm campaign.45 U.N. military observers criticized this particular campaign for indiscriminate bombings of cities.46 According to The New York Times, court witnesses testified that following the bombings, Croatian fighters, under the overall command of Gen. Gotovina, and others “went on a rampage of looting and burning of homes and livestock, and poisoned wells to make sure that Serbs would not return.”47 By overturning the convictions, the tribunal essentially ruled that neither general was in control of the rampaging forces, thereby removing their responsibility for the actions of those under their command.48 The campaign effectively depopulated the Krajina region of almost all its ethnic Serb population, making it overwhelmingly ethnic Croat in composition.

Then, on February 28, 2013, the appeals court acquitted Gen. Momčilo Perišić, the former Yugoslav army chief and aid to Slobodan Milošević, for crimes against humanity and war crimes.49 Gen. Perišić, known to have played a critical role during the 1992–1995 war, was previously found guilty of aiding and abetting crimes against humanity and war crimes in the Bosnian towns of Sarajevo and Srebrenica and for failing, as a superior, to punish similar crimes committed in the Croatian capital of Zagreb.50 According to the New York Times, “Records showed he regularly attended meetings of the Supreme Defense Council where Mr. Milosevic and other leaders approved sending weapons, fuel, police officers and military personnel to proxy armies fighting for the Serb cause in Bosnia and Croatia.”51 In overturning the ruling, however, the appeals judges stated that Perišić “could not be held liable as an aider and abettor” and that the court had failed to provide evidence that he had “effective control over” Serbian army forces who committed crimes.52

Finally, on May 30, 2013, the court acquitted two close aids to Milošević of war crimes.53 Former Chief of the Serbian State Security Service Jovica Stanišić and former employee of the Serbian State Security Service Franko Simatović “were charged with having directed, organised, equipped, trained, armed and financed units of the Serbian State Security Service which murdered, persecuted, deported and forcibly transferred non-Serb civilians from Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) and Croatia between 1991 and 1995.”54 In its ruling, the court found that Stanišić and Simatović could not be held criminally liable for crimes committed by the units that they had organized, led, and paid.55 Since this first ruling, however, the appeals chamber has ordered a retrial of the case, which has now been transferred to the MICT.56

In addition to these contentious rulings on command responsibility, the ICTY also made a divisive ruling this past March when it acquitted Serbian nationalist Vojislav Šešelj of crimes against humanity and war crimes.57 Šešelj “was accused of having directly committed, incited, aided and abetted” crimes committed by Serbian forces from August 1991 until September 1993.58 Additionally, he was accused of having taken part in a “joint criminal enterprise (JCE)” to create a “Greater Serbia.”59

During the war, as head of the Serbian Radical Party, Šešelj mobilized groups of volunteer fighters, known as Šešelj’s men, for whom he provided money and weapons.60 The tribunal “concluded that the objective of the creation of Greater Serbia was more of a political venture than a criminal project” and that the crimes committed in the process of achieving this objective could not be attributed to Šešelj, as they were carried out by fighters under the command of the military and police.61 Further, the tribunal found that while Šešelj had certainly made inflammatory speeches that incited hatred of the non-Serbian population, they “could not rule out the reasonable possibility” that the speeches “were meant to boost the morale of the troops of his camp.”62

Exacerbating the controversy surrounding the verdict was the fact that it took nearly 13 years from the time Šešelj surrendered to his acquittal earlier this year. Certainly, some of the blame for the lengthy proceedings can be laid at Šešelj’s own feet—he notoriously disrupted proceedings, went on a hunger strike, and was tried and convicted three separate times for contempt of court.63 However, this case laid bare the tribunal’s own sluggish pace, made particularly painful for many given the ultimate outcome.

The debate about some of these hot-button ICTY cases will continue. Did prosecutors make poor cases, or did judges allow commanders too much leeway for plausible deniability of forces acting under their orders? Certainly, the slow pace of the court, and the varying level of professionalism displayed by judges and prosecutors in its early years,64 reflected some very real growing pains. But at the same time, the Yugoslav tribunal clearly helped pave the way for the International Criminal Court, made groundbreaking strides forward in dealing with rape as a weapon of war, and sent a positive international signal that perpetrators of war crimes and crimes against humanity would be held accountable, even if it took time and expense to do so.

International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR)

On November 8, 1994, following Rwanda’s 100-day genocide in which some 800,000 people were killed, the U.N. Security Council adopted Resolution 955 establishing the ICTR.65 The tribunal was mandated to prosecute “persons responsible for genocide and other serious violations of international humanitarian law” committed in Rwanda and in neighboring states between January 1, 1994, and December 31, 1994.66

Although the Rwandan government requested the tribunal, it actually voted against Resolution 955—objecting to the temporal jurisdiction of the court, the fact that the tribunal would not employ the death penalty, the scope of the crimes to be tried by the court, and the location of the tribunal in Arusha, Tanzania, believing the trials should take place near where the crimes occurred.67 Despite these objections, the tribunal moved forward and opened in 1995 with its headquarters in Arusha and offices in the Rwandan capital of Kigali. The appeals chamber is located in The Hague, Netherlands.68

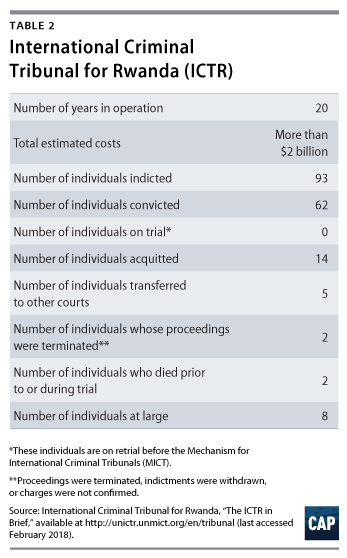

The ICTR was the first international tribunal to deliver verdicts against those responsible for genocide since the adoption of the 1948 Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide.69 It was also the first tribunal to define rape in international criminal law and to “recognise rape as a means of perpetrating genocide.”70 The ICTR delivered its final trial judgment on December 20, 2012, and formally closed on December 31, 2015.71 However, the tribunal’s outstanding work now rests in the Mechanism for International Criminal Tribunals.72 Of the eight remaining fugitives who have been indicted by the court, the MICT would try three if and when they are apprehended; the remaining five would be referred to Rwanda for trial.73 Total estimated costs of the tribunal were more than $2 billion.74

Starting with a numerical overview, during its 20 years of operation, the tribunal indicted 93 individuals, of whom:

- 62 were convicted.

- 14 were acquitted.

- 10 were referred to national jurisdictions for trial; 5 of these remain fugitives.

- 2 had their indictments withdrawn before trial.

- 2 died prior to or during trial.

- 3 other fugitives have also been referred to the MICT.75

It should be noted, though, that the tribunal did not prosecute any alleged crimes committed in 1994 by the predominantly Tutsi rebel group, the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), that came into power after the genocide. The RPF—a group that had been fighting to overthrow the Rwandan government prior to the genocide—effectively ended the genocide when it took military control of the country, and the extent of its reprisal killings of thousands of mostly Hutu civilians remains hotly debated.76 Current Rwandan President Paul Kagame formerly led the RPF.77

Similar to the ICTY, many of the ICTR’s major accomplishments arose from groundbreaking cases related to sexual and gender-based violence. In the Akayesu case, in which the head of the Taba commune, Jean-Paul Akayesu, was accused and convicted for his role in the violence and killings during the genocide, the tribunal defined the crime of rape for the first time in international criminal law while recognizing rape as an instrument of genocide and a crime against humanity.78 Additionally, with this case, the ICTR became the first international tribunal to enter a judgement for genocide, as well as the first to interpret the 1948 Geneva Conventions definition of genocide.79 In the Nyiramasuhuko et al. case, the tribunal found Pauline Nyiramasuhuko—who had been serving as a minister for family and women’s affairs—guilty of genocide and rape as a crime against humanity, the first time a woman has been convicted of such crimes.80

The tribunal also had other important milestones related to the expansion of genocide case law. In the Kambanda case, the tribunal became the first to convict a former head of state since the adoption of the Geneva Conventions in 1948.81 This case also marked the first time an accused pled guilty to genocide, conspiracy to commit genocide, and crimes against humanity.82 In another landmark case that came to be known as “the media case,” the tribunal found three members of the media—Jean-Bosco Barayagwiza, Ferdinand Nahimana, and Hassan Ngeze—responsible for broadcasts meant to incite the public to commit genocide.83 This verdict marked the first time an international tribunal held members of the media accountable for the crime of genocide. Additionally, the appeals chamber later confirmed in this case that superior responsibility also applied to civilians in leadership positions and not just to members of the military.84

Much of the controversy surrounding the ICTR has been tied to the tribunal’s relationship with the Rwandan government and the national courts. As mentioned previously, the Rwandan government voted against the Security Council resolution establishing the tribunal the government had initially requested.85 Rwandan officials wanted the court’s jurisdiction to cover crimes from 1990 to July 1994, instead of December 1994. Many believe this was because the new government did not want reprisals against Hutus explored.86 In this same vein, the Rwandan government also wanted to limit the scope of crimes investigated to genocide, again excluding crimes the RPF may have committed.87 And while the court was given jurisdiction over alleged crimes committed by the RPF, it ultimately did not bring forward any cases against RPF members. The tribunals’ reluctance to pursue justice for crimes committed by RPF members has led to some criticisms that the court “provided only victor’s justice.”88

Additionally, the government objected to the limitations on penalties for those convicted at the tribunal. At the time of the tribunal’s creation, Rwandan law permitted individuals to be given the death penalty, while the tribunal limited penalties to imprisonment. This created a situation whereby the most culpable leaders of the genocide could receive less severe punishments than those at a lower rank convicted of lesser crimes.89 This discrepancy in punishments between the tribunal and the national courts added to tensions between the two institutions and exacerbated feelings of many Rwandans that leaders of the genocide were receiving leniency. Further, the Rwandan government believed that having the court in Arusha, so far away from the scene of the crimes, undermined the deterrence effect of the trials.90

Despite these initial objections, the Rwandan government eventually pledged cooperation with the tribunal.91 However, this cooperation was put to the test several times, particularly as France, Rwanda, and other actors have continued to contest vehemently the parties responsible for the shooting down of former President Juvénal Habyarimana’s plane, the spark which marked the onset of the genocide.92 Tensions between the ICTR and the Rwandan government also came to a head when the appeals chamber acquitted and released Justin Mugenzi and Prosper Mugiraneza in 2013, both of whom had originally been convicted of conspiracy to commit genocide and for direct and public incitement to commit genocide.93 As a result of these acquittals, the Rwandan government threatened to dismiss ICTR monitors if the court “continue[d] to act with impunity,” and hundreds of genocide survivors protested outside the tribunal’s Kigali offices.94

In part because of the scope of the killings in Rwanda, a variety of mechanisms have been deployed on the justice front. More than 120,000 people were detained for their connections to the mass killings in Rwanda, and the ICTR obviously only dealt with a small fraction of those cases. Rwandan national courts addressed many of these cases, and because of the significant backlog in dealing with the large number of cases, Rwanda re-established a traditional justice mechanism, the “Gacaca court system,” where local-level elected judges would hear the cases of those involved in alleged killings.95 Some cases before the Gacaca led to rapid use of the death penalty. Yolande Bouka, a researcher with the Institute for Security Studies who is based in Nairobi, said, “some of the first individuals to be arrested, tried, and convicted of genocide [by the Gacaca] were executed without providing the world with much information about the intricacies of their role or what they knew about others involved in the genocide.”96 Many of these Gacaca cases, however, did not result in prison time but rather in community service or forgiveness for alleged perpetrators.97

The legacy of the ICTR is mixed. Some Rwandans criticized the international tribunal for its cost, lack of speed, and limited number of convictions—all concerns that have some merit.98 And the failure of the tribunal to investigate reprisal killings by Tutsis of Hutus—though not taking place on nearly the same scale of Hutu killings of Tutsis—was a major concern. Like the Yugoslav tribunal, the growing pains of the ICTR in even its most basic operation were evident in its early years, and the sheer scale of the genocide almost always ensured that full justice and accountability would be a daunting prospect. The push for international justice was also complicated by the role of international actors, particularly France, in its earlier support for the Hutu regime that conducted the genocide.99

Special Panels for Serious Crimes (SPSC) in East Timor

On June 6, 2000, the United Nations Transitional Administration in East Timor (UNTAET)—the interim civil administration and peacekeeping mission established by the United Nations in 1999 to oversee East Timor’s transition from an Indonesian territory—passed Regulation No. 2000/15 establishing the Special Panels for Serious Crimes (SPSC) in East Timor to examine crimes that had occurred as part of East Timor’s struggle for independence from Indonesia.100 Indonesia’s rule over East Timor was notoriously repressive—an estimated 200,000 East Timorese died as a result of human rights violations committed between April 1974 and October 1999.101 The panels had jurisdiction over the serious criminal offenses of genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity committed before October 25, 1999; the panels’ temporal jurisdiction over the serious crimes of murder, sexual offenses, and torture was limited to January 1 to October 25, 1999.102 The panels were housed in-country, and in May 2002, responsibility for the SPSC was transferred to the new East Timor government, after which time the United Nations continued to provide funding for investigations and trials.103

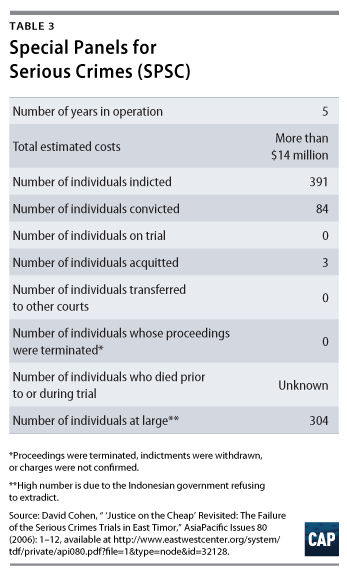

The establishment of the SPSC was a somewhat unique hybrid justice process in that it was established by a U.N. mission and represented an attempt to embed a U.N. tribunal within the newly created Timorese justice system.104 To this end, each court was composed of two international judges and one Timorese judge.105 In 2004, the U.N. Security Council decided to end the East Timor mission and stated that SPSC investigations should be completed and trials concluded no later than May 20, 2005, at which time the SPSC was effectively—and arguably prematurely—closed.106 The total operating cost of the SPSC and its investigating unit, the Serious Crimes Unit (SCU), was a little more than $14 million, a miniscule amount compared with the costs of either the Yugoslav or Rwanda tribunals.107

During its five years of operation, the SPSC indicted 391 individuals, of whom:

- 84 were convicted.

- 3 were acquitted.

- 304 remain at large.108

The main reason behind the high number of individuals indicted who remain at large is that the vast majority of them reside in Indonesia, which formerly ruled East Timor with a heavy hand, and the Indonesian government has refused to extradite them. As a result, most of those convicted were low-level perpetrators, with only a few relatively lower-ranking members of the Indonesian army in the mix.109 Additionally, due to its early closure, the court was unable to complete all the investigations and trials for those it indicted—not to mention the many other serious crimes that the court was unable to investigate. It should also be noted that the numbers above reflect the status of individuals at the time of the court’s closure in 2005.

The United Nations has maintained that the court was overall a success, often pointing to the high number of convictions and the completion of cases by the May 20, 2005, closure. Unfortunately, for a number of reasons, the SPSC has been heavily criticized as a flawed mechanism by outside experts. In one such critique, analyst David Cohen described the tribunal as “a virtual textbook case of how not to create, manage, and administer a ‘hybrid’ justice process.”110 Some of the main criticisms of the court include that it lacked adequate resources, staff, and management; it operated with no prosecutorial strategy for its first two years as a result of an unclear mandate; its jurisprudence and procedures were at times deeply flawed; and there was inadequate political will and support from the United Nations and international community for the court to perform all its functions effectively.111

More specifically, the United Nations never appointed someone to head the panels, and a permanent head for the SCU was only appointed in 2002.112 Without a powerful figure to advocate for them, the panels were not given the resources necessary to fulfill their duties comprehensively.113 And early on, the panels had a shortage of competent defense lawyers and almost no translation and transcription services.114 Further, the court never established a witness protection program. As Cohen notes in his critique, “witnesses and victims coming to Dili [the capital of East Timor] sometimes rode in the same minibus as the accused they were to testify against—including in sexual violence cases.”115

Deficiencies in defense counsel, translation and transcription services, and a complete absence of a witness protection program called into question the court’s procedures and subsequent judgements and delegitimized the court in the process. The court also issued some judgements that appeared significantly flawed, including in the case against Rusdin Maubere, an Indonesian soldier who was indicted for crimes against humanity for the use of enforced disappearances and torture.116 In the court’s judgement, Maubere was convicted of murder as a crime against humanity—a crime for which he had not been charged nor allowed to defend against and for which no new evidence was introduced.117 This judgement appeared to represent a violation of the accused’s right to a fair trial and due process.

Similarly, if not more, troubling, was the fact that the United Nations was aware of many of these deficiencies and did not try to ameliorate them until the panels were nearing their end.118 The United Nations also did not always provide the strong support the panels needed to obtain justice—namely, when indictments were issued for high-ranking officers. Further, the United Nations lacked the political will to keep the court running, instead opting to cease the court’s operations prematurely. As a result of this premature closure, some lawyers noted that there was added pressure to agree to plea bargains, some defenses were cut short, and no new trials could commence after mid-2004.119 This also meant that justice was not wholly served.

In January 2007, the United Nations tried to address these gaps in justice through the creation of the Serious Crimes Investigation Team (SCIT). Established as part of the United Nations Integrated Mission in Timor-Leste (UNMIT), SCIT’s primary purpose is to “resume the investigative functions of the former Serious Crimes Unit (SCU) and to address the outstanding cases of serious human rights violations committed in the country in 1999.”120 As SCIT did not have prosecutorial powers, it could only assist the Office of the Prosecutor General of Timor-Leste in bringing perpetrators to justice.121 Although it had some of its own issues,122 after the expiration of SCIT’s mandate in 2013 following the withdrawal of UNMIT in 2012, SCIT had completed more than 300 investigations, leaving roughly 60 investigations incomplete.123

In addition, an independent Commission for Reception, Truth, and Reconciliation was established in 2002 that held extensive national and local hearings, established a public archive of documentation, and offered restitution to victims.

While the Timor tribunal was not as high-profile as those in Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia, it does offer some important lessons. First and foremost, real accountability cannot be expected on the cheap and with a rapid timetable. Standing up credible judicial proceedings requires a real investment of resources, and investigations and hearings can often take years to come to fruition. Unfortunately, the Timor tribunal often looked like it was designed to demonstrate that the international community cared about accountability without actually taking the difficult steps needed to ensure that it was achieved.

Special Court for Sierra Leone (SCSL)

In 2000, the government of Sierra Leone requested that the United Nations establish a special court to address crimes committed against civilians and U.N. peacekeepers during the country’s 1991–2002 civil war, during which roughly 50,000 people are estimated to have been killed.124 Some of the tactics during the war were particularly brutal, including the widespread cutting off of noncombatants’ arms.

As a result, on January 16, 2002, the United Nations and the Sierra Leone government signed an agreement to establish a Special Court for Sierra Leone (SCSL).125 The agreement stipulated that the SCSL try those “who bear the greatest responsibility for the commission of serious violations of international humanitarian law and crimes committed under Sierra Leonean law” committed in Sierra Leone after November 30, 1996.126 Unlike its Yugoslav and Rwandan predecessors, the SCSL was the first modern tribunal to be situated in the country in which the crimes took place.127

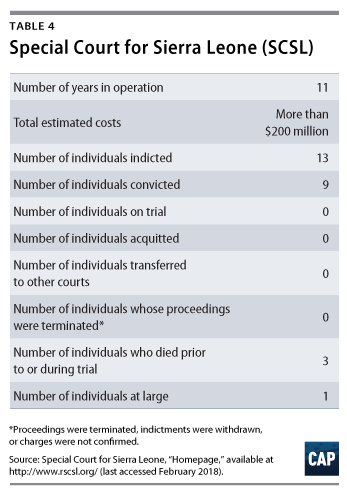

The SCSL was the first ad hoc hybrid international criminal tribunal—a judicial body that mixed both national and international law and employed both national and international staff. Also, with the case against Charles Taylor, the former president of Liberia and brutal warlord who supported the Sierra Leone rebels behind some of the worst mass atrocities, the court became the first tribunal since Nuremberg to indict, try, and convict a sitting head of state.128 Further, it was the first international tribunal to be funded by voluntary contributions and the first to complete its mandate and transition to a residual mechanism, which it did in 2013.129 The Residual Special Court for Sierra Leone (RSCSL), was established following the SCSL’s formal closure in 2013 to handle any continuing legal obligations, such as “witness protection, supervision of prison sentences, and management of the SCSL archives.”130 Total estimated costs of the court were more than $200 million.131

Turning to numbers, during its 11 years of operation, the SCSL indicted 13 individuals, of whom:

- 9 were convicted.

- 3 died—1 before proceedings, 1 outside the court’s jurisdiction, and 1 during the course of his trial.

- 1 remains at large—the chairman of the Armed Forces Revolutionary Council (AFRC), Johnny Paul Koroma, fled the country before his indictment and is widely rumored to be dead, though this has not been confirmed.132

The court also conducted trials relating to threats against a protected witness in 2005 and three trials in from 2011 to 2013 related to witness tampering.133

Despite its relatively small caseload compared with those of its predecessors in Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia, several notable legal precedents came out of the special court that have added greatly to international jurisprudence. In a joint trial against the leaders of the Armed Forces Revolutionary Council, known as the AFRC case, the court became the first to try and convict individuals for the use of child soldiers.134 In the judgement of a separate joint trial against leaders of the Revolutionary United Front, known as the RUF case, the court ruled for the first time that forced marriage was a crime against humanity.135 Additionally, with this case, the court became the first to try and convict individuals for attacks directed against U.N. peacekeepers.136

There have been critiques of the court related to controversial appointments of internationals to high-level positions by the Sierra Leone government. The most controversial of these was the appointment of Desmond Lorenz de Silva—a U.K. lawyer originally from Sri Lanka—as the deputy prosecutor.137 The agreement establishing the court stipulated that the government appoint a Sierra Leonean deputy prosecutor, but the government quietly amended the agreement to allow de Silva’s appointment.138 Additionally, the government chose to nominate only two Sierra Leoneans as judges out of its four available nominations.139 These decisions caused consternation among Sierra Leonean lawyers and added to the perception that the court was an international one rather than being a true hybrid.

Other issues surrounded the court’s narrow interpretation of the legal construct—“those bearing the greatest responsibility”—which ultimately led to a small number of indictments.140 By prosecuting such a limited number of perpetrators, there was a widespread perception in Sierra Leone that many individuals were not held accountable for their actions.141 However, others welcomed the court’s narrow focus, an approach that the ICC later adopted to be more efficient.142

As with a number of countries cited in this report, Sierra Leone also established a Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which operated from 2002 to 2004.143

The International Center for Transitional Justice argues that the legacy of the Sierra Leone tribunal is mixed. On the positive side, the hybrid nature of the court helped build the capacity and experience base of jurists from Sierra Leone and encouraged some measure of judicial reform.144 On the less positive side, there was never full clarity with the public on the role of the tribunal versus that of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. As the International Center for Transitional Justice commented, “Questions will linger about whether limiting the number of accused renders justice that is pragmatic and satisfactory, or whether it is ultimately incomplete.”

In terms of significance, the successful 2012 prosecution of Liberian President Taylor on 11 counts of aiding and abetting crimes against humanity and war crimes in neighboring Sierra Leone sent a powerful message that even heads of state could not act with impunity. Taylor is now serving a 50-year jail sentence in the United Kingdom.145 The Sierra Leone tribunal also represented an important effort to blend international justice with an effort to build up local capacity and mechanisms for accountability as a country tries to emerge from conflict.

Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC)

In 1997, the Cambodian government requested assistance from the United Nations to organize a process for holding trials related to crimes committed by the Khmer Rouge regime. The rule of the Khmer Rouge, which lasted from April 17, 1975, to January 6, 1979, was one of the most brutal of the 20th century.146 It is estimated that 1.7 million people were killed by the Khmer Rouge, more than one-fifth of the Cambodian population at the time.147

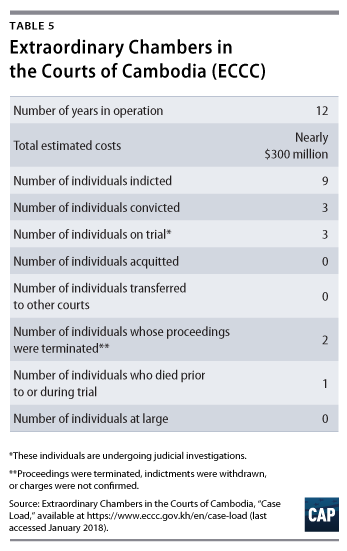

However, it was not until years later and after extensive negotiations that this justice mechanism was established, complicating an already difficult search for justice. After the passage of domestic legislation following an agreement between the Cambodian government and the United Nations in 2003, the ECCC was set up in 2006 as an “ad hoc Cambodian court with international participation.”148 According to the legislation, the court is mandated to “bring to trial senior leaders and those most responsible for crimes committed during the time of Democratic Kampuchea, also known as the Khmer Rouge regime.”

The ECCC is located in Cambodia and is a hybrid tribunal, employing both national and international staff and able to apply both national and international law.149 Officially set up 27 years after the fall of the Khmer Rouge regime, the ECCC is one of the most temporally distant tribunals ever established—more than 65 percent of Cambodians today were born after the fall of the regime.150 As of March 2017, the court had spent a total of just more than $290 million.151

In its 12 years of operation, the Extraordinary Chambers has indicted nine individuals, of whom:

- 3 have been convicted.

- 3 are undergoing judicial investigations.

- 1 was found unfit to stand trial.

- 1 had their case dismissed.

- 1 died prior to trial.152

Due to the fact that the court was established long after the events it was mandated to investigate, a number of the senior Khmer Rouge leaders have died, which partially explains the small number of indictments. The co-prosecutors at the court have publicly stated that there will be no additional cases.153

One very positive and unique aspect of the chambers has been the vast participation by the Cambodian people in witnessing the trials. Since the start of the first trial in 2009 through February 2015, 165,407 people have witnessed the trials in person—more than the total number of spectators for the Nuremberg and Tokyo tribunals, the ICTR, the ICTY, the SCSL, the Special Tribunal for Lebanon, and the ICC combined.154 Still more Cambodians have watched the trials on television over the years as well. Additionally, the court has undertaken efforts to conduct outreach to the public to inform them about the court, which includes a weekly radio program. According to the most recent statistics put out by the court in September 2017, the court’s various outreach activities have reached almost 560,000 people.155 All of this speaks to the enormous pent-up demand in Cambodia for accountability and justice.

On balance, however, the tribunal has been quite disappointing, and a number of steps have called the court’s legitimacy into question. Perhaps foremost of these has been the issue of political interference in the tribunal from the Cambodian government, which can be traced back to the court’s formation. Hun Sen, Cambodia’s prime minister, who was been in power since 1985, initially rose to power as a battalion commander with the Khmer Rouge, before defecting amid violent purges and helping lead a Vietnamese-backed rebel army that eventually overthrew the Khmer.156 Hun Sen has frequently been accused of both political violence and corruption, and it is unsurprising that he would want to carefully circumscribe the search for justice in Cambodia.

In 1997, after the Cambodian government officially requested assistance from the United Nations in establishing a tribunal to prosecute former Khmer Rouge leaders, U.N. Secretary-General Kofi Annan commissioned a Group of Experts to assess the country’s judiciary in order to ascertain whether it could legitimately contribute to such a court.157 In their assessment report, the experts found serious deficiencies in the judicial system, including close alliances between judges and the leading political party and a high level of corruption.158 As a result, the experts could not recommend that a hybrid court be established, as “such a process would be subject to manipulation by political forces in Cambodia.”159

Despite these concerns and following the Cambodian government’s rejection of the experts’ findings, the United Nations began to pursue negotiations with the Cambodian government to create just such a hybrid tribunal.160 In the eventual agreement between the United Nations and the Cambodian government, the ECCC was designed as a domestic court with international participation. And while the agreement stipulated that the court must act in accordance with international standards and maintain its independence and impartiality, appropriate safeguards were not put in place for the selection of local judges, which allowed for considerable political interference from the Cambodian government.161

One example of this interference came to the fore with investigations against Khieu Samphan, former head of state; Nuon Chea, former deputy secretary of the Communist Party of Kampuchea and former Prime Minister Pol Pot’s second in command; Ieng Sary, former foreign affairs minister; and Ieng Thirith, former social affairs minister.162 During the investigations, the government had publicly expressed opposition to the hearing of six high-level witnesses close to the government, declaring that they should not testify.163 As a result, these witnesses did not provide testimony in the investigations, and the investigating judges did not undertake additional measures to pursue the matter. In 2009, in response, the defense attorneys requested that the court investigate the potential government intimidation of the witnesses, to which the Cambodian judges responded by stating that such an investigation was not warranted, while the internationally appointed judges issued strongly dissenting opinions.164

In 2010, the Cambodian government also made attempts to stop additional prosecutions beyond those in Case 002 against Khieu Samphan and Nuon Chea, with Prime Minister Hun Sen even going so far as to tell U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon that no more prosecutions beyond these would be allowed for the sake of the country’s peace and stability.165 However, the government is not permitted to make decisions about future cases—the court alone has the responsibility for deciding whether additional cases proceed.

Then, in 2011, the defense counsel submitted a criminal complaint claiming that Hun Sen and other senior government officials had interfered with justice and the defendants’ right to a fair trial. The complaint claimed that government officials indicated that certain witnesses not testify; opposed further investigations and proceedings; breached court summonses to appear for testimony without valid reasons; and prevented court letters inviting a witness to testify from reaching him.166 In response to the defense counsel’s request that the Office of the Royal Prosecutor (ORP) initiate criminal proceedings in regard to this filing, the ORP decided to file the complaint but failed to conduct an independent investigation and did not process it, citing a lack of evidence.167 Such political interference on the part of the Cambodian government has cast serious doubts on the court’s legitimacy and has even led several international judges to resign.168 While additional cases have proceeded despite government interference, trust in the court’s ability to achieve justice for crimes committed under the Khmer Rouge has unfortunately eroded.

In many ways, the Cambodia tribunal appears to be a textbook model of how not to pursue international justice. The U.N. Group of Experts clearly recognized that the Cambodian government was not positioned to give a fair hearing to the grave crimes committed, yet a tribunal was established that effectively gave Hun Sen’s government veto power over the court at key junctures. What played out in Cambodia clearly highlights the need for international justice when national governments lack the will or ability to pursue such cases fairly.

Special Tribunal for Lebanon (STL)

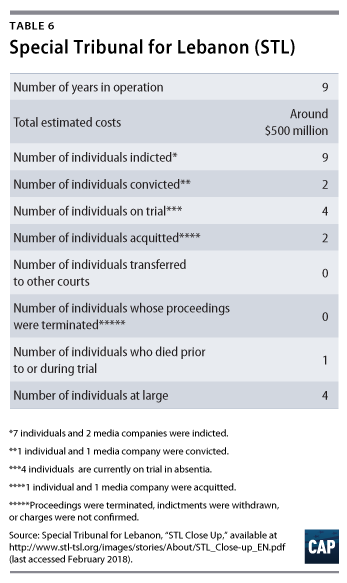

In December 2005, the government of Lebanon requested that the United Nations create a tribunal of “international character” to help investigate terrorist bombings that had occurred earlier in the year. Those bombings killed former Lebanese Prime Minister Rafik Hariri and 21 others.169 On January 23, 2007, the United Nations and the Lebanese government signed an agreement to establish the Special Tribunal for Lebanon (STL).170 On May 30, 2007, the STL was formally established by the U.N. Security Council with the adoption of Resolution 1757.171 This resolution gave the Lebanese Parliament until June 10, 2007, to ratify the agreement establishing the tribunal, after which time the tribunal would enter into force.172 When the Lebanese Parliament did not ratify the agreement, the STL became the first treaty-based tribunal in the history of the United Nations to be enforced by a resolution under Chapter VII of the U.N. Charter,173 which allows the Security Council to determine “the existence of any threat to the peace, breach of the peace, or act of aggression.”174

The STL is mandated to prosecute those responsible for the February 14, 2005, attack in Beirut that killed 22 people. With the consent of the Security Council, the tribunal is also permitted to exercise jurisdiction over other attacks in Lebanon between October 1, 2004, and December 12, 2005, if these attacks “are connected in accordance with the principles of criminal justice and are of a nature and gravity similar” to the February 14, 2005, attack.175 Headquartered near The Hague, the STL is composed of both international and national staff, but unlike other hybrid mechanisms discussed, the STL’s jurisdiction is limited to crimes under domestic Lebanese law.176 As the tribunal operates in accordance with Lebanese law, it is permitted to hold trials in absentia, whereby it is not necessary for the accused to participate in or be present for proceedings.177 Estimated costs of the tribunal are around $500 million,178 49 percent of the cost funded by the Lebanese government, according to the tribunal.179

In its nine years of operation, it has indicted seven individuals and two media companies, of whom:

- 2 were convicted and fined—1 individual and 1 media company.180

- 4 are currently on trial in absentia.

- 2 were acquitted—1 individual and 1 media company.

- 1 died during his trial in absentia.181

The two convictions and acquittals were for cases involving contempt and obstruction of justice charges related to the alleged broadcasting of information about confidential witnesses.182 The tribunal has also established jurisdiction over three other attacks connected to the main Ayyash et al. case concerning the February 11 attack in which four individuals—Salim Jamil Ayyash, Hassan Habib Merhi, Hussein Hassan Oneissi, and Assad Hassan Sabra—are being tried in absentia. The pretrial judge has ordered Lebanese authorities to provide relevant files to the court’s prosecutors.183

The STL is the first tribunal to define terrorism as an international crime and to deal with terrorism as a distinct crime.184 This is due largely to the fact that the tribunal’s narrow mandate does not allow for the prosecution of international crimes, such as crimes against humanity. Instead, the mandate refers to terrorism crimes as defined under Lebanese law. Despite this original definitional limitation, the appeals chamber made a ruling in 2011 that allowed the tribunal to define terrorism using both Lebanese and international law.185

The STL is obviously quite different than the other tribunals discussed, in that it is motivated by a desire to bring accountability for a single terrorist attack rather than the widespread war crimes and crimes against humanity cited in the preceding examples. Further complicating the tribunal’s legacy has been the effort to try the primary alleged perpetrators in absentia. The Yugoslav, Cambodia, and Rwanda tribunals, as well as the ICC, have all placed a very high bar on the use of trials in absentia, viewing them as a last resort.186

The experience to date suggests that using an international tribunal to hold terrorism suspects to account has some very clear limits. The forensic and investigative work that led to the charges against Hezbollah operatives in the assassination has been impressive, made possible by the enormous resources the international community has put into the STL. That said, the Lebanese government has been unwilling to attempt to capture the Hezbollah suspects linked to the crime, and Hezbollah itself has declared that such a move could potentially trigger renewed civil war in Lebanon.187

Other justice mechanisms

Before turning to the role of the International Criminal Court, there are two other international tribunals of note that have developed during the past 25 years. The Extraordinary African Chambers was a tribunal created in 2013 by the African Union for the purpose of prosecuting “international crimes committed in Chad between 7 June 1982 and 1 December 1990.”188 The activities of the chamber are carried out in Senegal with the cooperation of the Senegalese government. This tribunal was created after extensive and somewhat contentious disputes about who had the right to prosecute Hissène Habré—the president of Chad from 1982 to 1990.

As the International Justice Resource Center notes, the Extraordinary African Chambers represents the first “body to be established within one State’s judiciary for the purpose of prosecuting another country’s former head of state, in exercise of its obligation to extradite or prosecute.”189 The tribunal differs from other previously established international and hybrid courts in that “it is possible that [it] may only prosecute a single individual: Hissène Habré.”190 In May 2016, Habré was found guilty of a variety of charges, including ordering the deaths of 40,000 people, rape, and sexual slavery. He was sentenced to life in prison.191

Following amendments to a 1973 statute, in 2010, Bangladesh set up a domestic International Crimes Tribunal to investigate and prosecute those responsible for mass deaths, systematic rape, and other profound abuses surrounding the split between West and East Pakistan in 1971, which is widely labeled as a genocide perpetrated by the Pakistani military and militias working in concert with it. (East Pakistan became Bangladesh after this split.) The name of the tribunal is somewhat misleading in that it functions entirely as a domestic Bangladeshi court. The tribunal has indicted a number of suspects, largely coming from the Jamaat-e-Islami, a large Bangladeshi political party that opposed the split with West Pakistan. Pakistani military officials implicated in the genocide have been beyond the reach of the tribunal.192

Nonetheless, the tribunal has secured a number of convictions, and penalties have included life imprisonment and death by hanging. The tribunal has also faced criticisms, with Brad Adams of Human Rights Watch stating in 2013, “The trials against the alleged mutineers and the alleged war criminals are deeply problematic, riddled with questions about the independence and impartiality of the judges and fairness of the process.”193

International Criminal Court

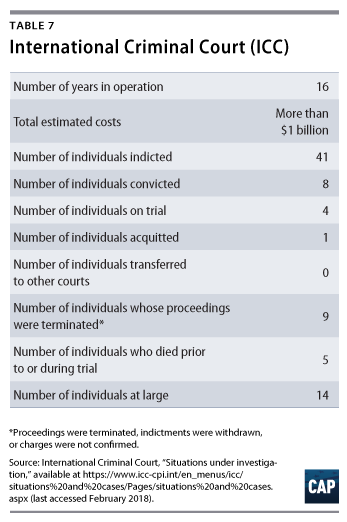

The International Criminal Court was established 20 years ago, on July 17, 1998, with the adoption of the Rome Statute by 120 states, which provided the legal basis for the court.194 The Rome Statute entered into force on July 1, 2002, after it was ratified by 60 countries, and it can only exercise temporal jurisdiction from that time onward. The ICC represents the first permanent international criminal court, and as laid out in the Rome Statute, it is a court of last resort and is meant only to try those accused of “the most serious crimes of concern to the international community”—namely, genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes.195 However, the statute also includes provisions for the court to exercise jurisdiction in the future over the crime of aggression.

The court can exercise its jurisdiction over states that have become parties to the Rome Statute by signing and ratifying the treaty, or states that have accepted the court’s jurisdiction through other means. The court may also exercise jurisdiction over a state if crimes are referred to it by the U.N. Security Council. Additionally, the court can exercise jurisdiction over individuals who are nationals of a state party to the Rome Statute, even if their alleged crimes took place in a state that is not a party to the Rome Statute.196 Some 139 countries have signed the Rome Statute, and 123 countries are currently states parties to the Rome Statute. They include 33 African states; 19 Asia-Pacific states; 18 Eastern European states; 28 Latin American and Caribbean states; and 25 Western European and other states.197

In the ICC’s 16 years of operation, there have been 24 of what the ICC calls country “situations,” which are essentially incidents being examined by the court. The court will first open a preliminary examination into a situation to determine whether it meets the legal criteria of the Rome Statute to then be investigated by the Office of the Prosecutor, at which point, depending on what the investigation yields, the ICC prosecutor can bring forth charges related to specific situations.198 From the 24 situations that have been examined by the court, it has moved forward with 25 cases (two of which involved offenses against the administration of justice) and 41 individuals (seven of whom were charged with offenses against the administration of justice) brought before the court. As a result:

- 8 individuals have been convicted, 4 of whom were convicted of major crimes (genocide, war crimes, and/or crimes against humanity).

- 4 individuals are on trial.

- 1 individual has been acquitted.

- 9 individuals have had their cases closed/been released/had charges unconfirmed.

- 5 individuals are deceased.

- 14 individuals are at large or not in ICC custody.

These cases have come to the ICC via a number of different streams. Of the 24 situations the court has examined, investigated, and/or is currently investigating, 13 (54 percent) were initiated by the ICC’s Office of the Prosecutor; 8 (33 percent) were referred by governments desiring an ICC investigation of events that took place on their own soil; 2 (8 percent) were referred by the U.N. Security Council; and 1 (4 percent) was referred by a law firm acting on behalf of a government.199

What follows is a quick overview of each of the situations examined at the ICC since it entered into force in 2002.

Situations and cases

Uganda

In January 2004, the government of Uganda referred atrocities committed by the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), a rebel group notorious for using child soldiers, to the ICC. The focus is on “alleged war crimes and crimes against humanity committed in the context of a conflict between the LRA and the national authorities in Uganda since 1 July 2002”—the date at which the Rome Statute entered into force.200

- Status: Situation under investigation

- Legal proceedings:

- Dominic Ongwen, former brigade commander in the LRA: on trial for alleged crimes committed in 2004 at the Lukodi IDP camp201

- Joseph Kony, leader of the LRA: at large202

- Vincent Otti, former vice chairman of the LRA: dead203

- Okot Odhiambo, former deputy army commander of the LRA: dead204

- Raska Lukwiya, former deputy army commander of the LRA: dead205

Although the number of cases with regard to the LRA are small, all individuals appear to have played very senior command roles with the guerilla group. Ongwen, who is currently on trial, is charged with more than 70 counts of crimes against humanity and war crimes.206 LRA commander Joseph Kony remains at large despite an intensive international manhunt, including with the use, until recently, of U.S. special forces.207 Those suspects who have died since legal proceedings were initiated all did so violently, either in clashes with Ugandan government forces or due to internal power struggles within the LRA. The ICC mandate with regard to the LRA does not include alleged atrocities perpetrated by the LRA outside Uganda, which have been considerable, and the rebel group has largely operated in the Central African Republic and Eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo since being driven from Uganda.208 Some effort has been made by the ICC to broadcast Ongwen’s proceedings to populations that were affected by the LRA.209

Democratic Republic of the Congo

In April 2004, the government of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) referred the situation to the ICC, whose focus is on “alleged war crimes and crimes against humanity committed in the context of armed conflict in the DRC since 1 July 2002”—at which time the Rome Statute entered into force.210

- Status: Situation under investigation

- Legal proceedings:

- Bosco Ntaganda, former deputy chief of staff of the political group the Union des Patriotes Congolais (UPC) and commander of operations of its military arm, the Forces Patriotiques pour la Libération du Congo (FPLC): on trial211

- Thomas Lubanga Dyilo, founding member and former president of the UPC/FPLC: convicted for war crimes212

- Germain Katanga, former commander of the armed opposition group, the Force de Résistance Patriotique en I’Ituri (FPRI): convicted for war crimes and crimes against humanity213

- Mathieu Ngudjolo Chui, former leader of militia group the Front des Nationalistes et Intégrationnistes (FNI): acquitted214

- Callixte Mbarushimana, former executive secretary of armed rebel group the Forces Démocratiques pour la Libération du Rwanda – Forces Combattantes Abacunguzi (FDLR-FCA): charges not confirmed215

- Sylvestre Mudacumura, military commander of the FDLR-FCA: at large216

The 2012 verdict in the Lubanga case marked the ICC’s first and was a watershed moment for recognizing the plight of child soldiers in the DRC and achieving some justice for them. However, the case also demonstrated some serious issues at the court—the judgement against Lubanga even included criticisms of the Office of the Prosecutor for its conduct in this case, particularly with regard to verifying witness testimony.217 All the cases in the DRC involve senior leaders of militia or rebel groups engaged in the protracted civil war in the eastern part of the country. Given the situation in eastern DRC, it is important that a number of these senior leaders have been apprehended and are facing justice. And while the government has largely been supportive of the ICC’s work, it is also of note that no charges of abuse have been brought against the DRC military or government officials, leading to questions about the impartiality of the court.

In January 2016, the DRC amended its military and criminal codes to essentially incorporate the standards of the Rome Statute as general principles of law and to give civilian criminal courts responsibility for cases of crimes against humanity and genocide.218

Colombia

In June 2004, the Office of the Prosecutor started its preliminary examination after having “received numerous communications … in relation to the situation in Colombia.” According to the ICC, the examination has focused on “alleged crimes against humanity and war crimes committed in the context of the armed conflict between and among government forces, paramilitary armed groups and rebel armed groups,” as well as “on the existence and genuineness of national proceedings in relation to these crimes.”219 This examination is ongoing, and no formal charges have been brought. It also marks the first examination of incidents in the Americas.

- Status: Ongoing preliminary examination

Central African Republic

In December 2004, the government of the Central African Republic (CAR) referred the situation to the ICC, whose focus has been on “alleged war crimes and crimes against humanity committed in the context of a conflict in CAR since 1 July 2002, with the peak of violence in 2002 and 2003.”220

- Status: Situation under investigation

- Legal proceedings:

- Jean-Pierre Bemba Gombo, former leader of militia group the Mouvement de Libération du Congo (MLC): convicted for war crimes and crimes against humanity in one case,221 and for offenses against the administration of justice in another case222

- Aimé Kilolo Musamba, former defense counsel for Jean-Pierre Bemba Gombo: convicted for offenses against the administration of justice related to witness tampering223

- Jean-Jacques Mangenda Kabongo, former defense team member for Jean-Pierre Bemba Gombo: convicted for offenses against the administration of justice related to witness tampering224

- Fidèle Babala Wandu, member of Parliament in the DRC and deputy secretary general of the MLC: convicted for offenses against the administration of justice related to witness tampering225

- Narcisse Arido, defense witness for Jean-Pierre Bemba Gombo: convicted for offenses against the administration of justice related to witness tampering226

The conviction of Jean-Pierre Bemba for war crimes and crimes against humanity marked the first time the ICC issued a conviction for rape as a war crime and crime against humanity, as well as the first time the ICC “applied the principle of command or superior responsibility.”227 As the head of Human Rights Watch’s International Justice Program, Richard Dicker notes that in the Bemba case, the court’s interpretation of consent in the crime of rape was very important for the development of jurisprudence of this crime. Essentially, the prosecutors in the case were not required “to prove that the victim did not consent to the acts.” Instead, “lack of consent [was] inferred from coercive circumstances.”228 Bemba’s conviction was also significant in that he was a former vice president of the DRC and militia leader, and he was the only person arrested for war crimes in CAR during this period. The other convictions in this situation all relate to “offenses against the administration of justice,” similar to an obstruction of justice charge.229 Bemba’s forces had been deployed to CAR as part of an effort to put down a coup attempt against then-CAR President Ange-Félix Patassé.

Darfur, Sudan

In March 2005, the U.N. Security Council referred the situation in Darfur to the ICC, which opened an investigation in June of that year focusing on “alleged genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity committed in Darfur, Sudan, since 1 July 2002,” at which time the Rome Statute entered into force.230

- Status: Situation under investigation

- Legal proceedings:

- Bahar Idriss Abu Garda, former head of the United Resistance Front, a splinter of the rebel group Justice and Equality Movement (JEM): charges not confirmed231

- Abdallah Banda, head of the Justice and Equality Movement Collective-Leadership (JEM-CL): at large232

- Omar Al Bashir, president of the Republic of Sudan: at large233

- Ahmad Harun, formerly minister of the interior in Sudan, currently serving as governor of North Kordofan: at large234

- Ali Kushayb, leader of the militia group known as the Janjaweed: at large235

- Abdel Raheem Muhammad Hussein, minister of defense in Sudan, formerly Bashir’s special representative in Darfur: at large236

- Saleh Mohammed Jerbo Jamus, former chief of staff of the rebel group the Sudanese Liberation Army-Unity, which later merged with JEM: dead237

The Darfur investigation is most notable for bringing charges of genocide and crimes against humanity against Sudanese President Omar Hassan Al Bashir. (Sudan is not party to the Rome Statute, but the situation was referred to the ICC by the U.N. Security Council.) Bashir remains the only current head of state facing genocide charges. The decision to issue a warrant for Bashir was a deeply controversial one, with some arguing that it was clear overreach by the court and that the case for genocide was not entirely compelling. In addition, there have been numerous instances where Bashir has traveled outside Sudan, and countries that are signatories to the Rome Statute, such as South Africa, have been unwilling to turn him over to the ICC, as is their responsibility.238 No trials have taken place as a result of the Darfur investigation to date.

Iraq/United Kingdom

While it is unclear when the preliminary examination into the situation in Iraq/United Kingdom commenced, the Office of the Prosecutor initially terminated the examination on February 9, 2006. The examination was later reopened on May 13, 2014, after additional information was received by investigators. The examination is focused on “alleged crimes committed by United Kingdom nationals in the context of the Iraq conflict and occupation from 2003 to 2008, specifically concerning detainee abuse.”239

- Status: Ongoing preliminary examination

Venezuela