Introduction and summary

Advancing U.S. national interests requires getting migration policy right.

This is particularly true as large-scale dislocations of people in Central America and Venezuela reshape realities across the Western Hemisphere. The scale and character of these dislocations require a new approach to managing the movement of people in the Americas. This approach must disavow cruel and counterproductive efforts at deterrence, emphasize cooperation between neighbors, and recognize the fundamental humanity of those seeking a better life for themselves and their loved ones.

Any effective approach, in addition to domestic reforms,1 requires understanding what is fueling these mass dislocations. It also requires being clear on what is not happening; despite the toxic, nativist rhetoric and policy President Donald Trump regularly peddles, the United States is neither being invaded, nor does it face an unmanageable migration crisis.

This does not mean, however, that the United States can afford to ignore current migration dynamics in the Western Hemisphere. Fear and desperation have led millions of people to uproot themselves and seek safety and security far from home. This situation requires a serious and well-resourced response from Washington and its regional partners, who must boldly reimagine both U.S. and regional responses in the short, medium, and long term. Anything less will aggravate an already serious humanitarian crisis and contribute to political and economic instability in the Americas.

The United States is neither being invaded, nor does it face an unmanageable migration crisis.

As outlined in this report, to accomplish these goals the United States must look and work well beyond its borders to:

- Understand the underlying drivers of migration, including profound governance failures in the Northern Triangle of Central America; system failure in Venezuela; and the negative effects of climate change throughout the region

- Invest, at scale, in peace and democracy in the Americas in ways designed to address key migration drivers in both the immediate and longer term that are cheaper and more effective than the president’s doomed border wall and wildly misguided punitive tariffs

- Commit to a whole-of-society approach that ensures that responsibility for managing migration is shared by local, national, and regional civic, private, and government sector actors

- Adopt a humane and effective approach to immigration and border management that allows the United States to exercise arguably indispensable hemispheric leadership on migration and restore respect for the rule of law in its system

Properly understood and managed, migration represents not simply a challenge for the United States, but an opportunity. Advancing U.S. national interests requires a fundamental reassessment of current and recent approaches in the Americas, beginning with abandoning the policies of the current U.S. administration that are impeding effective national and regional responses to migration.

Migration in the Americas

During the past five years, dramatic shifts in the scale and character of migration in the Americas have unsettled regional politics and tested the capacity and political will of governments and international agencies to address and avert humanitarian crises. Violence, poverty, political dysfunction, and environmental degradation across the Western Hemisphere have led to an increase in refugees, asylum-seekers, and other vulnerable and displaced populations on a scale not seen in decades. The effects of these migrations on the economies and societies of the Americas have been profound and are likely to intensify in the months and years to come.

In the United States, much of the discussion surrounding migration has centered on the sharp increase in Central American asylum-seekers along the U.S. southern border since 2014. This development is a genuine challenge that has been aggravated by the cruel rhetoric and policies of the current administration toward migrants of all kinds. Inhumane and punitive practices such as child separation, detention in dangerous conditions, and myriad efforts to severely restrict the availability of protections for people requesting asylum have rightly drawn outrage, litigation, and renewed calls for an overhaul of U.S. immigration policy. In response to this outcry, President Trump has doubled down on irresponsible and inflammatory approaches by:

- Deploying the U.S. military to the southern border on an arguably unlawful mission2 to defend against a fictitious invasion of asylum-seekers from El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala

- Unilaterally and illegally diverting billions of dollars appropriated for military preparedness and construction to seize privately owned land and build a largely symbolic wall along portions of the southern border

- Threatening billions in tariffs to be paid by U.S. consumers if Mexico does not eliminate migration to the United States3

The Trump administration’s treatment of migrants is horrifying on its own terms, but it also represents a wrongheaded and myopic approach to addressing mass displacement of peoples in the Western Hemisphere. The Central American refugee crisis is not an isolated phenomenon. Rather, it is one aspect of a set of regional challenges that will not be solved at the border or through polices aimed at deterring specific populations from migrating. The drivers of mass migrations are complex and interrelated, and a crisis in one country can cause or aggravate migration pressures in others.

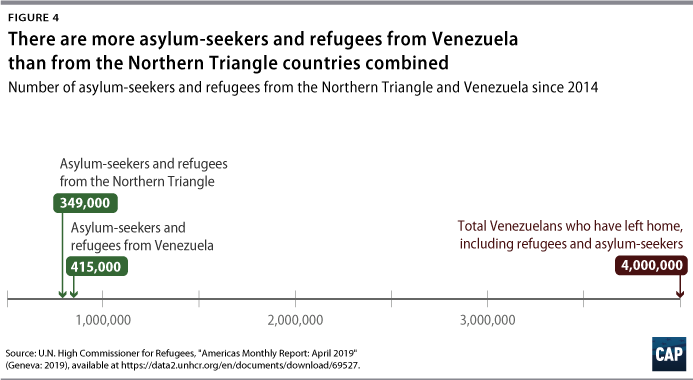

Many Americans may be surprised to learn that the movement of displaced persons within South America vastly exceeds northbound migration from Mexico and Central America toward the United States. By June 2019, there were more than 1.3 million Venezuelans living in Colombia, alongside 768,000 in Peru, and 130,000 in Argentina.4 A total of approximately 4 million Venezuelans have fled their homeland in recent years.5

Potential flashpoints for deepened humanitarian and geopolitical crises abound; a worsening of the political situation in Venezuela, a renewal of civil strife in the Caribbean, or a major climate catastrophe in Central America could significantly exacerbate migration dynamics in the Americas. Responding effectively to this challenge will require coordinated regional efforts that address the underlying drivers of mass migration and develop shared frameworks for processing vulnerable populations.

The United States can play a pivotal and arguably indispensable role in managing and reducing migration pressures in the Americas. It can and should provide the leadership and resources to drive collective responses from regional stakeholders and set a positive example in its own treatment of migrant populations.

Changing migratory flows

Taken at face value, President Trump’s demands for a wall along the U.S. southern border and his spurious claims of an “invasion” of migrants suggest that migration from Latin America to the United States is at unprecedented levels.6 The truth is far different.

Until recently, Mexican nationals represented the largest population of migrants seeking entry to the United States.7 Over the past decade, however, out-migration from Mexico has decreased dramatically, and apprehensions of Mexicans along the U.S. border are at near 40-year lows.8 The reasons for these changes in migration flows are complex, but the most important factors have been a reduction in employment opportunities in the United States following the 2008 recession and economic and demographic changes in Mexico that have reduced incentives to seek work abroad.9

As of late 2018, both Guatemalans and Hondurans were estimated to be crossing the U.S. border in greater numbers than Mexicans, an unprecedented development.10 Yet even this figure needs to be put in context: The number of Central Americans migrating to the United States has increased only slightly since 2013—although recent reporting on U.S. Border Patrol apprehensions suggests a notable increase in the past six months.11 Migration from South America has also decreased, with the notable exception of Venezuelans.12

These trends, however, do not tell the full story of migration in the Americas. While overall migration from Latin America to the United States has largely plateaued, the percentage of those migrants who are refugees and asylum-seekers has increased sharply, as discussed below. In addition, the Venezuelan political crisis and associated economic collapse that has sent millions of Venezuelan nationals fleeing to neighboring states have created ripple effects throughout the hemisphere. These developments mean that migrant populations in the Western Hemisphere are more diverse in terms of age and gender and are also more likely to be fleeing violence, persecution, and hardship.13

U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) definitions and meanings14

Any discussion of migration requires an understanding of the formal legal categories to which different migrant populations belong—and, by extension, the treatment to which they are entitled—under international and domestic laws. In most migration scenarios, the most important distinction is between individuals who claim to have left their home country because of fear of persecution—refugees and asylum-seekers—and those migrating for other reasons, such as to pursue better economic opportunities or to join family members who are already abroad. The following are some key concepts and terms pertaining to U.S. and international classification of migrants drawn from UNHCR materials.

1951 Refugee Convention: The 1951 Geneva Convention is the main international instrument of refugee law. It clearly spells out who refugees are and the kind of legal protection, other assistance, and social rights they should receive from the countries who have signed the document. The convention also defines refugees’ obligations to host governments and defines certain categories of people, such as war criminals, who do not qualify for refugee status. The convention was limited to protecting mainly European refugees in the aftermath of World War II, but another document, the 1967 Protocol, expanded the scope of the convention as the problem of displacement spread around the world.15

Refugee: Refugees are individuals who have been forced to flee their country because of persecution, war, or violence. To be entitled to protection, refugees must have a well-founded fear of persecution on account of their race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group. Such persecution or threats of persecution are often carried out by the government, but they can also be carried out by private actors that the state is unable or unwilling to control. Importantly, refugees frequently cannot return home or are afraid to do so. War and ethnic, tribal, and religious violence are the leading causes of refugees fleeing their countries.

Refugees should receive at least the same rights and basic help as any other foreigner who is a legal resident, including freedom of thought, freedom of movement, and freedom from torture and degrading treatment. Countries may not forcibly return—or refoul—refugees to a territory where they face danger or discriminate between groups of refugees. They should ensure that refugees benefit from economic and social rights, at least to the same degree as other foreign residents of the country of asylum. For humanitarian reasons, states should allow a spouse or dependent children to join persons to whom temporary refuge or asylum has been granted.

Asylum-seeker: When people flee their own country and seek sanctuary in another country, they apply for asylum—the right to be recognized as a refugee and receive legal protection and material assistance. Asylum-seekers are individuals who are seeking to obtain refugee status in the country in which they reside under domestic laws implementing the 1951 Refugee Convention and associated agreements. Asylum-seekers must demonstrate that their fear of persecution in their home country is well-founded. Parties to the 1951 Refugee Convention and the 1967 Protocol are required to give a fair hearing to asylum applications and recognize valid claims to asylum. Governments establish status determination procedures to decide a person’s legal standing and rights in accordance to their own legal systems.

Internally displaced person: Internally displaced persons (IDPs) are individuals who have been forced to flee their home but never cross an international border. These individuals seek safety anywhere they can find it—in nearby towns, schools, settlements, internal camps, and even forests and fields. IDPs, which include people displaced by internal strife and natural disasters, are the largest group that UNHCR assists. Unlike refugees, IDPs are not protected by international law or eligible to receive many types of aid because they are legally under the protection of their own government. Many states and international bodies, however, have acknowledged a set of guiding principles—commonly referred to as the “Deng Principles”—relating to treatment of IDPs.16

Stateless person: A stateless person is someone who is not a citizen of any country. Citizenship is the legal bond between a government and an individual, which allows certain political, economic, social, and other rights to the individual, as well as responsibilities to both the government and the citizen. A person can become stateless due to a variety of reasons, including sovereign, legal, technical, or administrative decisions or oversights. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights underlines that “Everyone has the right to a nationality.”17

Refugees and asylum-seekers by country

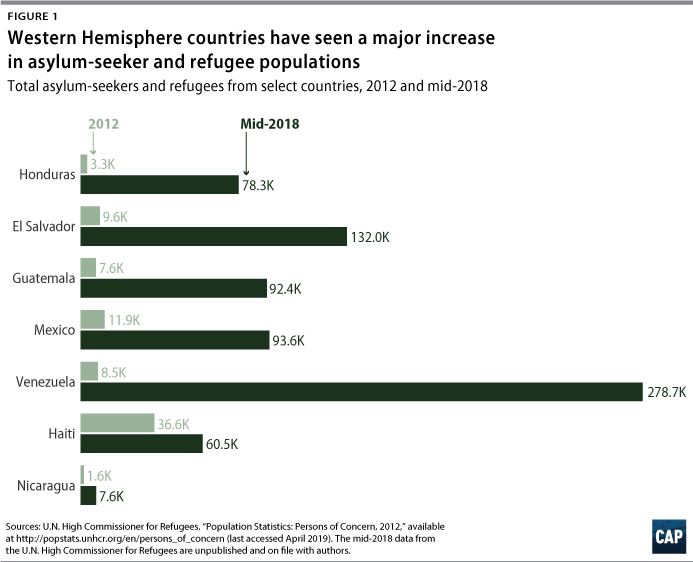

Even as migration flows from Mexico and Central America have shrunk or held steady, the percentage of the migrants who are refugees and asylum-seekers from these countries—and in the Americas as a whole—has grown substantially during the past decade. According to data collected by the UNHCR, there were between 500,000 and 550,000 refugees and asylum-seekers in the Western Hemisphere from 2008 to 2013.18 Starting in 2014, however, that number began to rise, reaching approximately 870,000 in 2017 and exceeding 1 million by mid-2018.19 Although data are not yet available for the end of 2018, the deterioration of the political situation in Venezuela and persistent civil insecurity in some regions of Central America suggest that these numbers have continued to increase markedly during the past 10 months.

For decades, Colombia has produced the largest share of forcibly displaced persons in the Western Hemisphere on account of its brutal and protracted internal armed conflict. However, it saw a decline in the number of refugees and asylum-seekers between 2012 and mid-2018, reflecting the negotiation of a national peace agreement and the broader past-decade trend toward political stability in the country.

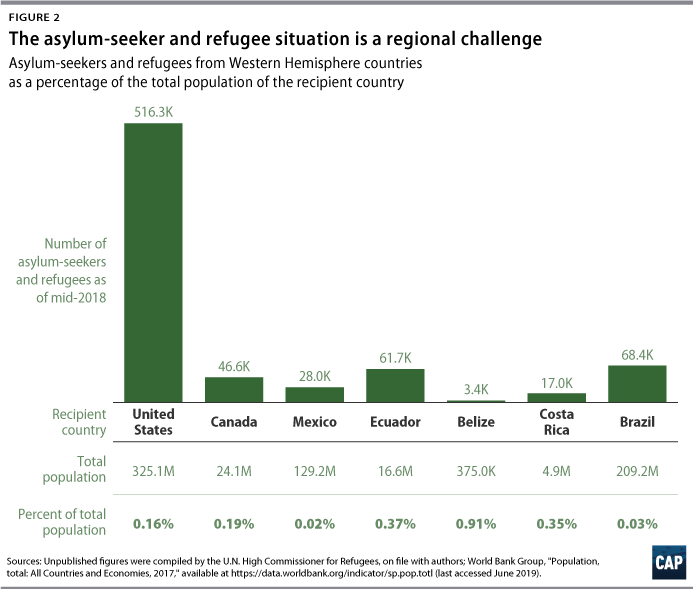

By contrast, the six other major source countries for refugees and asylum-seekers saw sharp increases between 2012 and mid-2018. Honduras saw an approximately 2,128 percent increase in refugees and asylum-seekers, from fewer than 3,500 in 2012 to more than 78,000 in mid-2018.20 Likewise, Guatemalan refugees and asylum-seekers increased from fewer than 8,000 to more than 92,000, and El Salvador from fewer than 10,000 to more than 130,000.21 Venezuela, meanwhile, saw the largest increase in absolute terms, surging from around 8,500 refugees and asylum-seekers in 2012 to more than 278,000 in mid-2018.22 Mexico’s refugee and asylum-seeker population grew eightfold, while Haiti’s increased by around 65 percent—a concerning, but nonetheless modest, increase in comparison with the other major source countries in the region.23 In terms of recipients, the United States has seen the largest influx of asylum-seekers—more than half a million cumulatively as of mid-2018, chiefly from El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Venezuela, Mexico, and Haiti. It is not, however, alone in being a recipient of asylum-seekers across the Americas. The largest groups of asylum-seekers in Brazil and Peru, for example, are Venezuelan nationals, while Mexico hosts substantial numbers of Central Americans and Venezuelans.24

By contrast, the six other major source countries for refugees and asylum-seekers saw sharp increases between 2012 and mid-2018. Honduras saw an approximately 2,128 percent increase in refugees and asylum-seekers, from fewer than 3,500 in 2012 to more than 78,000 in mid-2018.20 Likewise, Guatemalan refugees and asylum-seekers increased from fewer than 8,000 to more than 92,000, and El Salvador from fewer than 10,000 to more than 130,000.21 Venezuela, meanwhile, saw the largest increase in absolute terms, surging from around 8,500 refugees and asylum-seekers in 2012 to more than 278,000 in mid-2018.22 Mexico’s refugee and asylum-seeker population grew eightfold, while Haiti’s increased by around 65 percent—a concerning, but nonetheless modest, increase in comparison with the other major source countries in the region.23 In terms of recipients, the United States has seen the largest influx of asylum-seekers—more than half a million cumulatively as of mid-2018, chiefly from El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Venezuela, Mexico, and Haiti. It is not, however, alone in being a recipient of asylum-seekers across the Americas. The largest groups of asylum-seekers in Brazil and Peru, for example, are Venezuelan nationals, while Mexico hosts substantial numbers of Central Americans and Venezuelans.24

Even accounting for these increases, the total number of refugees and asylum-seekers in the Americas is small relative to historical migration flows. However, because international law requires states to accept refugees within their borders and give a fair hearing to requests for asylum, 25 a significant increase in either of these populations can strain the capacities of domestic immigration systems. In the Americas, the challenge of processing a growing asylum-seeker population has been compounded by the fact that many of those seeking refugee status travel in family units or as unaccompanied minors.26 Along the southern border of the United States, parents and children now comprise nearly two-thirds of Border Patrol apprehensions, up from 10 percent in 2012.27 These changing demographics have tested the response of an immigration system that was designed when the majority of foreign persons seeking to enter the United States without authorization were single adult males, most of whom sought to avoid contact with immigration authorities. The magnitude of the challenge—and the failure of the government’s current response—is highlighted by the fact that multiple children have died in, or shortly after leaving, U.S. Customs and Border Protection’s custody since December 2018, the first such deaths in a decade.28

Other migration patterns

Refugees and asylum-seekers represent only a fraction of the total number of migrants fleeing poverty, violence, and repression in the Americas. Of note, the collapse of the Venezuelan economy under the corruption and incompetence of the Maduro regime has led to a surge in migration from the country. According to the UNHCR, the total number of Venezuelan migrants and refugees worldwide was estimated at 4 million as of May 2019—and could reach 5 million by the end of the year—with an estimated 5,000 migrants arriving in neighboring countries each day.29 The UNHCR has also reported that as of April 2019, more than 414,000 Venezuelans have applied for asylum and formal recognition as refugees since 2014.30 Notably, many Venezuelans leaving their country due to violence, persecution, and extreme economic hardship are not seeking refugee status abroad; they instead view their exodus as temporary, holding out hope that they will return in the near future. In the meantime, many find work in the informal economy of their countries of destination without seeking legal protections. Many recipient countries, including Colombia and Peru, have encouraged Venezuelans to seek temporary residence status under their domestic laws.31

Colombia and Peru have taken in the largest share of Venezuelans. There are now more than 1 million Venezuelans in Colombia, which has allowed virtually unrestricted immigration from its neighbor in reciprocity for the many Colombians who took refuge in Venezuela during the Colombian internal armed conflict.32 If present trends continue, the number of Venezuelans in the country will reach 2 million in 2019 and 4 million by 2021.33 A similar phenomenon has occurred in Peru, Chile, and Ecuador, which host around 1 million Venezuelan nationals between them.34

Colombia, meanwhile, continues to grapple with a population of IDPs that far exceeds other migration in the hemisphere. Notwithstanding the historic 2016 peace agreement and the return of many forcibly displaced Colombians to the country, conflict continues between the government and armed groups in areas previously controlled by the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) insurgency.35 As a result, the number of IDPs in Colombia reached 7.7 million in 2017—the largest population of IDPs in the world, exceeding in absolute terms even those of Syria and Congo.36 The large number of Venezuelans now living in the country has placed additional strain on the Colombian government’s response capacity.

Causes, implications, and responses

The factors driving the increase in refugees, asylum-seekers, and other migrants in the Western Hemisphere do not lend themselves to easy solutions, and there are many plausible scenarios under which they could grow more acute—for example, further deterioration of the political situation in Venezuela, an escalation of civil conflict in Haiti or Nicaragua, or a major natural disaster in Central America or the Caribbean.

Key drivers of migration in the Americas

There is no single, dominant factor—such as a war or a natural catastrophe—driving recent migration patterns in the Americas. Rather, the countries producing the largest share of migrants are all afflicted, to varying degrees, by an interlocking set of political, economic, and social challenges that have given rise to pervasive insecurity and desperation. Although every country’s situation is to some extent unique, these challenges can be grouped into the following four broad categories.

There is no single, dominant factor—such as a war or a natural catastrophe—driving recent migration patterns in the Americas. Rather, the countries producing the largest share of migrants are all afflicted, to varying degrees, by an interlocking set of political, economic, and social challenges that have given rise to pervasive insecurity and desperation. Although every country’s situation is to some extent unique, these challenges can be grouped into the following four broad categories.

Crime and violence

As of 2018, Latin America and the Caribbean had the unwelcome distinction of being the most violent region on the planet, accounting for nearly 40 percent of global homicides despite containing only 8 percent of the world’s population.37 Much of this crime has been concentrated in countries currently experiencing high levels of out-migration. Since 2014, Honduras, Venezuela, and El Salvador have traded places as the country with the world’s highest murder rate, with Mexico and Guatemala not far behind.38 Extortion and kidnappings are also rampant across the region, as is violence against women. Unsurprisingly, this pervasive insecurity has led to large-scale displacement: A recent Doctors Without Borders report found that 40 percent of Northern Triangle asylum-seekers mentioned direct attacks on them or their families as the main reason for their emigration.39 The causes of this crime epidemic are complex, but key factors include entrenched gang rivalries, militarized policing, broken and ineffective justice systems, and lack of lawful employment opportunities.40

Extreme poverty and economic collapse

Although most Western Hemisphere economies have strengthened over the past decade, Venezuela and some areas of the Northern Triangle have seen sharp contractions, with corresponding increases in malnutrition and disease. In Venezuela, corruption and mismanagement have magnified the effects of depressed oil prices and sanctions, leading to the implosion of what was once one of the most prosperous economies in the Western Hemisphere.41 In the Northern Triangle—and in Guatemala especially—drought and crop disease have created an epidemic of hunger in communities that were already living at or near subsistence levels.42 In both cases, sharp deteriorations in quality of life have caused migration across the socio-economic spectrum, from college-educated professionals in Venezuela to women and children from indigenous communities in Guatemala and Honduras.43

Environmental degradation and loss of traditional lifestyles

Closely linked to hunger and poverty as drivers of migration are the disruptive effects of climate change. The agricultural sector accounts for a quarter of employment in the Northern Triangle, and changing weather patterns—in particular drought and irregular rainfall—have increased food insecurity and devastated livelihoods across the region.44 Indigenous communities engaged in traditional farming methods, which already occupy a precarious and marginalized position in Northern Triangle society, have been especially affected.45 In Venezuela, too, drought has aggravated already chronic shortages of water and power, contributing to a precipitous decline in living standards in the country.46

Impunity and elite indifference

A key factor reinforcing and enabling migration drivers in the Americas is the failure of public officials and business leaders to address the entrenched dysfunction and lack of economic opportunity that is causing poor and vulnerable populations to leave.47 A combination of democratic backsliding, deepening corruption and state capture, and weak institutions has meant that national and regional elites in Central America and Mexico are uninterested in and unwilling to invest in social programs, undertake much-needed law and justice reforms, and help communities battered by climate change manage erratic weather patterns and crop failure.48 This pervasive impunity and indifference has sown hopelessness in societies already struggling with staggering violence and high unemployment. The resulting desperation and pessimism have contributed to high migration levels even in countries where levels of violence have improved in recent years—for example, Honduras, where migrant flows have increased even though homicides have dropped significantly since 2016.49

For the foreseeable future, large-scale movement of people in the Americas is likely to be driven by fear and extreme privation, rather than by the search for economic opportunity that characterized earlier waves of migration. The implications of this shift are profound. Migrants fleeing violence and extreme poverty pose unique administrative and logistical challenges for recipient countries and are unlikely to be deterred by threats of aggressive enforcement of immigration laws.50 Without a coordinated, well-resourced framework for managing migrant flows, a future mass migration scenario in the Western Hemisphere could precipitate a major humanitarian crisis and destabilize governments across the region. To date, some regional stakeholders have taken steps to address new migration patterns, but these efforts have not matched the scale of the challenge.

Foreign assistance and migration

In public discussion of mass migration events, foreign assistance is often presented as a tool to mitigate migration pressures. This is certainly the case in the Americas, where a range of public officials and commentators across the region have echoed Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador in proposing a “Marshall Plan” for Central America.51 Under such a proposal, billions of dollars would be invested in development projects aimed at addressing the root causes of migration.52

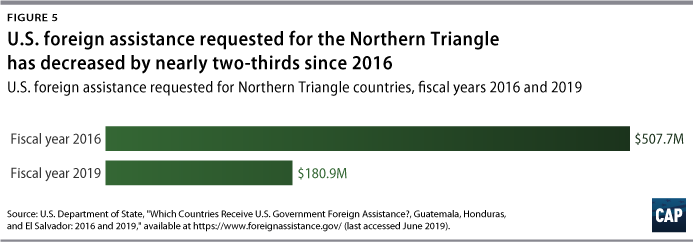

There is little question that the many challenges confronting Central American countries justify a substantial increase in assistance to the region. In fiscal year 2018, the United States spent around $879 million in foreign assistance to Mexico and Central America, or about 3 percent of the total foreign assistance budget for that year.53 FY 2019 budget requests for those countries were considerably lower.54 Such funding levels are not in proportion to the gravity of the economic, political, and social crises afflicting the region, especially when viewed against U.S. commitments in other parts of the world.

At the same time, it is important to recognize the limits of traditional foreign assistance. Implemented correctly, foreign assistance can help rebuild broken societies, strengthen fragile institutions, reduce violence, and improve standards of living. Such transformations do not happen overnight, of course, and they depend critically on the political will and rectitude of local elites as well as the competence of implementing partners. For this reason, some observers have been skeptical about increased investment in the Northern Triangle.55 But even where such positive changes occur, they do not necessarily produce a decrease in migration outflows, at least in the short term.

A recent study of the relationship between migration and foreign assistance examined more than 100 countries over 25 years and found that some forms of aid—specifically those aimed at strengthening governance—did contribute to reduced emigration from recipient countries, whereas other forms focused on economic development or improving social conditions did not affect migration.56 Other investigations of this topic have found that the effect of foreign assistance on migration is, at best, limited and, in some cases, may produce short-term increases in migrant flows.57

These findings do not mean that the United States and other donors should reduce economic and social development projects in regions with high migration levels in favor of more governance interventions. Such investments are justified by their humanitarian benefits and the prosperity and stability they yield over the long term. The uncertain relationship between aid and migration, however, cautions against setting unreasonable expectations about the ability of international actors to solve migration challenges through traditional foreign assistance alone. Such efforts must be paired with well-resourced and coordinated efforts to process and accommodate migrant flows, on the understanding that high levels of migration may continue—and even increase—after a surge in assistance levels. They must also be accompanied by efforts designed to anchor potential migrants in their communities of origin.

Mexico and Central America

The countries of the Northern Triangle remain gripped by extreme levels of violent crime and crushing poverty driven in significant part by broken justice systems, rampant impunity and graft, and lack of economic opportunity.58 Although homicide rates have declined across the region since 2016, violent crime remains endemic and is rarely punished.59 Levels of violence against women are among the highest in the world, and extortion and forced gang recruitment are facts of life for many residents.60

Political actors are often co-opted by—or themselves ringleaders of—organized crime networks and have little incentive to reform government institutions or invest in inclusive economic growth.61 Some of these countries, especially Honduras and Guatemala, are also gripped by democratic backsliding and cultures of impunity.

In 2017, Honduran President Juan Orlando Hernández declared victory following an election marred by grave irregularities and a questionable Supreme Court ruling that allowed him to seek a constitutionally dubious second term.62 Nevertheless, the Trump administration quickly recognized the election results.63 In response to largely peaceful protests, Hernández suspended constitutional rights and imposed a curfew backed by military force.64 Notwithstanding these actions, in late 2017, the U.S. State Department certified that the Honduran government had been making efforts to promote human rights and fight corruption, entitling it to continue to receive U.S. aid.65

In Guatemala, President Jimmy Morales, who campaigned as an uncorrupted political outsider, has sought to hamstring a highly effective and immensely popular anti-corruption commission.66 The United Nations-organized commission, known as the International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG), has received strong bipartisan support from U.S. policymakers and established itself as a major force promoting transparency and accountability. Yet shortly after President Morales expelled the head of CICIG following reports that the commission was investigating corruption in his administration, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo praised Guatemala’s government for its “efforts in counternarcotics and security.”67 U.S. officials have continued to voice support for Morales despite his sustained efforts to shut down CICIG.68

These dire governance challenges have been aggravated by climate change-related drought and a devastating outbreak of coffee rust in Central America last year.69

Beyond the Northern Triangle, an outbreak of political violence in Nicaragua in 2018 has led to hundreds of deaths, a wave of repressive policies by the country’s government, and major economic turmoil.70 This situation has led thousands of Nicaraguans to flee across the border to Costa Rica, overwhelming local officials and triggering xenophobic and even violent reactions from residents.71

Mexico suffers from similar challenges as the Northern Triangle, albeit on a less severe scale. Despite improvements in governance, violence against civilians and the capture of local officials by organized crime remain endemic in some areas of the country, leading many residents to seek refuge in neighboring countries. As of mid-2018, there were approximately 83,000 Mexican asylum-seekers in the United States, a sevenfold increase from 2013.72

In October 2017, Mexico, Guatemala, Costa Rica, Honduras, Panama, and Belize implemented their respective comprehensive refugee response frameworks to address the inbound flows of refugees from the Northern Triangle of Central America.73

Since taking office in December 2018, Mexican President López Obrador has signaled an eagerness to advance the economic development of southern Mexico and the countries of the Northern Triangle. On his first day in office, he signed an agreement with the presidents of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras to foster development and strengthen the rule of law in the Northern Triangle.74 Mexico also announced a near-immediate agreement—albeit one long on rhetoric and short on detail—with the United States to deepen regional cooperation and enhance economic development in southern Mexico and the Northern Triangle countries.75 Most recently, Mexico, in cooperation with the U.N. Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), has presented a development plan for southern Mexico and the Northern Triangle.76 The Trump administration welcomed this plan in a joint declaration that, for now, averted implementation of President Trump’s threatened tariffs against all Mexican imports if Mexico fails to reduce all migration to the United States.77 All of this, of course, has happened against a backdrop in which President Trump ordered a termination of U.S. assistance programs in the Northern Triangle,78 resulting in cancelation of $370 million in budgeted programming for FY 2018 and $180 million for FY 2017 until Northern Triangle countries take some unspecified action to curb migration.79

Central America’s Dry Corridor: A driver fueling migration from the Northern Triangle

Alongside violence, poverty, and political dysfunction, climate disruption in Central America’s Dry Corridor has also become a main factor driving migration from that region. A tropical dry forest region on the Pacific side of Central America that naturally experiences irregular rainfall, the Dry Corridor has become one of the most susceptible regions in the world to climate change-related weather variability since as early as 1960.80 More than 45 million people inhabit the region, many of whom are vulnerable indigenous people living in rural areas. Severe inclement weather has negatively impacted the resilience and economic growth of communities throughout the region and led to significant increases in malnutrition and other negative health outcomes.81

The western highlands of Guatemala have been one of the regions of the Dry Corridor most affected by climate change. In recent years, climate change-related drought has devastated agriculture yields in the region, driving subsistence farmers and their families to abandon traditional ways of life and embark on dangerous and arduous journeys north in search of economic opportunity.82 Of the 94,000 Guatemalan immigrants deported from the United States and Mexico in 2018, approximately half came from the western highlands—a 50 percent increase since 2016.83

A U.S. Agency for International Development-financed pilot program known as the Climate, Nature, and Communities of Guatemala—which launched in 2014 and was canceled by the Trump administration in 2017—showed encouraging results in helping western highlands villagers respond to climate change through crop diversification, water conservation, and reforestation.84 Although the program represented only $190,000 annually out of a total of $200 million in assistance programming to regions with high migration levels, it showed that with adequate and well-targeted resources, migration can be managed responsibly at its source.85

Venezuela

Venezuela’s economic collapse and descent into a corrupt, authoritarian narco-state is one of the great tragedies of modern Latin America.86 Massive declines in basic living standards have led to widespread malnutrition and disease as well as skyrocketing violence.87 The country’s inflation rate surpassed 1 million percent in 2018 and is projected to reach 10 million percent by the end of 2019.88 This sharp deterioration in living conditions, coupled with the increasingly repressive practices of the regime headed by Nicolás Maduro, has sent millions of Venezuelans searching for survival and a better life in neighboring countries.89 In contrast to the Central American asylum-seeker situation, whose duration is uncertain, there is every reason to believe the large-scale exodus of Venezuelans is a protracted crisis that, like the one produced by civil unrest in Colombia in the 1980s and 1990s, will be felt for years, if not for decades.

The large-scale exodus of Venezuelans is a protracted crisis that … will be felt for years, if not for decades.

Further chaos in Venezuela, which is likely in nearly all foreseeable scenarios, could overwhelm the already stressed capacities of neighboring countries and exacerbate existing migration drivers. If factors that determine Venezuela’s foreign income worsen—oil production, price of oil, annual remittance, and foreign aid—it is estimated that the number of forcibly displaced Venezuelans worldwide, including the 4 million already outside the country, could reach 8.2 million in the coming years.90 This level of displacement would surpass even the Syrian refugee crisis and have wide-ranging effects on the political stability of neighboring countries. This includes, above all, Colombia, where the large numbers of Venezuelans entering into unsettled border regions with significant IDP populations and ongoing violence have strained the national government’s capacity to respond to multiple humanitarian challenges.91 But the threat of instability also extends to Peru and the countries of the Caribbean Basin, many of which have struggled to accommodate the sudden influx of Venezuelans into their small territories.92

In September 2018, Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, and Uruguay announced the Declaration of Quito to address the migratory crisis of Venezuelan refugees.93 The declaration sought, among other things, to enhance regional cooperation, including additional international community financial support for countries facing large influxes of Venezuelan migrants, and to provide domestic legal protections for Venezuelan migrants, including access to basic social services and acceptance of expired travel documents as proof of identity. Yet increasing inbound flows of forcibly displaced people have pressured and strained partners in the region to meet the emergency needs and asylum requests of those entering their borders. To date, there has been a significant disconnect between policy and practice among regional governments: Even those that formally accord basic rights and services to Venezuelans are often not able to deliver on those guarantees.94

Governments on the front lines of the Venezuela crisis are also beginning to retreat from their previously liberal policies toward migrants amid backlash from their own citizens. Last summer, Peru and Ecuador imposed a requirement that Venezuelans seeking to enter their countries possess a valid passport, whereas previously, a national ID card was sufficient to obtain entry; this requirement was subsequently struck down in court.95 Earlier this year, after a highly publicized murder of an Ecuadorian woman by her Venezuelan boyfriend sparked xenophobic riots, Ecuador added an additional requirement that Venezuelans present their criminal record to immigration authorities.96 These policies arguably fly in the face of the Cartagena Declaration, a nonbinding legal instrument endorsed by most Latin American countries—and, in many cases, incorporated into their domestic laws—that provides a more expansive definition of refugees than does international law.97

By contrast, Colombia has continued to receive Venezuelans without restriction and has taken extraordinary steps to process and integrate displaced persons within the country despite the immense scale of the challenge.98 However, with the Colombian public increasingly viewing Venezuelan migration as a net negative for the country, it is not clear how much longer the country’s government can sustain this approach.99 Colombia also faces a significant implementation challenge with regard to integrating Venezuelan migrants and refugees, a challenge that is layered upon Colombia’s ongoing struggle to extend the reach of the central government to all of the country’s territory.

Haiti and Cuba

The risk of a mass migration scenario is not limited to Central and South America. Deepening instability in Haiti could lead to thousands of Haitians fleeing to the United States and other neighboring Latin American and Caribbean countries—reminiscent of the wave of Haitian “boat people” that fled to the United States after a military coup ousted Jean-Bertrand Aristide in the early 1990s.100 In the same vein, the Trump administration’s efforts to isolate Cuba and limit travel to the country could strangle the country’s nascent private sector and produce a sharp contraction in its economy.101 Previous eras of heightened tension on the island have led to significant Cuban out-migrations.102 When these scenarios are considered against the likelihood of a climate-related catastrophe equal to or greater than that wrought by Hurricane Maria in 2017, the probability of a major migration event in the Caribbean Basin becomes too great to ignore.

Latin America’s epidemic of gender-based violence

Violence against women is pervasive across Latin America, especially in areas generally afflicted with high levels of violent crime. According to a 2017 United Nations report, the region has the highest level of sexual violence against women committed outside an intimate relationship and the second-highest rate of violence committed by partners or ex-partners.103 The region also contains some of the highest murder rates for women in the world, often linked to gang violence.104

Violence against women has become a primary factor driving migration from the Northern Triangle, especially from El Salvador and Honduras. Both countries consistently rank among those with the highest rates of femicide—that is, the murder of women because they are women.105 El Salvador in particular has seen its rate of femicide double in five years; as of this year, the country experienced one femicide victim every 24 hours and had the highest murder rate of women in Latin America, with most cases having gone unsolved or unprosecuted.106 In addition, gangs in both countries commonly use sexual violence as a tool of intimidation and social control.107 A recent study by the University of Washington found that women migrants from Northern Triangle countries were more likely than men to report violence as a reason for leaving home.108

Recent U.S. policy has undermined efforts to reduce gender-based violence in Latin America and raised obstacles for actual and potential victims of such violence to obtain asylum in the United States. Under President Trump, the United States has reduced funding for programs aimed at combatting violence against women in Central America. In El Salvador, for example, total funding for such programs in 2018 was only $600,000, less than 1 percent of total foreign assistance expenditures for the country.109 At the same time, the administration has sought to disqualify domestic violence as a valid basis for asylum—a policy that, for now, has been blocked in federal court.110

Recent U.S. policy responses to migration in the Americas

For more than four decades, U.S. administrations have, to a greater or lesser extent, grappled with the challenge of managing migration from the Americas. When the increased arrival of unaccompanied minors gained national attention in 2014, the Obama administration initially adopted a near-exclusive “aggressive deterrence” approach to migration management,111 dramatically expanding the detention of families in hastily constructed or converted facilities and reducing opportunities for release from detention.112 In time, this gave way to an approach that additionally involved addressing the root causes of migration by making significant, targeted investments in sustainable economic development and citizen security in the Northern Triangle countries of Central America. It did so directly through $750 million in assistance, primarily to nongovernmental organizations engaged in development and citizen security efforts in the Northern Triangle. Limited amounts of assistance provided directly to Northern Triangle governments were made dependent on the governments engaging in fiscal reforms as well as anti-corruption and transparency efforts.113 It also did so by leveraging multilateral resources, primarily through the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB).114

These efforts suffered from challenges inherent to ramping up such a significant increase in assistance.115 Even so, some of the investments were beginning to bear fruit by the end of the Obama administration—most notably in El Salvador, where U.S. assistance contributed to an improvement in the pervasive insecurity that has been a key driver of migration from that country.116 The primary setback for the approach launched by the Obama administration, however, was the onset of the Trump administration and its nativist, deterrence-only approach to migration in the Americas.

Even before President Trump’s recent impetuous decisions to threaten tariffs on Mexico and cut off assistance to the Northern Triangle in retaliation for their alleged inaction on migration, the administration had decreased and slow-walked regional assistance in all categories except for borders and drug control.117 It shifted its Central America approach to focus less on improving security, governance, and everyday life and more on preventing illegal immigration through tougher enforcement and financing opportunities for U.S. businesses in the form of additional Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC) resources for projects in the Northern Triangle.118 In both Honduras and Guatemala, the administration has made a strategic choice to tolerate democratic backsliding for the sake of security cooperation, a decision questionable on its own terms—corruption and authoritarianism have historically gone hand in hand with the drug trade and organized crime119—but one that is especially misguided in light of the administration’s insistence that both governments must do more to stop migrant flows. In 2017, the Trump administration also ended the Central American Minors (CAM) refugee and parole program created in 2014, which was meant to help stem the flow of unaccompanied children making the dangerous journey to the United States from Northern Triangle countries by offering them a shot at protection from within the region itself.120

More broadly in the Americas, the Trump administration has disillusioned many key partners by disinvesting in diplomacy, foreign assistance, and democracy promotion. The administration has been slow compared with its predecessors to appoint high-ranking U.S. officials focused on Latin America and the Caribbean.121 President Trump has expressed support for President Jair Bolsonaro of Brazil despite his history of xenophobic rhetoric and praise for Brazil’s two-decade period of military dictatorship.122 The administration has also lacked the will to invest in partner capacity or press for a collective response to forcibly displaced people; moreover, it has failed to appropriately plan for contingencies as Venezuela plunges deeper into crisis.

Instead, last November, the Trump administration announced a new ceiling of just 3,000 refugees for FY 2019 from Latin American and Caribbean countries, a number that is not remotely in proportion to the number of refugees generated by the crisis in Venezuela alone.123 The administration’s overall retreat from global refugee resettlement sets a dangerous precedent for other countries around the world, which have thus far not increased their own admissions to make up the difference.124 Furthermore, out of the billions needed, the Trump administration only offered $213 million of humanitarian funding from FY 2017 to FY 2019 for the Venezuela regional crisis response and, in FY 2019, provided only $36.4 million in bilateral assistance to support Colombian efforts to respond to Venezuelan arrivals.125

The Trump administration has chosen to abandon any pretense of compassion toward those fleeing disaster, war, and violence by:

- Demonizing asylum-seekers as dangerous criminals bent on “invasion”126

- Ending the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program and taking steps to subject more than 700,000 DACA recipients—the vast majority from Latin America—to the threat of deportation to countries they left more than a decade ago as children127

- Triggering the termination of Temporary Protected Status (TPS) for hundreds of thousands of Salvadorans, Hondurans, Haitians, and Nicaraguans—thus ignoring in-country consular personnel’s warnings that ending TPS for most of these countries would undermine regional stability, increase irregular migration, and strain U.S. border security efforts128

- Unilaterally rewriting asylum laws to make it harder to achieve protection for persecution related to gang violence and domestic abuse129

- Engaging in abusive and degrading treatment of migrant populations and refugees—including a heinous policy of separating migrant children from their parents and turning back more than 10,000 Central American asylum-seekers, who now must wait in Mexico for months, often in dangerous conditions, in order to have their asylum applications adjudicated at a later date130

In addition, the administration has proposed irresponsible and impractical solutions to the Central America refugee crisis specifically, including:

- The construction of a wall along the U.S. southern border

- The deployment of the U.S. military on an unnecessary and possibly unlawful mission to allegedly protect the border from migrant caravans131

- The decision to implement a “remain in Mexico” strategy that subjects asylum-seekers to violence and abuse in Mexico132

- The recent threat to raise tariffs across the board on all products imported from Mexico until it stops all potential migrants seeking to enter the United States

The cumulative effect of these choices sets a damaging and inhumane example on immigration policy that will give legitimacy to other regional actors seeking to adopt draconian policies toward refugees, asylum-seekers, and other migrant populations. To both advance the national interest and set a strong humanitarian example, the United States must do better.

Recommendations

Migration realities in the Americas require a fundamental reassessment of the U.S. approach. Advancing U.S. national interests requires tackling the drivers of migration in a far more ambitious, concerted, and coordinated manner than has been done to date. This approach cannot come from the United States alone, but the United States can and should lead the efforts. Doing so will required principled, well-resourced, and well-coordinated efforts that actively seek to mitigate migration, enhance partner capacity, and remedy severe U.S. shortcomings that hamper its ability to effectively manage migration in the Americas.

Invest, at scale, in peace and democracy in the Americas

Too often, the United States has lent support to authoritarian and repressive regimes in the Western Hemisphere in the name of great power competition, security cooperation, counternarcotics, or other purportedly strategic goals. In the long term, however, such alignments have contributed to regional instability; failed to advance U.S. interests and values; and contributed to migration drivers, including violence and lack of economic opportunity.

This has been especially true in Central America, where the entrenched poverty and political dysfunction driving the current refugee crisis stem, albeit only in part, from U.S. actions in the region during the Cold War and through to the present day. Yet history has also demonstrated that U.S. investment and democracy promotion in the Americas can profoundly improve the lives of millions.

The following section details the ways in which the United States should use its unparalleled resources to help create conditions that will ease migratory pressures while also advancing other core national interests.

Stand up for democracy, human rights, and the rule of law

The U.S. approach to the Americas, including its approach to managing migration in the Americas, must prioritize support for democracy, human rights, and the rule of law. A proliferation of democratic, inclusive societies that generate across-the-board economic opportunities in the Americas would clearly be in the U.S. national interest. U.S. policy and investments should be geared to promoting those outcomes.

To achieve this objective, it is critical to break the cycles of impunity that hamper development and foster insecurity in countries across the Americas. The United States has long supported the fight against organized crime and graft throughout the Western Hemisphere, admittedly, with differing levels of success. It should maintain its long-held policies of funding police professionalization, supporting judicial reforms and institution building, training lawyers and judges, and assisting investigative efforts into money laundering, extortion, and murder in the region.133 It must robustly support anti-corruption and transparency efforts throughout the region. Doing so not only responds to popular demands throughout the Americas, but also advances core U.S. national interests. The work of CICIG in Guatemala, for example, has been credited with breaking cycles of impunity and strengthening the rule of law as homicide rates have declined in the country.134 Similarly, the Organization of American States-backed Mission to Support the Fight Against Corruption and Impunity in Honduras (MACCIH) has begun the critical work of chipping away at Honduras’ culture of impunity that has long held that country back.135

A proliferation of democratic, inclusive societies that generate across-the-board economic opportunities in the Americas would clearly be in the U.S. national interest.

Bring the full resources of the United States government to bear

A sufficiently ambitious U.S. policy response must not only be principled, it must be a top-tier priority across the entire U.S. government. To be a top-tier priority, the U.S. government must: (1) dedicate sufficient resources to the task; (2) reach well beyond the traditional U.S. foreign assistance toolbox; and (3) ensure effective political leadership.

For years, however, the United States has conducted policy in the Americas on the cheap, especially compared with other parts of the world. From 2000 to 2018, for example, total U.S. security and economic assistance in the Americas was $21.65 billion, constituting 7.53 percent of all such U.S. investment in the world.136 For comparison, in that same period, the United States invested $23.08 billion in Pakistan and $24.76 billion in Egypt.137 The time has come to meaningfully invest in addressing those countries and dynamics that most directly affect day-to-day life in the United States.

But the answer is not simply throwing more money at the problem. The U.S. approach must be comprehensive, coordinated, and creative. The Partnership for Growth (PFG) initiative—which was implemented by the Obama administration in 2011 and 2012 in El Salvador, among other countries, and sought to coordinate all levers of U.S. power to help overcome key obstacles to sustainable economic growth—provides a potential Northern Triangle-wide blueprint for reaching beyond the traditional U.S. foreign assistance tool box.138 That reach is needed to find mechanisms that will anchor potential migrants in their communities of origin, and do so today, not only after generational change in Central American societies. For example, microcrop insurance, specific market supports, and alternative development tied to value chains for subsistence farmers, among other creative approaches, all need to be closely examined as potential avenues for mitigating migration among those communities being adversely affected by coffee rust and drought in Central America’s Dry Corridor.

Even a creative, PFG-like approach, however, requires clear political leadership to overcome bureaucratic inertia. To that end, a PFG-like approach should be bolstered by the designation of a senior-level special coordinator for the Northern Triangle—with a clear mandate from the president—to not only lead the interagency efforts but also work on Northern Triangle refugee and migration issues with Mexico, Central and South American governments, the multilateral financial institutions, the Organization of American States, and the United Nations.

Target investment at the underlying causes of migration in the Northern Triangle

It is not enough to simply undo President Trump’s wrongheaded decision to cut off assistance to the Northern Triangle. U.S. investments must be laser-focused in ways that make a real, immediate difference in people’s lives on the ground. Physical and economic insecurity are significant drivers of migration, particularly from the Northern Triangle. U.S. investments should be focused on counteracting both and should be concentrated in those areas from which migration affecting the United States originates.

Violence reduction programs have been shown to decrease migration; they need to be brought to scale across the Northern Triangle.139 Bringing programs to national and regional scale will only be possible with whole-of-society buy-in throughout the Northern Triangle countries—discussed below—as U.S. resources cannot and should not be expected to address these systemic failures alone. More broadly, citizen security is impossible to achieve without sustainable, broadly shared economic growth. U.S. investments should promote bottom-up economic development.140 This goal requires buy-in and active participation from economic and political elites, who, to date, seem all too comfortable with their compatriots fleeing their country in hopes of a better future elsewhere.

Adverse effects of climate change are already driving migration in the Americas. In addition to returning to the Paris climate accord and changing course at home, direct U.S. assistance in the Americas—be it to Central America or across the climate-vulnerable Caribbean Basin—should invest in sustainable mitigation efforts that will allow people to live out their lives where they are born.141 These efforts could include establishing a regional investment plan for southern Mexico and the Dry Corridor of Central America that pairs climate change mitigation strategies with development assistance.

Focus law enforcement, intelligence, judicial, and sanctions tools against transnational human trafficking organizations

A U.S. approach that prioritizes place-based citizen security and economic development efforts to mitigate migration should not set aside effective, complimentary enforcement efforts. To the contrary, law enforcement, intelligence, and judicial tools need to be used to effectively target human trafficking organizations—in the region as well as their U.S. domestic manifestations—that play a significant role in stoking irregular migration in the Americas.142 Identifying key human traffickers in the Americas and ensuring that they are, at a minimum, denied access to the U.S. financial system, for example, should be a top enforcement priority for the Office of Foreign Asset Control within the U.S. Department of the Treasury. Law enforcement and intelligence assets, as well as partner services, in the region should be leveraged to better understand trafficking networks and expose their vulnerabilities.

Reinforce migration mitigation goals in domestic policy decisions

Given physical proximity, the connection between the United States and the rest of the Americas is unique. That proximity creates both opportunities and responsibilities. One such responsibility is to ensure that U.S. gun policy does not continue to aggravate violence in the nation’s closest neighbors, adding to migratory pressure. As the Center for American Progress has previously noted, from 2014 to 2016, “U.S.-sourced guns were used to commit crimes in nearby countries approximately once every 31 minutes.”143 As previously recommended, there are concrete steps that the United States should take to curb the flow of weapons to its neighbors.144

Address the Venezuelan migration crisis

Venezuela presents a particularly complex challenge, as the root cause of mass emigration from the country is the Maduro regime and its catastrophic impact on daily life for millions of Venezuelans. To halt large-scale migration from this country of still more than 30 million people, a peaceful, democratic transition away from Maduro and his corrupt cohort will be essential. Given the magnitude of the economic destruction, however, it is unlikely that large-scale migration will dissipate any time soon.

In short, Venezuelan migration is a reality, and one that will almost certainly intensify in the coming months and perhaps years, regardless of political outcomes. As a result, while the United States works to promote a peaceful, diplomatic transition back to democracy in Venezuela, it must take steps to address the Venezuelan migration crisis as such. Neither the United States nor the region can afford to pretend that the Venezuelan migration crisis is a quickly passing phenomenon. It is past time to mitigate its effect on other countries in the region and on the Venezuelan people.

To those ends, the United States should take the following steps with regards to Venezuela.

Grant Temporary Protected Status to Venezuelan nationals

As CAP detailed in an earlier report on the political and humanitarian crisis in Venezuela,145 the United States has been deporting Venezuelan nationals at the same time as it has been rightly denouncing the repressive actions of the Maduro regime and lamenting the severe economic hardship experienced by ordinary Venezuelans.146 The U.S. Department of Homeland Security must halt these deportations immediately and grant TPS to Venezuelan nationals in the United States, providing them the opportunity to work to send critically needed financial support to desperate family members back home and providing efforts by the United States and regional partners time to gain traction. Failing action from the executive branch, Congress should pass legislation granting TPS to Venezuelan nationals currently in the United States. On May 22, the House Judiciary Committee voted on party lines to advance H.R. 549, a bipartisan measure to grant TPS to Venezuelan nationals in the United States on the date of enactment.147

Expand refugee opportunities for Venezuelans

The president should also revise the current refugee admission cap upward while taking additional long-overdue steps to facilitate the granting of refugee status to Venezuelans fleeing violence and repression at home.148

Support regional migration management efforts

From FY 2017 to date, the United States has offered approximately $213 million of humanitarian funding for the Venezuela regional response; from FY 2018 to FY 2019, it has provided $89.9 million in bilateral assistance to support Colombian efforts to respond to Venezuelan arrivals, and recently, Secretary Pompeo pledged $20 million in additional humanitarian assistance to the people of Venezuela.149 The World Bank estimates, however, that Venezuelan migration to Colombia is costing that country approximately 0.5 percent of gross domestic product, or approximately $16.8 billion per year.150 The United States must do more directly and indirectly—through the United Nations and other effective multilateral mechanisms—to enhance the absorption capacity of Venezuela’s neighbors in the face of growing migratory flows.

Work with Venezuela’s neighbors to develop a contingency plan for refugee flows

As dire as the political and economic situation in Venezuela is presently, even greater political and economic turmoil in the country is likely, even in scenarios in which democracy is restored. The collapse of the Maduro regime or an outbreak of armed conflict could lead Venezuelans to flee in even larger numbers, putting unbearable strain on neighboring states that already shoulder significant burdens, such as Colombia, Peru, and Ecuador. The United States, together with the United Nations and the Organization of American States, should engage in appropriate contingency planning with Central and South American governments—including those that have not, to date, accepted a sizable number of Venezuelans relative to their populations—to avert the humanitarian crises and broader regional destabilization that could accompany further implosion of the Venezuelan state. All actors must also prepare to deal with the lasting effects of Venezuelan displacement even after Venezuela begins its long road to recovery as a functioning democracy and economy.

Establish and fund a multilateral construction and humanitarian relief fund for Venezuela

Venezuelans, even factions within the Maduro regime, need to have hope that a better future awaits them. Without it, Venezuelans in the country likely will not generate the kind of internal pressure needed to complement external pressures and effect real change. Without hope for a better future, more Venezuelans are also likely to flee their country. To foster that hope, the United States should work with its international partners to develop a funding mechanism for nonpoliticized reconstruction and humanitarian relief in Venezuela to stoke confidence and eliminate any dangerous lags in assistance when change comes.151 While several “day after” planning processes exist,152 they need to be made more real by incorporating ongoing humanitarian relief efforts and establishing seed funding for the reconstruction fund. One potential funding mechanism for both purposes that should be examined is the redirection of frozen Venezuelan financial assets to apolitical multilateral relief and reconstruction efforts to make clear that those funds will be dedicated to the sole benefit of the Venezuelan people.

Enhance regional capabilities

The United States should use its diplomatic clout to support the efforts of regional stakeholders to address challenges generated by mass dislocations of people across the Americas. Using that clout does not mean, as the Trump administration has sought to do, extorting Mexico with threatened tariffs or impetuously cutting off aid to the Northern Triangle. Instead, Washington should encourage countries on the front lines of migration crises to develop common frameworks for accepting and processing vulnerable populations. To do so, in addition to putting its own house in order, the United States should take the following steps.

Coordinate efforts on a regionwide basis with capable partners

In response to the 2014 unaccompanied minors’ crisis, the United States worked with the countries of the Northern Triangle and the IDB to support integrated efforts to accelerate and sustain broad-based economic growth in the Northern Triangle.153 With the Mexican government now focused on similar objectives, the United States has an opportunity to further share the responsibility in promoting the kinds of growth and development in southern Mexico and the Northern Triangle that will alleviate migratory pressure. The United States should identify the portions of the recently produced ECLAC plan for integrated development in southern Mexico and the Northern Triangle that would benefit most from U.S. investment. Once it has made that determination, the United States should incorporate such investments into its foreign assistance planning process for the region.

The effort, however, can neither be an expansion of a deterrence-only approach that simply seeks to enlist Mexico and others into those deterrence efforts, nor can it be what the Trump administration has announced to date—an effort that relies too heavily on private sector, large-scale, infrastructure investment and is unlikely to move the needle on community-level economic development.154 This effort, of course, cannot include erratic moves to cut off investment in the Northern Triangle countries or to impose tariffs on all imports from Mexico.

Increased regional coordination and, especially, stepped-up IDB participation can also help overcome the inherent coordination and continuity challenges created by working across three countries—four if Mexico is more effectively incorporated—with different political calendars. Moreover, they can help mitigate a tendency among Central American countries to publicly invoke a regional approach while privately clinging zealously to their distinct bilateral relationship with the United States. To achieve this end, the IDB must also more aggressively embrace its economic development mission.

Similarly, managing the Venezuelan mass displacement requires an integrated response, one that draws in countries from across the Americas, as well as multilateral organizations and private sector and civil society actors in all affected countries. To date, the United Nation’s Regional Inter-Agency Coordination Platform for Refugees and Migrants from Venezuela, coupled with the efforts of the UNHCR and the United Nation’s International Organization for Migration (IOM), has played an important role in pulling together a coordinated response. Its ongoing efforts should be a focal point for hemispheric and global cooperation.

Enlist Central America’s private and civic sectors with the task of building sustainable societies

No amount of U.S. or international assistance can address the underlying causes of migration absent a whole-of-society commitment in the Northern Triangle—or any other affected country—to building sustainable societies from which individuals are not forced to migrate. To that end, the United States must also rekindle efforts to encourage private sector leaders in the Northern Triangle to be part of the solution, rather than part of the problem afflicting those societies, as they have been to date.155 Among the policy tools that need to be deployed are programs that condition U.S. investment to matching investments from private sector actors in the Northern Triangle. The United States also must not be afraid to bar members of the Northern Triangle private sector—and their families—from entering the country if they are engaged in corrupt practices that undermine sustainable economic development.

In addition, the United States, working with partner governments, must champion close collaboration with civil society and community-based groups. Part of building sustainable societies is fashioning a resilient social fabric, something the countries of the Northern Triangle in particular lack at this time. U.S. policy can be a catalyst for knitting that social fabric.

Invest in the capacity of regional actors to process refugee flows in conjunction with the UNHCR

The United States should immediately meet the UNHCR’s identified funding needs—with additional funding from other capable partners, such as Canada and the European Union. Washington should also seek ways to leverage international financial institutions to share the responsibility of providing support to key partners in the region—especially to Mexico and Colombia—as they work to accommodate record numbers of refugees and other forcibly displaced people.156

Encourage countries with inadequate migration frameworks to make appropriate reforms

Although there has been some coordination on migration issues among Latin American governments, several of the most influential and important actors in the Americas—sadly, including the United States under President Trump—maintain inadequate, exclusionary, and, in some cases, punitive approaches to refugees and asylum-seekers. As South America in particular experiences a “turn to the right” in response to the failures of left-leaning governments to control corruption and deliver economic growth, right-wing politicians have seized on migration as a potent political talking point—most notably in Brazil, Chile, and Argentina.157 To avoid a regional race to the bottom on migration issues, the United States should seek to work with the Organization of American States and key stakeholders to develop a joint approach to migration that avoids any one country shouldering a disproportionate burden.

In addition, Washington should pressure Brazil—which lacks a centralized bureaucratic mechanism for receiving migrants, creating huge backlogs in asylum cases158—and the Bolsonaro administration to reform their approach to migration and provide adequate funding to agencies responsible for enforcing immigration laws. Brazil can and should share more of the migration management burden in the Americas. Similarly, Mexico’s key government agencies handling migration lack adequate resources.159 As the United States remedies its own shortcomings, it should similarly urge Mexico to provide real support to its migration, refugee, and asylum processes and agencies.

Adopt a humane and effective approach to immigration and border management to restore respect for the rule of law in the U.S. system

The United States will be unable to drive a regional consensus on migration if its own approach to immigration remains cruel, inflammatory, and ineffective. To show the necessary moral leadership to advance U.S. interests in managing migration in the Americas, the United States should, at a minimum, take the following steps.

End the incendiary and xenophobic rhetoric around asylum-seekers and immigrants generally and commit to building an immigration system that truly works

The dangerous, anti-immigrant rhetoric now coming from the White House is only making it harder for policymakers to tackle the long-overdue reforms to U.S. immigration laws that are needed to maximize the many positive benefits of immigration and restore respect for the rule of law in the immigration system. The United States’ overarching goal should be to build an immigration system that reflects the reality that America has long been—and will continue to be—both a nation of immigrants and a nation of laws. And one basic element of such a system should be a recognition of the basic human rights of those seeking entry to the United States.160

The United States will be unable to drive a regional consensus on migration if its own approach to immigration remains cruel, inflammatory, and ineffective.

Some of the key elements of an approach that recognizes the dignity of migrants and is designed to function effectively would be to:

- Design a legal immigration system that provides realistic, evidence-based, and sufficiently flexible avenues for migration

- Reform immigration enforcement to preserve due process and achieve fair and just outcomes

- Restore the integrity of the U.S. asylum system by ending the “remain in Mexico” policy and other asylum bans and by overturning short-sighted rulings issued by the current and former attorney general that limit who can receive asylum and when asylum-seekers in detention may be entitled to a simple bond hearing before an immigration judge

- Stop sending troops to the U.S. southern border

Fashion a modern refugee program

The overall cap on refugees accepted into the United States on an annual basis should return to at least 110,000 slots, with a specific increase in the number of slots available for refugee from the Americas. A sensible refugee program should also include a regional refugee processing element akin to the Obama-era CAM program.

Restore protections for TPS holders