The geopolitical landscape that emerged after the end of the Cold War is facing recent strains from an unprecedented wave of global migration, climate change, and a more assertive Russia and competitive China—and the Middle East has emerged as a focal point for many of these challenges.

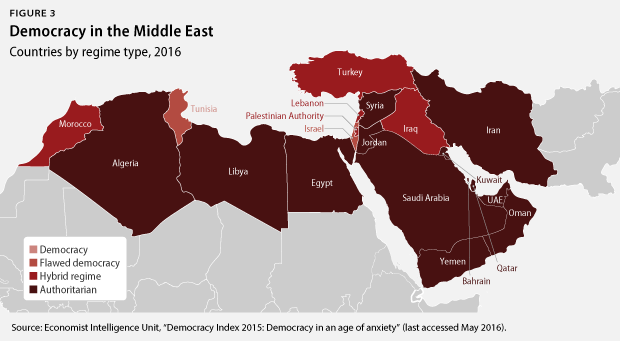

The administration of the next U.S. president will face a Middle East challenged by regional power tensions; multiple civil wars; state collapse driven by political legitimacy crises; threats from rapidly evolving terrorist networks; record numbers of refugees; and escalating economic and human development pressures. These challenges, along with a new wave of regressive authoritarian forces limiting basic freedoms, will require the next administration to take a proactive and long-term approach to the Middle East.

Dynamics in the Middle East have understandably caused many Americans to question the value of U.S involvement in the region. Indeed, this skepticism is supported by the track record of the past 15 years, particularly the fallout from the 2003 Iraq war. But recent events and trends in the Middle East—from the rise of the Islamic State to the refugee crisis spilling over into Europe—demonstrate that the United States has important stakes in what happens in the region. Because of the threats that the Middle East presents for the homeland and the danger that continued conflict in the region poses to global stability, the United States needs to work closely with regional partners to adopt a long-term approach to the region that advances America’s interests and values.

Strategic priorities

Given the civil wars and counterterrorism challenges in the region, the next administration could find itself stuck in a cycle of reaction without a set of clear long-term strategic priorities to guide it. Going forward, the United States should shift away from a crisis management paradigm toward one of renewed American leadership in the region that seeks to more effectively integrate its stepped-up military engagement with diplomatic and economic engagement. The problems of the region require a long-term approach and policy planning should shift toward working with partners to outline an affirmative agenda for the next decade and should look to what can be done not simply in one presidential administration. To this end, the next president should affirmatively set the following first-term and long-term strategic priorities for U.S. Middle East policy.

First-term action items

- Build on the Obama administration’s campaign to defeat the Islamic State and Al Qaeda militarily by deepening multilateral cooperation with regional partners and taking steps to help create a regional security framework.

- Be prepared to use airpower to protect U.S. partners and civilians in certain parts of Syria.

- Conduct intensified diplomatic outreach with long-standing regional partners, with the goal of organizing a regional conference by early 2018 on a shared long-term vision for the Middle East.

- Proactively counter Iran’s negative influence and ensure nuclear deal compliance.

- Use leverage with regional partners to de-escalate internal conflicts.

- Work with global partners to create international compacts to support the growth of legitimate and effective governments and societies in the region.

Long-term initiatives

- Renew U.S. engagement on pluralism, values, and universal human rights, with a focus on the future generations.

- Recalibrate U.S. security assistance and cooperation to foster greater regional security cooperation and integration.

- Focus economic statecraft and engagement to encourage inclusive growth and regional economic cooperation.

The Middle East in 2025

With a more proactive and forward-looking approach, the next president can help partners in the region achieve the following outcomes by 2025:

- Defeat the Islamic State and Al Qaeda affiliates militarily across the region.

- Resolve conflict and make progress toward the creation of new, inclusive, and stable political orders in Iraq, Libya, Syria, and Yemen.

- Reinforce the legitimacy of the region’s nation-state system.

- Prevent the spread of weapons of mass destruction, including the continued effective and verified implementation of the Iran nuclear agreement.

- Begin the process of building a new Middle East regional security framework focused on both security and prosperity.

- Achieve a two-state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, reinforced by broader Arab-Israeli peace and normalization along the lines of the Arab Peace Initiative.

- Support economic reforms to provide decent jobs to the region’s rising generation.

A long-term approach also would help in crafting a more affirmative agenda. Bad news from the region too often obscures opportunities for progress. Despite its current problems, the Middle East can draw on important developments and potential assets, including youthful populations working for positive social change and the fact that some countries in the region are taking steps to change outdated political and economic models. These assets represent a silver lining in an otherwise gloomy regional picture. Yet the Middle East will need targeted engagement from the United States to make good on this potential.

A new U.S. administration brings with it an opportunity to consider once again a longer time horizon in the Middle East. The roiling dynamics of the region—both the long-standing crisis of political legitimacy and the massive societal renegotiations and rebuilding projects that lie ahead—highlight the need for a forward-looking vision that moves beyond the crisis response mode that has overcome U.S. policy over the past 15 years.

Recent events, particularly the rise of the Islamic State, have prompted the Obama administration in its second term to increase its investments in partnerships, particularly on the military front. The U.S. military has adopted an approach of working by, with, and through partners in the region—the correct formula for ensuring burden sharing and preventing a return to when the United States had hundreds of thousands of troops exposed in open-ended wars. But the current approach is incomplete because it lacks a discernable long-term strategic framework. The effort to reinvigorate military partnerships requires similar efforts to build long-term diplomatic and economic partnerships.

In particular, the next administration needs to address a two-way trust deficit that has emerged with some of the closest American partners in the Middle East over the past 15 years. This trust deficit emerged for a variety of reasons, most notably the 2003 Iraq war and its destabilizing effects across the region. In addition, the demographic, economic, social, and political pressures within many countries of the region created a more complicated landscape for U.S. engagement. In recent years, however, traditional partners have cited numerous complaints: the varying U.S. responses to the 2011 Arab uprisings; differences over the role of and response to political Islam; the U.S. posture on Syria’s civil war; and concerns that the 2015 Iran nuclear deal was an attempt to build a new partnership with Iran. In addition, the Obama administration’s effort to rebalance its overall focus to other regions of the world, such as Asia, created a mistaken impression in key parts of the Middle East that the United States was poised to fully disengage from the region.

For the United States, this two-way trust deficit emerged and grew in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks in America. In recent years, the domestic political practices of some regional partners, ongoing explicit or implicit support by some regional partners for extremist interpretations of Islam, and humanitarian consequences of recent conflicts have led some Americans to question the value of these long-standing relationships.

To make progress, the next U.S. administration should seek to recalibrate American engagement in the region. There must be a renewed emphasis on strengthening cooperation with long-standing partners, more engagement with the region’s next generation, and an increased effort to build positive incentives to support political legitimacy and economic and social reform. Doing these three things at once will be difficult but can be achieved if the United States clearly states its long-term commitments and goals in the region.

The next U.S. administration should aim to shift America’s primary security role in the Middle East from that of a security guarantor to that of a strategic integrator—helping integrate and upgrade the capacities of regional partners on all elements of human security. At a time of regional fragmentation, the United States can play an important role in building partnerships on the security, diplomatic, and economic fronts that work to prevent the continued breakdown of the regional state system. Even as the United States continues to honor long-standing security commitments, it is essential that countries of the region—those capable of doing so—find constructive ways to work together to carry a greater share of the burden for building security, prosperity, peace, and respect for basic human dignity. Such are the region’s challenges today that actors both inside and outside the region need to do more to further their self-interest in a more stable future.

The next U.S. administration should work with both the people of the region and its most reliable and capable governmental and private-sector partners to strike a new deal with the Middle East—one that establishes a new basis for U.S. engagement that moves beyond the model of the past 40 years. The next U.S. president should redefine America’s leadership role to address strategic priorities and help constructive and forward-looking actors across the region channel their energy and resources to address the region’s core drivers of instability. The fact that several key countries in the region are putting forward long-term visions for reforming their economies provides new opportunities to encourage and support responsive and more inclusive governance.

Why the Middle East matters to the United States

The Middle East continues to matter for the United States in three main ways:

- Security—protecting homeland security and defending allies. The United States retains a paramount security interest in defending itself, its worldwide allies, and its regional partners against terrorist threats originating in the Middle East. This region is geographically at the epicenter of a broader area that has sometimes been called the “arc of crisis” that includes countries such as Afghanistan and Pakistan. The spread of the Islamic State around the world and the historic recent wave of refugees demonstrate that conflict within the region continues to have a significant impact on security beyond the Middle East, particularly for American allies in Europe. As bad as certain security dynamics within the region are today, it would be a mistake to assume that they cannot deteriorate further and provide greater freedom of action for unpredictable terrorist networks. The United States must remain vigilant regarding various scenarios, including the prospect that interlocking proxy conflicts in Syria devolve into outright interstate war and tensions between key regional powers escalate into direct military confrontation.

- Economic opportunity—safeguarding America’s global economic interests. Despite the rise of renewable energy and the emergence of new oil and gas producers—including the United States—the Middle East’s energy remains critical to the global economy. The Strait of Hormuz, Bab al-Mandab, and the Suez Canal are all key chokepoints through which global trade passes.

Moreover, the Middle East has long served as a vital land and sea transit point for global trade and commerce, and it continues to play this role today in connecting Asia, Africa, and Europe. And even with its current problems, the region has significant potential for long-term economic growth. Several wealthy countries in the Gulf region, for example, are moving to diversify their economies, and this could create new potential for economic growth and foreign direct investment. While the past 15 years have made clear that the task of nation building belongs to the leaders and people of the region, the United States has unique expertise and resources to offer that do not equal sending large numbers of troops to the region or spending untold billions of dollars in U.S. taxpayers’ money. Indeed, economic statecraft represents one important way the United States and its international partners can demonstrate leadership in the Middle East and make a real and positive difference in regional societies. (see Figure 1 in the PDF for the Middle East’s share of global oil reserves in 2015)

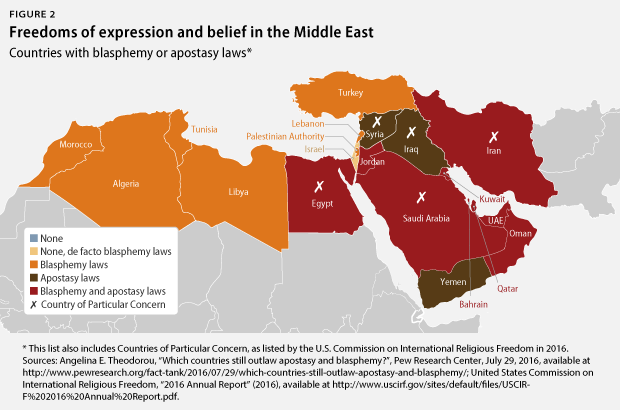

- Values—the battle for basic human dignity and freedom against extremism. From refugee camps and cities ravaged by civil war to protest squares and overflowing prisons, the societies of the Middle East have been on the front lines of the worldwide struggle for human dignity and universal rights—and religious freedom, women’s rights, and gender equality remain a core challenge for basic human dignity in the region. While the path to achieving these rights has proven difficult, America possesses an abiding interest in the worldwide preservation and extension of the universal values embodied in President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Four Freedoms: freedom of expression; freedom of belief; freedom from want; and freedom from fear.

Nowhere else in the world are each of these “essential human freedoms” contested more strongly than in the Middle East. And in no other region does the outcome of that contest have a more immediate impact on U.S. security, as seen in the brutality of the Assad regime against its own people in Syria and in the fight against extremist groups that aim to recreate an imaginary thousand-year-old society in the present day.

The Middle East is embroiled in a fierce contest of ideas at the intersection of religion, politics, and violence—a struggle that manifests differently in different places but affects the entire region. While humility is warranted regarding America’s role and capacity to dictate outcomes, this does not mean that the United States lacks the ability to influence the results. Nor is America neutral regarding the outcome. Beyond the narrow confines of violent extremism where U.S. interests are most acute, the United States has a profound stake in the emergence of political and religious pluralism; greater openness; equality for women; and respect for universal human rights regardless of ethnicity, religion, or sexual orientation.

Almost a decade and a half ago, these basic freedoms were the subject of a series of prescient Arab Human Development Reports that clearly identified that the region faced four profound deficits which if left unaddressed would result in rebellions and instability: the deficits of knowledge; freedom; women’s rights; and economic opportunity. These were indicators for what led to the Arab uprisings, and they will continue to lead to instability in the region if left unaddressed.

The playbook outlined here will allow the United States to pursue its strategic priorities in the region, protecting its enduring interests and pragmatically advancing its values along the way. Moreover, this approach would work to encourage governments and societies across the region to take responsibility for their own futures. The United States can encourage and help the people and countries of the Middle East head toward a path of progress, but it will be up to the people of the region to actually walk that path.

Brian Katulis is a Senior Fellow at the Center for American Progress. Peter Juul is a Policy Analyst with the National Security and International Policy team at the Center. Rudy deLeon is a Senior Fellow with the National Security and International Policy team at the Center. Dan Benaim is a Senior Fellow at the Center. Hardin Lang is a Senior Fellow at the Center. Muath Al Wari is a Senior Policy Analyst with the National Security and International Policy team at the Center. William Danvers is a Senior Fellow at the Center. Trevor Sutton is a Fellow on the National Security and International Policy team at the Center. William Wechsler is a Senior Fellow at the Center. Alia Awadallah is a Research Associate with the Middle East team on the National Security and International Policy team at the Center.