Turkey will hold a crucial general election on June 7. The Justice and Development Party, or AKP, faces the first real threat to its single-party control over the Grand National Assembly in its 13 years ruling the country. For the first time since the Republic of Turkey’s formation, a Kurdish political party could enter parliament in force. This could seriously complicate the AKP’s path to a parliamentary majority but might also bring hope for a final resolution of Turkey’s long struggle to peacefully integrate its Kurdish minority. The vote is also likely to decide if Turkey will continue to be dominated by President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, whose personal ambition to build a stronger presidency and solidify his hold on power has shaped the campaign. And the election result could see the ongoing Kurdish peace process derailed by a surge in support for the far-right Nationalist Movement Party, or MHP. Additionally, clashes between Kurds and state security forces in the wake of the vote could derail election results, particularly if electoral fraud is suspected.

The outcome of the election—possibly the last until 2019—may determine the future of the Turkish Constitution of 1982, the political status of the Kurds in Turkey, the position of religion in the public square, the quality of Turkish democracy, and Ankara’s role in the region. A fourth successive outright majority for the AKP would bring four more years of more conservative and religious politics, efforts to rewrite the constitution, a continuation of Turkey’s more independent and active foreign policy, and, possibly, a halt in the work to secure a lasting peace with Kurdish rebels in the country’s southeast. While it may bring stability, an outright AKP win would also likely mean further anti-Western rhetoric and more pressure on political dissent and freedom of expression at home. However, if the AKP is forced into a coalition, the most likely outcome is a pairing with the ultranationalists; this could lead to political instability, an ambivalent line toward the United States and Europe, deep hostility toward the Kurds, and possibly renewed fighting with Kurdish rebels. If the opposition parties are able to record large enough gains to cobble together a government—unlikely as that remains—Turkey’s domestic politics and regional course would dramatically change. Depending on the composition of such a coalition, this outcome might bring a renewed push for EU membership, an easing of pressure on journalists and political activists, and a more restrained regional role. This brief will introduce the key players in this electoral drama, outline the constitutional and political stakes, and analyze potential electoral outcomes and the likely fallout from each scenario.

The parties

Justice and Development Party

The AKP is Turkey’s ruling conservative Islamist political party, which currently holds 312 of the 550 seats in parliament. Formed in 2001 by a moderate faction of the Islamist Virtue Party led by the likes of former President Abdullah Gül, current President Erdoğan, and current Deputy Prime Minister Bülent Arınç, the AKP enjoys the support of Turkey’s conservative, religious lower and middle classes and much of the commercial class. Its electoral base is the rural Anatolian heartland, including Ankara, and the Black Sea coastline; however, it is competitive nationwide, particularly in southeastern Turkey, where it runs a close second to the majority-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party, or HDP, in most constituencies.

Since its founding, the AKP has been dominated by President Erdoğan, who won the presidency with 52 percent of the vote in August 2014. Traditionally, Erdoğan’s election as president would have led him to step back from active politics; under the Turkish Constitution, presidents are supposed to sever all connections with their previous party and have traditionally refrained from political campaigning and electioneering. Erdoğan handpicked then-Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu as his successor as prime minister and head of the AKP but has himself remained the de facto leader of the party, campaigning vigorously on behalf of the AKP.

President Erdoğan’s chief goal is to reform the Turkish Constitution of 1982, written under military rule, in order to take Turkey from its current parliamentary system to a presidential system. Erdoğan argues the change would allow more efficient government and stronger economic growth, but the shift would also further solidify his personal control of the country by providing new powers and a constitutional foundation for his continued political activities. The AKP is heavily tied to the presidential initiative due to Erdoğan’s personal dominance of the party, despite the unpopularity of the proposed changes. But the party faces new political threats, primarily from a spirited Kurdish and liberal challenge from the HDP and anemic economic growth.

The AKP’s primary election goals are to prevent the entry of the mainly Kurdish HDP into parliament, which would threaten AKP’s single-party rule, and to garner at least 330 seats, allowing an AKP government to propose changes to the Turkish Constitution and put them to a national referendum. The AKP’s platform focuses on reviving Turkey’s economy, which slowed to just 2.9 percent growth in 2014. According to Prime Minister Davutoğlu, the AKP is aiming for 50 percent to 55 percent of the vote and has no plans to form a coalition government in the event of party losses. A more realistic goal for the AKP is probably 45 percent of the vote, based on recent polls. Any result below 40 percent would be considered a failure for the AKP and Davutoğlu, potentially prompting a shake-up of the party leadership.

Republican People’s Party

The Republican People’s Party, or CHP, is Turkey’s main opposition party; it is center left, secular, and strongest in western Turkey, particularly along the Aegean coast and in the cities of Edirne and İzmir. The party’s base is composed of highly educated and wealthy Turks, urban liberals, Alevis, the remnants of the old nationalist elite, and socialists. Led by Chairman Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, the CHP has worked to emulate the social democratic parties of Europe. CHP’s goal is to win enough of the vote to create a minority coalition government with either the Kurdish HDP or the nationalist MHP; for the CHP, 30 percent is an ambitious goal that would likely provide the party with paths to a coalition government, but achieving this goal remains unlikely. However, both potential coalition partners are problematic: HDP’s desire for autonomy or federalism is anathema to the CHP’s old guard, which has been weakened but remains strong enough to make a coalition difficult. Meanwhile, the nationalist MHP’s base is far to the right of the CHP, and its foreign policy contrasts starkly with that of the CHP—for example, the CHP is committed to membership in the European Union and a close relationship with the United States, while the MHP opposes EU accession and is ambivalent toward the United States. It should be noted, however, that the MHP did join a coalition with another center-left party, the late Bülent Ecevit’s Democratic Left Party, in 1999, so there is historical precedent for such a partnership. The ambitious election manifesto outlined by CHP Chairman Kılıçdaroğlu touts comprehensive economic reform, including raising the minimum wage to 1,500 Turkish liras, or about $575, per month. The CHP has also pledged to appoint Kemal Derviş as deputy prime minister in charge of the economy; Derviş is widely considered to have been the architect of Turkey’s recovery plan following its economic collapse in 2001.

Nationalist Movement Party

The MHP is Turkey’s far-right party and has a traditional, nationalist constituency similar to that of the AKP, although it generally abstains from religion-based politics and rhetoric. The MHP aspires to win 20 percent of the vote and, possibly, enter a coalition government. Though it would be a long shot, the MHP would likely prefer to form a minority coalition government with the CHP. Such a coalition would probably still need support from the outside, presumably the HDP. The MHP’s ultranationalism and hostility to any form of Kurdish autonomy complicates that equation, however, as the party would almost certainly refuse to enter any coalition including the HDP. This MHP animosity means that despite the fact that the MHP, CHP, and HDP share a dislike for Erdoğan and have a chance to collectively constitute a majority of parliament, such a coalition remains unlikely. Still, if the AKP fails to get a majority and the HDP makes the threshold, the MHP could be the swing party in determining whether the AKP or the CHP leads the next government.

Unlike the CHP, the MHP’s election manifesto emphasizes issues of national sovereignty and foreign policy. According to party leader Devlet Bahçeli, the MHP wants two separate governments in Cyprus—the Republic of Cyprus in the south and the Turkish Republic in the north—a long-term point of tension with Europe and an intentional roadblock to EU membership. The MHP also disagrees with the AKP’s open door policy for Syrian refugees. Bahçeli said as early as 2012 that “Incoming refugees are now up to a point that Turkey cannot handle it anymore.” The refugee situation has dramatically worsened since then. Bahçeli and his party have called for a stricter policy at the border and, with the CHP, argue that some refugees should be returned to Syria. The AKP has also called for the repatriation of Syrian refugees but has done so within the context of proposed safe zones inside Syria, a proposal that the opposition parties oppose.

People’s Democratic Party

The wild card in this election is the HDP, led by Selahattin Demirtaş. Composed primarily of Kurds mainly in southeast Turkey, the party also attracts some Alevis and Turkish liberals. The HDP hopes to increase its dominance of southeastern Anatolia and pick up enough votes elsewhere in the nation to pass the 10 percent electoral threshold for representation as a party in parliament. The 10 percent voting threshold—the highest such benchmark in Europe and possibly the world—was legislated under the military government that ruled Turkey from 1980 to 1983 as a measure to keep minority parties—some would argue, particularly Kurdish parties—out of parliament in order to bolster stability after the political chaos of the 1970s. By Turkish standards, the HDP is far to the left, certainly well to the left of the other three major parties. Its professed goal is to make Turkish democracy more inclusive, and the party stresses human rights for minorities, an end to restrictions on freedom of expression, and vast improvements in Turkey’s justice system. The HDP has the highest percentage of female candidates running on its party list and pledges in its election manifesto to “enable LGBT individuals to lead an equal, honorable … life.” The HDP emphasizes the importance of government transparency, and its leaders claim they want to end some of the AKP government’s more opaque measures, such as the presidential discretionary fund. If the HDP passes the 10 percent threshold, it could play the role of kingmaker in a coalition government in return for constitutional reform and further devolution of power to local governments. However, the HDP’s ultimate goal is to create a federal system in Turkey, including greater autonomy for local and provincial governments and the popular election of governors. These shifts would allow Kurds greater control over language, taxation, education, and policing.

Key issues

Economic concerns

The first major issue defining the election—and probably the foremost issue in the minds of Turkish voters—is slowing economic growth. The AKP’s political success has been based in large part on the rapid economic growth that Turkey enjoyed for much of the party’s first decade in charge. But Turkish growth slowed to 2.9 percent in 2014, unemployment ticked up to 11.2 percent in first quarter of 2015, and the Turkish lira is near a record low against the U.S. dollar. Turmoil in Iraq and Syria and slow growth in the eurozone have hurt exports, which were down 13.4 percent in March 2015 from the previous year. And 14 percent inflation of food prices has hit voters’ wallets and forced the AKP to consider increasing food imports. The AKP has never before entered a general election with a struggling economy, and anemic growth could spell trouble for its parliamentary majority.

Presidential proposal and changes in the AKP

Perhaps the most hotly debated aspect of the election is President Erdoğan’s proposal to move the country to a strong presidential system, which would require parliament to rewrite the constitution. President Erdoğan argues that the system established by the Turkish Constitution of 1982 is illegitimate because it was established under a military junta. Erdoğan also says that a presidential system would allow for more efficient government and stronger economic growth. Prime Minister Davutoğlu has backed the move after some initial reluctance. However, all of the major opposition parties oppose the proposal for a strong presidency. They fear that President Erdoğan wants to use a presidential system to consolidate his hold on power and is primarily concerned with eliminating legitimate checks on his authority. The AKP would need 330 parliament seats to put proposed constitutional changes to a national referendum and 367 seats to change the constitution unilaterally. According to Turkish pollsters Gezici and A&G, the Turkish public opposes the proposed presidential change, with 76.8 percent and 70 percent of those surveyed, respectively, in favor of keeping the current parliamentary system of government. Another Gezici poll found that 64 percent of AKP voters oppose the proposed move, even though they support the president’s party. Despite the unpopularity of the presidential proposal, opponents of the initiative fear that Erdoğan might be able to carry a national referendum by making it a personal vote of confidence and appealing to his popularity with half the country, much as he did in the August 2014 presidential election, when he won nearly 52 percent of the national vote.

The AKP also faces internal issues on the eve of the election, which could signal public dissent if the party loses ground on June 7. Party rules prevent members of parliament, or MPs, from serving more than three terms, which means that veteran AKP officials such as party co-founder and Deputy Prime Minister Bülent Arınç, former Deputy Prime Minister Beşir Atalay, Economy Minister Ali Babacan, Deputy Party Chairman Hüseyin Çelik, Minister of Energy and Natural Resources Taner Yıldız, and Foreign Minister Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu will all be excluded from formal roles in a new AKP government. In total, 60 sitting AKP MPs cannot run for parliament again.

The shake-up of the party list has contributed to unusually public tensions within the AKP. There are signs that elements within the AKP are concerned about President Erdoğan’s dominance of the party and the unpopularity of his proposed move to a presidential system. Erdoğan’s assertiveness in declaring government policy—despite the dubious constitutionality of such actions by the president in the current parliamentary system—led Deputy Prime Minister Arınç to remark to reporters that “responsibility is with the government and we can take his statements as personal views.” Arınç’s comment provoked the combative AKP mayor of Ankara, Melih Gökçek, an Erdoğan loyalist, to call for Arınç’s resignation. The heated public exchange spun out of control from there and eventually required Prime Minister Davutoğlu to intervene and declare the debate over, warning that he “won’t tolerate any moves that will harm our party before or after the elections.” It is clear that President Erdoğan has an unparalleled ability to dominate the news cycle in Turkey, and his political interventions—which are becoming increasingly provocative on issues such as the Kurdish peace process—clearly make some AKP members uneasy. These tensions might boil over should the party lose big on June 7.

Finally, several narrower political developments will shape the June vote. Turkish expatriates will be allowed to vote for the first time in a general election. Turks living in Europe, notably the 1.4 million Turkish citizens in Germany, have already begun early voting. In a poll by Germany’s Ethno-Forschung, 60.8 percent of Turks living abroad indicate support for the AKP, while 17.2 percent support the HDP. The CHP and MHP received 10.1 percent and 11.9 percent, respectively.

Kurdish peace process

The ongoing Kurdish peace process has also been a very divisive issue in Turkish politics and has shaped the current election in several ways. All the parties except the MHP support the negotiated disarmament of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, or PKK, which Turkey, the United States, and the European Union still regard as a terrorist organization. The MHP insists on unilateral disarmament by the PKK, without corresponding concessions from the government. For three years, the AKP and the PKK have engaged in delicate talks to secure a long-term settlement, including disarmament, the reintegration of PKK militants into society, and the devolution of some central government authorities to local governments, particularly in the majority-Kurdish provinces. The negotiations have been accompanied by an uneasy ceasefire, largely upheld by both sides—a welcome respite for a region long plagued by PKK-Turkish clashes. However, tensions remain high, as illustrated by an April clash in Ağrı, near the Iranian border, that left five PKK militants dead and four Turkish soldiers wounded.

The AKP has walked a delicate line in these negotiations; any deal must achieve PKK disarmament and protect the cohesion of the Turkish state while addressing demands for greater representation from Kurds who have been long repressed by aggressive state policies of assimilation. But the AKP risks alienating a deeply nationalistic Turkish polity and provoking an electoral backlash if it is seen as conceding too much to the PKK or giving special privileges to Kurds generally. The AKP’s strategy has, therefore, been one of incremental reform with the hope of slowly addressing Kurdish concerns while upholding the ceasefire and avoiding concessions large enough to mobilize an aggressive nationalist response.

That strategy has largely worked politically: The AKP and HDP have generally split the Kurdish vote, and the AKP has not lost meaningful ground to the far-right MHP. But the June 7 election will test the ongoing viability of the approach, with two primary political risks for the ruling party. First, the slow pace of reform and the crisis in Kobani—a Syrian border town where the AKP was criticized for failing to aid Kurdish forces fighting the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham, or ISIS—could combine to alienate some conservative Kurds who have previously voted for the AKP and lead them to vote for the HDP in the upcoming election. Second, the peace process and regional developments have emboldened Kurdish leaders to take public positions in favor of Kurdish autonomy, which would have been unthinkable several years ago. This, in turn, may lead to an uptick in support for the far-right MHP.

The AKP and previous governments have been shielded from a meaningful Kurdish political challenge by the 10 percent threshold law, legal bans on Kurdish political parties, and the hostility of the wider Turkish electorate to Kurdish parties—which are often seen as close to, if not controlled by, the PKK, a group that is anathema to most Turks. But this reality has started to change: The HDP has made an effort to reach out to non-Kurds; Turkish society has become more open to Kurds overall, thanks in part to the AKP’s reforms: and liberals have largely abandoned the AKP, with some likely to vote for the HDP. Although the AKP has begun to allow limited Kurdish language instruction in schools and made some efforts to develop the neglected Kurdish heartland in the southeast, a majority of Kurds today support the HDP. This trend accelerated after the AKP’s—particularly President Erdoğan’s—rhetoric in response to the ISIS assault on Kobani in Syria, which many Kurds viewed as anti-Kurdish.

Collectively, these trends mean that the HDP is approaching the 10 percent threshold for representation as a party in parliament, which would propel it to a record number of seats. But if the HDP falls short of 10 percent of the vote nationwide, the 54 seats to 60 seats for which it is competitive would default to the party that receives the second-highest number of votes in that district, undoubtedly the AKP in southeastern Turkey. In the 2011 general election, for example, the HDP’s predecessor party ran independent candidates—rather than as a party—to circumvent the 10 percent threshold and won 36 seats; the AKP was the second-place finisher in every single case. This means that a tiny swing either more or less than 10 percent for the HDP could result in a massive change in parliament, one that could either hand the AKP the majority it needs to initiate constitutional changes or force it into a coalition government. In this way, the fate of constitutional reform and the Kurdish peace process are deeply linked and rely on the outcome of the June 7 vote.

Rise of the nationalists?

A fourth issue that is shaping the election and Turkish politics is a recent rise in nationalist sentiment, which is most visible in growing support for the ultranationalist MHP. This has important ramifications for the election result and for potential coalition politics in the wake of the vote. While opinion is split over whether the HDP can reach the 10 percent threshold, the odds are good that the MHP will increase its share of the vote by between 2 percent and 4 percent. One reason for this is structural: The Turkish population and educational system remain very nationalistic. Dating back to the foundation of the modern republic and the reforms of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk following the destruction of the Ottoman Empire, Turkey’s educational and cultural institutions have been dedicated to reinforcing state control and building national unity in order to resist further erosion of the nation-state—hence the constitution’s rhetorical emphasis on the “will of the nation” and the inviolability of the Turkish state. Until 2013, Turkish students were required to recite a daily oath that read, “I am a Turk, honest and hardworking. My principle is to … love my homeland and my nation more than myself.” Such strong nationalist foundations have often helped the MHP; recently, the party has become a default stance for some Turkish voters who have grown dissatisfied with the AKP and do not see the CHP or HDP as viable alternatives.

Recent diplomatic snubs from foreign powers and the Syrian refugee crisis may have also contributed to the increase in support for Turkey’s nationalists. The international community’s support for Armenians during the centennial of 1915 led to an outpouring of Turkish nationalism; indeed, Turkey’s three largest parties—which can agree on little else—issued a joint declaration condemning the European Parliament’s resolution to recognize the 1915 Armenian genocide. Meanwhile, Turkey hosted more than 2 million Syrian refugees and has spent over $5 billion in humanitarian aid since the beginning of the conflict as of May 2015. In border towns such as Reyhanlı and Kilis, Syrian refugees outnumber Turks. The AKP’s moves to provide social services to the refugees has produced a backlash from some voters, who believe some refugees should be relocated back across the border. The CHP and MHP have sought to channel many Turks’ concerns about access to jobs and health care in light of the resources spent caring for Syrian refugees and the influx of cheap labor.

The MHP has stuck to its traditional confrontational line regarding the Kurds, arguing that there can be no reconciliation with the PKK, that reforms benefiting the Kurdish population are ill advised, and that the peace process will lead to the disintegration of Turkey. But the party’s election manifesto expresses support for increased rights for Alevis: Party leader Bahçeli has promised that his party would recognize and protect Alevi places of worship and include Alevi clerics in Turkey’s Diyanet, or religious affairs bureau, should it enter the government. This marks a serious departure for the MHP, which has traditionally been hostile toward Alevis, and the softer tone may be an effort to lure nationalist, secular Alevis who generally vote for the CHP to vote for the MHP or help prepare for potential cooperation between the MHP and CHP after the election.

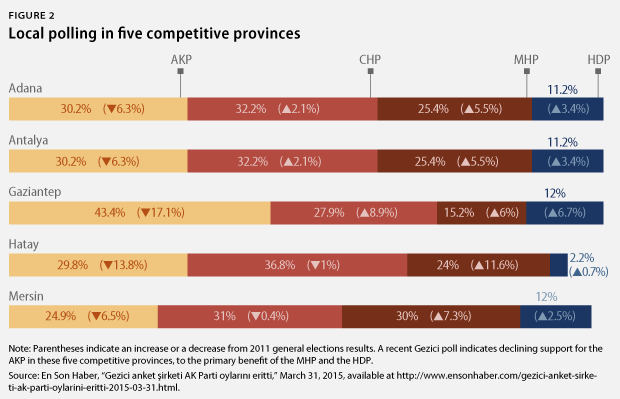

Potential outcomes

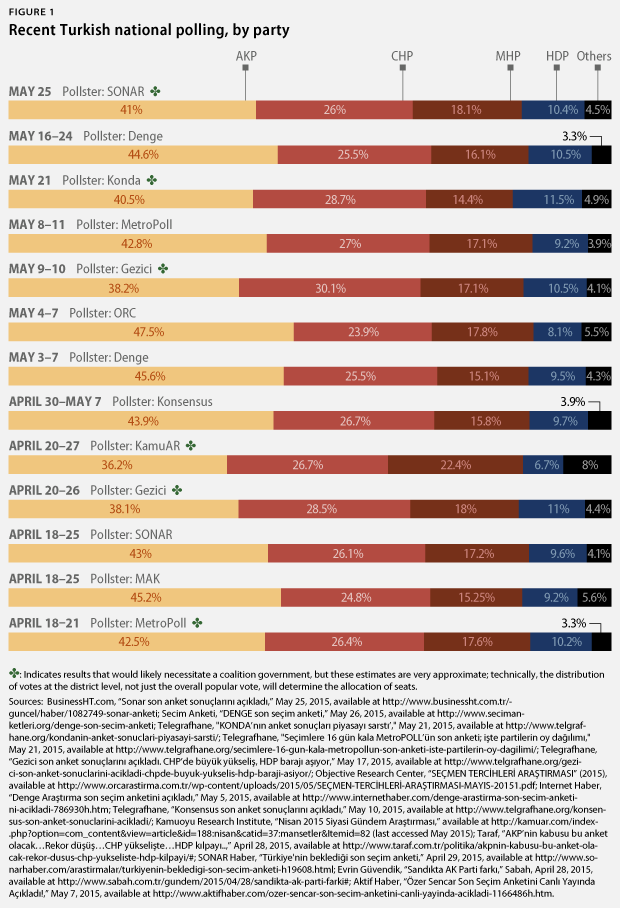

National polling in Figure 1 shows public support for the parties and the potential need for a coalition government, but estimates about the exact allocation of seats are very approximate and depend on the distribution of votes by district, not just the overall popular vote. Still, the national polling indicates a realistic chance that Turkey will require a minority or coalition government in parliament. Locally, polling in five competitive provinces—shown in Figure 2—illustrates the decline in support for the AKP, which primarily benefits the MHP and HDP.

Despite a likely decline in its overall share of the vote, the AKP could gain additional seats in parliament in June if the HDP fails to reach the 10 percent threshold. As the only other competitive party in Turkey’s Kurdish regions, any seats that the HDP wins would default to the AKP if the HDP received less than 10 percent nationwide. Without the HDP in parliament, the AKP would easily be able to form a single-party government, and the fate of proposed constitutional changes would depend on CHP and MHP gains or losses. For example, if the CHP maintains 25 percent to 26 percent of the vote and the MHP increases to 17 percent to 18 percent, then the AKP would fall short of the 330 MPs needed to put constitutional proposals to a referendum, and the proposed move to a presidential system would likely be abandoned. It is unlikely that the CHP and MHP could form a coalition government without the HDP in parliament and supportive of the coalition, as polls suggest that the AKP will not drop below 40 percent of the vote, and in that case, the CHP and MHP’s gains would not be enough to outnumber the AKP.

However, even a small HDP victory would dramatically alter the composition of parliament and might force a coalition. With 10 percent or 11 percent of the vote, the HDP could gain anywhere from 54 to 60 seats in parliament. In that scenario, the margins for AKP single-party control would be slim and are very difficult to predict—perhaps no more than four seats depending upon the performances of the CHP and MHP in certain districts. For example, if the HDP were to get 11 percent of the vote, the CHP 25 percent, and the MHP 17 percent, that could—according to one calculation—give the AKP around 275 seats, one seat shy of a majority. Such a result could force a minority government that would rely on ad hoc support from other parties or a unstable coalition if the AKP finds ways of luring parliamentarians from other parties to make up a narrow majority.

Coalition options appear limited for Turkey’s political parties, according to their public statements, but such commitments may fade in the wake of a fresh national vote. The AKP has stated it will not form a coalition with any party and will form a minority government if necessary. The MHP has ruled out participating in any coalition with the AKP or the HDP. The CHP remains the most open to the formation of a coalition government. Indeed, the CHP fielded a joint presidential candidate with the MHP in the 2014 presidential election and, separately, supported the HDP position on the Ağrı incident. These positions may indicate openness to forming a coalition government with either party. Neither the HDP nor the CHP are likely to form a government with the AKP due to their resistance to the proposed presidential system and the AKP’s religiously tinged ideology; both CHP and HDP are resolutely secular. Still, observers have long discussed the possibility that the HDP would set aside its mistrust of the AKP and form a coalition in which it provides support for AKP-led constitutional reform with the understanding that the new constitution would provide greater authority for local governments, remove problematic anti-terror provisions that are most often used against Kurds, and tone down the aggressive ethnic nationalism of the current constitution. But this appears very unlikely after the anger and protests elicited by the Kobani crisis and the rhetoric from the two parties has grown so heated that reconciliation may be all but impossible.

Nevertheless, no coalition combination should be absolutely ruled out, as the lure of government and its many perks could prove irresistible. Even an unlikely CHP-MHP-HDP coalition—or a slightly less unlikely CHP-MHP minority government, with conditional HDP support from the outside—could conceivably emerge, even if it is only short lived and for a specific purpose, such as lowering the election threshold or opening corruption investigations against the AKP. While a short-lived three-way coalition between CHP-MHP-HDP might make sense to deal a blow to the dominant AKP, it is less likely because of MHP-HDP hostility. Additionally, Turkish MPs earn a pension only if they have served at least two years in parliament, so some members might not want to form a temporary and likely unstable three-way coalition that might jeopardize their pension payments if they lose re-election or get dropped from party lists. Most likely, none of the three main parties would coalesce with the HDP because of its perceived association with the PKK.

So the election will come down to whether the HDP can clear the 10 percent threshold and the size of AKP losses. The most likely outcomes are continued AKP single-party rule or an AKP-MHP coalition government. While both MHP leader Bahçeli and AKP Prime Minister Davutoğlu have ruled out a coalition, it may emerge as the only option to secure a majority in parliament. The AKP and MHP share a similar political base and conservative principles, and the hostility between the HDP and MHP makes almost any other conceivable coalition unworkable.

If the HDP does not make the threshold and the AKP secures an outright majority, President Erdoğan would push parliament to enact his presidential proposal as part of constitutional reform. Depending on the size of the victory, however, other elements within the AKP that oppose the presidential system and are worried about Erdoğan’s dominance may try to differentiate themselves. Undoubtedly, however, an outright AKP majority would bring four more years of more conservative and religious politics. It would also likely mean continued active support for Islamist Syrian rebels and, possibly, renewed work to secure a lasting peace with the PKK. While it may bring stability, an outright AKP win would also likely mean further anti-Western rhetoric and more pressure on political dissent and freedom of expression at home, along with ongoing efforts by the AKP to assert political control over the judiciary.

If the HDP does make the threshold and the AKP is forced into a coalition—most likely with the MHP—the government is likely to take a stronger nationalist line at home but adopt, perhaps, a more restrained foreign policy. The AKP would be pressed by its coalition partners to moderate its support for Islamist political parties in the region. In particular, Turkey’s assertive policy on Syria might prove difficult to sustain in a coalition with the MHP. Both parties would likely be comfortable with continued pressure on journalists and the media. Anti-Western rhetoric, which has become an AKP staple, would continue. The MHP would likely oppose any move to devolve new powers to local governments and would almost certainly scuttle any constitutional reform effort in the direction of enhanced powers for Erdoğan. Perhaps most importantly, an AKP-MHP coalition would be unlikely to make any concessions as part of the Kurdish peace process, which might prompt renewed PKK insurgency or Kurdish political efforts to establish local autonomy outside the formal political structures.

Conclusion

Whatever the outcome, Turkey is headed toward its most exciting and potentially decisive election in more than a decade. With three, or sometimes four, major parties competitive in certain key districts, unreliable polling, and the distorting effect of the 10 percent threshold at play, it is almost impossible to call in advance. What is certain is that the result will be crucial for Turkey and important for the United States. Perhaps most importantly, the conduct of the vote could rejuvenate or doom Turkey’s reputation as a modern democracy.

Michael Werz is a Senior Fellow at the Center for American Progress. Max Hoffman is a Policy Analyst at the Center. Mark Bhaskar is an intern at the Center.