Introduction and summary

“In the nearly seven years since I transitioned, I have been unemployed, surviving off the charity of friends and family, and government assistance when I could get it. I have over 20 years of experience in my field, yet I cannot even land a part-time retail position.”

— Respondent to the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey1

Employment discrimination, along with discrimination in housing and health care, is all too common in the LGBTQ community. It can impede LGBTQ people’s ability to attain and maintain economic security. That’s why it’s crucial that LGBTQ people have access to supports that help them put food on the table, access health care, and put a roof over their heads. Despite high need for public benefits in the LGBTQ community, access to these benefits is far from assured. At the state and federal levels, there are recent and ongoing attacks on programs that ensure basic living standards, including the implementation of harsh work requirements for recipients of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and Medicaid and proposed funding cuts to SNAP in the House farm bill.2 These efforts increase the urgency to examine how cuts to benefits such as nutrition assistance and Medicaid could affect the LGBTQ community.

While research has shown that members of the LGBTQ community report lower incomes and higher rates of poverty, increased food insecurity, higher unemployment, and greater vulnerability to homelessness than the general population,3 additional research is needed to examine LGBTQ people’s receipt of a range of crucial benefits that may help address those issues. The new Center for American Progress survey data explored in this report use a nationally representative sample of both LGBTQ-identified and non-LGBTQ-identified adults to deepen the understanding of the extent to which the LGBTQ community receives certain benefits and determine whether disparities exist on the basis of LGBTQ identity and other demographic factors.

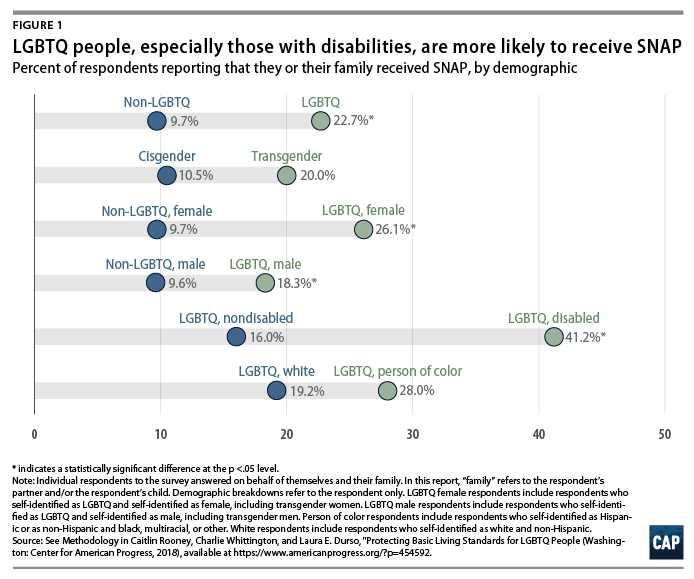

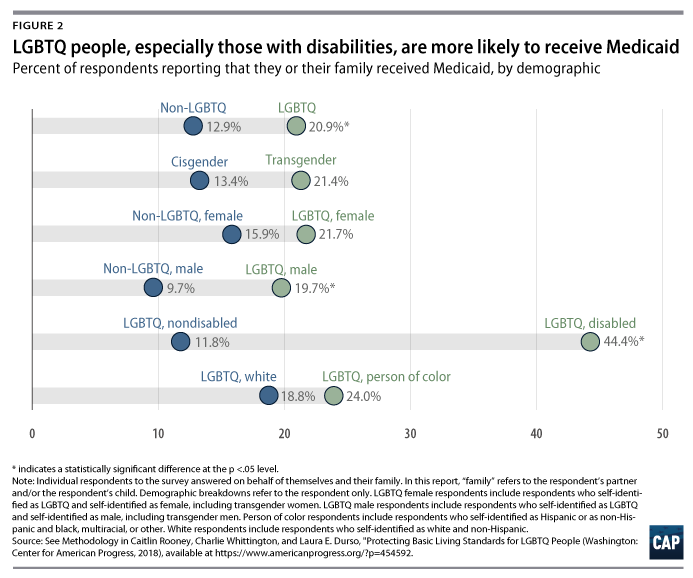

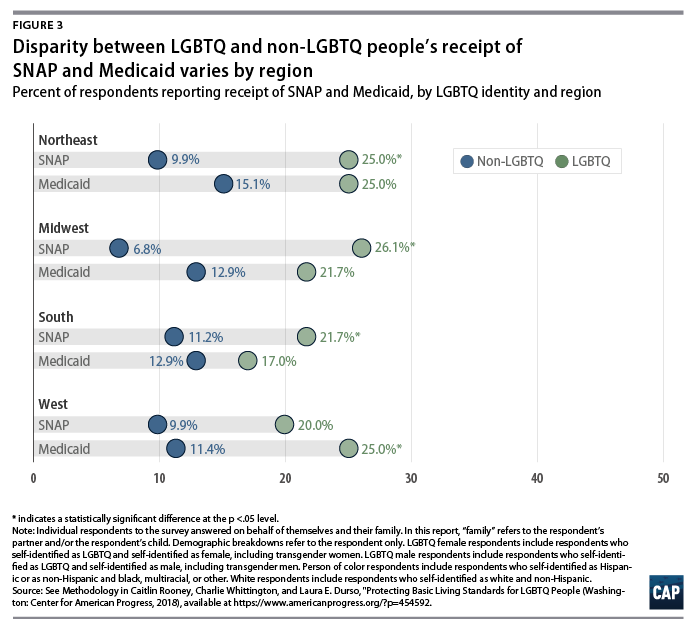

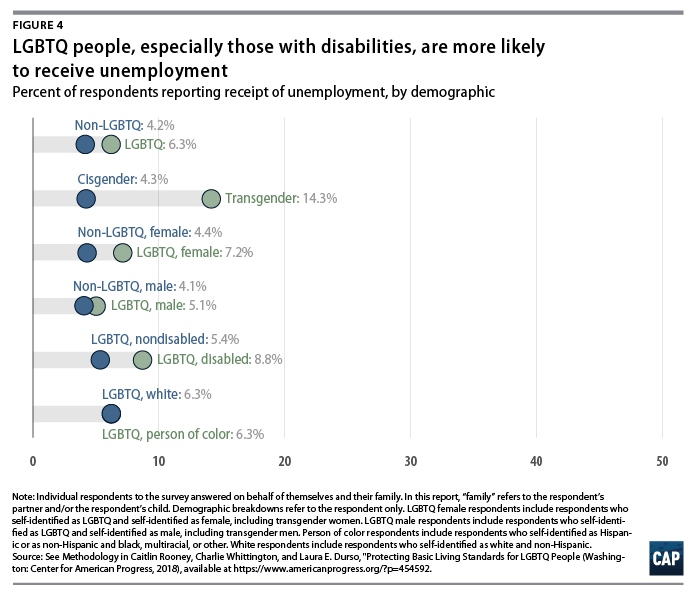

The CAP survey responses—collected in 2017 and summarized in Figures 1 through 5—indicate that LGBTQ people and their families4 are more likely to participate in a range of public programs than non-LGBTQ families. Survey respondents were asked whether they, their partner, or their child received assistance from SNAP, Medicaid,5 unemployment,6 or public housing assistance in the year preceding the survey. In general, a greater proportion of LGBTQ respondents reported that they or their families had participated in these programs compared with non-LGBTQ respondents. The following analysis presents descriptive data about receipt of these benefits by sexual orientation and gender identity, as well as other important demographic characteristics such as gender, race and ethnicity, and disability status. The survey’s findings underscore the importance of opposing benefits cuts, including work requirements, that would likely disproportionately harm the LGBTQ community. Instead of cutting these benefits, state and federal governments should expand these crucial supports and forward other policies proven to help boost wages and improve the economic security of all people, including LGBTQ people.

Examining benefit receipt through government and nongovernment data sets

Official statistics on receipt of benefits such as SNAP, Medicaid, unemployment benefits, and public housing assistance are collected and reported by the federal agency administering the benefit through administrative data sets. These data sets, like the overwhelming majority of government sources, do not yet collect data on sexual orientation or gender identity.7 Even when publicly released administrative data contain other demographic and economic information on recipients, survey data often allow for more in-depth analysis of those demographic factors. Data in the present analysis differ from existing administrative data due to the way the information was collected, and these separate data sets should not be compared directly. Data from the CAP survey are based on self-reporting, the respondent’s knowledge of their and their family’s receipt of a benefit, and the receipt of a benefit at any point in the past year. Administrative data are typically based on agencies’ point-in-time counts of how many individuals or households actually received a benefit in the past month or how many units of benefits or dollars were disbursed. Data in the present analysis likely yield conservative estimates of the receipt of these programs, since research has shown people tend to underreport their participation in various programs, including SNAP and Medicaid, in surveys.8 While the rates of receipt in the CAP survey are likely conservative, the disparity between LGBTQ and non-LGBTQ families’ reported receipt of benefits is important information that deepens the understanding of these issues and points to additional avenues of research and the value of improved data collection. See the Methodological Appendix for more details about the administration of the CAP survey.

Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program

The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, the nation’s leading program to address food insecurity, helps millions of low-income households afford healthy, nutritious food every month.9 There are three main requirements for SNAP eligibility: A household’s gross income must be equal to or less than 130 percent of the federal poverty level; the household’s net income must be equal to or less than the poverty level; and the household must have assets less than a maximum value of $2,250 or $3,500, depending on the household’s composition.10 While SNAP is key in helping individuals and families put food on the table, it does not serve everyone experiencing food insecurity, and it provides only a modest benefit to those it does serve.11 The average benefit is about $1.40 per person per day, and most families receiving SNAP run out of those funds before the end of the month.12

Prior research from The Williams Institute shows that LGBTQ people are more likely than non-LGBTQ people to experience food insecurity or have limited access to adequate food due to a lack of resources, including money. According to the institute’s analysis of a survey conducted in 2014, LGBT people were about 1.5 times more likely to have experienced food insecurity in the past year than non-LGBT people. Data from the National Health Interview Survey suggest that bisexual women in particular face high rates of food insecurity compared with people with other sexual orientations, though the difference was not statistically significant.13

The CAP survey corroborates prior research by The Williams Institute and the National Center for Transgender Equality14 and finds that LGBTQ respondents reported that they or their family received SNAP benefits at more than twice the rate of non-LGBTQ respondents. (see Figure 1) SNAP may serve as a particularly helpful resource to the LGBTQ community because of the program’s broad definition of a household. For eligibility purposes, SNAP defines a household as any person or group of people who buy and prepare food together, and that broader definition likely fosters more inclusion of LGBTQ people, many of whom have chosen family—people with whom they have close bonds that are similar to the bonds traditionally associated with relationships based on blood or legal ties, such as marriage or adoption—that do not fit traditional family structures.15

Medicaid

Medicaid is a health insurance program administered at the state level that provides free or low-cost health insurance to low-income families, older adults, and some people with disabilities, though eligibility and costs vary by state.16 In 2018, the maximum income threshold for populations deemed eligible by states ranges from as little as 18 percent of the federal poverty level in some states to 221 percent of the poverty level in others and is often higher for parents than individual adults.17 In some states, childless adults without disabilities cannot qualify for Medicaid.18 The decision of 34 states to expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act to cover more people in need of affordable health care—including able-bodied low-income individuals without children and people with disabilities who do not otherwise meet Medicaid’s traditional, strict disability standards—has improved access to affordable health care for LGBTQ people.19

The LGBTQ community faces a wide range of health disparities, including a greater risk of substance use disorder and mental health issues than straight people and cisgender people.20 Gay and bisexual men and transgender women face a greater risk of HIV infection than others within and outside the LGBTQ community, and bisexual women have a higher risk of cancer than either lesbians or straight women.21 LGBTQ people are also more likely to be uninsured than non-LGBTQ people, but Medicaid, particularly Medicaid expansion, has played a significant role in closing that gap and providing affordable access to health coverage.22

The experience of a participant in the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey illustrates the importance of ensuring health care access for LGBTQ people:

I had suffered from anxiety and depression as a direct result of gender dysphoria. This caused me to become more and more unable to function in society as time went on. Only when my state expanded Medicaid was I finally able to start dealing with all of these issues.23

According to an analysis of surveys conducted by CAP in 2013 and 2014, the uninsurance rate among low-income LGBTQ people dropped more dramatically in states that expanded Medicaid than in states that did not.24 Consistent with LGBTQ people’s need for health care and the importance of Medicaid in LGBTQ people’s ability to access insurance, CAP’s present analysis found that LGBTQ respondents were 1.6 times more likely than non-LGBTQ respondents to report that they or their family had Medicaid coverage in the year prior to the survey. (see Figure 2)25

Unemployment benefits

Unemployment insurance (UI), a critical support for jobless workers, is designed to replace a share of workers’ wages when they are laid off through no fault of their own and are actively seeking another job, though eligibility varies significantly by state. Each state has different requirements for the length of time a worker needs to have been employed and the amount of wages they need to have accrued in a given time period to qualify for UI.26 Nationally, only about one-quarter of unemployed workers receive UI.27

Employment discrimination can often make it difficult for LGBTQ people to find and maintain jobs.28 Existing research shows that transgender people in particular face high rates of unemployment, with the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey finding that the unemployment rate for transgender respondents was three times higher than that of the general population at the time of the survey.29

Since unemployment benefits only serve a small subset of the U.S. population, the number of respondents to the CAP survey reporting receipt of unemployment benefits was low. Likely as a result, the analysis did not find statistically significant differences in reported receipt based on sexual orientation, gender identity, gender, disability status, or race. (see Figure 4)30 However, the CAP survey’s finding that 6.3 percent of LGBTQ respondents reported that they or their family members received unemployment benefits still adds to the understanding of the supports that LGBTQ people receive.

Housing assistance

Numerous programs at the local, state, and federal levels provide safe, stable, and affordable housing to low-income people and their families. At the federal level, the public housing program and Project-Based Rental Assistance provide low-cost rental units to low-income households, older adults, and people with disabilities by subsidizing housing units, while federal Housing Choice Vouchers—commonly referred to as Section 8—provide benefits directly to low-income households to rent housing in the private market.31 However, there is an insufficient number of affordable rental units, and only a small fraction of people who are eligible for federal rental assistance are able to obtain it.32 At the state and local levels, low-income renters must navigate a web of rental assistance programs that vary widely with regard to eligibility, application process, housing quality, funding source and longevity, and other criteria.33

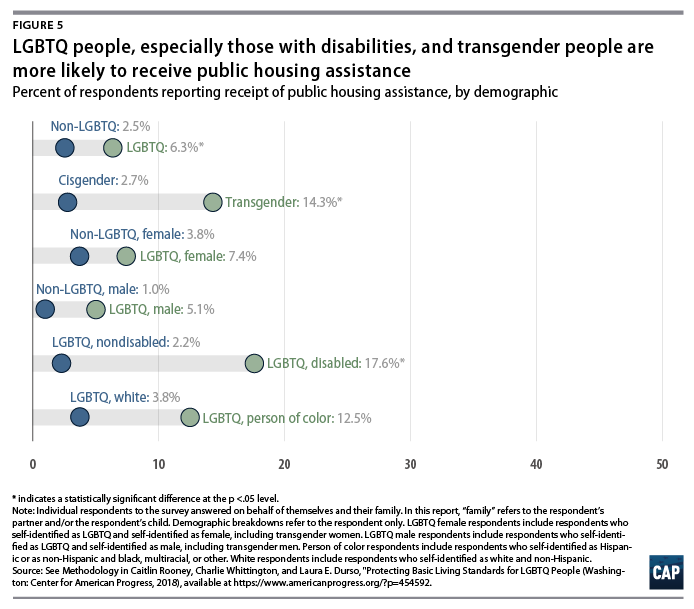

Research suggests that LGBTQ people disproportionately experience homelessness and housing insecurity and that they face discrimination in homeless shelters as well as rental markets, but little is known about LGBTQ people’s participation in housing programs.34

The CAP survey found that LGBTQ respondents and their families relied on public housing assistance at 2.5 times the rate of non-LGBTQ respondents. (see Figure 5)35 While these data illuminate that a disparity exists in receipt of public housing benefits, the survey did not inquire about the specific programs from which survey participants received assistance, and more research is needed to learn the types of housing programs on which LGBTQ people rely.

Policy recommendations

While much research has shed light on the high rate of economic insecurity that LGBTQ people face, the CAP survey presents additional information which shows that LGBTQ people are accessing programs that provide basic living standards at higher rates. This suggests that cuts to benefits such as nutrition assistance, Medicaid, unemployment benefits, and public housing assistance would likely disproportionately harm the LGBTQ community.

One of the main ways in which Congress, state governments, and the Trump administration are attempting to cut benefits is by introducing or expanding so-called work requirements, which set strict time limits for a person to receive benefits if they are unable to find work—no matter how hard they are searching—or engaging in a qualifying training program for a certain number of hours per week.36 Research shows that these types of onerous requirements do not help people become stably employed.37 Instead, they hurt struggling workers and exacerbate the barriers they face to gainful employment, since it’s a lot harder to find and keep a job while going hungry or dealing with health issuesThese requirements may be particularly harmful to LGBTQ people.38 Under strict work requirements, LGBTQ people who are fired, laid off, or struggling to find a job due to discrimination may lose the crucial supports they need, such as nutrition assistance or health insurance. Instead of helping reduce barriers to work for LGBTQ people, work requirements would in effect punish them for facing discrimination by taking away their access to nutrition assistance, affordable health insurance, or housing assistance. This is particularly worrisome in the many states that lack a clear law prohibiting anti-LGBTQ employment discrimination, which includes 8 out of the 11 states with approved or pending work requirements for Medicaid.39

Instead of cutting these benefits, Congress and state legislators should be expanding access and providing more funding to ensure that they can better support the people who need them. Even as LGBTQ people and their families reported receiving benefits at a higher rate, there are likely more LGBTQ people who are in need of assistance than are currently receiving it. The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, Medicaid, unemployment benefits, and public programs that provide housing assistance reach only a fraction of the population that needs them and only provide modest benefits.

In addition, policies proven to help boost the wages of struggling workers, such as raising the minimum wage and fair scheduling practices, should supplement benefits to ensure that families are better able to put food on the table and keep a roof over their heads.40 Public programs that provide basic living standards should not take the place of employers providing their workers with a living wage and good working conditions. And passing the Equality Act—the federal bill that protects LGBTQ people from discrimination in the workplace, housing, credit, and public accommodations—would help eliminate some of the unique barriers that LGBTQ people face in attaining economic security.41

Lastly, federal agencies collecting data on receipt of benefits should determine whether it’s feasible to collect data on sexual orientation and gender identity. Having more data on the LGBTQ community’s receipt of these benefits would help policymakers make more informed decisions about these programs that take into account the unique needs of the populations they serve. The federal LGBT Data Inclusion Act would ensure that all federal agencies collect sexual orientation and gender identity data as appropriate in data sets and surveys, which would provide information not only on LGBTQ people’s receipt of benefits but also on their economic circumstances and unique needs.42 This would help policymakers combat the disparities that LGBTQ people face and develop solutions to boost their economic well-being.

Conclusion

LGBTQ people face unique barriers to economic security, and as a result, they face higher rates of poverty, food insecurity, uninsurance, unemployment, and housing insecurity, among other disparities. Unfortunately, since government agencies often do not collect data on sexual orientation and gender identity, limited data exist on the supports that LGBTQ people receive to address some of these disparities. Data from a nationally representative survey conducted by the Center for American Progress in 2017 indicate that LGBTQ people and their families generally receive benefits from programs that provide basic living standards, including the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program and Medicaid, at higher rates than non-LGBTQ people and their families. These findings suggest that ongoing state and federal attacks on these benefits, including the implementation of harsh so-called work requirements, would likely disproportionately harm the LGBTQ community. This underscores the importance of opposing these benefit cuts, fighting to expand these benefits, and implementing other policies that help all people, including those who are LGBTQ, attain economic security.

Methodological appendix

To conduct this study, the Center for American Progress commissioned and designed a survey, fielded by GfK SE, which surveyed 1,864 adults, including 857 adults who identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual, and/or transgender, queer, or asexual—including 80 transgender respondents—and 1,007 who identified as heterosexual and cisgender/nontransgender. The data are nationally representative and weighted according to U.S. population characteristics. After weighting, the sample size of all LGBTQ respondents was 135, and the sample size of transgender respondents was 16. Respondents came from all income ranges and were diverse across factors such as race, ethnicity, education, geography, disability status, and age. The survey was fielded online in English in January 2017. All comparisons presented with an asterisk in the figures are statistically significant at the p < .05 level. Comparisons that were not found to be statistically significant do not have an asterisk.

The survey predominantly asked respondents questions about their experiences with health insurance and health care, but it also asked a few questions about receipt of various government benefits. Survey respondents were asked whether they, their partner, or their child received help from “SNAP or Food Stamps,” “Medicaid,” “Unemployment,” or “Public housing assistance” in the year preceding the survey.

A few unique characteristics of these data differentiate them from existing administrative data that are typically used to report on receipt of these benefits. These characteristics are discussed in the sections below.

Family data

The CAP survey asked individuals to answer on behalf of themselves, their partner, and/or their child, whereas data on various programs are reported by individual—which may lead to a higher count than the CAP survey—or by household, which could lead to a lower count than the CAP survey.43 The well-known statistic that approximately 1 in 5 people participates in Medicaid is based on individual-level data and cannot be directly compared to the CAP survey data on a respondent’s family’s participation in Medicaid.44 The CAP survey also relies on the respondent’s knowledge of their partner and/or child’s receipt of given benefits, and some research suggests that survey respondents may not have a full understanding of the exact supports their family members, including their partners, receive.45

Self-reporting and underreporting

Research shows that when people are asked to self-report receipt of various benefits including SNAP and Medicaid, they tend to underreport compared with administrative data on actual receipt rates.46 Since the CAP survey relies on self-reporting, it likely provides a conservative estimate of receipt among LGBTQ and non-LGBTQ people. The disparity that the CAP survey finds between LGBTQ and non-LGBTQ people’s receipt of benefits would likely still hold.

Point-in-time vs. in-the-past-year estimates

The CAP survey asked individuals to report on their family’s receipt of a given benefit if they received it at any point in the past year. Agencies typically report receipt of benefits through point-in-time estimates, which capture a smaller group of people. Asking about receipt of benefits across a longer time span may better illustrate the reach of basic living supports than point-in-time estimates, since the group of people who may at some point turn to these benefits is not a fixed group but an everchanging one.47

Wording of questions

The wording of these questions did not align perfectly with discrete government programs, which differentiates them from administrative data about receipt of a given program. Research shows that survey respondents are not always able to identify the exact terms for the benefits they receive.48 However, it is likely that LGBTQ and non-LGBTQ respondents understood all of the questions in similar ways. Some respondents may have interpreted the question about unemployment to encompass Trade Adjustment Assistance (TAA) programs, which provide benefits to workers who become unemployed due to increased imports, rather than simply referring to unemployment insurance.49 Respondents may have interpreted the question about public housing assistance to mean a number of different housing programs. While administrative data sets often combine receipt of Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), the CAP survey asked those questions separately. The base rate for responses to the question on CHIP receipt was too low to report, with only 5 LGBTQ respondents and 49 respondents in total reporting receipt of CHIP, so the present analysis reports only on participation in Medicaid.

Definitions

The definition of “disability” in this survey is based on self-reporting, which is more inclusive and gives a better indication of the prevalence of disability than following the strict standards the government applies when determining eligibility for Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI). Since the government uses the SSDI definition of disability when determining eligibility for SNAP, Medicaid, unemployment benefits, and some housing programs, having a disability under SSDI’s definition is likely a stronger predictor of receipt of these benefits than having a disability under this survey’s definition. Therefore, the percentage of LGBTQ people with self-reported disabilities who reported receipt of various benefits in the CAP survey is likely much lower than the percentage would be among LGBTQ people with disabilities under the SSDI definition.

Additional information about study methods and materials are available from the authors.

About the authors

Caitlin Rooney is a research assistant for the LGBT Research and Communications Project at the Center for American Progress, where she researches and writes about the impact of discrimination in health care, housing, and public accommodations, among other issues. Rooney joined the Center after receiving a bachelor’s degree in legal and political rhetoric with a minor in politics from Whitman College in Walla Walla, Washington. She wrote her senior honors thesis on international advocacy for LGBTQ rights and presented it at the Western States Communication Association Undergraduate Scholars Research Conference. While in college, Rooney participated in the Prison Research Group and the Prison Debate Project, and she helped legalize same-sex marriage in Washington state through her work with Washington United for Marriage. She also interned at the American Civil Liberties Union of Pennsylvania and for Pennsylvania state Rep. Brian Sims (D), the first openly gay member of the Pennsylvania legislature. Prior to joining the Center, Rooney volunteered for the Pennsylvania Prison Society as a lobbyist assistant.

Charlie Whittington is a former intern for the LGBT Research and Communications Project at the Center. She has served in various research capacities at the Edgar Dyer Institute for Leadership and Public Policy, the Congressional Management Foundation, the Georgetown Public Policy Review, and the Democracy Fund. Whittington graduated magna cum laude with a bachelor’s degree in political science from Coastal Carolina University, earning two research awards for her work on gender and leadership. She is currently a graduate student at Georgetown University, where she established and directs an LGBTQ initiative at the McCourt School of Public Policy and studies statistical methodology, American government, and LGBTQ policy.

Laura E. Durso is vice president of the LGBT Research and Communications Project at the Center. Using public health and intersectional frameworks, she focuses on the health and well-being of LGBTQ communities, data collection on sexual orientation and gender identity, and improving the social and economic status of LGBTQ people through public policy. Prior to joining the Center, Durso was a public policy fellow at The Williams Institute at UCLA School of Law, where she conducted research on LGBTQ homeless and at-risk youth, poor and low-income LGBTQ people, and the business impact of LGBTQ-supportive policies. She holds a bachelor’s degree in psychology from Harvard University and master’s and doctoral degrees in clinical psychology from the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Shabab Ahmed Mirza, Katherine Gallagher Robbins, Rachel West, Heidi Schultheis, Sharita Gruberg, and Rebecca Cokley for their assistance with this report.