Introduction and summary

In one of her first acts as secretary of education, Betsy DeVos revoked Obama-era guidance that protected transgender students.1 The 2016 guidance had informed schools that the U.S. Department of Education and the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) interpreted Title IX of the Higher Education Act as protecting all students on the basis of their gender identity, including by guaranteeing access to sex-segregated activities and facilities in accordance with their gender identity.2

The February 2017 joint revocation of this guidance was the first in a series of moves by the Trump administration against LGBTQ youth. Among other things, this list includes trying to remove questions about the sexual orientation of 16- and 17-year-olds from the National Crime Victimization Survey; delaying and then trying to cancel new sexual orientation data collection in the Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System (AFCARS); and targeting protections for survivors of sexual assault in schools, a crisis that disproportionately affects LGBTQ youth.3

In 2018, DeVos officially confirmed that the Department of Education was no longer investigating complaints from transgender students regarding access to bathrooms and locker rooms, as well as a range of other complaints of anti-transgender discrimination.4 This is particularly concerning given data from GLSEN’s 2017 National School Climate Survey showing that more than 40 percent of transgender and gender-nonconforming students report being required to use the bathroom facilities corresponding to their legal sex, and about 40 percent of LGBTQ students avoid gender-segregated spaces in school altogether due to safety concerns.5

All youth deserve a learning environment that is free from harassment and discrimination. LGBTQ students are at particularly high risk for harassment, which underscores the need to ensure that they have equal access to education. GLSEN’s survey found that about 70 percent of LGBTQ students experienced verbal harassment at school based on their sexual orientation, and more than half reported harassment based on gender expression or gender identity.6 Moreover, nearly 30 percent of LGBTQ students were physically harassed for their sexual orientation while almost a quarter were physically harassed for their gender expression or gender identity.7 More than 57 percent of LGBTQ students reported being sexually harassed.8 This mistreatment has significant negative effects, such as causing the affected students to miss school, which leads to lower GPAs and a decreased desire to pursue postsecondary education.9 Worse still, according to the 2017 Youth Risk Behavior Survey, lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth are roughly four times more likely to consider or attempt suicide than their straight peers.10 Similarly, transgender students are approximately four to six times more likely to attempt suicide than their cisgender peers.11

LGBTQ students do have legal protections under Title IX, even if the Department of Education is failing to enforce them. More and more courts have accepted the logical conclusion that discrimination and harassment based on sexual orientation or gender identity are inherently forms of sex discrimination.12 In 2016 and 2017, the U.S. appellate courts for the 6th and 7th circuits, respectively, held that barring a student from using sex-segregated facilities in accordance with their gender identity was a violation of Title IX, joining dozens of federal district courts as well as a number of circuit courts who had previously held that anti-transgender discrimination was a form of sex discrimination.13

In light of DeVos’ revocation of the guidance on transgender students and her decision to end investigations of many of the complaints, the Center for American Progress is investigating how complaints related to sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) have been handled by the Office for Civil Rights (OCR) at the Department of Education. CAP obtained complaint records from the OCR through Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests. After analyzing more than eight years of SOGI-related Title IX complaints, CAP found that:

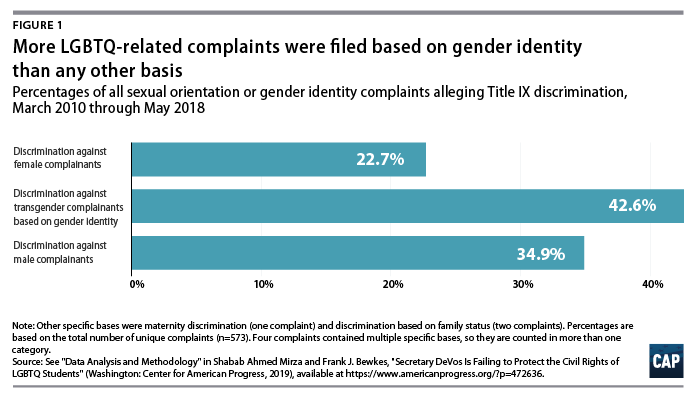

- Transgender students were overrepresented; 42.6 percent of all SOGI-related complaints were filed based on gender identity, even though transgender students make up between 6 and 21 percent of the LGBTQ student population.

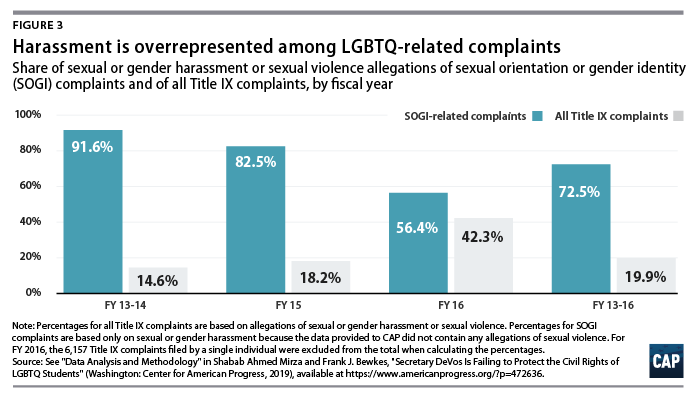

- Harassment was the most frequently occurring allegation in the dataset, with 75.9 percent of all complaints alleging sexual or gender harassment. Comparing the data with other publicly available Department of Education information from fiscal years 2013 through 2016, allegations of harassment appeared more frequently in complaints based on LGBTQ identity than in the general population—72.5 percent versus 19.9 percent.

- One in 6 complaints—14.8 percent—resulted in an action involving a correction in the school’s policies or practices to benefit the student.

The data also showed marked differences in how complaints were resolved since the start of the Trump administration:

- Complaints were more than nine times less likely to result in corrective action than they were under the Obama administration. Only 2.4 percent of LGBTQ-related complaints resulted in an agreement with the school or some other action to correct for the alleged discrimination against the student—compared with 22.4 percent under the previous administration.

- Fewer complaints proceeded to a formal investigation being opened by the OCR. Some complaints may not merit corrective action per the OCR’s case processing standards, but any such decision should be based on fact. The lower rate of investigations raises concerns about whether allegations of discrimination are receiving adequate time and attention prior to the decision not to take corrective action.

The Department of Education has a responsibility to protect the rights of LGBTQ students, and this report confirms that it is failing to do so. To ensure that the department meets the needs of all students, CAP recommends that it:

- Reissue guidance making clear that Title IX protects students from harassment and discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity

- Issue updated technical assistance and training materials

- Increase the budget request for and the number of full-time equivalent (FTE) employees at the OCR

In addition, lawmakers must pass legislation at the state and federal levels to further protect the rights of LGBTQ students. CAP recommends that:

- Congress pass the Equality Act

- Congress pass the Safe Schools Improvement Act

- State legislatures pass state-level student nondiscrimination and anti-bullying laws that enumerate SOGI-related discrimination

These are necessary steps to ensure that all students, including those who are LGBTQ, have their rights properly recognized and enforced, enabling them to thrive both inside and outside of the classroom.

Results

The present study sought to understand more about the nature of civil rights complaints filed by LGBTQ students, how those complaints were handled by the OCR, and whether there were any changes associated with public announcements from the Department of Education regarding Title IX protections for LGBTQ students.

Gender identity discrimination was the most prevalent basis for complaints

More SOGI-related complaints were filed based on gender identity than any other basis. (see Figure 1) This is in line with prior research that found that transgender students reported higher rates of anti-LGBTQ discrimination than their cisgender LGBQ peers.14

Transgender individuals are a minority within the LGBTQ community. In a national survey of LGBTQ adults, only 6 percent of respondents identified as transgender.15 While similar nationally representative data on minors are unavailable, one state-specific survey found a higher estimate, with 21 percent of LGBTQ high school students reporting that they were transgender, genderqueer, genderfluid, or unsure about their gender identity.16 Based on these estimates, transgender students were clearly overrepresented among those who filed SOGI-related complaints, with 42.6 percent of such complaints being filed based on gender identity.

Transgender individuals are a minority within the LGBTQ community. In a national survey of LGBTQ adults, only 6 percent of respondents identified as transgender.15 While similar nationally representative data on minors are unavailable, one state-specific survey found a higher estimate, with 21 percent of LGBTQ high school students reporting that they were transgender, genderqueer, genderfluid, or unsure about their gender identity.16 Based on these estimates, transgender students were clearly overrepresented among those who filed SOGI-related complaints, with 42.6 percent of such complaints being filed based on gender identity.

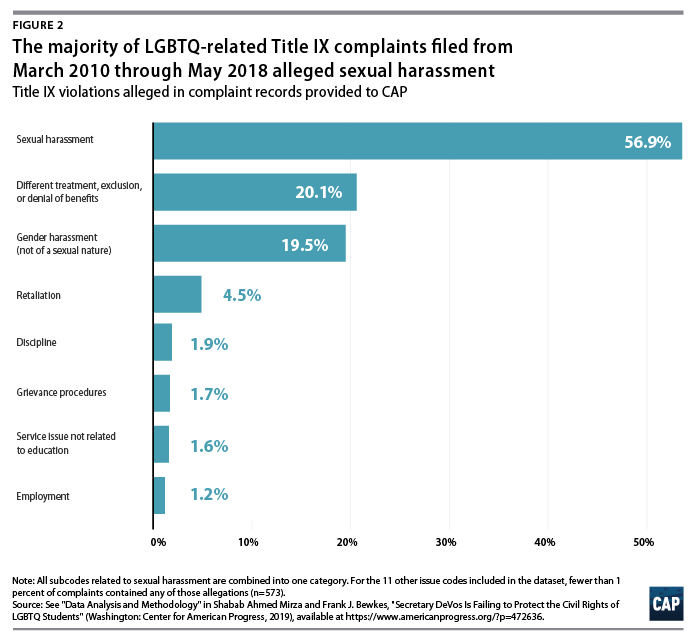

Most complaints alleged harassment

A single complaint can contain multiple allegations of Title IX discrimination. The most frequently appearing issue codes are listed below in Figure 2.

More than three-quarters—75.9 percent—of the complaints in the data provided to CAP contained at least one allegation of sexual or gender harassment.

Harassment was overrepresented among SOGI-related complaints

To contextualize the information provided to CAP, the rates of reported harassment among SOGI-related complaints were compared with the rates of reported harassment for all complaints processed by the OCR. (see Figure 3)

From FY 2013 through FY 2016, the share of complaints related to sexual or gender harassment was higher for SOGI-related complaints than for the general population—72.5 percent versus 19.9 percent. In other words, allegations of harassment were overrepresented among SOGI-related complaints.

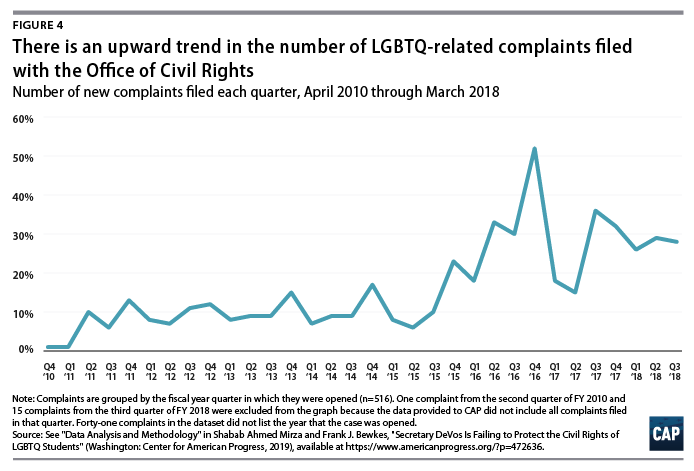

Complaints related to sexual orientation or gender identity have increased over time

There has been an upward trend in the number of new complaints filed each month. (see Figure 5) More complaints were filed in May 2016 than in any other month, which may be due to the announcement of the departments of Education and Justice’s joint guidance to schools regarding transgender students.

There are several possible explanations for the upward trend in the number of complaints filed with the OCR. There may be greater awareness of federal civil rights protections for LGBTQ students, especially after widespread media coverage of state-level bathroom ban legislation in 2016.17 Accordingly, students, their families, and their advocates may be more comfortable reporting incidents of SOGI-related discrimination. And the May 2016 guidance from the Obama administration may have assured them that their civil rights would be protected under federal statute. As advocates have argued elsewhere, reported rates of discrimination are likely an undercount of actual incidents, so an increase in the reported rate may simply signal that complainants have greater confidence that they will be heard.18 It is also possible that actual incidents of discrimination have increased due to a worsening school climate. After years of improvement, from 2015 to 2017, the National School Climate Survey found fewer positive changes in school climate for LGBTQ students, and many schools may have become more hostile toward transgender and gender-nonconforming youth.19

How the OCR processes a complaint

When the OCR receives information about alleged civil rights violations, it takes a standard approach as outlined in its case processing manual.20 The agency first determines whether the information it has received is subject to further processing. In some instances, such as anonymous correspondence or courtesy copies of documents submitted to another agency, the OCR will not process the information any further. If multiple individuals raise identical allegations against a single school at or around the same time, they are treated as a single complaint, whereas identical allegations against different schools are considered separately.

Once a file is established, the OCR will evaluate the complaints based on the information provided. For example, if it is necessary to disclose the identity of the complainant in order to proceed with the case, the OCR will attempt to obtain written consent from the complainant to do so; if the complainant does not provide consent, the complaint is dismissed. Other grounds for dismissal include the OCR determining that it does not have subject matter jurisdiction over the alleged discrimination or jurisdiction over the entity alleged to have discriminated. The case processing manual contains guidelines directing OCR officers to contact the complainant to request further information and to provide appropriate assistance for “persons with disabilities, individuals of limited English proficiency, or persons whose communication skills are otherwise limited.”21 If the OCR is unable to obtain the information necessary to determine whether discrimination or retaliation occurred, the complaint is dismissed and a letter is issued to the complainant explaining the reason for the decision.

If the OCR opens an investigation, it will inform both the complainant and the recipient in writing and provide details about the complaint resolution process. At this stage, the OCR may administratively close the complaint if the alleged discrimination is being addressed elsewhere, if there is a different federal agency better suited to handling the allegation, or if the complainant withdraws an allegation. For example, if an allegation is currently in litigation or is being investigated by a different federal, state, or local civil rights agency, the OCR will not process it any further and will code it as an “administrative closure.” Another example of an administrative closure would be if the OCR refers a complaint of employment discrimination to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC).

Where appropriate, the OCR informs both parties of the option to resolve complaints through an early complaint resolution. This process involves the OCR serving as an impartial, confidential facilitator between the complainant and the recipient and helping them understand the pertinent legal standards and possible remedies. The OCR does not approve or monitor agreements reached between the parties. If the early complaint resolution process is unsuccessful, the OCR will proceed with a regular investigation.

The recipient may voluntarily enter into a resolution agreement prior to the completion of an investigation. Since the investigation is incomplete, the OCR does not determine whether the recipient complied with relevant civil rights regulations. The OCR may also close a complaint file if it receives information that the allegations were resolved with benefit or change to the alleged injured party and that there is no need for an agreement or further monitoring. Both outcomes are coded as “closure with change.”

Once an investigation is completed, the OCR may determine that the preponderance of evidence suggests that the recipient failed to comply with applicable regulations. In such situations, the OCR will negotiate a resolution agreement with the recipient. Resolution agreements are designed to bring recipients into compliance with regulation and are monitored by the OCR until the terms of the agreement are fulfilled. This outcome is another instance of a closure with change. On the other hand, if the preponderance of evidence does not suggest that the recipient failed to comply with applicable regulations, the OCR will close the complaint file and inform both parties. This outcome is coded as “no violation or insufficient evidence.” Complainants may appeal findings of insufficient evidence of a noncompliance determination.

If the negotiation with the recipient is unsuccessful, the OCR will initiate enforcement action, either by initiating administrative proceedings to suspend or terminate federal funding or by referring the case to the DOJ for judicial proceedings. The OCR will also take enforcement action if the recipient denies access to information or fails to comply with an agreement.

Few complaints resulted in corrective action

The OCR handles complaints of Title IX violations following a standard procedure. (See text box on “How the OCR processes a complaint”) All complaints coded with resolution types “early complaint resolution” and “closure with change” indicate that the school took some action to correct the alleged discrimination—in the form an early complaint resolution between the complainant and recipient, a resolution agreement monitored by the OCR, or some other change in the recipient’s policies or practices that benefited the complainant.

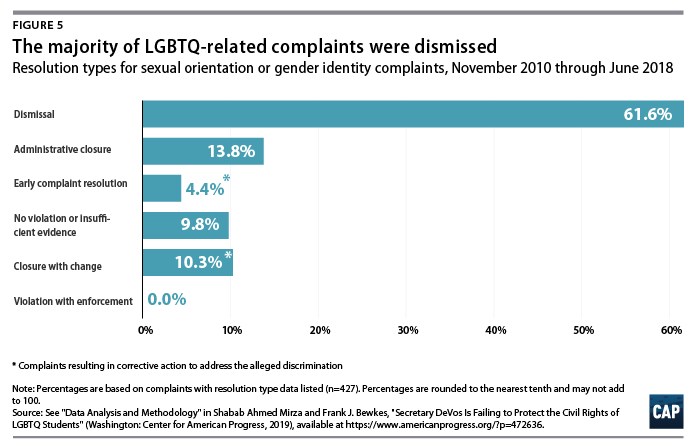

The data provided to CAP in response to the FOIA requests did not contain identical categories of information about the resolution of a complaint. (See Appendix for further data analysis and methodology) Of the complaints with resolution type data available, fewer than 1 in 6—14.8 percent—resulted in any kind of corrective action. (see Figure 6)

The OCR did not find any evidence of wrongdoing for a tenth—9.8 percent—of allegations, meaning that it determined that the preponderance of evidence did not support a conclusion that the recipient failed to comply with applicable regulations.

While resolution types refer to the outcome of an entire complaint, resolution codes indicate how the OCR processed specific allegations of discrimination within a complaint. (See Appendix for further data analysis and methodology)

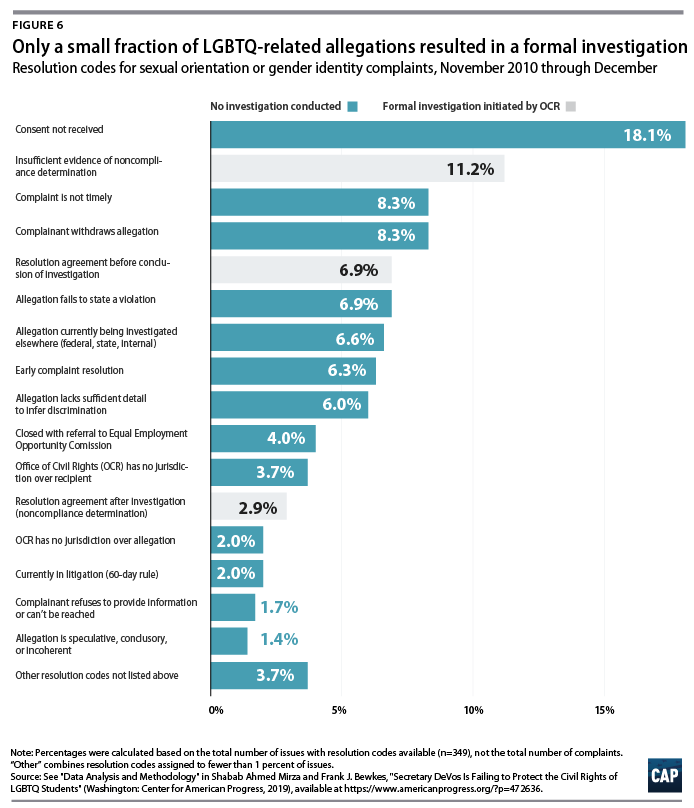

The level of detail provided by resolution codes offers insights into the variety of reasons for which individual allegations are dismissed, which can help to explain the high—61.6 percent—rate of dismissed complaints. (see Figure 6) Of allegations for which resolution code data were available, about 1 in 5—18.1 percent—were dismissed because the OCR did not receive consent from the complainant to disclose their identity. (see text box on “How the OCR processes a complaint”) Other common reasons for dismissal include the complainant withdrawing the allegation, which accounted for 8.3 percent of dismissals, and the complaint not being timely—also 8.3 percent. While an allegation may be dismissed if the complaint is filed more than 180 days after the last discriminatory act, the case processing manual outlines several instances in which the OCR may waive this requirement. For example, if the complainant filed a grievance with their school within the 180-day period, a waiver would be granted assuming the OCR complaint was filed within 60 days of the conclusion of the internal grievance process.

Most OCR investigations that were completed found no evidence of a violation

Only a small fraction of allegations proceeded to an investigation, and even then, there was not always evidence of a violation. Among the subset of complaint records with resolution code data available, 1 in 5 allegations—20.9 percent—were investigated by the OCR, about half of which—11.2 percent of all allegations—were resolved after the OCR found no evidence of noncompliance. (See Figure 6) The OCR completed an investigation and found that the recipient failed to comply with Title IX for only 2.9 percent of allegations.

It is important to note that the OCR administrative process is not itself punitive. It allows educational institutions to voluntarily resolve complaints even before an investigation is completed. Recipients were more likely to proactively address allegations through an early complaint resolution (6.3 percent of allegations) or to voluntarily enter into a resolution agreement (6.9 percent) prior to the conclusion of an investigation than they were to make changes after a completed investigation found evidence of noncompliance (2.9 percent).

Very few complaints were filed against religiously affiliated educational institutions

LGBTQ students at any school can face harassment and discrimination over their sexual orientation or gender identity. However, religiously affiliated institutions can request to be exempt from complying with specific sections of Title IX that they feel conflict with tenets of their religion. Negative experiences reported by LGBTQ students at religiously affiliated institutions that have requested Title IX exemptions include being scared that they will be expelled if they disclose their LGBTQ identity; being removed from student leadership positions; and choosing to leave a promising academic program because of continued bullying, without any response from the administration.22

The data provided to CAP included a small number of religiously affiliated recipients—too few to allow for any meaningful comparisons with recipients that had no religious affiliation.23 Since religiously affiliated schools may apply for Title IX exemptions, students may choose not to file a complaint with the OCR. The Human Rights Campaign found that the majority of schools that requested waivers from FY 2012 through FY 2015 sought exemptions from provisions related to “rules of behavior,” the section of Title IX regulation related to harassment.24 Based on the latest publicly available data from the Department of Education, only 6 of the 111 schools that requested Title IX waivers as of December 31, 2016, appeared in the dataset.

Schools are not currently required to notify students when they are approved for a waiver.25 However, students might not always report discrimination if they know that their school is not welcoming of LGBTQ individuals. The 2017 National School Climate Survey found that more than half of LGBTQ students never reported harassment and that the leading cause for underreporting was that students doubted that school staff would do anything about it.26 The same survey found that students were less likely to report harassment at schools without LGBTQ-inclusive policies.27 These findings suggest that LGBTQ students at educational institutions that request Title IX waivers are less likely to file a complaint with the OCR.

While the number of complaints in the dataset filed against religiously affiliated institutions is low, reports of LGBTQ students being mistreated at institutions that have requested Title IX exemptions signals that misuse of exemptions continues to be a concern.

The OCR has drastically scaled back corrective actions since the election of President Trump

The data were examined to identify any differences in civil rights enforcement in line with Secretary DeVos’ public announcements of policy change. Using case resolution dates, the complaints were compared based on the presidential administration in which they were resolved.

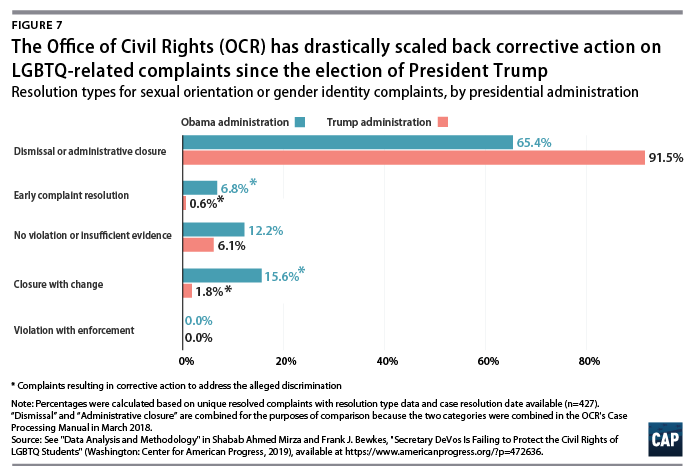

The share of complaints resulting in a dismissal or administrative closure under the Trump administration was much higher than it was under the Obama administration—91.5 percent versus 65.4 percent. Similarly, the percentage of complaints resulting in any kind of corrective action by the recipient—“early complaint resolution” or “closure with change”—was lower under the Trump administration than it was under the Obama administration: 2.4 percent versus 22.4 percent. In other words, SOGI-related complaints were more than nine times less likely to result in corrective action under the Trump administration than they were under the Obama administration.

The share of complaints resulting in a dismissal or administrative closure under the Trump administration was much higher than it was under the Obama administration—91.5 percent versus 65.4 percent. Similarly, the percentage of complaints resulting in any kind of corrective action by the recipient—“early complaint resolution” or “closure with change”—was lower under the Trump administration than it was under the Obama administration: 2.4 percent versus 22.4 percent. In other words, SOGI-related complaints were more than nine times less likely to result in corrective action under the Trump administration than they were under the Obama administration.

SOGI-related complaints were more than nine times less likely to result in corrective action under the Trump administration than they were under the Obama administration.

Actions taken by the Obama administration to protect transgender students were criticized as overreaching and mandating policies that schools were not ready for.28 However, the data show that 12.2 percent of complaints under the Obama administration resulted in a finding of “no violation” or “insufficient evidence”—double the rate under the Trump administration. Under the past administration, recipients were more likely to be found in compliance with Title IX after investigations into SOGI-related complaints. This finding suggests that schools and colleges were prepared to support their transgender students and that the joint guidance issued in 2016 was not unduly burdensome on recipients of federal funding.

Fewer complaints proceeded to an investigation under the Trump administration

The resolution code analysis above found that few allegations are investigated by the OCR. However, the data also show a marked difference in the percentage of allegations that were investigated during the past two administrations. All complaints with the resolution type “no violation or insufficient evidence” and some complaints with the resolution type “closure with change” involved an investigation by the OCR. Accordingly, using upper- and lower-bound estimates, the OCR was between 54 percent and 356 percent more likely to investigate a SOGI-related complaint under the Obama administration than it was under the Trump administration.29

Secretary DeVos is failing her duty to enforce civil rights for all students

Secretary DeVos has made clear her disregard for the safety and well-being of LGBTQ students, both in her public remarks and the policies she has advanced during her tenure. At a congressional hearing on April 10, 2019, Rep. Suzanne Bonamici (D-OR) asked DeVos if she had known about the alarming levels of suicide among transgender students when she rolled back Title IX guidance. Secretary DeVos simply responded that she was “aware of that data.”30

The present analysis examines her approach’s impact on the resolution of complaints filed with the OCR by LGBTQ students.

The data clearly show that the OCR is failing to take action to protect the civil rights of LGBTQ students. The data provided to CAP show a significant decrease in the rate of corrective action under the leadership of Secretary DeVos—far fewer complaints resulted in an OCR-mediated resolution between parties, an agreement requiring change, or the school taking action to correct its policies or practices as a result of the OCR’s involvement. Even under the Obama administration, most complaints submitted to the OCR were dismissed or closed without any corrective action. However, only 2.4 percent of complaints resulted in corrective action under the Trump administration—nine times lower than the rate under the Obama administration.

The data provided are not detailed enough to infer the cause of this decrease, but the inaction around civil rights for SOGI-related complaints is in line with public actions taken by the department. The February 2017 rescission of guidance on transgender students sent a clear signal about the lack of protection. Moreover, a rule proposed in November 2018 would disincentivize sexual harassment reporting and drastically reduce school liability under Title IX, for example, by changing the definition of sexual harassment, introducing burdensome reporting requirements, and allowing schools to proactively disregard certain Title IX protections by claiming religious exemptions. As outlined previously, in 2018 DeVos announced that her department would no longer investigate complaints filed based on gender identity discrimination; and in a 2019 hearing, she refused to specifically address questions about suicide rates among transgender students.31 All students, including LGBTQ students, deserve to have their civil rights recognized and protected. However, the dramatic decrease in corrective actions for SOGI-related complaints suggests that the OCR is falling short of its duty.

As previously outlined, allegations in the dataset were most commonly dismissed or closed because the OCR did not receive a consent form, the allegations were not timely, the complaint was withdrawn, or the complaint was in litigation or being investigated elsewhere. Unfortunately, for students living in parts of the country with no protections under state or local law, litigation may be their only option. As noted in a past CAP study on health care discrimination complaints submitted to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, litigation can take longer to arrive at a resolution and can be more costly for both parties.32 By contrast, an administrative resolution facilitated by the OCR can result in a timely resolution that is agreeable to both parties and can provide necessary technical assistance to recipients to help them come into compliance with Title IX.

An effective civil rights enforcement process should involve investigations even in cases where the recipients are in compliance with statutory requirements. The overall decrease in the rate of SOGI-related complaints resulting in an investigation is in itself a cause for concern, as it suggests that the OCR no longer prioritizes the civil rights of LGBTQ students. Notably, under the Trump administration, the rate of complaints that resulted in a finding of no evidence of noncompliance with Title IX following an investigation was half that of the Obama administration. While actions taken by the Obama administration to protect LGBTQ students were criticized as overreach, Obama’s OCR was actually more likely to find no evidence of wrongdoing than that of the Trump administration. Indeed, a recent release of select data by the OCR reinforces this pattern of neglect. While Assistant Secretary for Civil Rights Kenneth Marcus claimed in a July 2019 press release that “instead of seeing every case as an opportunity to advance a political agenda, [the OCR is] focused on the needs of each individual student and on faithfully executing the laws,” his claim is countered by the very data published in the release.33 Author analysis of the data shows that the rate of civil rights complaints that were resolved with a change benefiting the student actually decreased from 13.0 percent to 10.8 percent from FY 2009–FY 2016 compared with FY 2017–FY 2018.34 Unfortunately, up until this report, the July 2019 press release contained the entirety of civil rights data made available to the public under the Trump administration. Moreover, since the OCR has not published any annual reports on its enforcement activities, it is not possible to disaggregate the data to specifically analyze sexual- or gender-based harassment complaints—or even all Title IX complaints.

Recommendations

To ensure that all students have equal access to education and a learning environment free from harassment and discrimination, members of the legislative and executive branches at both the state and federal levels must take action.

Reissue Department of Education guidance affirming that Title IX protects all students from harassment and discrimination

Numerous courts have already articulated these protections, and the administration’s attempts to undercut those clear rulings create confusion for schools and students, which leads to poor outcomes. Reissuing guidance that reflects the overwhelming body of case law and clarifies that anti-LGBTQ discrimination is prohibited would ensure that schools understand their legal obligations and that students and families understand their rights.

Issue updated technical assistance and training materials

Reissued guidance should be accompanied by updated technical assistance and training materials that explain and reinforce that Title IX protects students from harassment and discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity. This would ensure that Department of Education staff are aware that their jurisdiction extends to those allegations. Such materials should also acknowledge that LGBTQ students report being disproportionately victimized by sexual and gender harassment compared with their non-LGBTQ peers. Furthermore, increasing the informational resources available to educational institutions is a vital step both in making sure that they understand their responsibilities under Title IX and in helping them come into compliance after committing a violation.

Increase the budget request for and the number of FTE employees at the OCR

According to the Department of Education’s own 2020 budget summary, from FY 2007 to FY 2018, the number of complaints that the OCR received doubled, and yet, the number of investigative staff decreased by 10 percent.35 Lower caseloads for those monitoring alleged civil rights violations may lead to more thorough investigations and better outcomes for complainants. A larger budget would provide compensation for these additional employees and ensure that they have the resources they need.

Pass the Equality Act

The Equality Act of 2019 would update existing federal civil rights protections by adding protections against sex discrimination to Title II (public accommodations) and Title VI (federal funding) of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, modernizing what constitutes a public accommodation for all classes protected by Title II and explicitly clarifying that existing protections against sex discrimination include sexual orientation and gender identity.36 Areas with existing protections include employment, housing, credit, and jury service. While the Equality Act does not amend Title IX, the inclusion of sexual orientation and gender identity protections in federal funding would add explicit protections for LGBTQ students.

Pass the Safe Schools Improvement Act

The Safe Schools Improvement Act (SSIA) would require school districts in states that receive Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) funds to enact policies that prevent and prohibit bullying and harassment. These policies would need to incorporate explicit bans on bullying and harassment on the basis of several enumerated characteristics, including a student’s actual or perceived sexual orientation or gender identity and the actual or perceived sexual orientation of someone with whom the student associates.37 The SSIA would also require biennial evaluation of and reporting on bullying and harassment rates.38

Pass state-level student nondiscrimination and anti-bullying laws that enumerate SOGI

Nearly half of the LGBT population lives in states with no state laws protecting LGBT students from discrimination, and 41 percent live in states that lack laws protecting LGBT students from bullying on the basis of SOGI.39 States need additional nondiscrimination and anti-bullying education laws explicitly prohibiting discrimination or bullying based on sexual orientation and gender identity in order to bolster Title IX’s existing protections and make them easier to enforce. State laws that explicitly protect against bullying and discrimination based on SOGI have been associated with fewer youth suicide attempts, for both LGBTQ and non-LGBTQ youth.40 Such laws also have public support, with one poll finding that 83 percent of parents support anti-harassment and anti-discrimination laws that fully enumerate sexual orientation and gender identity.41

Conclusion

Secretary DeVos has a duty to ensure equal access to education for all students. It is the responsibility of the Department of Education to protect the rights of the youth in its care, including those who are LGBTQ. DeVos’ Department of Education is failing in that statutory duty. Rather than rolling back the clock on civil rights, the department should acknowledge the specific needs of LGBTQ students, make clear that they are protected under Title IX, and meaningfully pursue complaints filed by students and families who seek to exercise those rights.

About the authors

Shabab Ahmed Mirza is a research assistant for the LGBT Research and Communications Project at the Center for American Progress, where she works on homelessness and housing policy; data collection on sexual orientation and gender identity; and the impact of anti-LGBTQ discrimination. Her work has been cited in Time, Forbes, NPR, and other publications. Previously, she worked at the National Center for Transgender Equality and was a Young Leaders Institute fellow at South Asian Americans Leading Together. Mirza received a bachelor’s degree from Reed College and an associate degree from Portland Community College. She is from Dhaka, Bangladesh.

Frank J. Bewkes is a policy analyst for the LGBT Research and Communications Project at the Center for American Progress. He leads state-level engagement for the team and focuses on LGBTQ family law and policy. Prior to joining the Center, he worked for such organizations as the American Civil Liberties Union, the Family Equality Council, the Congressional Coalition on Adoption Institute, and the Brennan Center for Justice. Bewkes holds a Master of Laws from New York University School of Law and a J.D. from George Washington University Law School, where he was awarded the Thurgood Marshall Civil Liberties Award. He earned his Bachelor of Arts in political science at Yale University. He is also currently an adjunct professor at Georgetown University’s McCourt School of Public Policy.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank GLSEN and the National Center for Transgender Equality for reviewing and providing feedback on this report.

Most especially, the authors thank the following individuals, who significantly contributed to the research, drafting, and/or review of this report: Laura E. Durso, Sharita Gruberg, Charlie Whittington, Adam Cetorelli, Gabriel Lewis, Mia Aassar, Sarah Kellman, Emily London, Maggie Siddiqi, Osub Ahmed, Victoria Yuen, Jessica Yin, Brenda Barron, Joe Kosciw, Ma’ayan Anafi, and Harper Jean Tobin.

Appendix: Data analysis and methodology

To learn more about anti-LGBTQ discrimination in education and the Department of Education’s enforcement of Title IX protections for LGBTQ people, CAP submitted FOIA requests to the department on January 24, 2017; June 16, 2017; and February 15, 2018. The first request asked for complaints of discrimination since October 1, 2010, based on gender identity, sexual orientation, and sexual orientation-related sex stereotyping under Title IX. The second FOIA request asked for the same categories of complaints from January 24, 2017, to June 16, 2017, while the third asked for such complaints since January 20, 2017. Collectively, the information provided to CAP in response to the three FOIA requests contained complaints based on gender identity, complaints alleging gender harassment, and complaints alleging gender stereotyping-related sexual harassment—all of which were filed with the OCR from March 31, 2010, to May 21, 2018. While all of CAP’s FOIA requests requested the same information, the three batches of data did not contain the same variables.

The data provided to CAP included the following variables:

- Docket number: Each complaint is assigned a unique identification number called a docket number. A single complaint can encompass multiple records, for example, if there are two or more allegations of discrimination. For this reason, multiple rows of data could contain the same docket number since they refer to the same complaint. The OCR generally handles discrimination at each educational institution separately, so all records with the same docket number refer to the same educational institution.

- Recipient name: The educational institution receiving federal financial assistance is referred to as the recipient. The data include complaints filed against K-12 schools, degree-granting colleges and universities, and other educational institutions that receive federal funding, such as vocational schools.

- State/location: The recipient may be in a U.S. state, the District of Columbia, or a U.S. commonwealth or territory.

- Stage: The stage indicates how far along a complaint is in the OCR process. The possible stages of a complaint are “evaluation,” “investigation,” “negotiation,” “enforcement,” “monitoring,” “closed,” and “reconsideration/appeal.”

- Case open date: The case open date is the date a complaint is filed with the OCR.

- Case resolved date: The case resolved date is the date a complaint is resolved by the OCR.

- Case closed date: The case closed date is the date the file for a complaint is closed. Sometimes, a case file may be resolved but not closed—for instance, when the OCR continues to monitor a recipient after an agreement.

- Specific basis: Civil rights complaints are filed based on different classes protected by law. The category to which the complainant belongs is indicated by the specific basis—for example, “discrimination against males” or “transgender/gender identity.”

- Issue code: When a Title IX sex discrimination complaint is filed, it is assigned an issue code that specifies the nature of the alleged discrimination—for instance, “gender harassment,” “discipline,” or “retaliation.” Since a single complaint may contain multiple allegations of discrimination, it may include multiple issue codes.

- Resolution code: The OCR evaluates each allegation of discrimination independently. The resolution to a specific allegation of discrimination is indicated by a resolution code. Since complaint issue codes may have different resolution codes, a single complaint may contain multiple resolution codes. The second and third datasets did not contain resolution codes.

- Resolution type: Once all issues are resolved, the OCR assigns each complaint a resolution type, which indicates the highest level of action taken in response to the complaint. Each resolution code is grouped under 1 of 6 resolution types: “dismissal,” “administrative closure,” “early complaint resolution,” “insufficient evidence of noncompliance determination,” “closure with change” (a resolution agreement or some other resolution resulting in a benefit to the alleged injured party), or “violation with enforcement” (administrative or judicial proceedings). For example, a complaint may include separate allegations of gender harassment and retaliation. In such cases, the OCR may refer the allegation of retaliation to the EEOC, which is categorized under “administrative closure,” and enter into a resolution agreement to address gender harassment, which would be considered a “closure with change.” Since the resolution agreement is the most severe response by the OCR, the complaint would be assigned the resolution type “closure with change.” The second dataset did not contain resolution types.

- Investigation date: The investigation date is the date a complaint is opened for investigation by the OCR.

The data provided to CAP contained a total of 727 records. Assuming that the most recently provided information was the most accurate, 64 duplicate records were deleted. However, the authors retained information that was only available in the deleted records for specific complaints—for example, resolution codes and recipient names. After cleaning the data, there were 573 unique complaints from the three sources combined.

A single complaint could have multiple records to list different specific bases, issue codes, or resolution codes/types, so the authors constructed separate spreadsheets for analysis based on unique specific bases, issue codes, and complaints in order to avoid duplicates depending on the unit of analysis. For example, a complaint could list two specific bases but only one issue code, so the spreadsheet for analysis by issue code would delete the duplicate, whereas the spreadsheet for analysis by specific basis would retain both records.

The main variables of interest were issue code, resolution type, and case open date. Additional variables were created for specific analyses:

- Case open fiscal year: The fiscal year in which a complaint was filed, based on the case open date

- Case resolved fiscal year: The fiscal year in which a complaint was resolved, based on the case resolved date

- Case open presidential administration: The presidential administration during which the complaint was filed, based on the case open date

- Case resolved presidential administration: The presidential administration during which the complaint was resolved, based on the case resolved date

- Sexual or gender harassment: A binary variable indicating whether a complaint contained any allegation of sexual harassment or gender harassment

- Religious affiliation: A binary variable indicating whether a recipient clearly stated a religious affiliation on their website (see text box on “Religious affiliation”)

In addition to the data provided to CAP by the OCR, further analyses were conducted using publicly available information:

- The authors consulted websites for the recipients to assess whether they had a religious affiliation.

- An archived page on the Department of Education website listed all requests for religious exemptions and the department’s responses from 2009 to 2016.42

- The authors examined the OCR’s reports to the president, which contain summary data on complaints filed with their office. These reports are not necessarily published annually; the four reports that overlap with the current time period of analysis are for the following time periods: FY 2009–FY 2012, FY 2013–FY 2014, FY 2015, and FY 2016. No reports were published in FY 2017 or FY 2018.

Religious affiliation

One of the foundational principles of the United States is ingrained in the First Amendment to the Constitution: Congress cannot make any law “respecting an establishment of religion.”43 This principle of religious liberty should extend to all. However, it has increasingly been exploited to favor the interests of a select few over the basic rights of others—particularly marginalized groups such as women, pregnant individuals, people of color, religious minorities, and LGBTQ people.44

In this analysis, recipients who described themselves as having an affiliation with a religion or faith tradition were coded as religiously affiliated. A broad definition of religious affiliation was used to capture as many institutions in the dataset as possible. As such, the educational institutions coded as having a religious affiliation vary considerably in the ways that they put their faith-based values into practice. They include:

- A liberal arts college that maintains a religious affiliation even though its student body and employees may come from any faith background

- A seminary designed to train students for a career as members of the clergy or other religiously-affiliated professions

- A university affiliated with a particular religion that primarily educates students of its own religious background but also has schools of law, medicine, or other programs that admit students on a competitive basis regardless of their personal connection to that religion

The analysis excluded institutions with historic religious affiliation that have since formally ended any such connection. For example, one college in the dataset was founded as a seminary but, on its website, clearly states that it is no longer religiously affiliated, so it was not coded as having a religious affiliation.

There may be significant variation in the ways in which religiously affiliated institutions address discrimination based on gender identity, sexual orientation, and sexual orientation-related sex-stereotyping depending on how they practice their faith. However, the present analysis groups them together since they all are eligible to seek exemptions from federal nondiscrimination rules based on their religious affiliation.

Few civil rights agencies explicitly collect SOGI-related data from complainants, one of the many barriers to obtaining accurate disaggregated LGBTQ data at the federal level. Currently, LGBTQ complainants can only be identified if their allegations of discrimination are related to their identity. Since the OCR does not publish statistics on the number of SOGI-related complaints, the records provided to CAP were assumed to account for all SOGI-related complaints.

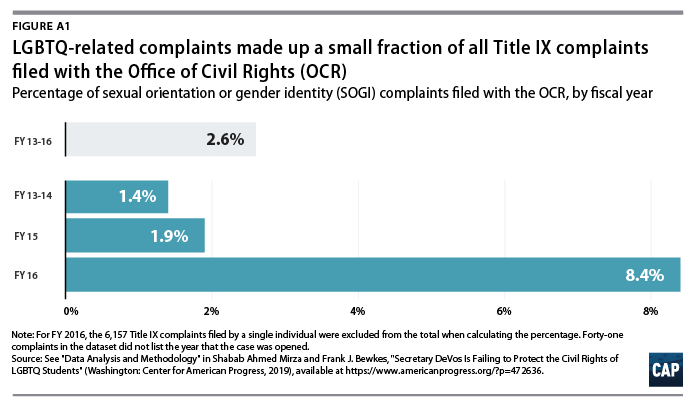

Complaints alleging SOGI-related discrimination usually comprise between 1 and 2 percent of all complaints received each year. (see Figure A1) The one exception is FY 2016, when the departments of Education and Justice released their joint guidance on the rights of transgender students, which may have led to the increase in SOGI-related complaints. Greater clarity on Title IX protections for transgender students may have encouraged more students to come forward with their complaints.

It is important to note that the percentages of LGBTQ complaints do not reflect the number of LGBTQ complainants. For example, a lesbian may experience discrimination based on her identity as a woman. Accordingly, she may file a complaint of sex-based discrimination, but it may not appear in the records since the discrimination is unrelated to her LGBTQ identity.