Introduction and summary

For nearly 16 years, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) Office for Civil Rights and Civil Liberties (CRCL) has worked to protect individual liberties and the promise of equal treatment under the law. In the face of unprecedented challenges to individual rights and basic constitutional norms that have taken place throughout the Trump administration, the time has come for Congress to re-evaluate CRCL’s authorities, independence, and transparency. Reforms will give the agency better tools to ensure more meaningful oversight and lay the groundwork for the DHS to be both more effective in its security objectives and more respectful of American constitutional values in the future.

In 2002, Congress and the Bush administration rebuilt the federal approach to immigration and domestic security by pulling dozens of offices and agencies out of their institutional homes and bolting them together as the new DHS.1 Amid hysteria in the immediate wake of 9/11, the U.S. Department of Justice2 (DOJ) carried out widespread illegal and abusive detention of Muslim and Asian immigrants; police and private actors engaged in aggressive and even violent racial profiling;3 and the public had growing concerns about overreach in the USA Patriot Act.4 Recognizing these problems, Congress formed an innovative new office within the DHS: CRCL. According to CRCL, the office “supports the Department’s mission to secure the nation while preserving individual liberty, fairness, and equality under the law.”5

Throughout the Bush and Obama administrations, CRCL grew to play an important—if frequently circumscribed—role in making the DHS more transparent and responsive on critical issues, including surveillance, disability accommodation, language access, and respect for the rights of arrested and detained immigrants. The Trump administration’s actions, however, have exposed long-standing limits on CRCL’s ability to meaningfully fulfill its mission in the face of political leaders who continuously aim to violate the U.S. Constitution. CRCL’s limitations became abundantly clear in the first weeks of 2017, with the discriminatory travel ban put in place for millions of Muslims, and again in 2018, with the shameful and purposeful separation of children from their parents at the southern border.

Sixteen years after CRCL began operating, it is time for Congress to strengthen the authorities that make the office effective and transparent. This report recommends specific legislative and policy changes that will ensure CRCL can better perform its necessary role. The recommendations fall into three broad areas:

- Authority: Congress should give CRCL clearer statutory authorities with regard to its investigations and policy recommendations, including a clearer requirement that it be involved in policy development; firm timelines for responses to its recommendations inside the DHS; and subpoena power over third parties whose interactions with the DHS are alleged to violate civil rights and liberties.

- Independence: Congress should ensure that CRCL has independent legal counsel and sufficient operational independence within the DHS. CRCL should also have reporting authority over civil rights officials inside each of the DHS’s main operational components.

- Transparency: Congress must demand that CRCL be more transparent with people who file complaints with the office and ensure that it can make meaningful, independent reports to Congress and the public on its activities as well as the DHS’s responses to its recommendations.

CRCL’s history and statutory mandate

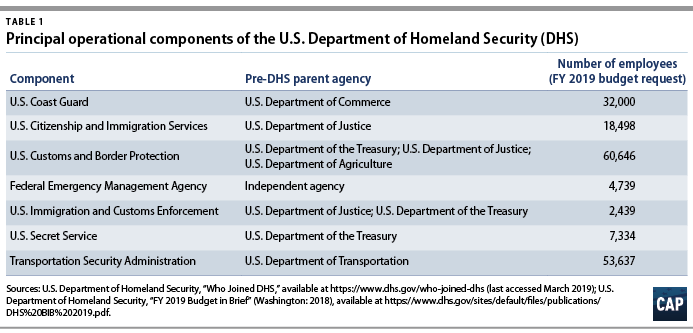

The Homeland Security Act of 20026 structured the DHS on the model of the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD), with the lion’s share of its employees in largely autonomous operational components and an assortment of smaller offices and agencies7 all coordinated by a comparatively small DHS headquarters. (see Table 1) At the urging of national civil rights and liberties advocacy groups, Congress recognized that antiterrorism, border security, and immigration administration and enforcement presented unique challenges to ensuring that core constitutional values are realized. CRCL was thus created as an office within DHS headquarters, with a presidential appointee leading a career staff and reporting to the DHS secretary.8 CRCL’s authorities were then clarified and expanded in the Homeland Security Civil Rights and Civil Liberties Protection Act of 2004, which added to the DHS’s core mission that it, “ensure that the civil rights and civil liberties of persons are not diminished by efforts, activities, and programs aimed at securing the homeland[.]”9 The Implementing Recommendations of the 9/11 Commission Act of 2007 provided additional authorities to CRCL and its sister privacy and civil liberties offices within other federal departments, including cooperation with and reporting to the U.S. Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board (PCLOB) created by the same legislation.10

As a result, CRCL’s mandate from Congress now includes three primary modes of operation as a policy and oversight office:

- First, as a policy adviser, CRCL is to “review and assess information concerning abuses of civil rights, civil liberties, and profiling on the basis of race, ethnicity, or religion, by employees and officials of” the DHS; “assist the Secretary, directorates, and offices of the Department to develop, implement, and periodically review Department policies and procedures to ensure that the protection of civil rights and civil liberties is appropriately incorporated into Department programs and activities;” and “oversee compliance with constitutional, statutory, regulatory, policy, and other requirements relating to civil rights and civil liberties.”11

- Second, as an investigator of outside complaints about specific violations, CRCL, in coordination with the Office of Inspector General (OIG), is to “investigate complaints and information indicating possible abuses of civil rights or civil liberties.”12

- Third, as a communications and interface office, CRCL is charged to “make public … information on the responsibilities and functions of, and how to contact” the office.13 It is a function that has in practice encompassed a broad array of engagement with stakeholder communities ranging from Washington-based advocacy organizations to community-based political, ethnic, religious, and cultural organizations.14

Most federal civil rights offices focus on preventing and addressing discrimination in the workplace and among grant recipients15—functions that CRCL also performs. CRCL’s statute is unusual in setting it up as a form of internal oversight over ongoing and contemplated policies and programs—a function that dominates the day-to-day work of most CRCL staff. The result is an entity unlike any other federal agency’s civil rights office, in that CRCL’s principal role is in influencing and investigating policy development within the DHS as well as official actions taken by federal employees rather than assuring compliance with rules and standards by outside entities in regulated industries.16

CRCL’s policymaking role

Since its founding, CRCL has expanded substantially and found enduring influence in certain policy areas that regularly confront DHS decisionmakers. For example, CRCL has issued important DHS-wide policies that protect the privacy of domestic violence victims and ensure disability accommodation.17 The office has played a significant behind-the-scenes role in immigration enforcement and detention reforms: When a CRCL-contract pediatrician recognized that an infant being held in a family detention center nearly died of dehydration, that unsafe facility closed in 2014.18 CRCL has also been involved in developing limitations on U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s (ICE) use of solitary confinement—or what the agency calls “segregation.”19

In a federal agency’s ordinary policy development process, an initiative could come from the top down such as from a president or Cabinet secretary and her political staff; percolate up from the bureaucracy of the agency; or be required by Congress or a judicial decision. Policy development is generally owned by one part of an agency, but other elements with appropriate technical knowledge will be brought in to consult and advise. For example, at the DHS, the Office of the Chief Financial Officer is called upon to help determine resources; the Office of the Chief Information Officer is called upon to plan a database system; and the Office of the General Counsel is called upon to address general legal issues. Congress’ innovation with CRCL was to set up a dedicated office that, in an ordinary policy development process at the DHS, would be included wherever a policy could touch on civil rights and civil liberties issues such as racial profiling, humane detention standards, or free expression. While this process is often carried out behind the scenes, it regularly comes into view in a final policy document. In 2017, for example, the DHS implemented a new legislative requirement to allow DHS entities to capitalize on DOD training missions. Recognizing the potential for civil liberties concerns, CRCL coordinated with other DHS offices to ensure that each such training mission would be subject to a civil rights and civil liberties review, with CRCL available to provide ongoing expert assistance.20

The DOD training missions are an example of successful policy development. However, even during the Bush and Obama administrations, CRCL’s ability to access information or to affect outcomes was often sharply limited. Even in a less fraught political atmosphere, observers of CRCL noted substantial civil rights and civil liberties problems that CRCL seemed unable to address, including:

- A pervasively unsafe and inappropriate civil detention system managed by ICE that places many noncriminal detainees in county jails and other jail-like institutions under inadequate standards and at high risk of sexual assault21

- Unacceptable levels of death, including in particular deaths by suicide, in those institutions22

- Inadequate inspections and oversight of detention facilities23

- Discrimination on the basis of sex, sexual orientation, and gender identity in the placement of detainees in immigration detention facilities24

- Inability to respond effectively when DHS personnel enable or facilitate racial and ethnic profiling, including by state and local law enforcement agencies25

- Episodes of excessive use of force in the apprehension of suspected noncitizens and in cross-border shootings26

If CRCL’s ability to be effective was in question under previous administrations, its marginalization has manifested in the Trump administration. Two episodes of course stand out: the unlawful attempt to impose religious discrimination against Muslim immigrants beginning in January 2017 and the remarkably damaging policy of separating migrant children from their families as a general deterrent to asylum-seekers at the southern border.27 Public accounts make clear that CRCL had no meaningful role in the formulation or, perhaps worse, the implementation of those policies, even though it would have been clear to any reasonable official that the initiatives involved the office’s area of expertise: international humanitarian treaty obligations, the substantive due process rights of parents, the appropriate standards for detention of vulnerable populations, the communication of critical information across language barriers, and more.28

Policies driven directly by the White House—such as the president’s anti-Muslim immigration initiative—are bound to be less amenable to a bureaucratic policy office’s interventions than more routine issues. As Margo Schlanger, former head of CRCL, stated:

CRCL … can ring warning bells and offer expert assistance about civil rights risks and solutions. But without an extraordinary degree of empowerment, CRCL might slow but could not stop a Department unconcerned about effectively orphaning hundreds of migrant children, disinterested in safe detention, or dead set on Islamophobic screening protocols.29

The challenge for Congress may not be to ensure that CRCL can stop the next family separation crisis but to give it the authority and tools it needs to play its best role in more ordinary cases. And, just as importantly, Congress should ensure that the office can at least effectively sound the alarm within the department as well as for Congress and the public in those more extraordinary circumstances.

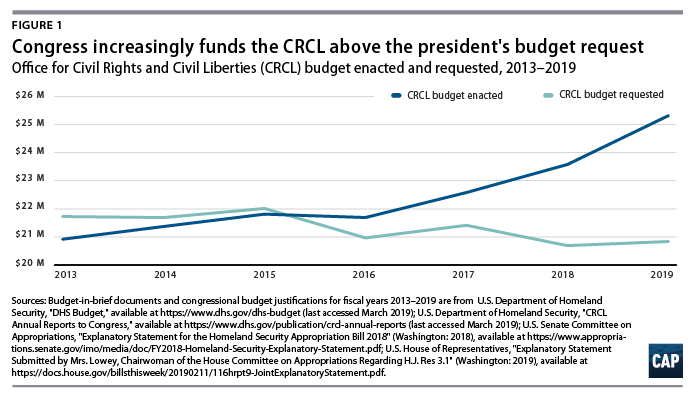

The marginalization of CRCL in recent years within the DHS and the executive branch more broadly is at odds with Congress’ repeated interest in increasing the office’s funding to bolster civil rights and civil liberties oversight within the DHS. Beginning in fiscal year 2016, under both the Obama and Trump administrations, Congress appropriated more funding than was requested to support CRCL. (see Figure 1)

CRCL’s ongoing challenges in structure and authority

The Center for American Progress recognizes that no obscure policy office would be able to stop a DHS secretary who is bent on adopting child abuse as a government program or defying the plain language of the asylum statute.30 CAP therefore focuses on ongoing, institutional problems that predate the current administration and would remain under its eventual successors. Experience has shown that with its current statutory authorities and structure within the DHS, CRCL suffers from the following shortcomings and limitations.

Inability to ensure access to information or responses from DHS component agencies

As noted, CRCL received no information prior to the DHS implementing its effort to bar people from the United States based on their religion, and it struggled to obtain basic information about family separation—even when that information was being shared directly with the media. These high-profile examples reflect a larger failure of CRCL to have full visibility into policy initiatives that carry substantial civil rights or civil liberties consequences. Except in the few cases where a directive or regulation has expressly required CRCL’s involvement,31 DHS processes frequently leave CRCL in the dark until an action has progressed too far to be brought into compliance with civil rights and civil liberties requirements.32 The office is generally reliant on the internal departmental clearance process, which is administered by the DHS Office of the Executive Secretary, to circulate important documents for signoff by each affected agency and office within the DHS.33 With the breakdown of an orderly policymaking process under the Trump administration, however, many critical policy documents never pass through that process, and CRCL is often not included in the circulation of the most sensitive policy documents.34

Whether the issue is a failure of other policymakers to appreciate the civil rights dimension of a problem—as can frequently be the case when it comes to accommodating disabilities or language needs—or an intentional choice to exclude civil rights experts from decision-making processes, the result is the same: CRCL is left out of the loop. A similar problem has been addressed through the Privacy Act of 1974 and the E-Government Act of 2002, under which agencies are required to regularly perform a privacy threshold analysis to determine whether a record system requires privacy analysis—and if so, a privacy impact assessment to determine privacy risks and mitigation steps.35 CRCL has no equivalent process to force component agencies to surface or disclose impending policy decisions with a civil rights or civil liberties dimension.

A related problem arises in CRCL’s complaint investigations, where no mandatory timeline governs component agency responses to CRCL, whether they be requests for information or final recommendations. CRCL and component agencies have negotiated turnaround time agreements, but these are frequently ignored in practice, leading to lengthy delays in resolving complaints.36 And when CRCL and a component agency disagree, there is no formal process for escalating the dispute to be resolved at the secretary level. This pitfall was made clear when a dispute between CRCL and ICE over a case of U.S. Border Patrol (USBP) complicity in ethnic profiling came to light due to an inadvertent record disclosure during the Obama administration.37

Because Congress has generally kept CRCL from having direct remedial authority, it must work through the operational component agencies from which particular forms of relief are available. This makes it all the more important that CRCL be able to demand a timely response, seek resolution of a dispute, and keep Congress and the public informed. Experience in the one domain where CRCL does have some remedial power—that of disability accommodation—shows that the operational component agencies are not hindered by a CRCL that has the ability to require genuine redress.38

Clearer statutory language setting forth CRCL’s need for information and to reach an ultimate resolution would give the office the tools it needs to address these shortcomings—as will a clearer expectation that CRCL will report to Congress and the public when it has and has not been given an appropriate seat at the table in DHS’s most important conversations.

Insufficient and late reporting on complaint investigations and other office activities

CRCL’s transparency needs to be greatly improved. As it stands now, neither the people and organizations that file civil rights complaints nor Congress and the general public can glean a clear understanding of CRCL’s effectiveness or where the DHS is freezing it out.

Each year, CRCL receives hundreds of complaints, many of which are lengthy, well-researched, comprehensive documents filed by professional advocacy organizations.39 Others are individual complaints filed by ordinary people who believe that they were discriminated against in an interaction with the DHS. Across the board, however, complainants generally receive little information on the outcome of their complaints.40 This paucity of information is particularly striking when contrasted with the detailed, often public reports that the OIG releases—including in cases where both the OIG and CRCL conducted an investigation.41

In 2019, Congress directed CRCL to ensure that complainants receive more information within 30 days of the end of each complaint investigation. If history is any guide, however, the DHS will continue to shield meaningful information about complaint outcomes behind claims of deliberative-process and attorney-client privilege notwithstanding this provision.42 While privacy issues limit what CRCL can make available to the public, Congress could require CRCL to send confidential copies of all final recommendations to the relevant congressional oversight committee.

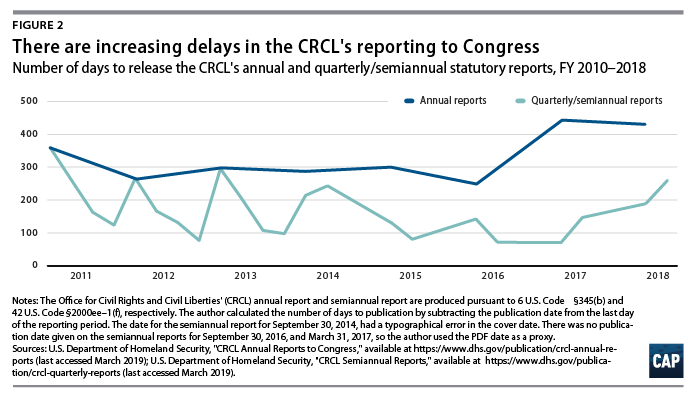

Currently, CRCL has two existing statutory reporting requirements: an annual report that the DHS secretary sends to Congress43 and a semiannual report from CRCL to both Congress and the PCLOB, an independent body that reviews and makes policy recommendations on national security civil liberties issues across government.44 During the Trump administration, these reports have become exceptionally late, with the past two annual reports coming more than one year after the end of the year to which they pertain.45

Moreover, the reports themselves are far less informative than they could be. When it comes to reporting the results of complaint investigations, they fall short of describing any particular findings or recommendations. For example:

- A report on preventing suicides among individuals in U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) custody stated: “Our subject-matter expert drafted an expert recommendations memo for CBP and Border Patrol … CRCL will also work with CBP to implement our expert’s recommendations to the greatest extent possible.”46 What suicide risks were present in CBP custody—and the recommendations to prevent them—were not discussed in the report.

- A report on providing religious diets to migrants locked in ICE detention noted that CRCL reports having receiving “numerous complaints … regarding ICE’s accommodation of religious dietary requirements,” about which it made unspecified recommendations in October 2016. Four months later, “ICE agreed that requests for religious meals should be accommodated”—a basic constitutional right for all detainees—“however, it did not concur with other CRCL recommendations in this area.” The report gives no indication of on what issues ICE and CRCL disagreed.47

- In a report on deaths and suicides in ICE detention, CRCL stated that it made 25 recommendations—in 23 of which ICE concurred—following four deaths (two of them suicides) at a single Arizona detention center. However, not one of the recommendations is described in the report.48

Summaries such as these do not convey whether CRCL truly identified a civil rights problem or whether the DHS responded or stonewalled the office. Other statutory language requires that CRCL regularly report “the type of advice provided and the response given to such advice.”49 A review of these reports makes clear that CRCL is not reporting—or the report’s reviewers in the DHS secretary’s office or the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), as discussed below, are not allowing it to report—circumstances in which its advice is disregarded or excluded from policy development. Again, no instance could make the problem clearer than the lack of any reference being made to CRCL’s exclusion from the implementation of the Muslim travel ban in the office’s report from that year.

In yet another example, the FY 2017 CRCL report issued in November 2018 stated that CRCL was still “reviewing the ICE response” to a recommendation memo CRCL had sent to ICE in August 2016. If this response is further described in the upcoming FY 2018 annual report, it will have been more than three years since CRCL issued whatever its recommendations were when the public finally receives that information. Furthermore, the FY 2017 report fails to describe even in general terms what those 2016 recommendations were or how ICE responded.50

These delays in reporting are attributable to many causes: delay by DHS component agencies in responding to CRCL; arguments about the application of privileges to prevent disclosure; and the agonizing clearance process by which the reports must be approved by CRCL, DHS’s attorneys, the DHS secretary, and the OMB. As a consequence, there is diminishing reason for complainants to have faith that CRCL’s investigations are producing better observance of civil rights and civil liberties.

Two other oversight offices in DHS headquarters—the DHS Privacy Office and the Citizenship and Immigration Services Ombudsman—have much stronger independent reporting mandates than does CRCL. While the DHS secretary reports CRCL activities to Congress, those other offices “submit reports directly to Congress … without any prior comment or amendment by the Secretary, Deputy Secretary, or any other officer or employee of the Department or the Office of Management and Budget.”51 Independent reporting is critical to ensure that CRCL can accurately disclose if the secretary refused its recommendations, precluded it from exercising its statutory authorities or otherwise inhibited its effectiveness.52

Lack of independent legal counsel to stand up to DHS component agencies

CRCL’s statutory mandate includes “oversee[ing] compliance with constitutional, statutory, regulatory, policy, and other requirements.”53 These functions essentially concern legal issues: determining whether a proposed ICE enforcement action or U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) adjudication policy abides by a constitutional or statutory requirement is a job that should be done by a lawyer. While nearly all senior CRCL staff are attorneys, under DHS rules, they are not functioning as lawyers in the sense of providing legal opinions or working in an attorney-client relationship.

When the DHS was first formed, CRCL, like each of the major DHS components, had its own legal counsel—nominally reporting to the general counsel but responsible to CRCL’s political head.54 This remains the structure in ICE, with its Office of the Principal Legal Advisor, or in CBP or USCIS, each of which has an Office of Chief Counsel. But the position of the CRCL chief counsel no longer exists. Instead, CRCL is served by lawyers who are under the direct management of the DHS general counsel, without the independent political and operational alignment with CRCL that component agency counsel have.55 As a result, CRCL comes to internal debates with one arm tied behind its back, facing off with ICE or CBP, which have their own counsel advocating fiercely for that agency’s position, against CRCL and a representative of the general counsel who represents both CRCL and the component agency.56

This barrier is particularly acute when issues involve litigation, as is the case with many immigration issues. With the same counsel handling DHS’s litigation load as advising CRCL, there is little appetite to create records that could haunt the agency in later litigation discovery. The result is an inversion of CRCL’s intended role: Rather than heading off civil rights problems, it has to be kept away from them for fear of substantiating a violation for which the DHS might later be held liable. The solution to this problem is for CRCL to return to a status with independent legal counsel, giving it the means to stand up for itself in both legal analysis and internal legal arguments.

Lack of reasonable tools to include third-party agencies in its investigations

For years, CRCL has been held out as the DHS’s shield against racial profiling, particularly in the Secure Communities and Priority Enforcement Program (PEP) immigration enforcement efforts, which examine fingerprints that state and local law enforcement collected to identify individuals amendable to deportation proceedings.57 But as CRCL has elliptically reported, even when the DHS secretary charges the office to “monitor state and local law enforcement agencies participating in” immigration enforcement, those investigations are hampered by the fact that CRCL itself has no ability to obtain information from nonfederal entities. This lack of authority to subpoena documents or interview witnesses at local law enforcement agencies involved in programs such as Secure Communities sharply limits CRCL’s ability to conduct meaningful investigations of cases where ICE or CBP has collaborated with local law enforcement on a possibly unlawful arrest.

In particular cases, CRCL may have a statutory power to request documents under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.58 But its general lack of third-party subpoena power is particularly striking in comparison with many other oversight agencies across the executive branch, including the DHS Privacy Office.59 Even if the power were seldom used, possession of such a power would enable CRCL to ensure that third-party agencies took its questions seriously and were prepared to cooperate more fully in civil rights investigations.

Influence that is too remote from DHS’s operational agencies

DHS headquarters is a small layer of leadership on top of its vastly larger component agencies—about 1 percent of total department personnel—and CRCL is a miniscule slice of that at just 0.04 percent of the department.60 Most policymaking occurs far from DHS headquarters and is found in the policy and operational arms of ICE, the Transportation Security Administration (TSA), and other agencies. While those agencies generally have small civil rights offices that address employee discrimination matters and move paperwork in response to CRCL requests, they are not under the control or supervision of the CRCL officer, and they do not appear to function as the eyes and ears of CRCL in order to keep up with policy developments within their respective component agencies.61 This contrasts, curiously, with the component agencies’ chief legal officers, privacy officers, and even information technology (IT) officers, which in practice are dual reports to both the head of each agency and to the corresponding DHS headquarters office.62

In 2017, Congress considered addressing this problem by requiring each DHS component agency to appoint a career civil rights and civil liberties officer, who would “serve as the main point of contact for” and “coordinate with” CRCL.63 The bill died in the Senate in 2018. The concept, however, should be revived so that civil rights professionals, with an ethos that reflects constitutional values and a policy alignment with CRCL,64 have a voice in real-time decision-making in each of the component agencies.

Recommendations

Almost all of the structural issues noted above could in principle be addressed through management action by the DHS secretary.65 In light of 16 years’ experience of DHS leadership resisting a more transparent and effective role for CRCL, however, the best course of action would be for Congress to shore up CRCL’s statutory authorities in 6 U.S.C. § 345 in several critical ways.

Authority

- At all times, CRCL should have clear statutory authority to access all policy documents that could pertain to its mission. This would include the kinds of documents that have been withheld in the past, including decision memos for the secretary and leadership of the component agencies and legal memos produced by the various legal offices within the DHS. CRCL should be included on any document clearance process that includes the DHS Office of Policy, whose central role in policy development is respected. The senior civil rights officials in each component agency should also have the same authority within their respective domains. Any deviation from these information-sharing obligations should require the personal decision of a senior appointee such as a component agency head or the deputy secretary.

- CRCL should create a civil rights and civil liberties threshold assessment tool akin to the privacy threshold assessment that would be a routine part of policy planning throughout the DHS and its component agencies. The threshold analysis would identify issues calling for further analysis prior to proceeding. This would serve to ensure that polices with civil rights or civil liberties dimensions are identified early on and allow for expert advice at early planning stages.

- Where CRCL has obtained information through one of these channels, it should be empowered to make recommendations; receive a timely and concrete response from the affected agency; and escalate disagreements with component-agency leadership for ultimate resolution by the DHS secretary. These operations should be backstopped by an effective reporting process, discussed in greater detail below, so that officials understand that CRCL will be obligated to report on the number and nature of cases where its recommendations are and are not accepted.

- Timelines for component agencies to give responses to CRCL’s investigation requests and final recommendations should be fixed and respected.

- Congress should make clear that it is appropriate for CRCL to recommend, even where it cannot require, remedies in individual cases. For example, when a racial-profiling investigation confirms that improper policing likely led to an immigration arrest, CRCL might recommend that ICE or CBP exercise prosecutorial discretion to discontinue immigration charges arising from the unlawful arrest. These remedial recommendations should also be strengthened by a requirement that CRCL’s recommendations and an agency’s response be reported to Congress and, to the extent possible, the public.

- CRCL should have the same third-party statutory subpoena authority as the DHS Privacy Office and many other executive branch oversight bodies.

Independence

- The role of CRCL chief legal counsel should be revived with a good deal of operational independence from the Office of the General Counsel at DHS headquarters—and possibly with a reporting relationship through the legal department of the OIG—and be as independent as the chief counsels of the operational components.

- The DHS general counsel’s ability to preclude CRCL from an area of inquiry should not include general overlap with a subject matter of active litigation. While the interaction between internal oversight and litigation is necessarily complex, CRCL and DHS counsel should be directed to arrive at workable guidelines that do not unnecessarily sacrifice CRCL’s ability to be effective.

- As proposed in the 2017 DHS reauthorization bill, each of the major operational components should have a chief civil rights professional.66 This official—and any office under her—should follow a dual reporting structure that is responsive to both the head of the component agency and the CRCL officer—the structure followed for many other lines of business within the DHS such as IT. The CRCL officer therefore needs substantial input into the hiring and firing of such officers as well as the routine exchange of information and staff resources to ensure that a culture of respect for civil rights and liberties can be fostered throughout the DHS.

Transparency

- CRCL’s annual report should be independent and not a report of the DHS secretary that is cleared by the OMB. Congress should apply the statutory independent reporting language that the DHS Privacy Office and Office of the Citizenship and Immigration Services Ombudsman have to CRCL as well. Congress should also clarify its expectation for the timely filing of the report, for example, at no more than 90 days after the end of each year.

- Congress should require that all final recommendations made in writing by CRCL—whether in response to a policy initiative or a complaint investigation—be made promptly available to the congressional committees of jurisdiction, with suitable accommodations made to protect sensitive personal information.

- CRCL should strive to provide significantly more information to individual complainants than it does now. The 2019 Committee on Appropriation’s explanatory statement that CRCL provide timely responses to complainants should be made permanent. CRCL should be directed to provide, in redacted form as necessary, copies of completed investigation reports to complainants. In doing so, Congress can clarify that the DHS is not to hide CRCL’s completed work behind deliberative-process privilege, attorney-client privilege—as to findings of fact, which cannot be privileged—or a component agency’s failure to give a final concurrence or nonconcurrence with the recommendation in a reasonable period of time.

Conclusion

CRCL has proven a worthwhile experiment in internal oversight and policy governance in a domain where other forms of oversight—whether congressional or judicial—can lack the speed and expertise to provide real-time input and guidance. But the Trump administration’s assault on civil rights, civil liberties, and other constitutional norms has made existing weaknesses in CRCL’s mandate and functioning clearer than ever. Now is the time for Congress and the DHS to revisit its authorities, independence, and transparency, providing more effective oversight now and creating a better foundation for the DHS to abide by its obligations in the future.

About the author

Scott Shuchart is a senior fellow at the Center for American Progress. From 2010 to 2018, he was the senior adviser to the Officer for Civil Rights and Civil Liberties at the DHS, where he worked extensively on immigration enforcement, detention and custody, and border security, with an emphasis on data-driven analysis to identify civil rights and civil liberties violations. While at the DHS, Shuchart led efforts to ensure that ICE’s Secure Communities initiative and other programs respected civil rights and avoided racial profiling. Prior to joining the federal government, Shuchart was a litigator at Altshuler Berzon LLP in San Francisco and Boies Schiller and Flexner LLP in New York. He then taught at the Yale Law School’s Supreme Court Advocacy Clinic from 2008 to 2010. From 2003 to 2004, Shuchart clerked for Judge Marsha S. Berzon on the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Margo Schlanger for her ideas and analysis and Tom Jawetz, Phil Wolgin, and Silva Mathema for their contributions to this report.