Introduction and summary

For years, the United States has been undergoing major demographic changes that are reshaping the makeup of cities, towns, and communities all across the country. Scholars studying demographic change, particularly change tied to immigration, traditionally approach it as an urban phenomenon: first, detailing how immigrants live and work in traditional receiving communities such as New York, Los Angeles, and Boston; second, documenting how so-called new immigrant gateway cities such as Atlanta, Denver, and Charlotte, North Carolina, are experiencing rapid growth in their immigrant populations; and third, exploring the movement of immigrants to suburban areas beyond the traditional urban settings.1 However, less research is dedicated to studying how immigrants who move to sparsely populated rural areas live in those communities and how those communities adapt to these newcomers.

According to current media coverage of rural America, the picture that emerges most often is one of economic decline, deep-rooted despair and resentment, overwhelming support for President Donald Trump and his policies that target immigrant communities. But this surface-level, one-dimensional portrayal belies a much more nuanced reality and overlooks the major positive roles immigrants are playing in rural America as well as the ways in which those significant contributions could be even more impactful.

Economic restructuring, globalization, and most recently the Great Recession have hit America’s rural communities hard, and many rural areas are consistently losing more people than they are gaining through migration or birth.2 This loss of population has brought a string of hardships to rural areas, from school and grocery store closures to the scaling back of essential health care services—including hospital shutdowns. Not all rural communities are experiencing these trends equally, however. In fact, many rural communities are either experiencing a slowdown in their rate of population decline or a resurgence as immigrants and their families, as well as refugees, move into these communities in search of opportunity. In many rural communities, these new residents open small businesses, provide critically needed health care services, and supply labor for meatpacking plants, small manufacturers, dairies, fruit and vegetable farms, and other enterprises. While some rural communities adjust more easily to these demographic changes, others experience conflict, resistance, and sometimes outright anti-immigrant sentiment—adopting shortsighted policies designed to make life harder for immigrants. While the stakes are high and the obstacles daunting, successfully integrating immigrants into America’s rural communities can bring large dividends.

Rural communities are a microcosm of the entire country: A number of them have had trouble adjusting to their immigrant neighbors3, which is reflective of a national undercurrent of anti-immigrant sentiment that has reared its ugly head of late. Understanding lessons learned from the rural experience with immigration during these polarized times is critical. This report illustrates the geography of population growth or decline in rural communities, with a particular attention to changes in the immigrant population. This analysis is followed by a discussion about what happens to communities that experience population decline and aging as well as some of the ways immigrants are helping to mitigate the negative impacts of population decline and, in some cases, putting communities on a path to prosperity. The report focuses particular attention on the economic contributions of immigrants to industries such as meatpacking, agriculture, and health care.

To a great extent, how well rural communities fare depends on how well they adjust to change and on how welcoming residents are to new immigrants.4 This report discusses some of the strategies that several rural communities have utilized to help integrate residents and newcomers and illustrates that many constructive changes do not require significant resources.

The main findings of this report are as follows:

Immigrants are often reversing or mitigating rural population decline

- Among the 2,767 rural places identified in this report, the adult population declined 4 percent—a combination of a 12 percent decline in the native-born population and a 130 percent growth among immigrants.

- Of these places, 1,894, or 68 percent, saw their population decline between 1990 and 2012–2016. (see methodological appendix for full explanation)

- In 78 percent of the rural places studied that experienced population decline, the decline would have been even more pronounced if not for the growth of the foreign-born population. Without immigrants, the population in these places would have contracted by 30 percent, even more staggering than the 24 percent they experienced.

- In the 873 rural places that experienced population growth, more than 1 in 5, or 21 percent, can attribute the entirety of population growth to immigrants.

Immigrants are leaving a positive mark in rural communities

- As immigrants and their families move to rural communities in pursuit of economic opportunity, they often bring vitality to these places.

- Immigrants provide an indispensable workforce to support communities whose local economies rely on industries such as meat processing plants, dairy farms, or fruits and vegetables farms.

- Immigrants and their families also help local economies in rural communities expand—particularly by opening grocery stores and other businesses that keep their main streets alive and thriving. Kennett Square, Pennsylvania, for example, has prospered with its large population of immigrants, who work primarily in the community’s large mushroom industry and have opened bustling businesses and restaurants.5

- By helping to stave off population decline, a growing immigrant population in rural areas also helps keep schools open and, in some cases, even grows school enrollment.6

- Immigrant health care professionals such as physicians and specialists provide vital care in rural communities that are generally grappling with a shortage of doctors. In many instances, foreign-trained doctors are the only ones providing care in their area, and even then, many travel long distances to see them.7

Takeaways for rural America to integrate their immigrant neighbors

Immigrant integration policies in the United States are localized, leading to divergent approaches and outcomes across communities. Some communities have proactive plans in place to integrate newcomers and allow them to capture the full set of benefits that a thriving and strong community brings. Other communities that initially struggle with their new population later implement policies that help immigrants integrate. Still, some communities have struggled to manage the demographic changes, and local politicians can sometimes worsen these situations by using negative rhetoric or even pushing for anti-immigrant policies that deepen the chasms in the community.

Communities that want to welcome immigrants, increase integration, and harness the benefits should take conscious steps to facilitate civil discussions that involve the whole community. The most critical services for immigrant families often revolve around English language learning, educational access, and social inclusion. Communities that move forward with providing these services and policies often see their immigrant populations prosper. Many of these strategies, which benefit the community as a whole, do not require significant resources to implement.

This report is the first in a series of products exploring the role of immigration in rural America. Focusing on the patterns of change, highlighting the ways in which immigrants are transforming communities, and understanding how communities deal with the challenges of rapid demographic change will not only provide the building blocks to assist rural communities and their new immigrant residents to thrive together but might also provide valuable lessons for the entire nation. In these polarized times, rural places can show the path forward on how best to overcome conflict around demographic change.

Broad demographic shifts in rural America

According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), 72 percent of land in the United States is rural, but it is only home to 14 percent of the total U.S. population.8 Demographic research shows that since 2010, rural America has lost overall population at an alarming pace, only seeing a slight reversal (0.1 percent) in 2016.9

Population shifts in any place can be attributed to two main components: net natural increase, the number of people born minus the number of people who die; and net migration, the number of people who move to and from an area.10 The USDA highlights several factors that contribute to the trend of population loss in rural areas11:

- Young adults have increasingly moved to larger cities, leaving rural communities both smaller and older on average.

- The fertility rate is declining across the United States, including in rural areas.

- Mortality rates are rising at alarming rates among working-age adults in rural areas compared with urban areas, particularly due to the opioid crisis.

- As urban areas across the United States grow and spread, many counties have shifted from a rural designation to an urban designation. Between 1974 and 2016, more than 500 rural counties were redefined as urban or metropolitan, and the remaining rural counties shrank in population—somewhat outside the realm of net natural increase and migration.

While urban, suburban, and other areas shift and grow, John Cromartie of the USDA describes the repercussions of the fewer number of rural counties as “[leaving] behind a smaller rural America made up of slower-growing counties with more limited economic potential.”12 According to Cromartie, a shrinking population can have devastating effects on a rural community, including “a declining tax base, less support for local and small businesses, more retirees in need of health care, and less incentive for young professionals to locate in these areas.” Globalization and the Great Recession have exacerbated these outcomes.13

During the past few decades, many communities have also experienced a transformation in their demographic composition.14 Between 2000 and 2010, increases in the number of people of color—people who do not identify as non-Hispanic white—accounted for nearly 83 percent of the population increase in rural areas.15 An analysis of 2010–2014 American Community Survey (ACS) data found that immigrants in rural communities were more likely to be working-age than were those born in the United States: Nearly 80 percent of immigrants were between the ages of 18 and 64, compared with 60 percent of the U.S.-born population.16 Furthermore, more than 60 percent of immigrants in rural communities arrived in the United States after 1990.17

For rural places, a growing immigrant community can offset the effects of population decline.18 Nationally, immigrants represent 13 percent of the population, up from 8 percent in 1990.19 While at 4 percent immigrants only represent a modest share of residents in rural counties, in 1990, immigrants represented only 2 percent of the total population in these same counties. More than 1 million immigrants moved to rural counties since 1990, and the foreign-born population has a much higher rate of growth than the native-born population in these rural counties—146 percent compared with only 9 percent, respectively.20 Rural counties also saw a higher foreign-born growth rate than their metropolitan counterparts during that time period. In particular, the growth of the Hispanic population in rural places has been well-documented: A study found that between 2000 and 2005, more than 200 nonmetropolitan counties would have lost overall population if new Hispanic residents had not moved to or started families in those counties.21

A primary reason why immigrants move is to pursue economic opportunities. In the 1990s, for example, many rural meatpacking communities such as Schuyler, Nebraska, and Worthington, Minnesota, saw an influx of immigrants because of the abundance of jobs in those towns.22 Unfortunately, rural communities on the whole are uniquely disadvantaged in dealing with such population change. According to James Potter, professor emeritus in the Department of Architecture at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln, and others, “small cities and communities have limited resources to cope with population influx on their housing, infrastructure, and municipal services.”23 Moreover, researchers note that rural communities tend to be less prepared for or have less capacity to deal with cultural change than large cities.24 Real challenges and the potential for conflict exist in rural areas because even a small numerical change in a rural community may seem overwhelming. However, there is also an equal potential for opportunity, and thoughtfully managing these changes may portend meaningful benefits for many of these communities.

Geography of rural communities

While on the whole, the rural United States has faced something between stagnation and population decline, some rural communities have actually seen growth. Studying these places can be illuminating. Past research has focused specifically on the role that growing immigrant communities play in offsetting or reversing population decline across the country. These analyses examined the broader geographic levels such as states, metropolitan areas, and counties. In investigating population change in counties across the United States between 1990 and 2012, a study by the Pew Charitable Trusts documented that as immigrants dispersed across the country from traditional gateways, they offset population declines in a swath of states from North Dakota to Texas and catalyzed growth among the Sun Belt, Pacific Northwest, and Mountain States.25 Similarly, the Chicago Council on Global Affairs found that foreign-born population growth was preventing population decline in metropolitan areas across the Midwest.26

However, using these larger geographies as a unit of analysis can mask local intricacies that are especially important when telling rural stories. The research in this report builds upon those previous analyses by considering the role immigrants play in population change at a very detailed level. It categorizes places based on the shifts in their foreign-born and U.S.-born populations and whether those shifts result in overall population growth or decline when combined.

Defining what is rural

If 100 different people were asked to define what is rural, it is possible that they would give 100 different answers. Even the federal government has multiple ways of determining rurality. Many of these definitions are based on counties, but one designation—the USDA’s rural-urban commuting area (RUCA) codes—is based instead on census tracts.27 Census tracts typically encompass between 1,200 to 8,000 residents; using them in place of counties can help identify rural and urban at a more granular level.28

The methodology that the USDA uses is similar to other analyses that examine immigrants’ contributions to population change at the county- or metropolitan-area level. Tracts are assigned a RUCA from 1 to 10 based on “measures of population density, urbanization, and daily commuting to identify urban cores and adjacent territory that is economically integrated with those cores,” and the Office of Management and Budget’s (OMB) definitions of metropolitan and micropolitan areas.29 RUCAs 1 through 3 identify tracts that are part of metropolitan areas larger than 50,000 people either as part of the urban core or as tracts that send sizable shares of daily commuters to the core, establishing an economic interconnectedness among the tracts. All tracts that are nonmetropolitan are considered rural, though they vary along a scale of rurality. RUCAs 4 through 6 identify tracts that are part of micropolitan areas, or urban clusters with populations between 10,000 and 49,999 people, as well as the surrounding places that are situated within the core’s economic influence. RUCAs 7 through 9 are assigned to small towns with populations between 2,500 and 9,999 individuals and the corresponding places. Completely rural places are those that do not have large numbers of residents commuting to any of the previously mentioned types and are designated by a RUCA of 10.

The U.S. Census Bureau defines and provides data on more than a dozen geographical entities, ranging from the country as a whole to census blocks, from very large and broad to very small and detailed. According to the Census Bureau’s Geographic Areas Reference Manual, a place is “a concentration of population; a place may or may not have legally prescribed limits, powers, or functions. This concentration of population must have a name, be locally recognized, and not be part of any other place. A place is either legally incorporated under the laws of its respective State, or a statistical equivalent that the Census Bureau treats as a census designated place (CDP).”30

Qualifications for analysis

Of the more than 29,000 places in the United States recognized by the U.S. Census Bureau, this study categorizes 2,767 of them based on their rurality, size, and population change from 1990 to 2012–2016.31 It is important to note that 1990 data is from the 1990 Decennial Census, while 2012–2016 data is from the 2012–2016 ACS. Similar to other methodologies examining foreign-born contributions to population growth, this analysis examines population change by nativity for residents who are 18 and older.32 A detailed explanation of all these criteria can be found in the methodological appendix.

This analysis includes places that meet the following criteria:

- The majority of the population lives in census tracts that are designated as nonmetropolitan using the USDA’s RUCA codes.

- At least one resident was foreign-born in 1990, and at least 5 percent of the population was foreign-born from 2012 to 2016.

- The total population was at least 100 residents in both 1990 and from 2012 to 2016.

- Places passed three separate assessments that CAP administered testing their rural or urban assignment based on their census tracts’ RUCA types.

Population change typology

This analysis breaks out rural places into six different typologies based on the components of their population changes from 1990 to 2012–2016:

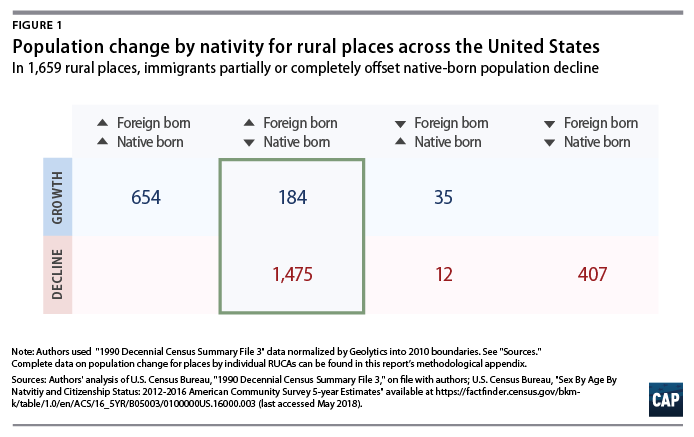

- Rural places with increases in both foreign-born and native-born residents, thus resulting in overall population growth: 654 places

- Rural places that saw growth among foreign-born residents and decline in native-born residents, but with immigrant growth large enough to completely offset the shrinkage, resulting in overall growth: 184 places

- Rural places that saw declines among the foreign-born and growth among the native-born, where native-born growth was responsible for overall growth: 35 places

- Rural places with declines in both foreign-born and native-born residents that resulted in overall population decline: 407 places

- Rural places that saw growth among foreign-born residents and decline in native-born residents, where immigrant growth prevented larger loss, but the total nonetheless shrank: 1,475 places

- Rural places that saw foreign-born population decline and native-born population growth but declined overall: 12 places

Study findings

On the whole, these 2,767 places experienced a 4 percent decline in their adult population between 1990 and the end of the study. The native-born adult population shrank by 12 percent, while the foreign-born adult population grew by 130 percent.

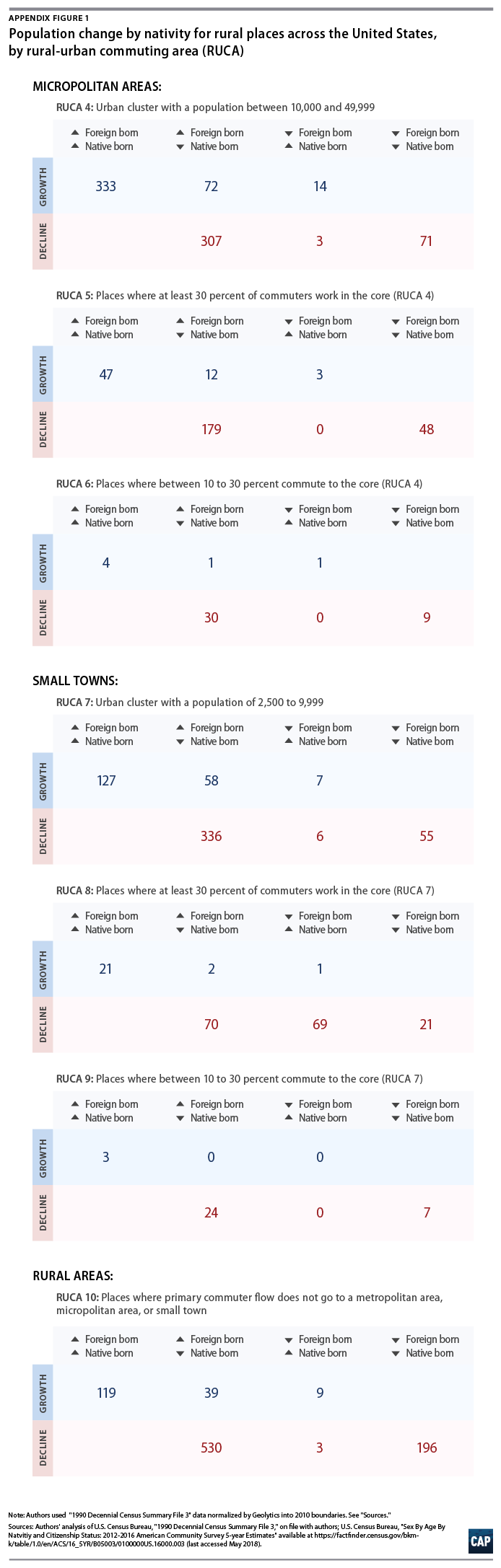

More than two-thirds, or 1,894, of the 2,767 places saw their population decline from 1990 to 2012–2016. Over this period, the most rural places were also the most likely to experience population decline. Overall, 57 percent of places characterized as micropolitan (RUCAs 4–6), 70 percent of small towns (RUCAs 7–9), and 81 percent of completely rural places (RUCA 10) saw their population fall. Given the literature on economic opportunities and demographic trends33, coupled with the overall decrease in the number of places that are considered completely rural, it makes sense that the most dramatic population declines occurred in places that were the most rural.

However, looking only at the overall population change masks important factors. In the vast majority of these places (1,475 of 1,894), despite an overall contracting of the population, the foreign-born population grew. In these 1,475 places, the foreign-born adult population grew by 157 percent, while their native-born adult population shrank by 31 percent. Without immigrants, the populations in these places would have contracted by 30 percent, even more staggering than the 24 percent they actually experienced. The trend registers across places that fall into each of the seven rural categories; between 73 percent and 85 percent of places saw their population decline partially offset by growth in foreign-born adult residents. The movement of foreign-born adult residents to a community means more taxpayers contributing to schools and roads; a larger customer base to attract grocery and retail stores, keep hospitals open and in business, and make it worthwhile for utility investment and advancement such as broadband; and a growing community to support civic organization and events enriching the local social fabric.

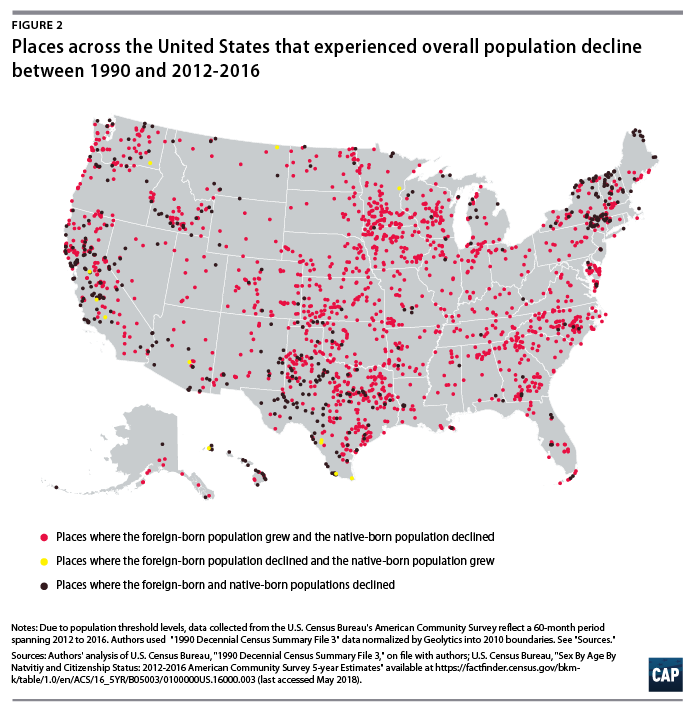

It is no surprise, given how many rural places experienced population decline, that these communities are fairly evenly distributed throughout the United States. However, places that saw declines in both their native-born and foreign-born adult populations are particularly noticeable in northeastern states such as Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, and New York; in western states such as Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and California; and in Arizona, Texas, and Michigan.

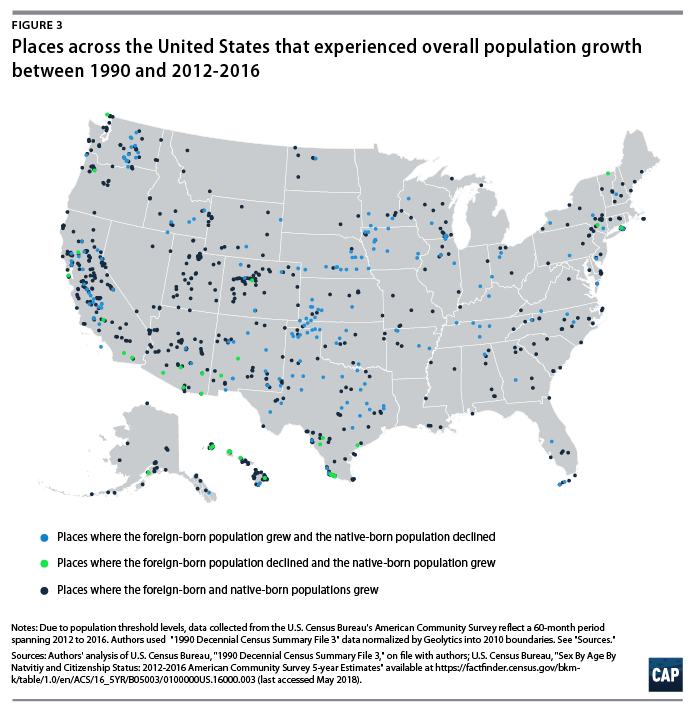

More than twice as many places’ populations declined from 1990 to 2012–2016 than grew. But three-quarters of the 654 places that did experience population growth in this analysis saw growth in both their native-born and foreign-born populations. In an additional 184 places—21 percent, or 1 in 5, of the 873 places that saw overall growth—immigrants played a vital role in this growth by completely offsetting the decline in the native-born population. This was particularly true with respect to places in certain RUCA codes—namely very rural areas (RUCA 10) and small-town cores (RUCA 7), at 23 percent and 30 percent, respectively.

Figure 3 shows the geographic distribution of the places that grew. They are mostly scattered through the West and Midwest, with clusters in eastern Washington and inland California; the stretch of Iowa, Nebraska, and Kansas; and in Oklahoma and Texas.

What happens when rural communities lose population?

In rural places where population loss is left unchecked, out-migration has harsh effects on people and the places they leave behind. Communities facing shrinking populations find that access to essential services, from schools to health care to grocery stores, suffers because it sometimes becomes too expensive to keep these services open. The closures of essential services can further push communities toward an existential threat as more people leave.34

School consolidations and school closures

A decreasing resident population translates to a falling school enrollment and a rising cost to educate each individual student. School districts often struggle to keep their doors open and opt to consolidate facilities in order to keep teachers’ jobs and maintain the quality of education.35 The closing of a local school, however, might be devastating for rural communities not only because these communities fail to attract young families, but because they also lose a center of a community.36 In 2014, Monticello, Maine, was forced to close Wellington Elementary School, a high-performing elementary school, after six decades of service to save money. Before it closed, Wellington was a hub for the small community, organizing a range of activities such as movie nights, picnics, and plays. With the school shuttered, students now bus an additional 14 miles each day to school, and residents worry that Monticello will turn into a “ghost town.”37

Some rural communities have reversed the impacts of population decline by attracting new residents to settle and work in their localities. In the late 1980s, Schuyler, Nebraska, and its long-time employer—a Cargill beef processing plant—successfully attracted many immigrant workers, mostly Latinos, to move there.38 By 2016, of Schuyler’s 6,100 total residents, almost 72 percent were Latino.39 During this same time period, the elementary school in Schuyler grew to become the second-largest school in Nebraska, and the high school is adding classrooms to meet the demand. Unlike many rural communities, Schuyler is thriving thanks in no small measure to a main street lined with Latino-owned businesses, from ice cream parlors to small shops and businesses. One of those businesses, a Latino-owned grocery store, attracts patrons from nearby cities such as Columbus, Norfolk, and Lincoln, Nebraska, because it sells specialty goods not found easily in other cities and towns.40

A cutback on health care services and hospital closures

Hospitals, like schools, anchor rural communities and provide health care services and good jobs to residents. Even without population decline, rural communities often lack sufficient access to high-quality and essential health care services because care facilities are often located far away from these communities. If a rural community is fortunate enough to have a hospital, these health care facilities generally experience a shortage of specialists and workforce.41 A declining and aging population exacerbates this problem, since low patient volumes increase the cost per patient and make hospitals financially unviable.42 Maternity wards are the first to go when hospitals pull back their services.43 Many women in rural counties find themselves traveling greater distances to receive basic prenatal care from an OB-GYN or to deliver their babies. For example, Winfield, Alabama—a city of less than 5,000 people —has a hospital that does not provide obstetrical services. As a result, women from Winfield must travel nearly 60 miles to Tuscaloosa, Alabama, to access these services.44

The lack of adequate health care is common in rural communities. According to the data collected by North Carolina Rural Health Research Program, 87 rural hospitals have closed nationwide since January 2010, and many more hospitals are at risk of closing.45 Approximately 41 percent of rural hospitals are operating at a negative operating profit margin—meaning their costs are greater than their revenues.46

Grocery store closures

There are a multitude of reasons why grocery stores shutter in rural communities, but primary among them is that the number of consumers able to sustain a local store is in decline.47 Other reasons include competing big-box chain stores, changing purchasing patterns, and aging ownership. Grocery store closures directly contribute to the growing number of areas with limited food-purchasing options, also known food deserts.48 Analysis shows that the largest concentration of counties designated as food deserts is in the Great Plains region, and among the 418 designated food desert counties, almost half are rural.49 The implications of losing a grocery store are huge on a community’s residents, many of whom are aging and lack reliable transportation. Furthermore, few families want to move to or stay in a place where there is limited access to healthy food. These factors will likely stunt a community’s population growth and further exacerbate economic decline.

Some rural communities have used creative methods to keep their grocery stores open, for example, by pooling their funds and investing in a store.50 In Walsh, Colorado, townspeople bought their closed-down grocery store, revamped it, and reopened it. Now the store is thriving.51 In other small communities, immigrants who have moved there to work in the fields and factories, from meatpacking to dairies, have provided a welcome relief and put a halt to empty storefronts.

Arcola, Illinois, a prosperous community in the midwestern portion of the state with a unique immigration history, is an example of how immigrants have played an outsized role to advance and keep a community alive. In the 1800s through the 1950s, Arcola was famous for its broomcorn—corn that is made into brooms.52 As the broomcorn industry transitioned, and Arcola’s farmers could not compete with cheaper products from abroad, the city started importing broomcorn from other countries. Some of the imported broomcorn came from Cadereyta Jiménez in Mexico, which was also famous for growing broomcorn. Along with the imported broomcorn, Mexican families already knowledgeable about growing and preparing broomcorn in Cadereyta Jiménez started moving to Arcola in search of better pay and opportunity.

During this same time frame, in 1957, as both the broomcorn industry and Arcola’s ethnic makeup were changing, Robert Libman, who also comes from an immigrant family, moved his family’s broom business to Arcola.53 Many immigrants who came from Cadereyta Jiménez found work in the Libman factory. Not surprisingly, Arcola’s prosperity and job opportunities attracted other immigrants as well. In 1990, Arcola had a total population of 2,678, among whom about 243, or 9 percent, were Hispanic.54 According to the 2012–2016 ACS estimates, the community’s population increased to 2,881, among whom 984, or 34 percent, were Hispanic.55

Tim Flavin, who heads the Mi Raza community center in Arcola, lives in a neighboring town that is suffering from people leaving town. He said that unlike Arcola, nearly all the businesses—“a grocery store, a restaurant, a gas station, a hardware store, and a library ”—where he lives have closed.56 He attributes Arcola’s prosperity and vitality to its immigrant population, which primarily works in the two broom factories and a cap-and-gown plant. He notes that besides working in those factories, “immigrants have also opened grocery stores, restaurants and a mechanic shop that employs 10 people. Some residents from India own two restaurants, two hotels and a gas station.”57

Immigrants are leaving an indelible mark on rural America

Immigrants, besides offsetting population decline in many rural communities, are a vital part of the rural economy and to communities’ social fabric. Immigrants are often integral to the redevelopment and revitalization of entire communities as they go about building lives in their new homes.

Immigrants contribute to building rural economies and communities

In rural communities, immigrants and refugees, who are often resettled there, do jobs that are essential for the survival of a number of key industries. While immigrants in rural communities are typically associated with agriculture, the rural United States is not a monolith, and immigrants own their own businesses and work in food processing, manufacturing, and tourism. Importantly, even in the agriculture industry, some immigrants have transitioned from seasonal workers to fill year-round positions that allow them to put down permanent roots in a community.58 In the end, immigrants make communities more stable and resilient to the changes plaguing rural communities such as an aging population and out-migration.

Meat processing plants in rural communities rely on immigrant workers

Large-scale meat processing plants have become anchor institutions in numerous rural communities, providing employment and bringing in new residents that result in population increases. As meat processing plants typically have low-paying jobs and high rates of injury and turnover, they have trouble attracting a sufficient number of U.S.-born workers and frequently rely on immigrants and refugees to fulfill their labor demands.59 Research has found that meat processing plants in rural areas bring significant changes to communities’ demographics and schools—mainly increasing population size, ethnic diversity, and school enrollment.60

Worthington, a rural community in Minnesota, has benefitted from the presence of a meat processing plant and the immigrant families it attracted.61 During the late 1980s, Worthington was reeling from a farm crisis and experiencing population decline, but the influx of immigrants in pursuit of jobs in the town’s pork plant revived the community and its downtown.62 New businesses opened, and struggling businesses saw their bottom lines grow. For example, former Mayor Alan Oberloh (D), also a car mechanic, began servicing more Hispanic clients.63 The percentage students of color at Worthington Public Schools increased to 67 percent in the 2017-2018 school year, up from 38 percent 15 years ago.64 Latinos made up about 49 percent of the total student population, and the schools adapted to serve the growing population by hiring 30 English language teachers and three full-time Spanish interpreters.65

Immigration can breathe fresh life into declining rural communities by reversing population loss, spurring economic growth, meeting labor needs to preserve key industries, contributing to the local tax base, and supporting hospitals and clinics to prevent health care deserts.

The story of how new immigrant workers are received in rural communities is not always positive, however. About 30 miles away from Schuyler, a meatpacking community that not only managed demographic changes but prospered because of them, the rural community of Fremont, Nebraska, tried hard to prevent the opening of a large Costco chicken plant. A news article reported that the strong opposition to opening the chicken plant in the city included an unlikely bunch: “aging nativists, good-government advocates, environmentalists, and advocates for workers’ rights.”66 Along with other concerns, opponents often explicitly stated that they did not want more immigrants and refugees in their community.67 Fremont was no stranger to demographic change: The community underwent a shift in the 1980s when its Hormel meatpacking plant replaced long-time workers’ well-paying, middle-class jobs with lower-wage positions. Tensions flared as many Latinos filled those jobs, and the community’s Hispanic population swelled from 165 residents in 1990 to nearly 4,000 in 2012–2016.68 In 2013, anti-immigrant sentiment was so pervasive that Fremont passed a housing ordinance prohibiting residents from renting to unauthorized immigrants.69

On the other side of the fight, residents who supported the Costco plant’s opening argued that in order to survive, Fremont needed the type of economic boost the plant could bring. Bob Missel, the chairman of Dodge County commission, pointed out that the plant would increase demands for soybean meal and corn, provide work for poultry farmers to operate more than 500 new barns throughout northeastern Nebraska, and bring nearly 1,000 jobs to Fremont. Costco moved forward with its plans, and as of June 2018, it broke ground in Fremont for a live animal processing plant, a first for the company.70 It remains to be seen how the community will react to potential new residents who may be drawn to Fremont to pursue job opportunities at the new Costco plant.

Even amid challenges, immigrants working in meat processing plants have revitalized rural communities

In 2008, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) conducted in Postville, Iowa, one of its largest worksite raids, where agents swept up nearly 400 unauthorized workers at Agriprocessors, a meat processing plant.71 Around 1,000 agents in helicopters and vehicles carried out the raid in the community, which had an estimated 2,300 residents. In the aftermath of the raid, many children were too scared to return to school and some stopped going altogether, and many family members who were left behind either followed those deported, mostly back to Guatemala, or moved away from Postville in fear of other enforcement actions. According to news reports, anywhere from one-third to half of Postville’s population left, bringing its population down to around 1,800 people.72 A string of misfortunes followed: Small businesses closed, and apartments and houses were left vacant. Research in Postville showed that families of deported workers suffered from long-term income loss even nine months after the raid and had to rely on charity and other types of support for survival.73

Agriprocessors attempted to stay afloat and tried creative ways to hire more workers. The New York Times reported that following the raid, the plant brought in 170 workers who traveled 8,000 miles from the Micronesian island of Palau, recruited Somali refugees from Minnesota, and transported homeless people from Texas to work.74 Not long after the raid, however, Agriprocessors’s executives and managers were charged with financial and immigration fraud, and the plant closed its doors, leaving behind unpaid taxes to the city.

In the nearly 10 years since the plant closed, a lot has changed in Postville. Agri Star, a new plant, has opened in the place of Agriprocessors, attracting new immigrant workers and refugees.75 The community is now facing challenges related to successfully embracing a new and diverse population of immigrants and their children. For example, cultural competency training is needed for teachers to better understand their Somali students, who may be misunderstood because they avoid eye contact as a sign of respect.76 Despite the challenges, these new populations have revived the community as new shops open and school enrollment increases. Although Postville had a small student body of about 750 students in 2016, 40 percent of its students spoke a language other than English, and students overall spoke about 14 different languages.77

Tzvi Bass, owner of a new Postville grocery store, remarked, “It was easy to destroy this town … it’s harder to rebuild. But I see it slowly, slowly coming back.”78

Recently, however, fears have spiked in Postville as President Trump takes harsher immigration enforcement actions. Somali immigrants have grown worried about the Trump administration’s executive order banning Somalis from entering the United States as immigrants79 and wonder what it will mean for them and their families. Still, Somalis and other immigrants remain cautiously hopeful and continue find Postville warm and welcoming.80

Immigrants have been an indispensable part of the agricultural sector

Over the decades, the rural economy’s dependence on the agricultural sector has slowly declined against a backdrop of growing service industries such as education and health care.81 Traditional sectors such as agriculture, forestry, fishing, and mining, however, remain vital for rural communities and provide employment to 1 out of every 10 rural workers.82 Family members, rather than hired workers, traditionally performed more farm work.83 With increased mechanization for some crops and higher productivity among agricultural industries, the demand for farm workforce decreased overall in the long term. As the number of family members involved in the farm also shrank over time, as indicated by data from 1950 to 2000, the reliance on hired farmworkers to fill many of these jobs increased.84 Research shows that it is difficult to hire U.S.-born workers to fill farm jobs because it is grueling work and does not pay well compared with jobs requiring similar skills, resulting in farm owners generally turning to immigrants in search of job opportunities to fill those hard-to-hire positions.85

An analysis of data collected in 2011 by the North Carolina Growers Association on the recruitment of U.S.-born farmworkers found that only 268 U.S.-born workers applied for nearly 6,500 available jobs, even though there were nearly 500,000 North Carolinians unemployed during that time.86 Among those U.S.-born workers hired, only seven of them, or 3 percent, completed the growing season compared with about 90 percent of the Mexican farmworkers.87 The dependence on immigrant labor is evident in crop production as well as on dairy farms. The U.S. Department of Labor’s National Agricultural Workers Survey (NAWS) found that among the hired crop workers surveyed, more than 70 percent were foreign-born, and a majority were from Mexico.88 Even among U.S.-born crop workers, 27 percent self-identified as Hispanic. A little more than half of those surveyed were unauthorized immigrants. Similarly, a 2014 survey of dairy farms found that half of their workers were immigrants, and dairies with immigrant labor produced nearly 80 percent of the total milk production in the United States.89

Kennett Square, Pennsylvania, is a rural community of about 6,000 residents with a thriving mushroom-farming community, which is part of the largest concentration of mushroom farms in southeastern Pennsylvania that contributes an estimated $2.7 billion to the local economy.90 The 2012–2016 ACS estimates show that the population is equally divided between Hispanics and non-Hispanic whites, and nearly 40 percent of the total population is foreign-born. Of those who are foreign-born, 90 percent are from Mexico. Kennett Square’s immigrants have taken part in its growth and have started a range of new businesses, from additional mushroom farms to hair salons, grocery stores, and restaurants and eateries.91 Similarly, farmers in rural Wisconsin, the second-highest milk-producing state, rely heavily on immigrants to work on their dairy farms because they are unable to find a sufficient number of U.S.-born workers. Wisconsin dairy farmers in places such as Mount Horeb and Dane report that finding U.S.-born workers to milk cows is difficult because work in dairy farms requires long hours and is strenuous.92 One of the dairy farmers who employs Hispanic immigrants stated, “We’ve run ads in the papers, looking for milking technicians or people to help milk cows and things like that. We don’t even get a bite. We don’t even get calls.”93

Under the Trump administration, farmers in both Pennsylvania and Wisconsin are running into issues due to contentious immigration rhetoric and enforcement actions that have had a chilling effect on foreign-born workers. Farmers say that the fraught political environment is hurting their businesses and report that they are “seeing labor shortages, and that threatens the vibrancy of our community.”94 One dairy farmer who voted for President Trump does not think that he understands the value of immigrant workers, regardless of their immigration status.95

Immigrant health care professionals provide vital care in rural communities

Recent academic reports have focused on the roles of immigrants in rural communities, and specifically on the contributions they make or can make in the health care industry. In general, rural areas suffer from widespread shortages of medical specialists, primary care physicians, and other health care professionals such as dentists and mental health care providers.96 These shortages are likely to worsen as communities find it harder to compete with metropolitan areas to attract and retain these workers.

In these circumstances, one way rural communities can counter the shortage of doctors is to incentivize foreign-trained doctors, or international medical graduates (IMGs), and foreign-born doctors to fill in the gaps in service through nonimmigrant visa opportunities. Foreign-born doctors who are green card holders or citizens are free to live and work wherever they choose. Other foreign-born doctors and IMGs, however, have mainly two nonimmigrant visa options to practice in the United States: Either they apply for a J-1 exchange visitor visa or they find an employer to sponsor them for an H-1B visa.97 Both of these options come with upsides and downsides.

Foreign-trained doctors play an outsized role in meeting the demands for basic medical care in rural communities, and immigrants are well-positioned to play an even bigger role in providing health care services, for instance as home health care aides.

Many IMGs are under J-1 exchange visitor visas that allow them to finish their medical residency training in the United States.98 After completing their degrees, however, IMGs are required to return to their home countries for two years before they are eligible to apply to return to the United States on an immigrant visa or certain nonimmigrant visas.99 In 2016, more than 10,000 foreign-trained physicians were approved for J-1 visas.100 One way doctors can avoid the two-year rule is to find an offer for full employment in a rural or an underserved area under the Conrad 30 Waiver program. Under the program, foreign-trained as well as foreign-born doctors can apply for an H-1B to serve for at least three years, after which they can apply for permanent U.S. residency.101 National data show that about 800 to 1,000 physicians per year use these waivers out of the available 1,500 slots.102 While there are statewide differences and flexibilities on where these doctors can practice, many of these waivered physicians provide much-needed care to rural populations.103

Other IMGs and foreign-born doctors also opt for an H-1B visa, a three-year nonimmigrant visa granted to skilled workers that can be renewed one time and does not come with a two-year condition like the J-1. Unlike the Conrad 30 Waiver, H-1B does not provide a direct path to permanent residency.104 Many foreign doctors who have H-1B visas also practice in rural and underserved areas even if they are not required to do so. For example, in Poplar Bluff, Missouri, Dr. Raghuveer Kura has served as a kidney specialist for nine years and has treated almost 3,000 patients.105 In a place where health care services are hard to access, his patients travel long distances for an appointment with him. Other rural communities around the United States also rely on foreign-born doctors for basic care. In Coudersport, Pennsylvania, for example, two Jordanian physicians play a key role in keeping the obstetrics unit of the local hospital open, and the hospital continues to recruit foreign specialists.106

Aside from doctors, the demand for home health aides—workers trained to take care of individuals’ immediate medical needs in their homes—is also likely to increase in rural places given that these communities’ populations are aging.107 Recent research from New American Economy, a coalition of business leaders and policymakers, shows that immigrant health aides could be uniquely positioned to relieve some pressure related to this demand given that, nationally, more immigrant health care workers are in health aide jobs compared with U.S.-born workers.108

Foreign-trained doctors play an outsized role in meeting the demands for basic medical care in rural communities, and immigrants are well-positioned to play an even bigger role in providing health care services, for instance as home health care aides.

Integration policies in rural areas

While immigrants can play an important role in revitalizing rural America, more needs to be done to welcome them into rural communities and provide opportunities for them to put down roots.

Rural areas experiencing substantial immigration for the first time can face greater challenges than historically diverse urban centers that have more experience integrating new immigrants. In more sparsely populated areas of the country, a demographic change can be abrupt and more acutely felt, leading to fears on the part of U.S.-born residents of cultural loss and erasure, job competition, and overextension of public resources.109 Immigrants arriving in rural areas must often contend with a lack of support from local government and nonprofit organizations, an absence of English as a second language (ESL) instruction in schools, and poor availability of critical bilingual services such as health and social service provision.110

Nevertheless, communities can take intentional actions to face these challenges and better facilitate the integration of immigrant populations. Community leaders need to build trust between immigrant and U.S.-born residents, help immigrant populations thrive, and inculcate all residents with a sense of community and shared values without effacing one culture or another.

Successfully implemented integration policies increases language-learning access, creates a shared vision of community values, and sets clear, compassionate enforcement practices.111 Early coalition-building among local stakeholders is key to establishing a framework for cooperation and a coherent strategy that can be revised over time as population needs change. Meanwhile, local political figures play a critical role in setting the tone of immigration discourse, which in turn can shape the U.S.-born population’s response and the types of laws and policies that are put into effect. Many of these strategies do not require significant resources, and any community can take advantage of them.

Success, failure, and something in-between

St. James, Minnesota, is a standout case of effective immigrant integration. In the 1970s and 1980s, St. James became a destination for immigrants when a local plant, Tony Downs Foods Co., began to recruit Hispanic workers and encourage immigrant families to relocate to the community of then fewer than 5,000 people.112 In response, St. James gathered a group of local stakeholders to form an organization called the Spirit of St. James to create a strategy for welcoming and including the immigrant population in the area.113 The coalition initially collected reflections from the U.S.-born population but focused later on immigrants, who described feeling watched in public spaces and being unable to navigate the resources available to them.114 In response to some of the issues raised during these discussions, St. James leaders formed another group comprised of school and social stakeholders called the Family Services Collaborative, which focused on making services accessible to immigrant families.115 The Family Services Collaborative worked to provide ESL programs in schools, translations of documents and informational pamphlets into Spanish, and initiatives specifically targeted to support transitory migrant families.116

Integration efforts in St. James have since evolved into several additional initiatives including the Horizons program, which provides integration training, and Unity-Unidad, which encourages positive relationships between U.S.-born and foreign-born residents.117 As a result, St. James has seen a marked decrease over time in intergroup hostilities, and its immigrant population has established itself, including new arrivals who are settling in the community.118

When local leaders fail to act appropriately, the consequences can be serious for rural communities. In the 2000s, for example, Hispanic immigration to Hazleton, Pennsylvania, increased rapidly as a proportion of the overall population, from 5 percent in 2000 to more than 37 percent in 2012.119 The large influx of immigrants reversed a seven-decade decline in population but produced a vocal, negative response from many longtime Hazleton residents. Instead of convening stakeholders to coordinate an integration strategy, local leaders inflamed the political climate by enacting the Illegal Immigration Relief Act of 2006, a local ordinance which levied a daily $1,000 fine against any landlord renting to an undocumented immigrant and imposed a five-year business license suspension on anyone who hired an undocumented worker.120 Then-Mayor of Hazelton Lou Barletta (R)—a current representative from Pennsylvania—spearheaded the act. It is also notable that Kansas Secretary of State Kris Kobach (R), then an out-of-town law professor, drafted the ordinance.121

The local legislative effort reinforced suspicion of all immigrants and was driven by false allegations that undocumented immigrants were driving up crime rates—a statistically false and damaging assertion.122 Local elected officials continued to point to anecdotal evidence of criminality to marshal political support for a hardline approach to enforcement.123

In 2015, a federal judge ruled against the law and ordered the city of Hazleton to pay $1.4 million in attorneys’ fees for the plaintiffs, an amount so large that officials had to take out a bank loan to make the payment.124 Even Mayor Joseph Yannuzzi (R), who took office after the controversy and was one of the proponents of the ordinance, admitted that immigration had revitalized parts of Hazleton’s economy and noted that school enrollments were high, vibrant shops replaced empty storefronts, and apartment complexes were filled with people.125

Many communities’ experiences fall somewhere in the middle of the welcoming attitude of St. James and the reactionary backlash of Hazleton. About 20 years ago in Beardstown, Illinois, a large local meatpacking plant attracted workers from a variety of backgrounds, including more than 900 immigrants from 34 countries.126 When foreign-born residents first started settling in Beardstown, racist graffiti often covered the lockers at the meatpacking plant, and Latino children faced harassment while travelling to and from school.127 ICE agents conducted several midnight raids on the meatpacking plant in 2007, leading to tension and fear in the community.128 However, attitudes changed over time as U.S.-born and foreign-born populations interacted, and immigrant residents opened small businesses and revitalized the community.129 The shift produced a series of integration efforts such as bilingual liaisons at schools for immigrant students, ESL and citizenship classes for employees of the meatpacking plant, multilingual church services, and cultural celebrations in the town square.130 Although a lack of community leadership initially delayed these efforts, social and economic integration in Beardstown are now in full swing, staving off the population and job loss of surrounding areas.131

Lessons for rural communities

The cases of St. James, Hazleton, and Beardstown demonstrate important takeaways for rural areas looking to integrate immigrant populations. Immigrants can play a large role in stemming the effects of population decline in rural America. However, the positive impacts of having newcomers settle in these places could be even greater if communities are deliberate in developing and implementing plans to bring residents from different backgrounds together and help immigrants integrate into their new homes by providing critical services to guide their adjustment. This is crucial in communities where services are often scarce. Rural communities should develop plans that recognize the following realities.

- Immigrant integration policies in the United States are localized, leading to divergent approaches and outcomes across communities.132 This is both a challenge and an opportunity for jurisdictions receiving immigrant populations. On the one hand, state and local governments have some primacy and autonomy in designing bottom-up solutions that are appropriate to specific environments. On the other hand, communities experiencing large-scale immigration for the first time can be left in the lurch, without guidelines and assets in place to address changing needs. In St. James, community leaders took advantage of their discretion to plan proactively, organizing a new framework for intergroup interaction and social service provision that could address both immediate imperatives and evolving needs over time. These actions decreased hostility and increased the social and economic participation of immigrant populations to the whole community’s benefit. In contrast, neither Hazleton nor Beardstown sought to create proactive solutions to the demographic shock of increased immigration. Instead, the Hazleton city council passed a reactive ordinance drafted by an outsider that inflamed the community, while Beardstown failed to manage an initial backlash that harmed immigrant families. Rural communities facing similar challenges today can learn from these and other communities that experienced flows of immigrants on how to best manage—and potentially embrace—change in a way that benefits the entire community.

- Communities that want to welcome immigrants, increase integration, and harness the benefits should take conscious steps to facilitate civil discussions that involve everyone in their communities. In St. James, local politicians purposefully used welcoming language and the Spirit of St. James talks that drew from both immigrant and nonimmigrant perspectives in order to assess needs before proceeding with service provision and community-building networks. In Beardstown, employees at the meatpacking plant are represented by the United Food and Commercial Workers Union, which has several immigrant representatives voicing their communities’ concerns. Moreover, Beardstown’s former Mayor Bob Walters recognized the contributions of foreign-born residents, noting that immigrant families routinely purchase and restore run-down houses.133 Even in Hazleton, Mayor Yanuzzi spoke of decreasing long-term intergroup hostilities as young people intermingled, but it has proven difficult to counteract the harmful antics of the former mayor, who once arrived at a city council meeting in a bulletproof vest and “had long maintained that ‘illegal’ immigrants had flooded the town and driven up crime rates.”134 While there may be short-term political advantages for elected officials to incite and capitalize on fears, communities suffer in the long term. Local leaders in rural areas must take care to set an inclusive political tone and provide representation to both U.S.-born and foreign-born populations.

- The most critical services for immigrant families often revolve around language learning, educational access, and social inclusion. Beardstown takes care to offer resources for learning English and provides multilingual liaisons in schools in order to support immigrant students, reach across language barriers, and involve families in their children’s education.135 Beardstown also facilitates intergroup relations and cultural education of U.S.-born residents with initiatives such as Cinco de Mayo celebrations in the town square.136 St. James works to provide ESL classes in schools through the Family Services Collaborative and to create relationships between U.S.-born and foreign-born residents through Unity-Unidad.137 Still, other opportunities exist to further improve integration through community and local government initiatives. For example, a program evaluation study of an occupational Spanish program that the Vermont Agency of Agriculture piloted between 2007 and 2010 found that dairy farmers with a mostly Hispanic workforce improved communication between management and workers.138 In addition, although many integration efforts have evolved in rural communities to introduce immigrants to American culture, there are fewer organized efforts to expose U.S.-born populations to immigrant cultures, resulting in a largely one-sided exchange that veers uncomfortably close to assimilation or the effacement of foreign values and customs.139 Educational programs targeted at U.S.-born individuals could facilitate harmonious cultural exchanges in a more two-way process.

Conclusion

Immigration can breathe fresh life into declining rural communities by reversing population loss, spurring economic growth, meeting labor needs to preserve key industries, contributing to the local tax base, and supporting hospitals and clinics to prevent health care deserts. Fostering the potential benefits of these new residents is far from a given, however, and communities would do well to take intentional and proactive steps toward integration.

Local leaders and stakeholders must use an organized and thoughtful approach to lift up and reconcile both U.S.-born and foreign-born voices in a responsible and inclusive political and social climate. Local needs must guide the development of a set of tools and organizations to address the concerns of communities both in the present and over time, including programs for English instruction, bilingual services for immigrant families, and initiatives geared toward intergroup social interaction.

While the story of communities such as St. James speaks to the value of acting early, the examples of Beardstown and Postville illustrate that even communities that have suffered from division and tension can heal and move forward with a modicum of strategic planning and some good-faith effort. Hazleton is already looking toward a brighter future, and other rural communities around the country can follow suit, reaping rewards by welcoming immigrant families as neighbors. Small communities such as Fremont, where the Costco chicken plant is set to open, can get ahead of the curve by openly embracing the change that is coming, including the economic growth that the new workers and their families will create.

Admittedly, population increases and demographic changes can pose challenges, for example, by requiring communities to meet a higher demand for goods and services and accommodate the needs of a different population such as English language learners at school. But finding solutions to meet these demands and counteract challenges may be considered an investment in—not a cost to—the future growth and sustenance of a rural community. Future research should go deeper into understanding the ways immigrants can fit into rural life and the mechanisms in which policymakers, residents, and immigrants can work together to make a prosperous community.

About the authors

Silva Mathema is a senior policy analyst for Immigration Policy at American Progress. Previously, she worked as a research associate for the Poverty and Race Research Action Council, where she studied the intersections between race and ethnicity issues and policies regarding affordable housing and education. She earned her Ph.D. in public policy from the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, where her dissertation focused on the impact of a federal immigration enforcement program on the integration of Hispanic immigrants in Charlotte-Mecklenburg, North Carolina, and a Bachelor of Arts in economics from Salem College. She is originally from Kathmandu, Nepal.

Nicole Prchal Svajlenka is a senior policy analyst for Immigration Policy at American Progress. Prior to joining American Progress, Svajlenka worked at the Pew Charitable Trusts, where she examined the relationships between federal, state, and local immigration policies. Before Pew, Svajlenka worked at the Brookings Institution, where she conducted quantitative research on immigration, demographics, human capital, and labor markets in metropolitan areas across the United States. A Chicagoland native, Svajlenka holds a Master of Arts in geography from George Washington University and a Bachelor of Arts in environmental geography from Colgate University.

Anneliese Hermann is a former intern for Immigration Policy at American Progress. She holds a master’s degree in public administration from the University of Georgia.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Tom Jawetz and Philip E. Wolgin of the Center for American Progress for their invaluable input and support throughout the project. The authors are also grateful to Binh X. Ngo, a former intern for Immigration Policy at the Center, for her help with research and fact-checking.

Methodological appendix

Data sources

This analysis is based on population change from 1990 to 2012–2016, using the Decennial Census and the American Community Survey (ACS). Data from the 2012–2016 ACS are available via the U.S. Census Bureau’s American FactFinder.140 Because geographies change over time, 1990 data was purchased from Geolytics, which standardized 1990 data into 2010 Census delineations.141

Establishing rurality

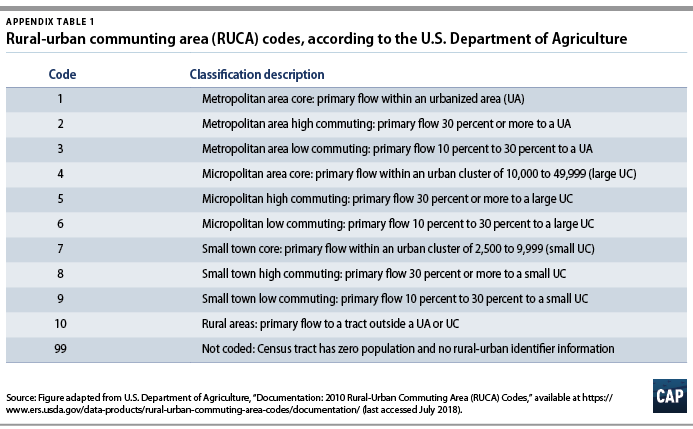

This analysis uses the USDA’s RUCA codes, which are assigned to every census tract in the United States.142 The codes are a 10-tier classification of census tracts. Tracts are assigned a RUCA from 1 to 10 based on “measures of population density, urbanization, and daily commuting to identify urban cores and adjacent territory that is economically integrated with those cores,” and reflects the OMB’s metropolitan and micropolitan areas.143 Three RUCA codes are for metropolitan areas and their influence shed, three are for micropolitan, three are for small-town tracts, and one is for rural areas. These help the authors identify a more granular level of rural and urban that is present below the county level. This analysis considers RUCA codes 4 and higher to be rural.

The following table, taken directly from the USDA website, describes each classification code.

Determining place-to-tract relationship

The Missouri Census Data Center’s MABLE/Geocorr14: Geographic Correspondence Engine gives users the ability to identify how different geographic levels intersect one another. In this report, they were used to show the relationships between all census tracts and places.144 Each census tract was assigned to a place (or in some cases, not a place) based on the share of tract population that lived in that place. Most places consist of more than one census tract.

Each place was assigned one RUCA code regardless of how many tracts of differing codes were in the place. Overall, 25,779 places were made up of tracts with the same RUCA codes, and 3,496 places were made up of tracts with multiple RUCA codes. If a place was made up of tracts with multiple RUCA codes, the authors determined which RUCA tract type the majority of residents lived in and assigned the place that code. For example, if 95 percent of residents of a place live in tracts that have a RUCA of 1, and the other 5 percent live in tracts that have a RUCA of 2, the place is assigned a RUCA of 1.

Most places that contain tracts with multiple RUCAs are similar to this example, where most residents in one RUCA classification and only a small percent live in some other RUCA classification. However, that is not always the case. The analysis included three flags to ensure that places that cannot be neatly categorized into a RUCA are excluded. Flags were applied to any place where less than 60 percent of residents lived in the primary RUCA classification.

- Flag 1: If the primary RUCA assignment and the second RUCA assignment are three or more classifications apart from one another, it was flagged for exclusion.

- Flag 2: If a place was made up of more than two types of RUCAs, it was flagged for exclusion.

- Flag 3: If less than 55 percent of the total population lived in the primary RUCA, it was flagged for exclusion.

Of the 3,496 places where less than 60 percent of residents lived in tracts assigned the primary RUCA code, 214 were removed because of the aforementioned flags.

Population change

Similar to other methodologies examining foreign-born contributions to population growth, this analysis examined population change by nativity for residents who are 18 and older.145 Children of immigrants born in the United States are native-born and would be included in the count of native-born residents. Those born after 1990, however, would show up in a growing native-born cohort in 2012–2016, despite being part of immigrant families and likely being considered part of the immigrant community. This could inflate the native-born growth by including children born to immigrants, and excluding those under 18 produces a more conservative estimate of change. All references to population change reflect the population that is aged 18 and older.

Population change components were calculated for places that met the following criteria:

- Rurality: The place was assigned a RUCA classification of 4 or higher.

- Size of foreign-born population: The place had foreign-born adult residents in 1990, and at least 5 percent of the adult population was foreign-born from 2012 to 2016.

- Total size: The place’s total population was at least 100 residents of all ages in both 1990 and from 2012 to 2016.

- Flags: The place did not receive any of the three flags discussed previously.

Of the more than 29,000 places in the United States recognized by the U.S. Census Bureau, 2,767 were categorized based the criteria above.146 Unlike the 2012–2016 ACS 5-year estimates, 1990 data from Geolytics do not include margins of error, meaning the authors cannot determine if a change is statistically significant or not. Setting up a wide swath of parameters and flags helps to ensure the authors are only making comparisons that would be more likely to pass such tests and is an attempt to safeguard against places that have seen very large changes relative to very small starting bases.

Typology

Each place was assigned 1 of the following 6 typologies based on the components of their population change:

- Places with increases in both foreign-born and native-born residents, thus resulting in overall population growth.

- Places that saw growth among their foreign-born population and a decline or no change in their native-born population, but with immigrant growth large enough to completely offset the decline, resulting in overall growth.

- Places that saw a decline or no change among their foreign-born population and growth among their native-born population, and where native-born growth was responsible for overall growth.

- Places with a decline or no change in both foreign-born and native-born populations, coinciding with an overall population decline.

- Places that saw growth among their foreign-born population and a decline or no change in native-born population, where immigrant growth prevented larger loss, but the total population still shrank.

- Places that saw their foreign-born population decline or remain the same and native-born population grow, but where population declined overall.

Figure 1 displays the overall results, and Appendix Figure 1 parses out this information based on RUCA classifications.