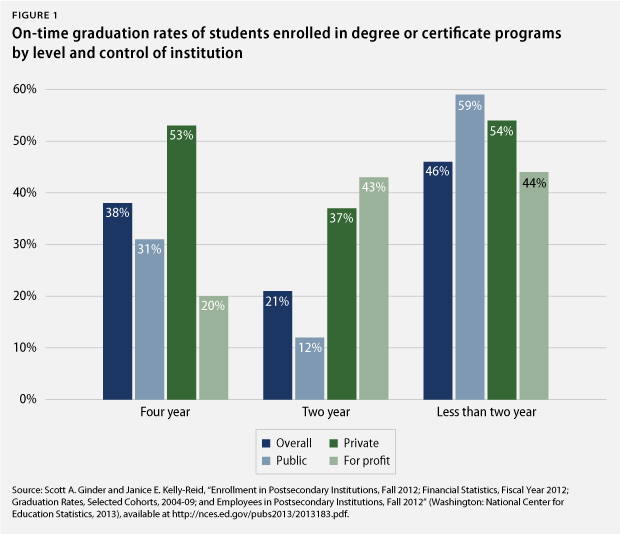

Students and families paid more than $154 billion in tuition and fees to attend public, private, and for-profit colleges, universities, and trade and technical schools in the 2011-12 academic year, borrowing more than $106 billion to attend those institutions under the William D. Ford Federal Direct Loan Program. When writing those checks and taking out those loans, few people realize that only 38 percent of students who enter a four-year degree program and 21 percent of students who enter a two-year degree program graduate on time.

To address these issues, President Barack Obama launched the College Scorecard in February 2013. This tool helps prospective students and their families quickly compare institutions of higher education on four key elements: cost, graduation rate, median amount borrowed, and loan default rate. More recently, he called on the U.S. Department of Education to create a college rating system that identifies institutions that provide the best value for students and families. Consumers could use this rating system as early as the 2015-16 academic year to compare schools with similar missions.

The system would also help identify colleges that do the most to help students from disadvantaged backgrounds, as well as institutions that are improving their performance on this measure. In announcing the rating system, the president stressed that students could continue to choose the college or university they want to attend but offered the possibility that taxpayers might be more generous to students attending high-performing colleges. To tie financial aid to performance, Congress would need to amend the Higher Education Act, or HEA, of 1965 upon its next reauthorization to allow consideration of the college rating system in the awarding of aid. While the creation of a rating system could be accomplished without changes to HEA, using those ratings to change how federal student-aid funds are awarded would require a change to the law.

The federal government’s plan

Since the president’s announcement, the Department of Education has been holding public hearings around the country to gather input from students and their parents, state leaders, college presidents, and others on how to develop a rating system that puts a fundamental premium on measuring value while ensuring college access for those with economic or other disadvantages. Inside Higher Ed recently obtained the written comments received by the Department of Education and made them publicly available. Not surprisingly, college and university faculty and administrators have expressed concern that the rating system will include graduates’ earnings, which raises the prospect that higher-education institutions will be judged, in significant part, by the earnings of recent graduates.

These critics argue that the true value of higher education comes not from the amount that people are paid but from the significance and meaning of the work that students do for the nation, their communities, or their employers. So judging institutions based in whole or in part on earnings, they argue, would penalize colleges whose graduates go on to do important but low-paying jobs, such as social work or teaching. Overall, the comments received by the Department of Education are consistent with last year’s Gallup/Inside Higher Ed poll, which found that most college presidents are skeptical that the rating system will effectively reduce the cost of college. But a change to the quality-assurance system in higher education—whether in the form of ratings or another system—is critically needed and should focus on access, affordability, retention and completion, and post-graduation labor-market outcomes.

With that said, the value of higher education cannot be reduced to a single value, such as the median or average earnings of graduates. As Secretary of Education Arne Duncan has indicated, an assessment of the value of a higher-education institution must include the consideration of a number of factors, including:

- Access: percentage of students receiving Pell Grants

- Affordability: average tuition, scholarships, and loan debt

- Outcomes: graduation and transfer rates, graduate earnings, and advanced degrees of college graduates

Ultimately, the Department of Education will need to refine the measurements used in an alternative quality-assurance system as additional data are developed and institutions work to improve their performance. But critically, aid must focus on providing students with Pell Grants and affordable loans so that they may attend high-performing colleges.

How schools are currently evaluated

Rating higher-education institutions is not new. Moody’s Investor Services rates colleges and universities to assess credit risk in order to help investors, colleges and universities, and other interested parties understand the risks that the U.S. higher-education sector faces. Only a small fraction of all institutions are captured in the Moody’s rating system because it is used for a specific purpose, but the notion of placing institutions in broad categories that reflect their performance against predetermined qualitative and quantitative measures is not new.

A number of media publications, including U.S. News & World Report, The Princeton Review, and Washington Monthly, produce rankings. Each of the ranking systems differs in scope and methodology. As the most well-known publication, U.S. News & World Report ranks 1,800 institutions of higher education and recently updated its methodology to reflect the current state of college admissions and better measure student outcomes. Washington Monthly includes 1,572 public, private nonprofit, and for-profit colleges and universities, while The Princeton Review only includes 378 institutions, which enroll less than 1 percent of all college students.

The current ranking systems, particularly the very popular U.S. News & World Report rankings, have changed institutions’ behavior in ways that often do not serve students well. For example, U.S. News & World Report’s use of rejection rates has caused institutions to try to drive up the number of people that apply simply so that schools can reject them. There have also been reports that institutions raise faculty salaries or reduce class sizes simply to move up in the rankings.

The federal government has a long history of providing information about colleges and universities to prospective students. Beginning in the late 1990s, the National Center for Education Statistics, or NCES, made certain Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System information available in a searchable online system called College Opportunities On-Line, or COOL. NCES’s current consumer information tool—College Navigator, which provides information about more than 7,500 institutions—replaced COOL in 2007. However, the federal government carefully avoided creating a rating or ranking system until Congress required the Department of Education to make public the rankings of colleges based on the highest and lowest academic-year charges and net price. Those rankings, along with the College Scorecard, are available at the College Affordability and Transparency Center.

A new rating system for colleges and universities

Because the weight of any federal action to create a new accountability system will inherently change behavior, it is critically important to consider how institutions will respond to mitigate any perverse effects. A federal accountability system should operate more like the Moody’s rating system than a ranking system, with institutions placed in large categories reflecting performance against key metrics. Among the key metrics that must be included in the accountability system are:

- Whether the institution provides access to underserved populations

- Whether the institution is affordable—after the consideration of federal, state, and institutional grants—to students from low- and middle-income families

- Whether the institution retains and graduates students from low- and middle-income families on time—two years for an associate’s degree and four years for a bachelor’s degree

- Whether graduates successfully go on to graduate school, professional education, or enter the workforce and earn an adequate amount to meet the needs of their families and comfortably repay their student loans, either through service or regular monthly payments

The accountability system should categorize institutions to reflect overall performance against all four measures, with a platinum rating identifying the top-performing schools. Students attending an institution in the platinum category would be eligible to receive additional unsubsidized student loans and more than one Pell Grant in an award year in order to encourage year-round attendance.

Institutions that perform strongly on three of four measures—access, affordability, retention and graduation, and the graduate school, professional school, and employment outcome—would be assigned a gold rating. Students attending institutions with a gold rating would be eligible to receive additional unsubsidized student loans but no additional Pell Grants.

Institutions with acceptable but not strong performance on the metrics would be assigned a silver rating, which would include the vast majority of institutions. Students attending institutions with a silver rating would not be eligible to receive additional unsubsidized student loans or Pell Grants.

Institutions with unacceptable performance on one or more of the metrics would be assigned either a bronze or lead rating. Institutions that provide access and are affordable would be assigned a bronze rating and would not be eligible to receive additional unsubsidized student loans or Pell Grants. As described in greater detail below, the Department of Education could require institutions with a bronze rating to buy bonds supporting a percentage of their students’ federal direct loans. Since these institutions provide access and affordability, the focus of federal policy should be to improve their performance on retention, graduation, and the graduate school, professional school, and employment outcomes.

Finally, institutions with poor performance on all measures or that provide access but are not affordable or do not have fair outcomes would be assigned a lead rating. These institutions would ultimately become ineligible to participate in federal student-aid programs if they do not improve. As with the bronze-rated institutions, they would be required to buy bonds supporting a percentage of their students’ federal direct loans until they become ineligible to participate in federal student-aid programs.

As conceived, the new accountability system could operate in conjunction with the requirements for institutional and program eligibility to participate in the federal student-aid programs. Currently, a state must authorize higher-education institutions to offer educational programs beyond high school, and an agency recognized by the federal secretary of education must accredit institutions.

Yet a new accountability system based on ratings could be used to establish eligibility to participate in federal programs. In this case, accreditation could be decoupled from the aid system and become a true community of practice. Such an approach, however, likely would require that some institutions have a stake in the process in order for their students to receive federal student loans. The rating system describes an approach that could require institutions to buy a special class of 10-year Treasury notes with yields equal to the most recent cohort’s default rate multiplied by prior-year loan volume. The base yield would be the same as regular 10-year Treasury notes, but institutions with better-than-expected graduation and repayment rates would receive a bonus, and institutions with poorer-than-expected graduation and repayment rates would receive a lower yield.

On January 24, the yield on 10-year Treasury notes was 2.75 percent. Under this proposal, an institution that had a graduation rate that was 10 percent better than expected might receive a yield of 3.025 percent on the notes that they were required to buy, while an institution that had a graduation rate that was 10 percent lower than expected might receive a yield of 2.475 percent.

Higher-education institutions with bronze ratings would be eligible to receive support from the federal government to improve performance from revenues generated by the additional lending under the federal direct loan program to students attending platinum and gold institutions. Like some institutions do today under HEA’s current Title III and Title V, the poor-performing institutions would be able to take steps to improve their performance in terms of student graduation and employment outcomes, potentially tied to commitments to meet certain agreed-upon performance expectations. This additional revenue would be put into performance-based funding tied to the agreed-upon outcomes.

The federal government has long supported programs under Titles III and V to help institutions that disproportionately serve low-income and minority students improve academic programs and administrative and fundraising capabilities. These programs have served historically black colleges and universities, tribal colleges and universities, Hispanic-serving institutions, predominantly black institutions, Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian-serving institutions, Native American-serving nontribal institutions, and Asian American and Pacific Islander-serving institutions. But this approach could also provide an alternative and sustainable funding stream that could be devoted specifically to improving the performance outcomes of poor-performing institutions that provide access and affordability to underserved groups.

Conclusion

A new accountability system for postsecondary education institutions that ensures the integrity of federal student-aid programs is long overdue. In the absence of such a system, many students will continue to enroll in institutions with poor outcomes and receive federal student aid to attend those schools. Those most at risk because of inadequate preparation, lack of family support, and other factors will still struggle to complete a degree program and find a job in a rewarding occupation. While a new accountability system will not guarantee every student’s success, it will improve the odds for our nation’s college students and ultimately begin to restore public confidence in the higher-education system by showcasing the best institutions and addressing the very real problem of students and taxpayers paying tens of thousands of dollars to attend institutions with poor outcomes.

David A. Bergeron is the Vice President for Postsecondary Education at the Center for American Progress.