Introduction and summary

The number of rural hospital closures in the United States has increased over the past decade.1 Since 2010, 113 rural hospitals,2 predominantly in Southern states, have closed. This is a concerning trend, since hospital closures reduce rural communities’ access to inpatient services and emergency care.3 In addition, hospitals that are at risk financially are more likely to serve rural communities with higher proportions of vulnerable populations.4

Understanding the financial pressures facing rural hospitals is imperative to ensuring that America’s 60 million rural residents have access to emergency care.5 Rural hospitals are generally less profitable than urban ones, and those with the lowest operating margins maintain fewer beds and have lower occupancy rates. Low-margin rural hospitals are also more likely to be in states that have not expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act (ACA). According to new analysis by the Center for American Progress, future hospital closures would reduce rural Americans’ proximity to emergency treatment. Among low-margin, rural hospitals—those most likely to close—the majority of those with emergency departments are at least 20 miles away from the next-closest emergency department.

This report first discusses the role that hospitals and emergency care play in rural health care as well as trends in hospital closures. It then uses federal data to examine differences in the financial viability of rural and urban hospitals and the availability of hospital-based emergency care in rural areas. The final section of this report offers policy recommendations to improve health care access and emergency care for rural residents.

Rural hospitals have been closing at an unprecedented rate

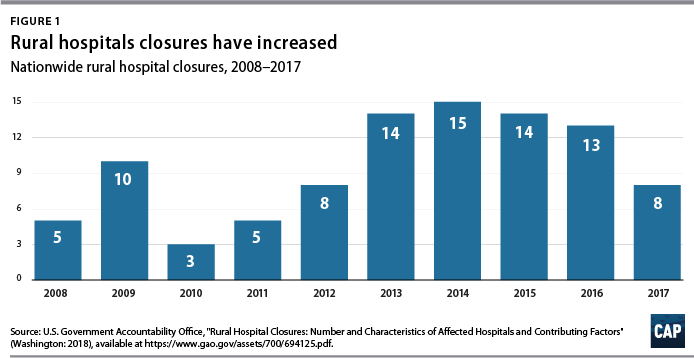

From 2013 to 2017, rural hospitals closed at a rate nearly double that of the previous five years.6 (See Figure 1) According to the Government Accountability Office (GAO), recent rural hospital closures have disproportionately occurred among for-profit and Southern hospitals. Southern states accounted for 77 percent of rural hospital closures over that time period but only 38 percent of all rural hospitals in 20137

Hospital closures may deepen existing disparities in access to emergency care. Closures are more likely to affect communities that are rural, low income, and home to more racial/ethnic minority residents.8 Although about half of acute care hospitals are located in rural communities and the other half are located in urban areas,9 rural residents live 10.5 miles from the nearest acute care hospital on average, compared with 4.4 miles for those in urban areas.10 According to a poll by the Pew Research Center, about one-quarter (23 percent) of rural residents said that “access to good doctors and hospitals” is a problem in their community, while only 18 percent of urban residents and 9 percent of suburban residents said it was a problem.11

A variety of factors influence hospitals’ sustainability. Thanks to medical and technological advances, conditions that once required hospitalization can now be treated in an ambulatory care center or a physician’s office. University of Pennsylvania professor and CAP nonresident senior fellow Ezekiel Emanuel has argued that one reason hospitals are closing is that “more complex care can safely and effectively be provided elsewhere, and that’s good news.”12 As a whole, the hospital industry remains highly profitable, and hospital margins are at their highest in decades.13

Evidence on the relationship between hospital closures and health outcomes is mixed. A 2015 study of nearly 200 hospital closures in Health Affairs found no significant changes in hospitalization rates or mortality in the affected communities, whether rural or urban.14 More recent studies have found an association between rural hospital closures and increased mortality. Harvard researcher Caitlin Carroll showed that rural hospital closures led to an overall increase in mortality rates for time-sensitive health conditions,15 and Kritee Gujral and Anirban Basu of the University of Washington found that rural hospital closures in California were followed by increases in mortality for inpatient stays.16

In rural areas, hospitals face additional challenges to their viability, including lower patient volumes; higher rates of uncompensated care; and physician shortages.17 In addition, rural patients tend to be older and lower income.18 Rural hospitals tend to be smaller, serve a higher share of Medicare patients, and have lower occupancy rates than urban hospitals.19 Rural hospitals commonly offer obstetrics, imaging and diagnostic services, emergency departments, as well as hospice and home care,20 but patients needing more complicated treatment are often referred to tertiary or specialized hospitals. In fact, rural patients are more likely to be transferred to another hospital than patients at urban hospitals.21

Most urban hospitals are reimbursed under the prospective payment systems (PPS) for Parts A and B of Medicare. Through both the inpatient and outpatient PPS, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) reimburse hospitals at a predetermined amount based on diagnoses, with adjustments—including those for local input costs and patient characteristics.22 However, rural hospitals often face higher costs due to lower occupancy rates and provide care to a higher percentage of patients covered by Medicare, Medicaid, and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). Such hospitals may be eligible to receive higher payments from Medicare if they qualify as a Sole Community Hospital (SCH) or Medicare-Dependent Hospital (MDH).23

Another form of financial relief for rural hospitals is obtaining designation as a Critical Access Hospital (CAH), which Medicare reimburses based on cost rather than on the PPS.24 To qualify as a CAH, a hospital must provide 24/7 emergency services; maintain no more than 25 beds; and serve a rural area that is 35 miles from another hospital.25 Medicare reimburses CAHs at 101 percent of reasonable costs, rather than through the inpatient and outpatient PPS structures.26 As of 2018, there were 1,380 CAHs nationwide,27 accounting for about two-thirds of all rural hospitals.28

Even with cost-based reimbursement, however, some CAHs are unable to sustain the costs required to maintain inpatient beds.29 The 25-bed limit for CAHs prevent participating hospitals from eliminating inpatient services and restrict their ability to expand in response to fluctuations in community populations or care volumes. Other challenges facing rural hospitals include lacking sufficient patient volume to maintain high-quality performance for certain procedures and pressure to drop high-value but poorly reimbursed services such as obstetrics while maintaining low-volume, high profit services such as joint replacement procedures. 30

A key way that states can support struggling rural hospitals is by expanding Medicaid under the ACA. Expanding Medicaid increases coverage among low-income adults, 31 which in turn reduces uncompensated care costs for hospitals32 and allows financially vulnerable hospitals to improve their viability.33 Consistent with other recent studies,34 the GAO concluded in a 2018 report on rural hospitals that those “located in states that increased Medicaid eligibility and enrollment experienced fewer closures.”35

Rural hospitals are cutting back on services

Rural hospitals in different states have responded to financial pressures in a variety of ways, trying to balance community needs with financial viability. For many hospitals this has meant cutting inpatient obstetric services, leaving more than half of rural counties without hospital obstetric services.36 For instance, in Wisconsin, falling birth rates led to 12 hospitals in the state closing their obstetric services in the past decade.37 In Grantsburg, Wisconsin, lower birth rates and an older community population led Burnett Medical Center to shut down its obstetrics services.38 In order to offer these services, Burnett Medical Center would have needed to keep a general surgeon on call to perform caesarean sections, and with just 40 deliveries in 2017, the hospital could not justify the expense.39 While the hospital will continue providing prenatal and postnatal care, it will refer patients to a facility in Minnesota for deliveries—a facility is almost 40 minutes away.40

In other communities, hospitals have been replaced by other types of health care facilities. For example, Appalachian Regional Healthcare System closed Blowing Rock Hospital in North Carolina in 2013. Three years later, it opened a 112-bed post-acute care center in Blowing Rock in response to demand for rehabilitation services and the aging population in the surrounding area.41

Financial data shows that rural hospitals are more likely to struggle

To compare the financial situations of rural and urban hospitals and examine how future rural hospital closures could affect the availability of emergency care, CAP analyzed data from the CMS Healthcare Cost Report Information System (HCRIS). The CMS requires all Medicare-certified hospitals to report their financial information annually. CAP used the HCRIS to examine the financial margins and other characteristics of 4,147 acute care hospitals for fiscal year 2017. Of these, 1,954 hospitals (47 percent) were in rural areas, while the remaining were in urban areas. Hospitals self-report their status in the HCRIS as either urban or rural, which the CMS defines as either inside or outside of a metropolitan statistical area, respectively.42 Further information about CAP’s hospital sample can be found in the Methodological appendix.

Hospital operating margins, which measure excess patient-related revenues relative to patient-related expenses, are often used as an indicator of financial health.43 A 2011 study by Harvard researchers Dan Ly, Ashish Jha, and Arnold Epstein found that the lowest 10 percent of hospitals by operating margin were 9.5 times more likely to close within two years compared to all others. 44 The same study concluded that hospitals with low operating margins were also more likely to be acquired or merge.45

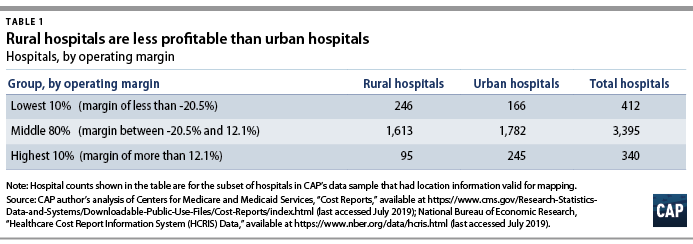

In CAP’s hospital sample, the median operating margin was negative 2.6 percent among all hospitals, negative 0.1 percent for urban hospitals, and negative 4.9 percent for rural hospitals.46 Public hospitals and MDHs in the sample were more likely to have negative operating margins, consistent with what other studies have found.47 To analyze hospitals’ relative financial health across geographic areas, CAP ranked hospitals in the HCRIS sample based on operating margin, splitting them into three groups: the lowest 10 percent, the middle 80 percent, and the highest 10 percent. The range of operating margins for each group is shown in Table 1.

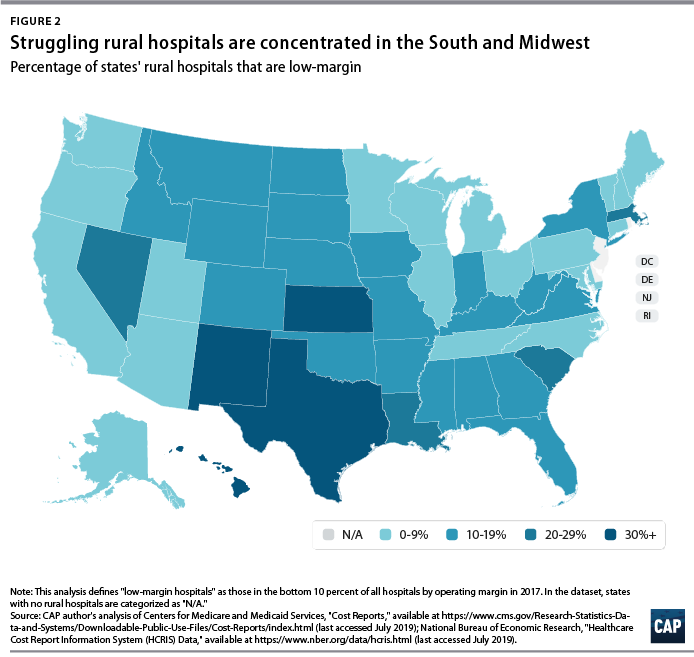

Rural hospitals are less likely to be financially healthy than urban hospitals. In 2017, rural hospitals comprised only 27.9 percent of the hospitals with operating margins in the highest decile but comprised 59.7 percent of the hospitals in the lowest decile. Southern and Midwestern states had the greatest proportion of rural hospitals with low operating margins, mimicking the geographic patterns in hospital closures that the GAO report identified. CAP finds that from 2015 through 2017, rural hospitals were consistently more likely than urban hospitals to fall in the bottom 10 percent of operating margins. CAP’s analysis also confirms that rural hospitals in states that expanded Medicaid had a higher median operating margin (negative 3.4 percent) than those in states that have not expanded Medicaid (negative 5.7 percent).

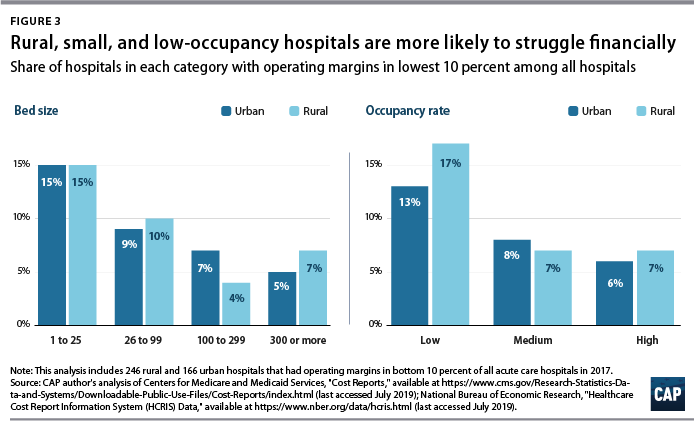

To examine commonalities among the hospitals most vulnerable to closure, CAP analyzed characteristics of the hospitals with low margins, defined as having an operating margin in the lowest 10 percent among all hospitals. Smaller, low-occupancy rural hospitals were most likely to struggle financially: nearly 1 in 6 (15 percent) of hospitals with 25 or fewer beds had low margins, and nearly one-fifth (17 percent) of hospitals with low-occupancy rates had low margins. (See Figure 3)

Emergency departments are on the front lines for rural health

In some emergency situations, hospital closures can be life-threatening, increasing the time and distance patients travel to receive care. Studies show that the probability of dying from a heart attack increases with distance from emergency care,48 and traumatic injuries are more likely to be fatal for rural residents than for urban ones.49

Rural residents are more likely than urban residents to visit the emergency department.50 A shortage of primary care providers; lack of public transportation infrastructure; shortages in preventive care; higher rates of smoking and obesity; and greater prevalence of chronic disease in rural areas all contribute to the greater utilization of emergency room care.51 As a result, emergency departments often stand in as the main source of care for vulnerable and low-income populations, especially for communities that face a shortage of primary care. 52 Among the dozens of rural hospitals that have closed in recent years, some served as the only emergency department in a community, according to MedPAC53

While freestanding emergency departments have proliferated,54 they are not filling the gap for rural emergency care. MedPAC found that, as of 2016, nearly all the country’s 566 stand-alone emergency departments were in urban areas and tended to be located in more affluent communities.55 Researchers at the North Carolina Rural Health Research Program found that the freestanding emergency department model was generally not viable in rural areas of the state due to low patient volumes, high rates of uninsured patients, and provider shortages.56 One limit on the growth of independent freestanding emergency centers is that they are not recognized in Medicare law and are therefore unable to bill the program, unlike hospital-affiliated off-campus emergency departments. 57

Future rural hospital closures would increase the distances that patients travel for emergencies

To better understand how future rural hospital closures could affect access to emergency care, CAP calculated hospitals’ distance to the next-closest hospital-based emergency department. CAP restricted its 2017 HCRIS data sample to the 3,616 acute care hospitals that provide 24-hour emergency services.58 Using addresses or coordinates provided in the HCRIS, CAP mapped each low-margin rural hospital to the next-closest hospital emergency department. Mapping strategies are detailed in the Methodological appendix.

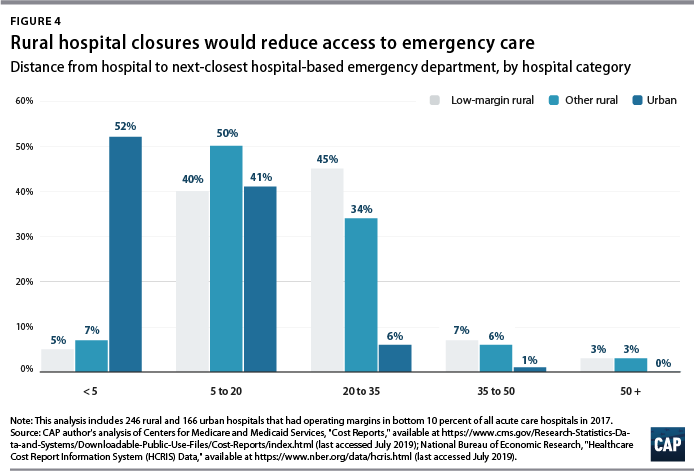

Among the 222 low-margin rural hospitals, more than half (55 percent) were more than 20 miles away from the next-closest hospital-based emergency department, and one-tenth were more than 35 miles away. (See Figure 4). The average distance to the next-closest emergency department was 22 miles.

The disappearance of rural, low-margin hospitals would greatly increase patients’ travel distances for emergency care. Without other resources to fill the gap, some patients might forgo care they need and others would be forced to undertake an even longer journey to receive medical attention.

Policies to improve rural emergency and nonemergency care

As rural hospitals continue to close, it is crucial to preserve access to emergency care for rural Americans. The following section details a series of policy recommendations to support adequate emergency care and address care shortages in rural communities.

Expand Medicaid

Experience to date suggests that rural hospitals in those states that have not yet expanded their Medicaid programs under the ACA would benefit from Medicaid expansion through lower levels of uncompensated care and increased financial sustainability. Medicaid expansion is associated with improvements in health and a wide variety of other outcomes, including lower mortality, less uncompensated care, and lower rates of medical debt.59 According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, about 4.4 million adults would gain Medicaid eligibility if the remaining 14 nonexpansion states expanded their programs.60

Policymakers can also support rural communities and their hospitals by opposing efforts to repeal the ACA. If the Trump administration-backed lawsuit against the ACA were to succeed, 20 million Americans would lose health insurance coverage, and uncompensated care would rise by $50 billion, according to the Urban Institute.61

Create a greater number of rural emergency centers

To preserve access to emergency care, Congress could allow rural hospitals like CAHs to downsize to an emergency department and eliminate inpatient beds without giving up special Medicare reimbursement arrangements. Qualifying hospitals could transfer patients requiring inpatient admission to other hospitals, while continuing to offer some diagnostic imaging and other outpatient services.

One such proposal is the Rural Emergency Acute Care Hospital Act (REACH Act), bipartisan legislation proposed by Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-MN) and Sen. Chuck Grassley (R-IA) that would create rural emergency centers.62 This designation would allow hospitals to provide only emergency care in rural communities and receive Medicare reimbursement at 110 percent of operating costs. Separately, MedPAC has recommended that rural hospitals located more than 35 miles from the nearest emergency department be allowed to convert to freestanding emergency departments while still being reimbursed at hospital rates.63

Institute global budgeting for rural hospitals

Under global budgeting, hospitals are paid a fixed amount rather than having their reimbursements based on the volume and types of services they provide.64 Global budgeting can reduce small, rural hospitals’ financial risk by providing them with a more predictable stream of revenue. In addition, payment reforms that include both hospital and nonhospital care can encourage communities to invest in services that are typically less generously reimbursed, such as preventive care.65

For example, in 2014, Maryland transitioned its acute hospitals from fee-for-service payments to a global budget.66 An evaluation of the global budget program showed that it reduced hospital expenditures relative to trend without transferring costs to other parts of the health care system.67 Future global budgets should emphasize improvements in population health and primary care,68 including ensuring that patients receive care in appropriate settings and reducing the number of avoidable hospital visits.

The Pennsylvania Rural Health Model is the first Medicare demonstration project to test the financial viability and community effects of a global budget for strictly rural hospitals.69 This six-year program aims to smooth out cash flow for 30 rural Pennsylvania hospitals on a monthly basis with the goal of enabling hospitals to meet community needs, especially for substance-use disorder and mental health services.70 With global budgets based on the previous year’s revenues, participating hospitals will have a more predicable stream of revenue. Importantly, the program allows hospitals to share in the savings that result from avoidable utilization.71

Improve transportation for rural residents

The lack of transportation infrastructure can lead rural residents to rely on ambulances and emergency rooms for nonemergency care. In nonemergency situations, patients often cite the lack of affordable transportation as a major barrier to care access.72 In order to fill the gap, payers and policymakers should consider efforts to utilize existing community transit resources for medical transportation or reimburse patients who use ride-sharing services in areas that lack public transit or taxi services. 73 Another option would be to formalize volunteer services for medical transit. Oregon offers a tax credit for volunteer rural emergency medical services (EMS) providers, who provide medical and transportation services analogous to those of volunteer firefighter programs.74 The CMS should also consider policies to better reimburse and expand the use of telehealth in remote areas to reduce patients’ burden of transportation.75 Finally, the CMS should stop approving states’ requests to waive coverage of nonemergency medical transportation (NEMT) requirements under Medicaid.76 NEMT is vital to eligible beneficiaries’ access to care, including appointments for preventive care, chronic disease management, and substance-use disorder treatment.

Strengthen the rural health care workforce

Rural health care provider shortages contribute to poorer access to care and poorer quality of care in rural communities. While 20 percent of the U.S. population lives in rural areas, only 9 percent of primary care physicians practice in rural areas.77 Greater access to primary care providers in rural areas would improve quality of care and health outcomes while also reducing unnecessary emergency department visits.78

One way to assist rural areas would be to encourage health professionals to train and work in underserved communities. Federal funding for physician training should include reimbursements for community-based sites so that medical residents can rotate through nonhospital settings.79 Expanding the National Health Service Corps—which provides scholarships and student loan repayment for professionals who work in federally designated health professional shortage areas—could also help bolster the rural workforce. In addition, changes to immigration policy—such as expanding the Conrad 30 program that funnels immigrant doctors into rural and underserved communities, reforming H-1B visas to benefit high-need communities—could help alleviate rural areas’ shortage of medical professionals.80

Conclusion

Mounting closures of rural hospitals across the country are exacerbating the disparity in health care access between rural and urban areas. The financial vulnerability of the remaining rural hospitals suggests that the trend may continue, leaving shortages in emergency care and other hospital services.

Policymakers should support initiatives that allow remaining rural hospitals the flexibility to tailor their services to meet community needs and improve access to care for rural Americans.

About the authors

Tarun Ramesh was an intern for Health Policy at the Center for American Progress. He is an undergraduate at the University of Georgia studying economics and genetics.

Emily Gee is the health economist of Health Policy at the Center. Prior to that, she worked at U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and at the Council of Economic Advisers at the White House. She holds a Ph.D. in economics from Boston University.

Methodological appendix

CAP analyzed data from the CMS HCRIS data using Stata 15 statistical software. Data were from FY 2017, the most recent year for which the CMS has a complete set of hospital cost filings. CAP downloaded HCRIS databases formatted for Stata from the National Bureau of Economic Research and matched the data with Medicare’s hospital general information database.81 HCRIS reports contain a variable indicating whether the hospital is rural or urban; the CMS defines any hospital outside a metropolitan statistical area as rural.82

CAP used the most recent report filed for each hospital. Although hospitals are required to file annual cost reports, some reports contain more or fewer than 12 months of data. The analysis is restricted to reports that have between 10 and 14 months of data, the “full year” definition that the CMS suggests for analysis.83 CAP then excluded hospitals with data containing missing or apparently erroneous values as well as hospitals with operating margins below the fifth percentile or above the 95th percentile in order to eliminate unreasonable values before identifying the decile with the lowest operating margins. Lastly, CAP restricted its analytic sample to hospitals that had location data valid for mapping in the cost report.

To map hospital-based emergency departments, CAP further restricted the sample to the 3,616 hospitals that had all-hours emergency services. The CMS’s Hospital General Information database indicates whether hospitals provide emergency services.84 CAP then used nearest-neighbor analysis to compute the distance between hospitals.85 Although the computed distances are underestimates, as they do not account for roads, obstructions, or alternate routes, these differences are negligible for the purposes of this analysis.86