In July 2015, Aetna Inc. announced plans to buy Humana Inc. in a $37 billion deal that would merge two of the five largest health insurance companies in the United States. The same month, two more of these five major U.S. insurers—Anthem Inc. and Cigna Corp.—announced plans for a merger. The U.S. Department of Justice, or DOJ, is currently reviewing these mergers to determine whether they violate antitrust laws by reducing market competition; collectively, these four companies cover almost 90 million people. Federal law prohibits mergers when the effect “may be substantially to lessen competition, or to tend to create a monopoly.”

DOJ’s evaluation will assess the mergers in a variety of ways. First, DOJ will look at local markets in which the insurers currently compete and assess whether the merging firms are the best substitutes for each other or primary competitors. For example, it will look at the insurers’ competing products in specific areas. Second, DOJ will consider the overall competitive impact of the mergers.

This issue brief focuses on the potential impact of the proposed Aetna-Humana merger on the Medicare Advantage market. Our analysis finds that the merger would result in greater concentration in already concentrated Medicare Advantage markets. While the combined company would serve 8 percent of all Medicare beneficiaries— including those served by traditional Medicare—it would serve more than one-quarter of Medicare Advantage beneficiaries. For antitrust purposes, Medicare Advantage should be considered a distinct market separate from traditional Medicare because, for a variety of reasons, seniors may not switch easily from Medicare Advantage to traditional Medicare.

Not only would the merger reduce competition in areas where the insurers currently overlap, but it also would foreclose future competition in other areas and markets in which the insurers do not currently compete. For that reason, even if federal regulators require Aetna and Humana to divest parts of their Medicare Advantage business in areas where they overlap, the merger would still reduce competition.

As a result, the Aetna-Humana merger likely would increase premiums for seniors. The Center for American Progress’ analysis finds that in areas where the two insurers overlap, the presence of the second insurer exerts downward pressure on premiums. The competition between the two insurers lowers Aetna’s annual premiums by up to $302 and Humana’s annual premiums by $43. In the absence of this competition, premiums would be higher by these amounts. Under the merger, premiums could increase by even more as a result of the greater market power of the new company.

Regardless of the impact on premiums, the merger certainly would reduce the number of choices in insurance products. What’s more, the merger likely would increase costs to the Medicare program and increase the federal budget deficit because insurer bids likely would rise and the government would retain less in savings.

Despite these potential adverse effects, proponents of the merger make several arguments in its favor, including that the combined company would enhance reform of the health care payment and delivery system and improve the quality of care. However, these arguments do not stand up under close scrutiny. At best, the effects of the merger would be highly uncertain for consumers and the broader health care system. At a time of great change in the health care system, prudence would dictate extreme caution in allowing the merger to proceed—especially given that it could not be undone and its potentially serious adverse effects would be irreversible.

The effects of health insurer mergers

Theoretically, insurer mergers could have two very different results. First, they could raise premiums—if the merger reduces competition, allowing health insurers to set higher prices. Second, if a merger strengthens insurers’ bargaining power with providers, it could in fact lower prices. Similarly, a merger also has the potential to result in efficiency gains, including from economies of scale, and savings that insurers could pass along to consumers in the form of lower premiums.

Researchers have not studied the impact of mergers specifically on Medicare Advantage premiums, but the available research on insurance consolidation—as summarized below—is applicable to the private Medicare Advantage market and shows that insurer consolidation generally leads to higher premiums. And competition in health care markets leads to lower premiums. Health insurance markets also already have significant barriers to entry that can reduce competition.

Consolidation increases premiums

Research shows that consolidation among health insurers can decrease competition, in turn increasing costs for consumers. First, when competitors merge to form a new, larger business, that enlarged company may raise prices on its own if it no longer faces market competition. Second, a merger can increase the likelihood that remaining businesses can act in a coordinated way to undermine competition.

The primary example of research on health insurance consolidation assessed the effects on the private insurance market of a 1999 merger between Aetna and Prudential Healthcare. Because these two national insurers were present in most local insurance markets, their merger had a broad impact. The analysis found that the merger had statistically significant effects in raising premium prices. Overall, researchers found that the merger, due to the increase in concentration in the local markets, resulted in premiums that were 7 percent higher by 2007 than they would have been if local market concentration had remained the same as prior to the merger.

Another study looked at a merger in 2008 between Sierra Health Services and UnitedHealth Group and the effect on premiums in the small-group insurance market, or employers with fewer than 50 employees. Comparing two markets in Nevada to control markets in other states, the study found that small-group premiums in the Nevada markets increased by 13.7 percent in the year after the merger.

Competition lowers prices

Research also demonstrates that competition in health insurance markets reduces premium costs. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, or HHS, has quantified the effect that competition in the Affordable Care Act’s marketplaces had on premiums in 2014. Specifically, the premium of the second-lowest-cost silver plan— the plan against which the premium tax credits available through the marketplaces are calculated—decreased 4 percent for each additional insurer participating in a rating area. HHS also found that premium growth from 2014 to 2015 for the second-lowest-cost silver plan decreased by 2.8 percentage points for each net gain of one issuer in a county.

Two recent studies corroborate the findings that competition is associated with lower premiums. First, researchers found that in the federally facilitated marketplaces, the addition of one insurer in a county was associated with a 1.2 percent lower premium for the average silver plan and a 3.5 percent lower premium for the second-lowest-cost silver plan from 2014 to 2015. A second group of researchers found that between 2014 and 2015, premiums for all plans in a rating area dropped 1.4 percent, and the two lowest-cost silver plans and the lowest-cost bronze plan dropped 2.2 percent for each additional issuer, holding all other factors constant.

Another study found similar effects by examining the effect on premiums when insurers did not participate in the marketplaces. In 2014, only 54 percent of the three largest insurers in each state participated in the state’s marketplace, and UnitedHealthcare— the nation’s biggest insurer—did not participate in any. The researchers found that if UnitedHealthcare had participated, the premium for the second-lowest-cost silver plan would have been lower, on average, by 5.4 percent. Furthermore, if all insurers who were active in each state’s individual market had offered marketplace plans, premiums would have been 11.1 percent lower.

Additional research on the Affordable Care Act’s marketplaces provides more evidence that larger insurers have the power, and use it, to raise prices. A recent study looked at the changes in health insurance premiums charged by individual insurers in states with federally facilitated and state-partnership marketplaces. The study’s results show that between 2014 and 2015, the largest insurers in each state raised premiums 75 percent more than the other insurers in the state, even though the large insurers’ costs were not growing faster.

A recent paper also investigated the impact of insurer competition on premiums in the large-group commercial health insurance market in California. The researchers simulated the effect on premiums of removing an insurer from the market. They found that removing an insurer led to increases in premiums, and also possibly hospital prices, on average.

Barriers to entry

In addition, there are already substantial barriers to entry in private health insurance markets that discourage insurers from entering a market, therefore reducing competition. These barriers include building provider networks, negotiating competitive rates with providers, establishing a reputation with customers in the local market, and creating economies of scale in areas such as information technology. These barriers are only amplified by consolidation, which creates large companies with greater economies of scale and provider networks. As Leemore Dafny, an expert in insurance consolidation, testified recently before the Senate Judiciary Committee:

In light of the impediments to de novo entry, consolidation even in non-overlapping markets reduces the number of potential entrants who might attempt to overcome price-increasing (or quality-reducing) consolidation in markets where they do not currently operate.

The Medicare Advantage program

Medicare Advantage is a type of Medicare coverage that allows seniors to opt out of traditional Medicare and enroll in a private insurance plan. The Medicare program pays each private plan a monthly amount per enrollee to provide Medicare benefits.

In 2015, 16.8 million Americans were enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans, or 31 percent of all Medicare enrollees. These numbers have increased from 11.1 million enrolled—24 percent of the Medicare population—in 2010. Medicare Advantage is an attractive insurance market for insurers because of the country’s aging population and the increasing percentage of seniors choosing these plans.

Medicare Advantage bidding process

Medicare pays Medicare Advantage plans under a bidding process. Each Medicare Advantage plan submits a bid to Medicare in the amount of the average cost to the plan of providing traditional Medicare benefits to a typical beneficiary in the plan’s area. The plan’s bid is then compared with a benchmark. If the plan’s bid is lower than the benchmark, the government provides a rebate amount to the plan that is a portion of the difference between the bid and the benchmark. Plans must spend their rebate on extra benefits, reduced cost sharing, or lower premiums. If the plan’s bid is greater than the benchmark, beneficiaries pay that difference as an added premium.

Medicare Advantage enrollees still pay the regular Medicare Part B premium like all other Medicare enrollees and also may have to pay an additional monthly premium charged by the Medicare Advantage plan. However, Medicare Advantage plans generally have lower cost sharing than traditional Medicare and provide coverage for prescription drugs. By contrast, Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in the traditional Medicare program typically enroll in a separate Medicare prescription drug plan, a so-called Medigap supplemental health care plan that covers out-of-pocket costs, supplemental retiree coverage from a former employer or union, or some combination of plans, in order to gain comparable coverage.

In 2015, the range of Medicare Part B premiums was $104.90 to $335.70 per month, with most beneficiaries paying $104.90. The average added Medicare Advantage premium in 2015 was $38 per month. Most Medicare Advantage beneficiaries have the choice of a plan with zero additional premium, but the availability of this option has declined from 94 percent in 2009 to 78 percent in 2015. Medicare Advantage enrollees’ out-of-pocket costs also are increasing. For example, in 2015, the average plan limit on out-of-pocket costs for covered services was $5,037, which is $240 more than in 2014.

Competition in Medicare Advantage markets

Nearly all Medicare Advantage markets across the United States already lack competition.

The Herfindahl-Hirschman Index, or HHI, is a standard measure of market concentration and competition, and it is used to evaluate potential antitrust implications of market acquisitions and mergers. Nonconcentrated markets have an HHI below 1,500 points, moderately concentrated markets have an HHI between 1,500 and 2,500 points, and the HHI in highly concentrated markets is more than 2,500 points. A recent Commonwealth Fund analysis found that 97 percent of Medicare Advantage plan markets in U.S. counties are highly concentrated. Even among the 100 counties with the most Medicare beneficiaries, 81 do not have competitive markets.

Similar to the research on competition cited above, competition in the Medicare Advantage market has been found to decrease premiums. The first empirical study of competitive bidding in Medicare Advantage found that each additional insurer in a market lowered bids by $1.28 and increased rebates by $0.83, meaning that when competition exists, plans have an incentive to bid lower and offer higher rebates in order to attract enrollees. Furthermore, this analysis also found that when Medicare raised its benchmarks—even when a plan’s costs remained the same—the plan submitted a higher bid. In other words, the plans pocketed part of Medicare’s higher payments instead of passing them along as rebates to beneficiaries. If Medicare Advantage were truly a competitive market, additional payments to plans would not change bids because bids should only be as high as the plan’s cost of insuring beneficiaries.

Effect of the Aetna-Humana merger on the Medicare Advantage market

The Aetna-Humana merger would affect a substantial percentage of Medicare Advantage enrollees. Currently, Humana has 19 percent of the Medicare Advantage market, with Aetna holding 7 percent. A combined company would surpass UnitedHealthcare, which is currently the largest Medicare Advantage insurer, with 20 percent of the market share.

The proposed merger would further increase concentration and decrease competition in Medicare Advantage markets, which in turn would increase premiums and Medicare program spending.

Increased market concentration

The Kaiser Family Foundation finds that the Aetna-Humana merger would include at least half of all Medicare Advantage enrollees in 10 states and at least two-thirds of all enrollees in five states. The American Hospital Association also has found that the Aetna-Humana merger would increase market concentration; the HHI would increase by at least 100 points in 1,083 markets and more than 200 points in 924 markets, and the postmerger HHI in these markets would be more than 2,500 points—signifying highly concentrated markets. The American Hospital Association also reports that the merger would affect more than 2.7 million Medicare Advantage enrollees.

The Kaiser Family Foundation finds that the Aetna-Humana merger would include at least half of all Medicare Advantage enrollees in 10 states and at least two-thirds of all enrollees in five states. The American Hospital Association also has found that the Aetna-Humana merger would increase market concentration; the HHI would increase by at least 100 points in 1,083 markets and more than 200 points in 924 markets, and the postmerger HHI in these markets would be more than 2,500 points—signifying highly concentrated markets. The American Hospital Association also reports that the merger would affect more than 2.7 million Medicare Advantage enrollees.

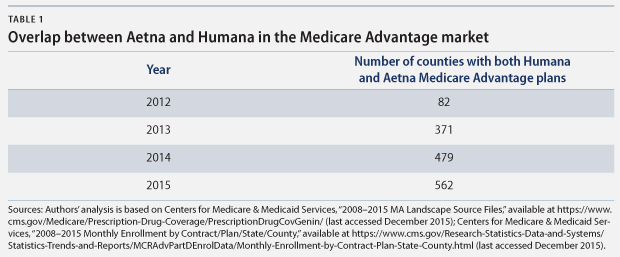

The proposed Aetna-Humana merger would increase concentration in Medicare Advantage markets where both insurers currently offer plans. A Center for American Progress analysis of data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services finds that in 2015, Aetna and Humana both offer Medicare Advantage plans in 562 counties in 28 states. This is almost 20 percent of all of the counties and county equivalents in the United States. The range of the number of counties with both issuers varies significantly by state—from just 1 county in Arizona and Nevada to 59 in Pennsylvania and 67 in Missouri. (see Table B1 in Appendix B) This overlap also has dramatically increased in recent years—from 82 counties in 2012 to 562 counties in 2015.

Importantly, this significant increase in overlap in recent years suggests that competition between the two insurers is increasing and that they would continue to enter each other’s markets if they did not merge; a merger would foreclose this potential future competition. In the 562 counties where the insurers currently do overlap, not only would they no longer compete with each other, but other insurers also may be dissuaded from entering these markets because the comparative advantage of the large combined insurer would be too great.

Higher premiums

This increase in concentration, and corresponding decrease in competition, from the proposed merger would affect Medicare Advantage premium prices. CAP’s analysis of the premiums offered by Aetna and Humana in overlapping markets from 2008 to 2015 quantifies how the current competition between Aetna and Humana puts downward pressure on premiums. Using regression analysis and controlling for year, the type of plan, and state, CAP finds that when Humana offers a Medicare Advantage plan in the same county as Aetna, Aetna’s average premium is lower, and vice versa.* These effects are large and highly statistically significant. (See Appendix A for the methodology and Appendix B for the regression tables)

Effect of competition

In counties where Aetna and Humana compete:*

- Aetna’s Medicare Advantage annual premiums are $155 lower

- Humana’s Medicare Advantage annual premiums are $43 lower

* Compared with premiums in counties where they do not compete and controlling for different effects by state

Specifically, in counties where Humana offers a plan to compete with Aetna, Aetna’s average annual premiums are $302 lower than in counties where Humana does not offer a plan. A more conservative estimate that controls for different effects by state finds that Aetna’s average annual premiums are $155 lower in counties where it competes with Humana.** This downward pressure from competition between the two insurers also affects Humana’s premiums. Where the two insurers are competing, Humana’s average annual premium is $43 lower, controlling for state effects, than where they are not competing.

These results demonstrate how much premiums could increase if the merger is approved. Furthermore, a combined company actually could raise premiums even higher than this analysis suggests because of the company’s greater market power.

Higher Medicare program spending

The primary concern regarding the proposed merger is the impact on consumers, but there also would be adverse effects on the Medicare program and taxpayers, as well as the federal deficit. Medicare program spending will increase if the new, significantly larger combined insurer increases its bid amounts, which is likely, and if fewer bids are below the benchmark rate—meaning that the federal government retains fewer rebates. First, even if the new plan’s bid is below the benchmark amount, it is still likely to be higher than the premerger bid amounts. Second, when there are fewer plans, it is a reasonable assumption that fewer plans will bid below the benchmark rate. In this scenario, Medicare’s costs would increase from the current payment amount, which is below the benchmark amount, to the benchmark amount.

Higher Medicare program spending

An example can help illustrate how a merger that results in higher premium prices could increase government spending on Medicare. In this example, we assume that the bids for the combined company postmerger will be the higher of the bids of the two individual insurers premerger. These numbers are purely illustrative.

Benchmark:* $752.50

Premerger:

Aetna bid: $740

Humana bid: $750

Government spending: Government spending equals the bid amount plus a rebate to the insurer that is between 50 percent and 70 percent of the difference between the bid and the benchmark, depending on the plan quality ratings. Therefore, the government will pay a monthly rate per beneficiary of $746.25 to Aetna and $751.25 to Humana—for an average of $748.75 per beneficiary.**

Postmerger

Bid by combined Aetna-Humana insurer: $750

Government spending: $751.25 to combined insurer

Effect of the merger

Medicare’s monthly payment increased from an average of $748.75 per beneficiary premerger to $751.25 per beneficiary postmerger. Even though the combined company is still bidding below the benchmark rate, the government spends more money per beneficiary.

* $752.50 is the average local monthly benchmark in 2015, weighted by enrollment in different types of plans by county. See Kaiser Family Foundation, “Medicare Advantage: Local Benchmarks (weighted),” available at http://kff.org/medicare/state-indicator/local-benchmarks-weighted/ (last accessed December 2015).

** $746.25 is calculated as $740 + 0.5*(752.50-740). $751.25 is calculated as $750 + 0.5*(752.50-750), where 0.5 is the portion of the difference between the bid and the benchmark that the insurer keeps as a rebate in the above example.

Effect on the individual health insurance market

This issue brief focuses on Medicare Advantage and how the proposed merger would reduce competition and increase premiums in that market. However, the merger also would have significant effects on the individual health insurance market, where there is also substantial overlap between Aetna and Humana. In eight states, Aetna and Humana both offer marketplace plans in the same rating areas. Aetna is already the largest issuer on the marketplaces, and with the acquisition of Humana, it would increase its enrollment in the marketplaces to almost 17 percent of all those who have purchased marketplace plans. With the announcement by UnitedHealth Group that it is considering an exit from the marketplaces, this share and the effect on competition could be even greater.

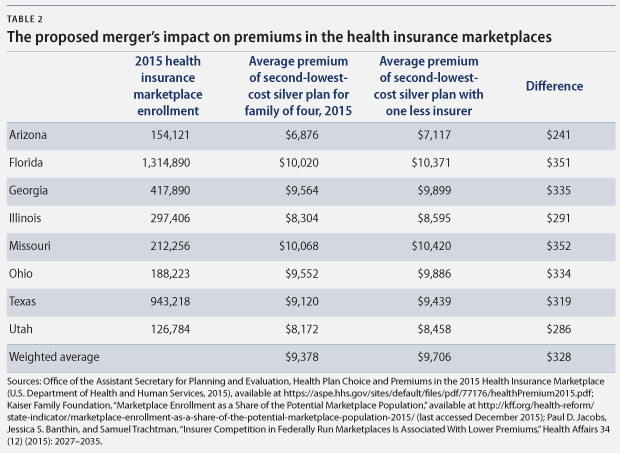

Even though the rating areas in which Aetna and Humana currently compete would have other competitors should the proposed merger go through, premiums on the marketplaces still are likely to increase. Recent research has found that the average premium of the second-lowest-cost silver plan in 2015 was 3.5 percent lower for every additional insurer participating in a rating area. This effect suggests that in 2015, if a merger had removed one insurer from the eight states where Aetna and Humana currently compete, premiums for the second-lowest-cost silver plan could have been an average of $328 higher for a family of four.

Other considerations

Proponents of the merger point to potential upsides of a combined company to justify the merger. However, these arguments do not provide sufficient assurances that they will benefit consumers.

Would a merger enhance payment reform and value?

Aetna and Humana have argued that the greater market share and resources of the combined company would increase their focus on payment reform. Many Medicare Advantage plans largely operate in the fee-for-service system, where health care providers are paid separately for each item and service furnished to a patient, which encourages a higher volume of services and less coordination of care. Moving more Medicare Advantage plans to alternative payment models, under which health care providers are accountable for the quality and cost of care for each patient, would help constrain health care costs and improve quality.

It is possible that payment reform could be more effective when done by a bigger insurer with greater market share because providers would face stronger incentives to change the way they deliver care. However, traditional Medicare, which still has 69 percent market share, is already testing and implementing payment reforms. If traditional Medicare follows through on payment reform—and if all Medicare Advantage insurers also adopt such payment reforms—the combined signal and incentives for providers will be far greater than if a single large insurer adopts payment reforms.

Moreover, Aetna and Humana are already two of the five largest insurers with vast resources, so it is hard to see why combining the companies is necessary to adopt payment reforms. There is also no evidence that larger insurers are more likely to implement innovative payment models, nor any assurance that the combined Aetna-Humana company would do so. In addition, there is an argument that more competition could lead to more innovative ways to lower costs and improve care, and the merger would reduce this competition.

Aetna also points to its plans to build an “Optum-like unit” within the combined company as a positive result of the merger. Optum is a part of UnitedHealth Group that provides health services such as data analytics, clinical consulting, and drug management.*** Optum serves clients across the health care system, including the related company of UnitedHealthcare, and it has been very profitable for UnitedHealth Group. Humana controls the fourth-largest pharmacy benefit manager in the country, which would enable Aetna to create a unit similar to Optum.

As noted above, Aetna and Humana are already massive insurers with significant resources, so it is not clear why a merger is necessary for their efforts to build an Optum-like health services division. Moreover, to date, Optum has not improved the quality of UnitedHealthcare’s Medicare Advantage plans. Medicare Advantage plans are rated on quality and performance measures. In 2015, the average star rating for all plans weighted by enrollment is 3.92 out of a possible 5. However, UnitedHealthcare’s Medicare Advantage plans have a below-average overall star rating of only 3.23. By contrast, Aetna’s rating is 4.13, and Humana’s is 4.06. At least in this case, bigger is not better.

Insurers also commonly argue that mergers are necessary to counter the increasing consolidation among health care providers because larger insurers can exert greater bargaining power against providers to keep prices low. However, the health care system cannot engage in such an arms race. With fewer insurers and fewer providers, there is less of an incentive to negotiate lower costs. If there is only one dominant provider and one dominant insurer in an area, neither will have any pressure to negotiate lower prices, and beneficiaries, taxpayers, and Medicare will all pay the excess. The only consumer friendly remedy to the concerning trend of provider consolidation is to also apply greater scrutiny to those mergers. Indeed, the Federal Trade Commission—which oversees mergers of providers—recently moved to block a merger of two health systems in South Central Pennsylvania.

Would consumer protections be sufficient?

Divestitures are a method that prevents a merger from creating too much concentration in certain markets. Regulators could ask Aetna or Humana to sell its business in certain markets to an outside competitor to maintain competition. Two previous mergers, UnitedHealth-Sierra and Humana-Arcadian, were approved on the condition that they divest parts of their Medicare Advantage business.

But the already high concentration in Medicare Advantage markets and the barriers to entry may mean that competitors to which Aetna and Humana could divest may not exist. Moreover, the UnitedHealth-Sierra and Humana-Arcadian mergers only affected competition in a few markets—two counties for the UnitedHealth-Sierra merger and 45 for the Humana-Arcadian merger—which is far fewer than the number of counties affected by this proposed merger. Yet the UnitedHealth-Sierra merger still resulted in significant premium increases in the affected markets, even with divestiture. Most importantly, divestitures would do nothing to preserve the possibility of future competition in markets where the two insurers currently do not compete.

Insurers also point to the medical loss ratio, or MLR, as a protection that ensures that seniors will benefit from the merger. The MLR requires insurers to spend most of their revenue from premiums on medical expenses for consumers, thus guaranteeing that consumers see a return on their premium payments. Medicare Advantage plans must spend 85 percent of their revenue on medical expenses.

Although the MLR provides some protection against a merged company charging inflated premiums, this protection is not sufficient. If it were, then every merger between two health insurance companies would be in consumers’ interest. But it is entirely possible that insurers in the Medicare Advantage market are already satisfying the MLR standard. In the most comparable market, the large employer market, 77 percent of plans were already meeting the 85 percent threshold before it went into effect. If two merging insurers both have MLRs of 90 percent, for example, and the merged company jacks up premiums such that the resulting MLR drops to 85 percent, then consumers will have been harmed. Nor does the MLR protect against premium increases that reflect higher medical costs.

Lastly, the MLR is not plan specific but instead a broad measure based on an insurer’s aggregate Medicare Advantage spending at the state and market levels. Therefore, individual plan offerings may not necessarily meet the MLR threshold, and a merger could allow insurers to offset a low MLR in one area with a high MLR in a different area.

Would traditional Medicare act as a safety valve for seniors?

Seniors who face higher costs due to the merger may be able to switch from Medicare Advantage to traditional Medicare. But past experience suggests that people tend to stick with their plan during the open enrollment period—even when premiums or other costs go up. In the Medicare prescription drug program, for example, a small fraction of seniors switch plans—and most seniors who face large premium increases do not switch plans. Many may not know that they could get a better deal if they switched their type of Medicare coverage.

Traditional Medicare covers care provided to a Medicare beneficiary by any hospital, physician, or other provider that accepts Medicare patients anywhere in the country. But traditional Medicare also has high cost-sharing requirements and no limit on outof-pocket spending, so many seniors enrolled in traditional Medicare purchase supplemental coverage, or Medigap plans, to protect themselves from higher, unpredictable costs. But when seniors switch from Medicare Advantage to traditional Medicare, most states allow plans that provide supplemental coverage to deny coverage to beneficiaries or exclude coverage of pre-existing conditions—except when a Medicare Advantage plan terminates or a senior moves. Many beneficiaries may not be aware of these limits. These restrictions would perhaps increase out-of-pocket costs for switching seniors and may make traditional Medicare an unviable option.

Lastly, premiums may increase due to the merger but still be lower than costs under traditional Medicare. Also, Medicare Advantage plans have the ability to limit their networks of medical providers, allowing them to continue to offer lower premiums than traditional Medicare for the same benefits. Seniors who do not want or need to be able to go to any provider may therefore stay in Medicare Advantage rather than switching to traditional Medicare.

Because the combined company would price its plans to maximize premiums without encouraging a widespread migration to traditional Medicare, many seniors would be stuck with higher costs. As the American Medical Association wrote, “Seniors are not likely to switch away from Medicare Advantage plans to traditional Medicare in sufficient numbers to make an anticompetitive price increase or reduction in quality unprofitable to a Medicare Advantage insurer.”

Conclusion

The Medicare Advantage market is currently highly concentrated. CAP’s analysis of the overlap between Aetna and Humana in Medicare Advantage markets adds to other analyses that show that the proposed merger between the two companies would only exacerbate this trend, likely resulting in higher premiums for seniors and higher costs for the Medicare program. Tellingly, at a Senate Judiciary Committee hearing on the proposed merger, the CEO of Aetna would not guarantee that savings from the merger would be passed along to consumers until pressed three times.

This analysis of one health insurance market in one of the two proposed mergers is just part of the broader analysis of both health insurance mergers, which will be evaluated for their combined effect on potential future competition in all markets. But all of the available evidence suggests that the bar should be very high for approving these mergers and that they should be stopped absent clear and compelling evidence that they will benefit consumers.

Topher Spiro is the Vice President for Health Policy at the Center for American Progress. Maura Calsyn is the Director of Health Policy at the Center. Meghan O’Toole is a Policy Analyst for the Health Policy team at the Center.

Text footnotes

* We also control for the presence of UnitedHealthcare in these markets because it is currently the largest Medicare Advantage insurer.

** We use fixed effects estimation because we assume that premiums may be correlated with the state in which plans are offered. Fixed effects estimation controls for variation within groups—the state in this case. We also use clustered standard errors by state.

*** UnitedHealthcare is the other part of UnitedHealth Group, which provides health care coverage and benefits. See UnitedHealth Group, “About UnitedHealth Group,” available at http://www.unitedhealthgroup.com/About/Default.aspx (last accessed December 2015).

Please see the PDF for the Methodology and Appendix tables.