Next year, the National Park Service will celebrate its centennial anniversary—marking 100 years of dedication to creating a system of unparalleled national parks and monuments that attracts visitors from around the world. As America’s National Park System enters its second century, its viability and relevance will depend not only on the National Park Service’s ability to withstand challenges—such as a changing climate, increased developmental pressures, and decreased federal funding—but also on how well Americans connect to their national parks. The National Park Service Organic Act, signed by President Woodrow Wilson in 1916, ensures that U.S. national parks are managed carefully so that future generations continue to experience places such as the Grand Canyon and Yellowstone in largely the same condition as they are today. However, work remains to build a system of national parks and monuments that tells the stories of all Americans by reflecting the full scope of the nation’s history and meeting the demands of a diverse population.

In an issue brief released last year, the Center for American Progress found that although the United States is home to more than 450 national parks and monuments, less than one-quarter have a primary focus on women, communities of color, or other traditionally underrepresented groups. Not a single unit of the National Park System has a primary focus on the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender, or LGBT, community, and until the recent designation of the Honouliuli National Monument, only two had a primary focus on Asian Americans.

The story told by the parks and monuments already included in the National Park System does not present a complete picture of the nation’s rich and diverse history. With U.S. demographics rapidly changing—such that no single race or ethnicity will constitute a majority of the U.S. population by as early as 2044—Congress and the president should work to conserve places that better reflect America’s diverse population and help engage new generations to visit and explore their shared heritage and resources.

CAP’s most recent review of National Park System designations reveals three main conclusions:

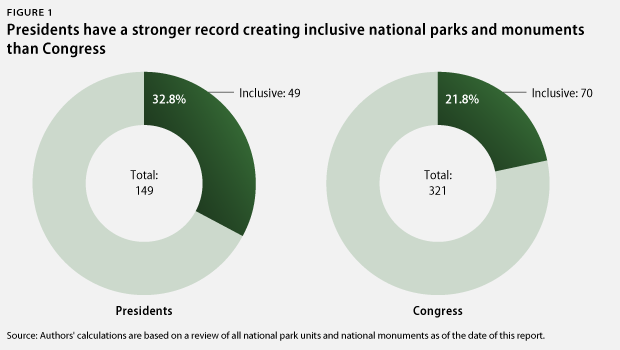

- Presidents have been more effective than Congress at designating inclusive national monuments and parks that tell the stories of underrepresented communities. Thirty-three percent of all designations by presidents are inclusive, compared with only 22 percent of all designations by Congress.

- Recent congressional leadership has been unable to pass legislation to increase inclusivity in the National Park System, focusing instead on preventing President Barack Obama from designating new national monuments.

- Over the past 25 years, U.S. national parks and monuments have become more inclusive but still do not adequately reflect the country’s diversity. However, there are directed actions that Congress can take to fill these gaps and build a National Park System for all Americans.

This issue brief examines the attention given by presidents and Congress to building a more inclusive National Park System.

Presidents have a stronger record than Congress in designating inclusive national parks and monuments

Over the past 25 years, both presidents and Congress have become more adept at promoting diversity through national parks and monuments. Executive action, in particular—under the Antiquities Act of 1906—has proven to be a more effective tool for achieving this goal than Congress enacting legislation.

The Antiquities Act is critical to protecting the nation’s most cherished places as national monuments. It was the first law passed to provide overall protections for cultural and natural resources, setting the tone for the country’s national historic preservation and conservation policy. Sixteen different presidents of both political parties have used the Antiquities Act more than 100 times to designate national parks and monuments.

CAP’s review of all national park units and monuments established since 1872—including monuments managed by the U.S. Forest Service, the Bureau of Land Management, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service—highlights that presidents tend to put more weight on establishing national parks and monuments that promote inclusivity than Congress does. CAP looked at all national park units that have been designated to date and found that 49 of 149 designations by presidents—or 33 percent—were inclusive; this is compared to only 22 percent—70 out of 321—of all congressional designations. These estimates suggest that presidents put more weight on diversity when protecting treasured places.

For example, President Obama singularly has declared 16 national monuments, nine of which have a primary focus on engaging and telling the stories of underrepresented communities, including the Pullman National Monument and the César E. Chávez National Monument. This accomplishment is illustrative of the Obama administration’s commitment to building a network of parks and monuments reflective of the nation’s rich and varied heritage.

Congressional roadblocks to increasing inclusivity

Congress is in a unique position to promote an inclusive system of national parks and monuments with which all Americans can identify. Congress has the authority to enact legislation that designates inclusive parks and monuments, and it controls the purse strings that provide resources for these areas. Traditionally, Congress has readily protected national parks, monuments, and historic sites—designating 321 national park units since 1872. However, some members of Congress have actively and effectively opposed the protection of these special places in recent years, placing little to no emphasis on designating national park units that have a primary focus on traditionally underrepresented communities. Congressional opponents of conservation and historic preservation also have attempted to create roadblocks that, if enacted, would limit the ability of current and future presidents to use the Antiquities Act to designate new national monuments.

One of the most effective ways that Congress can recognize diversity in the National Park System is to enact legislation that either expands or creates new national parks and monuments. Nevertheless, in the past five years, Congress has only established six national park units—barely one per year. Prior to 2010, Congress was designating units at double the current pace.

A review of bills in the 113th Congress, which covered 2013 to 2014, indicates that at least 100 bills to designate or expand units of the National Park System were introduced in the U.S. House of Representatives and Senate, but the majority of these bills never made it to the floor for a vote. In fact, only seven proposals establishing new national park units were passed by Congress as amendments to the National Defense Authorization Act of Fiscal Year 2015, four of which were intended to reflect underrepresented communities. The same pattern is materializing in the 114th Congress. To date, not a single bill to designate inclusive national parks or monuments has passed Congress, let alone legislation to expand the National Park System as a whole.

In particular, the 114th Congress has not yet taken action to address the fact that America’s best parks program, the Land and Water Conservation Fund, or LWCF, is set to expire in September 2015. The program, created in 1965, uses royalties paid by offshore oil and gas companies to fund the creation and protection of parks. The LWCF is authorized annually at $900 million but has been fully funded by Congress only once since its creation. Without swift congressional action to reauthorize this program before September, one of the nation’s most effective conservation programs will disappear.

Efforts by current congressional leaders to prevent President Obama from creating new national monuments are exacerbating the problem. In particular, Republican leaders in the 113th and 114th Congresses have endeavored to block the president from designating any new national monuments without congressional approval.In the 113th Congress, there were at least 12 bills introduced that would have undermined the Antiquities Act, including a bill sponsored by Rep. Rob Bishop (R-UT) to limit the number of monument designations that presidents can make per term. Similarly, the 114th Congress already has introduced at least 13 proposals to block the creation of new national monuments.

LGBT designations

Both Congress and the executive branch have an opportunity to recognize the contributions and impact of the LGBT community through the selection of new sites that celebrate its population and history. These designations also would provide an economic benefit to areas where they are located. In fact, every $1 invested in the National Park System generates $10 in economic activity, totaling nearly $30 billion in revenue for 2014.

The U.S. Department of the Interior took a good first step toward recognizing the LGBT community with the recent designation of the Henry Gerber House in Chicago, Illinois, as the second LGBT National Historic Landmark. However, there currently no National Park System units or national monuments dedicated to the history of the LGBT community. But individual states have acted to weave the experiences of LGBT communities into the national narrative. For instance, the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission recognized a series of annual LGBT rights protests with a marker in front of Philadelphia’s Independence Hall in 2005. In 2009, the District of Columbia granted landmark status to the home of Frank Kameny, who became a pioneer for LGBT rights after he was fired from his government job and took his case to the U.S. Supreme Court. These sites demonstrate the ways in which the LGBT community’s stories can be told.

Congress and the Obama administration should designate new parks and monuments to commemorate the challenges faced by this community and celebrate their achievements, which represent advancements for the nation as a whole. In 2014, the National Park Service announced that its theme study would focus on identifying places and events that tell the story of the LGBT community. This action holds promise, and advocates have independently identified several key sites in LGBT history that are worthy of consideration—including the oldest gay bar in Manhattan, which was the site of a “sip-in” that sparked media coverage of the gay rights movement; a brownstone on New York City’s West 22nd Street that served as the organizational hub of the Gay Men’s Health Crisis to fight the HIV/AIDS epidemic; the first gay and lesbian bookstore in America; and Harvey Milk’s campaign headquarters, among others.

5 steps for Congress to create a more inclusive National Park System

CAP’s review of national park and monument designations in the past 25 years found that—with the exception of the 113th and 114th Congresses—the executive and congressional branches are beginning to put greater emphasis on protecting places that reflect America’s diversity. A previous CAP issue brief indicated that only 24 percent of all national parks and monuments had a primary focus on women or underrepresented communities. However, of the 106 national parks and monuments designated by Congress and presidents in the past 25 years, 40 sites—38 percent—have a primary purpose of recognizing underrepresented communities. A review of designations for the past 10 years showed even more progress: 17 of 39 national parks and monuments—or 44 percent—are inclusive. This trend demonstrates a steady increase in inclusive designations, indicating that as time has passed, presidents and congressional legislators have both placed a greater focus on designating special places that are reflective of the country’s changing demographics.

While this analysis shows progress in the number of inclusive designations since Yellowstone was established as America’s first national park in 1872, federal policymakers still need to address remaining gaps in the National Park System. The Obama administration has actively increased inclusivity in the National Park System through monument designations and Heritage Initiatives launched by the National Park Service that seek to increase inclusivity so that the contributions of all Americans are “recognized, preserved, and interpreted for future generations.” These initiatives include projects dedicated to the heritage of Latinos, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, women, and the LGBT community, among others. However, Congress needs to do its part to accelerate this progress. Congress can take the following five steps to boost inclusivity in the National Park System.

1. Pass legislation to establish new, inclusive national parks and monuments

One of the most powerful and fundamental tools Congress has to promote diversity in the National Park System is its ability to enact legislation. Congress should propose a package of conservation bills with the goal of establishing a system of protected lands and historic places that reflects the contributions of all Americans and the nation’s diversity.

2. Form a caucus or working group to promote inclusivity in the National Park System

The creation of a congressional member organization, such as a congressional caucus or working group, is an effective organizing tool that members of Congress can use to promote policy ideas and exchange information in order to increase inclusivity in the National Park System. Congressional member organizations are used frequently for this purpose. In fact, in the 113th Congress, there were 336 organizations formally registered with the House of Representatives—covering issues ranging from baseball to biofuels.

Forming a caucus or working group dedicated to inclusivity in the National Park System would help coordinate embers’ efforts on this issue. The caucus could help identify inclusive areas that deserve designation, determine pending legislation that should be advanced, and assess additional ways that Congress can improve its role in designating inclusive National Park System units. The 114th Congress currently has a National Parks Caucus, which also could provide a forum to engage on this issue.

3. Hold hearings to highlight the need for inclusivity and identify areas for designation

The Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee’s Subcommittee on National Parks and the House Natural Resources Committee’s Subcommittee on Federal Lands both have jurisdiction over the National Park Service and are “responsible for all matters related to the National Park System, U.S. Forests, public lands, and national monuments.” These committees can hold hearings to explore the lack of inclusivity in the National Park System and find solutions to fix the problem. Hearings could examine why designations have not kept pace with evolving American culture and identify possible areas for inclusive national park and monument designations. Field hearings held in the proposed locations for new, inclusive designations would allow members of Congress to experience directly and understand the importance of these designations. These types of hearings would raise the visibility and public awareness of the issue.

4. Direct the secretary of the interior to conduct special resource studies

Special resource studies are a useful tool that Congress could employ to further identify areas that reflect the diverse history of the United States. The secretary of the interior conducts these studies, which assess the national significance, suitability and feasibility, and other management options of an area that contains either natural or cultural resources.

One example of this tool in action is the authorization of three noteworthy special resource studies for underrepresented communities passed as part of the National Defense Authorization Act. These studies will examine the Buffalo Soldiers; the West Hunter Street Baptist Church, a meeting place during the civil rights movement; and New Philadelphia, Illinois, the first American town founded by an African American. Special resource studies provide an opportunity for Congress to support the administration’s commitment to identifying lands in need of protection that are also places of importance to historically underrepresented communities.

5. Commission a Congressional Research Service report

A member of Congress or a committee of jurisdiction can request that the Congressional Research Service, or CRS, analyze inclusivity in the National Park System and issue a report that provides recommendations to increase inclusivity. A CRS report would provide a baseline accounting of current inclusive designations to better track progress in this area.

Conclusion

With these key steps from Congress, federal policymakers can further shape the National Park System to reflect the changing demographics of the United States. The National Park Service’s centennial anniversary next year provides an opportunity to rethink the inclusivity of our country’s national parks and monuments. Now is the time to build a more inclusive National Park System by designating and expanding new parks and monuments that preserve the nation’s rich and diverse history and contemplate the identity of America decades from now. The country’s increasing diversity and rapidly changing demographics are a reminder to never forget the nation’s rich history and to recognize how far American society has come. As the National Park Service has recognized, “Americans now and in the future deserve to see themselves—however they describe themselves—in the story of America. As we learn about the contributions of fellow Americans, we learn to appreciate and value our diversity and each other.” Policymakers should strive to build a National Park System that fulfills these goals.

Nidhi Thakar is the Deputy Director of the Public Lands Project at the Center for American Progress. Claire Moser is a Research and Advocacy Associate at the Center. Laura E. Durso is Director of the LGBT Research and Communications Project at the Center.

The authors would like to thank Matt Lee-Ashley, Senior Fellow and Director of the Public Lands Project; Hannah Hussey, Research Associate for the LGBT Research and Communications Project; Jamal Hagler, Special Assistant to Progress 2050; Spencer Perry and Julian Glover, interns with the LGBT team; and interns Annie Wang, Emily Ludwigsen, and Preeth Srinivasaraghavan.