Resolutions passed by town councils usually do not make headlines in Washington’s formidable news cycle. But on January 19, 2016, the town of Kure Beach, North Carolina, punched well above its political weight when it voted unanimously to become the 100th municipality between New Jersey and Florida to officially oppose offshore oil development along the Atlantic coast. These cities and towns—along with scores of regional chambers of commerce, trade groups, editorial boards, and a raft of Republican and Democratic members of Congress—have rightly concluded that an offshore oil industry in the Atlantic Ocean is simply incompatible with the economic and cultural bedrock of their communities: productive fisheries, good ocean water quality, and clean beaches.

These coastal stakeholders have made their voices heard at a critical time: The U.S. Department of the Interior, or DOI, is just weeks away from releasing its proposed offshore oil and gas development plan for 2017 through 2022—referred to as DOI’s five-year program. President Barack Obama’s administration will then reveal whether it intends to move ahead with oil and gas lease sales in the Atlantic.

Big Oil’s push for a new offshore frontier

Beginning more than two years ago, the governors of Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina—encouraged and aided by intense and often opaque lobbying by the petroleum industry—began a vociferous campaign in support of offshore oil and gas drilling in federal waters off the South and Mid-Atlantic coasts, promoting drilling as a fiscal and economic panacea. Their recent efforts paid off: Because the statute governing offshore drilling in federal waters—the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act—requires the secretary of the interior to consider the opinions of governors of “affected coastal State[s],” DOI included Atlantic lease sales in its preliminary proposal for the five-year program, which was published last year.

Leases for Atlantic drilling rights have not been sold since the early 1980s, when then-Interior Secretary James Watt gained notoriety for his broadly controversial—and ultimately futile—goal of opening up one billion U.S. offshore acres to oil and gas development. Yet the three governors’ vision for drilling in the Atlantic Ocean and reaping a windfall fails to recognize the concept’s significant economic and political problems.

The deeply flawed case for Atlantic Outer Continental Shelf development

First, it turns out that the Mid-Atlantic region’s coastal voters and their elected representatives do not want to put their coastal economy, fishing grounds, and world-class beaches at risk for an uncertain reward. As evidenced by resolutions from the political leaders of Kure Beach, along with those of Charleston, South Carolina; Savannah, Georgia; and many others, opposition to an Atlantic oil industry runs much deeper than Govs. Pat McCrory (R-NC), Nikki Haley (R-SC), and Terry McAuliffe (D-VA) anticipated.

Second, it is clearer than ever that oil and gas are the wrong energy sources to pursue along the Atlantic coast. Not only does offshore hydrocarbon development jeopardize recreation, tourism, wildlife, and fisheries—from the explosive underwater blasting of seismic surveying to the inevitable leaks and spills that accompany production—but independent analysis shows that drilling is far from the economic cure-all that Big Oil’s advocates have made it out to be. In a January 2015 report, Oceana compared a conservative estimate of developable Atlantic coast offshore wind resources with the oil industry’s own estimates for economically recoverable oil and gas reserves in the same area and found that offshore wind would generate substantially more energy and employment over the same 20-year time horizon, without the risks to water quality and coastal communities.

And last month, the Center for the Blue Economy in Monterey, California, analyzed the assumptions that underpin the oil industry’s primary claims of Atlantic drilling’s economic benefits and discovered a multitude of faulty assumptions. The report that the organization analyzed—written by the American Petroleum Institute and the National Ocean Industries Association—included unrealistic start dates for production and output estimates that were predicated on drilling in an area vastly greater than the one the Obama administration is currently considering. The industry’s assumed drilling area included waters off the coasts of Florida and New England, as well as waters well within the 50-mile buffer zone that the Obama administration established should any Atlantic development go forward. In addition, the Southern Environmental Law Center pointed out that the industry report based its projected economic benefits on oil selling for $120 or more per barrel—a far cry from the less than $30 per barrel prices producers earned in January 2016.

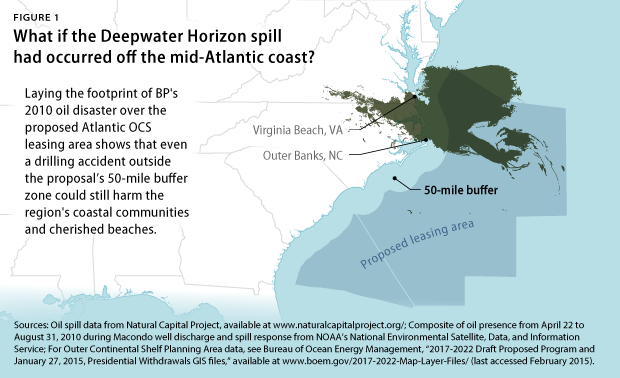

Meanwhile, the potential benefits of offshore oil development cannot be considered fairly in the absence of its potential costs. Although the industry report promised billions of dollars in new economic activity from an Atlantic offshore oil industry, the cumulative economic toll exacted by BP’s calamitous Deepwater Horizon blowout reached a staggering $53.8 billion by July 2015. As certainly as the offshore oil industry can create wealth for some, it can also destroy economic value for many other coastal stakeholders.

Outer Continental Shelf revenue sharing: An unfair proposition

A third flaw in the case is the pro-drilling governors’ assumption that new lease sales in Atlantic federal waters will be accompanied by the passage of the legislation required to divert resulting federal revenues from the U.S. Department of the Treasury to their states’ coffers. Even North Carolina Gov. McCrory noted this big asterisk next to his outspoken support for offshore drilling, saying in April 2015 that before his state moves forward with offshore drilling, “we need a clear commitment from the federal government on revenue sharing.” In other words, Gov. McCrory and other drilling supporters want the federal government to plan, permit, and oversee the risky extraction of Atlantic oil reserves owned by the American public as long as the U.S. Congress provides a special rule change granting their states a big portion of the profits.

When Sens. Lisa Murkowksi (R-AK) and Mary Landrieu (D-LA) attempted to pass such a revenue sharing bill for Alaska and the Gulf Coast states in 2013, a Center for American Progress analysis highlighted the high cost and fundamental unfairness of such deals. Resources from federal offshore lands—such as subsea oil and gas in the Atlantic Ocean—belong to all Americans, who, by law, foot the bill for their management and are entitled to a portion of the proceeds from their extraction and sale. By siphoning these returns to select pro-drilling states, revenue sharing deals increase the burden on U.S. taxpayers, worsen the federal deficit, and penalize neighboring coastal states that opt out of offshore drilling but remain exposed to its risks. Accordingly, the budgetary watchdog group Taxpayers for Common Sense labeled the Murkowski-Landrieu bill “Bad Fiscal Policy,” and the bill never advanced beyond committee. There is little evidence that Congress would view an Atlantic coast version of such a deal with any greater favor.

Bipartisan support for sound policy: Letting go of Atlantic exploration and drilling

A hackneyed narrative on the politics of offshore drilling pits “drill, baby, drill” Republicans against climate hawk Democrats. Yet as the groundswell of opposition to Atlantic drilling rises throughout the purple and red states of the Mid-Atlantic region, it has become clear that in this case, the choice is simply between sound and unsound natural resources policy—no political affiliation required.

Kure Beach’s resolution aligned it with both the Mid-Atlantic and South Atlantic Fishery Management Councils, politically diverse commissions that each issued strong statements of concern about the impacts of oil development on the fishing industry—from seismic surveying to catastrophic blowouts such as the Deepwater Horizon disaster. And perhaps most strikingly, the North Carolina town joined a distinctly bipartisan bloc of 8 Republican and 23 Democratic members of the U.S. House of Representatives from across the Mid-Atlantic, who are now standing together to protect their coast. In a formal letter sent to DOI’s Bureau of Ocean Energy Management Director Abigail Hopper in December 2015, this extraordinary coalition called for a halt to the current permitting process for new offshore oil and gas exploration, writing:

Along the Atlantic coast, nearly 1.4 million jobs and more than $95 billion in GDP rely on healthy ocean ecosystems, mainly through fishing, tourism, and recreation. Seismic testing and oil drilling will put the coastal economy and way of life at risk.

This makes the Obama administration’s upcoming decision on whether to include an Atlantic lease sale in the 2017–2022 five-year program a straightforward one: Leave it out and let it go.

Shiva Polefka is a Policy Analyst for the Ocean Policy program at the Center for American Progress.