Grim news on climate change continues to flow from the Arctic like a river from a melting glacier: Shrinking sea ice; rising sea levels; higher and more damaging storm surges; thawing permafrost; imperiled communities; and raging wildfires have all made headlines this year.

When Secretary of State John Kerry convenes foreign ministers from Arctic nations and other countries in Anchorage, Alaska, on August 30 and 31 to discuss the Arctic, his top priority should be reaching an agreement on how to mitigate the threats of climate change in the region. President Barack Obama is scheduled to attend the conference, and with good reason: Climate-driven events in the Arctic have serious security implications for the United States and potentially catastrophic geopolitical consequences.

Secretary Kerry and the foreign ministers should seek to leave Anchorage with a joint declaration that includes two concrete items:

- A pact to lock in a strong global climate agreement at the U.N. climate talks in Paris this December

- A pledge to immediately cut black carbon and methane pollution to curb Arctic and global warming

Secretary Kerry and President Obama already plan to use the Conference on Global Leadership in the Arctic: Cooperation, Innovation, Engagement and Resilience, or GLACIER, to elevate awareness of the consequences of unchecked climate change, discuss strategies to slash carbon dioxide emissions and black carbon pollution, and advance ideas for strengthening Arctic community resilience. The conference comes just four months after Secretary Kerry became Arctic Council chairman—a two-year position that rotates among the eight Arctic nations.

Challenges facing the Arctic

The near-Arctic choice of location for this important discussion about climate change was no accident. The Arctic is warming twice as fast as the rest of the planet. Rapidly receding sea ice is opening up the Arctic to risky commercial activity—including more shipping traffic and oil and gas exploration—as well as shrinking the buffer that shields Native Alaskan coastal villages from storm surges.

Shorter sea ice seasons have made it more difficult for polar bears, walruses, and other wildlife to hunt, threatening the survival of many animals and throwing the Arctic ecosystem far out of balance. Sea ice has dwindled to the lowest maximum extent in recorded history, forcing National Geographic to literally redraw the Arctic Ocean in the latest edition of its Atlas of the World.

The global impacts of the melting Greenland ice sheet and Arctic glaciers include rising sea levels. The Polar Research Board of the National Research Council has linked the melting Arctic to wholesale changes in the “winds, temperatures and precipitation patterns around the globe, with potentially strong local effects along the east coast of the United States and west coast of northern European countries.” In particular, these changes may be influencing the frequency, location, and severity of storms—think Hurricane Katrina and Superstorm Sandy—as well as the polar vortex weather events that have punished the United States’ East Coast and Midwest during recent winters.

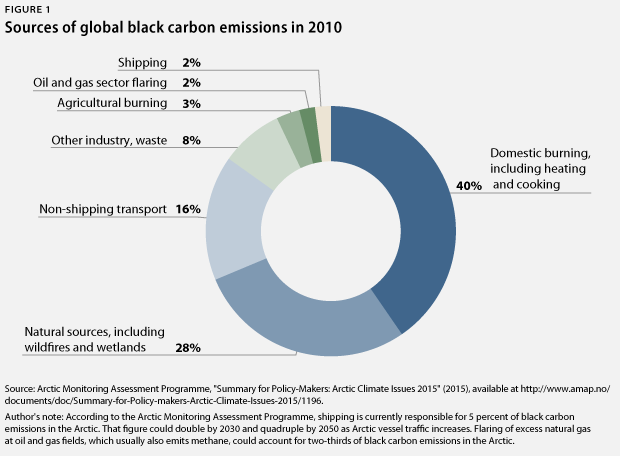

While emissions of CO2 are the primary driver of global climate change, short-lived climate pollutants such as black carbon—or soot—and methane threaten public health and accelerate warming in the Arctic and around the globe. Diesel cars and trucks; woodstoves; wildfires and agricultural burning; oil and gas production; and shipping all emit black carbon, a pollution that is often most potent near its emission source. Black carbon emissions are linked to heart attacks, strokes, respiratory illness, cancer, higher rates of infant mortality, and premature death.

The Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change have concluded that, when deposited on highly reflective surfaces such as ice and snow, black carbon causes surface warming and melting by absorbing solar radiation and reducing the ability of the surface to reflect sunlight. These effects make the Arctic highly susceptible to additional warming due to black carbon pollution.

Secure a strong global climate deal in Paris

Momentum appears to be building for an international pact to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Slashing global greenhouse gas emissions will not only slow overall global warming but will also reduce Arctic warming. In recent months, 28 nations—including the United States, China, Norway, Mexico, Japan, and South Korea—plus the 28 members of the European Union have announced emission reduction goals. In August, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, or EPA, unveiled the final version of its Clean Power Plan, which calls for a 32 percent cut in CO2 emissions from 2005 levels by 2030. The plan is a core aspect of President Obama’s larger strategy to cut overall U.S. greenhouse gas emissions 26 percent to 28 percent compared with 2005 levels by 2025.

World leaders have expressed confidence that they will reach a climate deal in Paris. But many, including Secretary Kerry, have openly lamented that this year’s emission reduction pledges will not be strong enough to limit global warming to 2 degrees Celsius—the long-term goal of the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change and the level scientists have identified as the threshold for preventing unmanageable climate changes.

In Anchorage, world leaders must deliver an urgent call for countries to make deeper emissions cuts both now and in the future by accelerating the shift to clean energy sources such as wind and solar. Later this year in Paris, participants should also agree to a legally binding and transparent process for countries to regularly set more ambitious national emission reduction goals. Such a process will be essential to avoiding dangerous levels of global and Arctic warming.

Cut black carbon and methane pollution

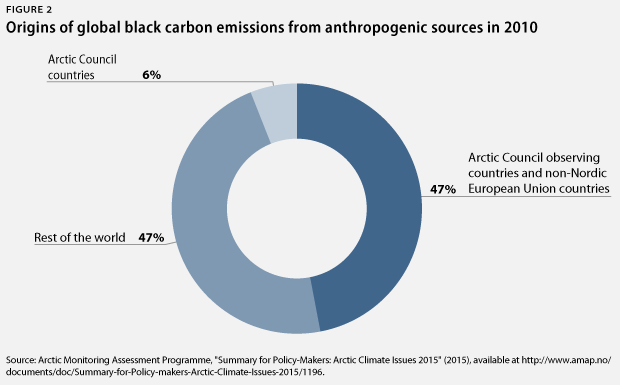

The eight Arctic nations—Canada, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden, the United States, and Denmark, including Greenland and the Faroe Islands—are responsible for roughly one-third of the recent Arctic warming directly attributed to black carbon. The rest of the Arctic warming due to black carbon comes from pollution that originates outside the Arctic, highlighting the need for global action to cut black carbon emissions.

If world leaders take full advantage of the available opportunities to cut black carbon, methane, and ozone pollution globally, they can reduce Arctic warming by roughly half of a degree Celsius by 2050. Together with steep reductions of global CO2 and other greenhouse gas emissions, limiting short-lived climate pollutants could help keep global warming below 2 degrees Celsius. Such action is urgent, particularly in the Arctic: As sea ice continues to melt, oil and gas development is likely to increase, bringing even more black carbon pollution to the region.

This summer and fall, the United States has the opportunity to take concrete actions to cut its black carbon and methane pollution and to leverage similar actions from other countries. For example, Department of the Interior Secretary Sally Jewell should announce that the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, or BOEM, will update its air quality standards for offshore oil and gas development to reduce black carbon emissions and other pollutants. Updated standards that are at least as stringent as the EPA’s air quality standards and address black carbon pollution would protect public health and the environment, particularly in areas with snow and ice such as the Arctic.

Industry experts acknowledge that black carbon could be reduced without hurting the economy. In an email to the author, Joe Kubsh, executive director of the Manufacturers of Emission Controls Association, said that “diesel particulate filters are a proven cost effective technology for reducing black carbon emissions from diesel engines by up to 99% when paired with the use of ultra-low sulfur diesel fuel, including for offshore oil and gas production activities.” If BOEM gathers expert and public comments on the effects of black carbon on public health and the environment and cost-effective control technologies, as seven senators requested in a recent letter to Secretary Jewell, the Department of the Interior likely will have the evidence it needs to include black carbon controls in the final rule.

In Anchorage, Secretary Kerry should pledge, along with other world leaders, to take immediate steps to reduce black carbon and methane emissions. The EPA made a move in this direction with its proposed new methane standard for oil and gas facilities. By committing to new actions to cut black carbon and methane pollution, world leaders can build momentum to secure a strong global climate agreement in Paris. New commitments in Anchorage also would accelerate implementation of the Arctic Council’s “Framework for Action: Enhanced Black Carbon and Methane Emission Reductions,” which calls on Arctic nations to complete black carbon and methane emissions inventories and action plans and invites Arctic Council observer nations to do the same.

Conclusion

Arctic and global warming are leading the world closer to rapidly approaching tipping points that will narrow cost-effective climate solutions, adding to an expanding list of regrets. In Anchorage, world leaders can reverse these trends by making a commitment to secure a strong global climate agreement in Paris and by pledging to immediately cut black carbon and methane pollution. The time to act is now.

Cathleen Kelly is a Senior Fellow at the Center for American Progress.

The author would like to thank Greg Dotson, Gwynne Taraska, Ben Bovarnick, Meredith Lukow, Meghan Miller, and Kyle Schnoebelen for their contributions.

The Center for American Progress thanks the Nordic Council of Ministers for its support of our education programs and contribution to this column. The views and opinions expressed in this column are those of the author and the Center for American Progress and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Nordic Council of Ministers. The Center for American Progress produces independent research and policy ideas driven by solutions that we believe will create a more equitable and just world.