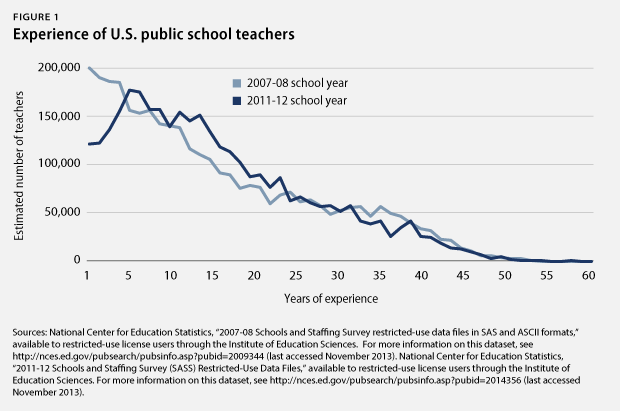

Five years ago, U.S. teachers were asked in a survey how many years of experience they had; their most common answer was one year. Policymakers feared an impending crisis because, if past trends held, about half of these teachers would leave in their first five years. But the latest results from the Schools and Staffing Survey, or SASS—a nationally representative study of teachers by the U.S. Department of Education released just weeks ago—show that 70 percent of teachers in their first year stayed in the profession. In the new SASS, most teachers said that they had taught for five years. (see Figure 1) These new survey results reveal that the teacher retention concerns were unfounded. Since most new teachers stayed in the profession, it’s time to turn attention to these mid-career teachers to ensure policies support their professional growth.

One could imagine all sorts of potential reasons why these novice teachers stayed in the profession. The economy was deeply uncertain during this time period. The Great Recession started in 2009, and the resulting financial uncertainly may have kept more teachers in the teaching profession. The latest survey evidence suggests that this dynamic may have largely not played out: About the same proportion of teachers agreed—before and after 2009—with the statement that “If I could get a higher paying job, I’d leave teaching as soon as possible.”[1] With many experienced teachers retiring over the past few years, these beginning teachers may have stayed longer because they expected more opportunities to take on more professional responsibilities.[2]

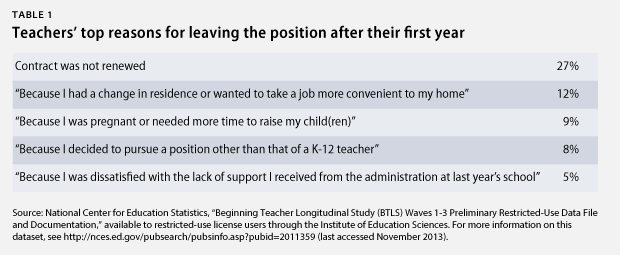

Researchers will be looking at this data for years to come, but for now, one thing is clear: This time period also saw one of the most dramatic changes in education policy agendas this nation has ever seen. States and districts have been challenged to rapidly revamp outdated teacher evaluation policies through Race to the Top competitions and No Child Left Behind waivers. These federal programs have sparked reforms that have begun to dramatically reshape the work of classroom teaching. As these reforms began to take shape, teachers in states and districts across the country have encountered growing demands. Yet as the reforms started to roll out, teachers stayed in the profession. In fact, 87 percent of the first-year teachers from 2007 to 2008 stayed through their third year. And that percentage could have been higher. The most common reason teachers left the profession after their first or second year was mostly out of their control: their contract wasn’t renewed. (see Table 1)

These data are far from conclusive, however, since there are a number of other reasons why this could have occurred. But the new research should give pause to critics who have argued that the education reform initiatives under President Barack Obama and Secretary of Education Arne Duncan would lead teachers to bristle under the new evaluation systems and leave the profession. Some claimed that teachers would react strongly to teacher evaluations that are based in part on student test-score growth and that the stress would drive many of them out. Bob Sullo, an education consultant and author, called it a “recipe for disaster.” And education historian Diane Ravitch predicted that “many will leave teaching, discouraged by the loss of their professional autonomy.”

In contrast, over the course of President Obama’s first term, about two-thirds of teachers were as likely to agree that if they “could go back to college and start over again,” they would “probably” or “definitely” still become teachers.

But enacting reforms with the promise of improving learning for all children and keeping new teachers in the profession is just the start of the work. The other, and arguably more important task, is ensuring that they continue to grow in effectiveness and become expert, master teachers.

Research shows that teachers often reach their peak effectiveness after five years in the profession. Teachers improve a great deal each year during their first several years, but after their fifth year, teachers generally hit a plateau of effectiveness with comparatively lower growth in teaching expertise in additional years. Therefore, if teachers continue to stay in the profession, it is imperative that their instruction improves throughout their careers in order to raise the quality of teaching and learning for students.

Teacher evaluation is a good place to start. Fortunately, education leaders in states and districts across the United States are working to perfect teacher evaluation systems so that they become support systems that highlight teachers’ strengths and identify ways to work on their weaknesses. And teachers in states that are further along in the process of rolling out teacher evaluation view these systems positively. In Tennessee, for example, teachers are increasingly seeing the evaluation process as a tool for improving teaching and learning with more than half of teachers who responded to a recent survey reporting that teacher evaluation will improve teaching in their schools.

The key to a successful teacher evaluation system is ensuring that it is used as a support mechanism for the improvement of teaching. For this, targeted professional development for teachers is invaluable. Unfortunately, many states and districts are not providing the type of professional development that will have the largest impact on teachers’ instruction. Research shows that for professional development to have a chance at boosting student achievement, it must happen over an extended period of time in high-value forms such as coaching or collaboration that are aligned with the goals for teaching and learning. Instead, too much of the professional development that teachers receive is not aligned with their individual needs and happens in one-shot workshops or conferences. Pairing teacher evaluation with individualized professional development opportunities could help bridge the gap between teacher evaluation, teacher support, and student achievement.

During this time of immense reform that directly impacts teachers’ daily work lives, it’s also important that leadership in states, districts, and schools utilize teachers’ expertise. For this, it would be wise for states and districts to create career ladders that empower teachers to take on leadership roles, enabling them to actively participate in the changes happening in their schools while staying in the classroom. Differentiated compensation systems that reward teachers for their additional responsibilities and expertise are natural extensions of such systems.

Since data show that new reforms won’t deplete the profession of new educators, it’s time to turn new reform policies into powerful systems to support these early career teachers to become world-class experts in helping all students learn. These new reforms, once the target of criticism from those opposed to them, may turn out to be systems that encourage new teachers to stay and help them realize their potential as expert practitioners in our nation’s classrooms.

Kaitlin Pennington is a Policy Analyst on the Education Policy team at American Progress. Robert Hanna is a Senior Education Policy Analyst at the Center.

Endnotes

[1] In the 2007-08 school year, 25 percent of teachers agreed with this statement. In the 2011-12 school year, 30 percent of teachers agreed with the statement.