President Donald Trump offered one major K-12 education proposal during the presidential campaign: a $20 billion plan that would reprioritize existing federal education funds to provide vouchers for private-school choice. And with his selection of Betsy DeVos as secretary of education, who has been referred to as the “four-star general of the pro-voucher movement,” he signaled the seriousness with which he intends to pursue this idea as a solution to what Trump has called “failing government schools” and DeVos has called a “dead end” public education system.

Much has been written about the devastating impact such a proposal would have on local communities, since $20 billion would subsume most federal K-12 education spending. Currently, that spending is specifically targeted to low-income students, students with disabilities, English language learners, and other vulnerable children. But little has been written about the fact that the proposal misses the mark when it comes to the real challenges facing the vast majority of school districts across the country. The simple fact is that most rural and suburban areas are either sparsely populated or organized in small districts where there are not enough schools for vouchers to be a viable or effective policy solution. In these districts, vouchers would be not just ineffective, but they could also dramatically destabilize public school systems and communities.

Underscoring this point is the fact that Republican Sens. Lisa Murkowski (AK), Susan Collins (ME), and Mike Enzi (WY) all used their limited time for questions during DeVos’ confirmation hearing to speak about the special challenges facing rural and frontier schools in their states.

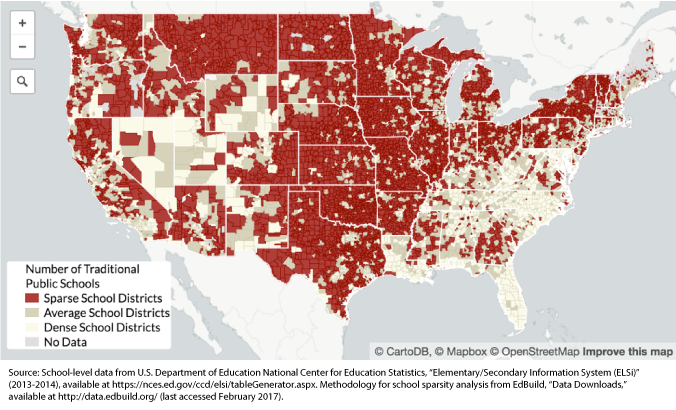

In order to examine the viability of vouchers throughout the nation, the Center for American Progress used data and visuals published by EdBuild, a national nonprofit focused on improving the way states fund public schools. The organization mapped data from the National Center for Education Statistics to visualize the density and diversity of America’s school districts. The goal was to get a handle on the number of schools in districts of varying size across the country and the locations of those districts. The interactive map allows users to see where districts are that fit into the following categories:

- Sparse districts: a unified school district with four or fewer schools, an elementary-school-only district with three or fewer schools, or a secondary-school-only district with two or fewer schools

- Average districts: a unified school district with five to eight schools, an elementary-school-only district with four to five schools, or a secondary-school-only district with three to five schools

- Dense districts: a unified school district with nine or more schools, an elementary-school-only district with six or more schools, or a secondary-school-only district with six or more schools

Click here to view the full interactive map.

Click here to view the full interactive map.

The findings underscore the severe limitations of President Trump and Secretary DeVos’ one-size-fits-all vision of nationalizing private-school vouchers. Public education in America is far from one-size-fits-all, and there is dramatic diversity within the more than 13,000 school districts across the nation—from the 1 million students in New York City’s more than 1,500 public schools, to the 60 students at the K-8 school on Beals Island, Maine, and its 100-student high school shared with the nearby town of Jonesport. Diversity can also be found among the 67 countywide districts in Florida educating more than 2.5 million students, the 545 districts in New Jersey educating nearly 1.3 million students, and the 413 districts educating fewer than 150,000 students in Montana.

When CAP staff members looked at the data, they found that there are:

- Nearly 9,000 sparse school districts that have four or fewer schools where voucher proposals are highly unlikely to work and could decimate the public system

- Another 2,200 average school districts that have five to eight schools where vouchers may not work and risk harming existing schools’ ability to serve millions of students

After excluding charter schools and regional agencies that are legally considered school districts, this means that 85 percent of the 11,200 regular school districts fall into these two categories of sparse and average districts where vouchers are entirely or more than likely to be unworkable as a logistical matter.

Impact of vouchers on sparse districts and rural communities: The Wyoming example

Sparse districts are districts that have four or fewer schools in the entire district, with two elementary schools, one middle school, and one high school as a typical configuration. Hot Springs County School District #1 in Thermopolis, Wyoming, for example, has a total of 650 students attending the district’s one elementary school, one middle school, and one high school. It is the only school district in Hot Springs County, Wyoming, with the closest school located in another district more than 30 miles away. It serves the county of Hot Springs, which covers more than 2,000 square miles. There are no general education private schools or charter schools in the county, and the state of Wyoming does not have a voucher program.

The precise impact of a voucher program on communities such as Hot Springs County will not be known until a legislative proposal is delivered. However, what is certain is there are multiple ways in which the public schools could be adversely affected.

If a state such as Wyoming, which currently does not have a voucher program, were to establish one as a result of a Trump-DeVos plan, private schools might open or expand to take advantage of the new funding source. If this were to occur, the public school system could see decreases in enrollment and per-pupil funding.

Changes in enrollment are especially challenging for communities that have no opportunity to adjust their portfolio of schools. Even if just a handful of students utilized the vouchers, a district such as Hot Springs County—which covers a wide geographic area with one school in each grade span—would face difficult decisions such as reducing classes and course offerings, cutting activities, or reducing student supports to compensate for the reduced funding when students leave.

There is also no reason to believe the new schools that crop up in response to the voucher initiative would be higher performing than the schools that are in operation today. Once researchers account for demographics, students in public schools actually outperform students in private schools, according to a large-scale 2014 study of National Assessment of Educational Progress, or NAEP, data. And like most public schools in rural areas, these private schools would face significant challenges recruiting and retaining qualified teachers, providing differentiated and challenging content, providing support for students with special needs, and more. And if these new schools are competing with the existing public schools, they will dilute the resources available for each. The likely result would be a race to the bottom, with two sets of schools struggling to provide a high-quality education to children who badly need it.

When President Trump was on the campaign trail and announced his proposal to provide a block grant for vouchers, he said that the funding distribution would “favor states that have private school choice.” This means that even if a state does not allow private school vouchers, it could lose funding if formulas shift funding toward states that do.

Under the best-case scenario, a new federal voucher program would have no impact on the community: It would not lose funding to other districts or states, nor would it lose students to other schools. Under that scenario, while not doing harm, it would nonetheless fail to address the real challenges that rural schools face, including low teacher compensation, limited ability to offer advanced coursework, a lack of extracurricular and enrichment activities, low college-going rates, and more.

If President Trump’s proposal becomes reality, the most likely outcome is that Wyoming—which, as stated above, does not currently have a voucher program—will not establish one, since doing so would be tangential to the challenges facing its students. And if that were to be the case, the state’s schools would likely lose money, as the Trump voucher proposal favors states that set up these programs.

Impact of vouchers on suburban communities

Even in suburban areas, vouchers could destabilize public schools. In the largely suburban state of New Jersey, 70 percent of the districts are labeled sparse and 19 percent are labeled average in the map above. In Connecticut, which has significant suburban areas bordering New York City and small towns in the western part of the state, 82 percent of school districts are sparse or average. Average-sized districts have five to eight schools, a district composition that could include five elementary schools, two middle schools, and one high school or some variation on that distribution.

Even in average districts, if just 30 students leave with vouchers, the ramifications for the public schools could be significant. At the average annual per-pupil expenditure of approximately $11,800, 30 fewer students could mean an annual loss of just more than $350,000, enough to pay six teachers’ salaries. Moreover, if enrollment losses were spread across schools, district costs such as building maintenance and utilities would remain fixed. Under such circumstances, district administrators would in all likelihood be forced to make up for the lost revenue through combinations such as reducing the number of teachers and cutting supplies and supplemental programming. And because staff salaries and benefits make up an average of 80 percent of school budgets, it is likely that district leadership would need to cut staff spending to accommodate shrinking budgets. That would likely mean some combination of downward pressure on teacher salaries, larger classes, and limited advanced and elective course offerings.

Even in communities with average-sized school districts, where implementing a voucher program would be easier than in sparse districts, there are still significant barriers to implementing voucher programs that warrant further research, including logistical challenges. For example, most parents are unable or unwilling to drive long distances to get their children to schools outside their neighborhoods. More research is needed to examine the distance between schools and people’s homes within specific geographic areas in order to better understand the viability of vouchers in the rural and suburban areas that make up the majority of the country.

Impact of vouchers on urban communities

Even if communities can respond to school choice policies or other fluctuations in enrollment by adjusting their portfolio of schools, these decisions are not to be taken lightly. The decision to close a school is frequently met with fierce resistance from the community, as closings have big impacts on neighborhoods where school buildings are important community resources and sources of neighborhood stability; where public schools are significant employers; and where distances to other schools can be substantial.

Urban schools have high concentrations of students living in poverty and students who are English language learners. These students will be made even more vulnerable through an approach that incentivizes them to go to private schools. Private schools have wide latitude to cherry-pick their student populations through admissions and discipline decisions, and often lack the ability to provide specialized special education services. Some state voucher programs for students with disabilities even require families to sign away their rights when they attend private schools. As a result, students with the greatest challenges and needs are likely to remain in public schools, even as districts lose funds to private schools that serve less-needy students.

Transportation may also be a problem in many urban areas. Even if schools are near one another geographically, if there is not reliable public transportation to take students to and from schools efficiently, going even one mile further to get to school can be a deal breaker, particularly for a single working parent.

Finally, real estate is expensive and hard to come by in many urban areas, making it difficult for existing schools to expand or new schools to open. Good private schools are often oversubscribed and unlikely to be able to accommodate significant numbers of students from the public system.

In short, vouchers can have detrimental effects on communities and limit high-quality options for students even in areas with an abundance of schools in close proximity to one another.

Benefits of school choice

While private-school choice carries significant risks for students, public-school choice is not a bad thing to be avoided at all costs. Charter schools have created high-performing options for millions of families across the country, and initiatives such as New York City’s small high schools of choice have shown that public-school choice in large districts can significantly improve graduation rates.

The largest nationwide study of charter performance from Stanford University’s Center for Research on Education Outcomes found particularly strong outcomes for low-income black and Hispanic students and that recent improvements in charter performance are “mainly driven by opening higher-performing schools and by closing those that underperform.” New York City pursued a policy in 2002 that “closed many large, comprehensive high schools with a history of low performance” and opening hundreds of small secondary schools of choice. This was not without controversy, but research has shown that the program “markedly increased high school graduation rates for large numbers of disadvantaged students of color” as more students earned the rigorous Regents diploma.

Conclusion

The Trump-DeVos plan for privatizing the nation’s schools is not a workable solution in vast swaths of the country. Under the best-case scenario, this one-size-fits-all reform will have no impact on these schools. Under the worst-case scenario, it will direct funds away from public school systems, either through a new formula that advantages states that establish voucher programs or by draining students and their accompanying per-pupil allocation away from public schools. The result will be overcrowded classrooms; even more poorly paid teachers and school staff; and fewer resources for enrichment activities, school facilities, and more.

As secretary of education, DeVos is responsible for meeting the department’s mission to “[s]trengthen the Federal commitment to assuring access to equal educational opportunity for every individual.” We hope Secretary DeVos recognizes that our nation’s public schools are far from one-size-fits-all—and that the solutions and reforms needed to improve them should not be either.

Secretary DeVos alluded to the need for different solutions in different contexts when she stated during the opening remarks of her Senate confirmation hearing, “Parents no longer believe that a one-size-fits-all model of learning meets the needs of every child.” CAP agrees with that sentiment but finds it much harder to believe that private-school vouchers, the issue she focused on in the hearing and throughout her career, are the one-size-fits-all solution that will actually meet the needs of students.

Note: See this chart for an example of the difference between strong policies for public charter schools and President Trump and Secretary DeVos’ voucher proposal.

Neil Campbell is the Director of Innovation for the K-12 Education Policy team at the Center for American Progress. Catherine Brown is the Vice President of Education Policy at the Center.