Download the memo (pdf)

Download to mobile devices and e-readers from Scribd

A key issue in the upcoming debate over housing finance reform will be the importance of the 30-year fixed-rate mortgage, the pillar of the modern U.S. housing finance system. Many conservatives argue for a withdrawal of all government support from the mortgage finance system. One nearly certain outcome of this course of action would be the elimination of the 30-year fixed-rate loan as a mortgage financing option for the vast majority of Americans.

Consequently, conservatives have begun a campaign to convince Americans that other mortgage products, with shorter durations or adjustable rates, are superior to the 30-year fixed-rate mortgage. Why? Because they believe that if they can undermine the broad popularity of this type of loan, they can advance their goal of removing government support for the mortgage markets.

There are three major arguments in favor of continuing to emphasize the 30-year fixed-rate loan in the United States.

- First, the 30-year fixed-rate mortgage provides cost certainty to borrowers, which means they default far less on these loans than for other products, particularly during periods of high interest rate volatility.

- Second, the 30-year fixed-rate mortgage leads to greater stability in the financial markets because it places the interest rate risk with more sophisticated financial institutions and investors who can plan for and hedge against interest rate fluctuations, rather than with unsophisticated households who have no such capacity to deal with this risk and who are already saddled with an enormous amount of financial burden and economic uncertainty.

- Third, the 30-year fixed-rate mortgage leads to greater stability in the economy because short-term mortgages are much more sensitive to interest rate fluctuations and thus much more likely to trigger a bubble-bust cycle in the housing markets. Indeed, there may be reason to believe that a primary cause of the recent housing bubble-and-bust cycle was the rapid growth of short-duration mortgages during the 2000s, which caused U.S. home prices to become more sensitive to the low interest rate environment created by Alan Greenspan’s Federal Reserve.

It is also important to recognize that even if we completely eliminated the 30-year fixed-rate mortgage from the American housing markets, we would still need a significant government role to ensure a broad and stable mortgage market, as I explained two weeks ago. It is inconceivable that a “purely private” mortgage system could meet the enormous mortgage liquidity needs of U.S. housing. Such a system would also be extremely unstable, prone to extreme bubble-bust cycles in the housing markets of the sort we just witnessed, every 5-to-10 years. There is a reason that every advanced economy in the world provides significant governmental support (either explicitly or implicitly) to its mortgage markets.

Critics of the U.S. 30-year fixed-rate mortgage also ignore the historically anomalous period we recently experienced up until the housing bubble began to burst in 2007. Since the early 1980s, interest rates have been declining steadily, and up through 2007, home price appreciation was generally on an upward trajectory. This constituted the perfect environment for short-duration mortgages as the high levels of interest rate risk and refinancing risk these types of loans pose to borrowers were nullified by declining rates and a large array of options to refinance or sell the home.

Indeed, when home prices began to fall in 2007, the high risks associated with short-term mortgages became evident as defaults for these loans soared. Just as many Americans in 2007 seemed to believe that housing prices would always rise, based on recent history, many American policymakers today seem to believe that interest rates will always be low and stable and that mortgage refinancing options will always be plentiful, based on recent history. Inevitably, however, interest rate risk and liquidity risk will once again rear their ugly heads, exposing the problems with shorter-duration mortgages. Should the United States transition to shorter-term mortgages permanently, the economy would be far more vulnerable to interest rate or liquidity shocks.

Finally, as we saw in the past decade, a rapid shift to new types of mortgage products can confuse consumers and lenders alike, resulting in choices that are not necessarily in their best interests. Americans know and are used to the 30-year fixed-rate mortgage, which has been a mainstay for prospective homebuyers for many decades. And the evidence is pretty clear that American consumers know how to shop for 30-year fixed-rate mortgages and lenders know how to price the American 30-year fixed-rate mortgage. A radical transition to a mortgage system that emphasizes shorter-term loans would likely result in some significant costs as consumers and lenders experienced growing pains in adapting to the new system.

So let’s look at all of these facts in more detail so that Americans will understand why eliminating the 30-year fixed-rate mortgage as our primary mortgage option would be a disaster for homeowners and the broader economy, both now and in the future.

Background on home mortgages and the recent housing crisis

To state the obvious, mortgage lending requires an enormous amount of capital. The U.S. residential housing market currently has some $10.3 trillion in total mortgage debt outstanding. Moreover, mortgage lending requires capital to be committed for a very long period of time.

The typical mortgage, both in the United States and in other developed countries, is designed to be fully repaid, or amortized, over a very long timeframe, often 25 or 30 years. This long repayment period allows working households to afford their mortgage payments while matching the expected life of the purchased home, which typically lasts for many decades.

While virtually all mortgages today are amortized over a long period, the U.S. 30-year fixed-rate mortgage is unique, insofar as it locks in a single mortgage rate for borrowers for the entire 30-year amortization period of the loan. There are basically two primary alternatives to the U.S. 30-year fixed-rate mortgage, both of which use a 25-to-30-year amortization schedule. Adjustable-rate mortgages, or ARMs, offer a fixed interest rate for a short period of time, typically two years to seven years (this initial rate is often called a “teaser rate”), after which the interest rate “resets” to a market-based level. This is the type of loan we saw proliferate during the recent mortgage bubble.

Alternatively, short-term fixed-rate mortgages (often called “bullet” loans) offer a fixed interest rate for a short period of time (also typically two years to seven years), after which they must be refinanced or “rolled over.” This type of loan, which is mostly nonexistent in the United States, is the dominant type of mortgage in Canada.

The main difference between the 30-year fixed-rate mortgage and shorter-term loans is in interest rate risk

Some critics of the 30-year fixed-rate mortgage argue that the recent solid performance of mortgage markets in some countries where shorter-term loans are predominant—particularly Canada, which has a five-year bullet loan amortized over 25 years—provides evidence that the 30-year mortgage is not any more stable than the five-year product. This argument confuses the difference between interest rate risk and credit risk.

Interest rate risk is the risk that interest rates will experience sudden volatility, which can present financing difficulties to the lender and payment difficulties for the borrower, especially given the long amortization periods for mortgages. Credit risk is the risk that borrowers will stop paying their mortgages, perhaps due to a loss of wealth or income, perhaps due to an unforeseen illness, or perhaps due simply to bad behavior.

The primary difference between the U.S. 30-year fixed-rate mortgage and shorter-duration loans is who bears the interest rate risk. For the 30-year mortgage, the interest rate risk is borne by financial institutions or investors in mortgage-backed securities. Borrowers of the 30-year fixed-rate mortgage have cost certainty for the duration of the loan, which shields them against any sudden increases in their loan payments.

But for shorter-duration mortgages, interest rate risk is largely transferred to the borrower, who now has cost certainty for only a short period of time—until the loan rolls over or the “teaser rate” expires—after which he may face a payment shock if interest rates have risen significantly. Financial institutions and investors bear far less interest risk in this product.

The recent mortgage crisis was caused by credit risk, not interest rate risk

The recent mortgage crisis was not caused by interest rate risk but rather by poorly managed and underpriced credit risk. The wave of mortgage defaults that struck most of the developed economies of the world did not occur because of interest rate spikes but rather because credit was poorly underwritten by mortgage lenders and investors. Too many high-risk loans were originated and credit risk was poorly understood by the rating agencies.

Moreover, as I argued in a previous article, the relatively strong performance of the Canadian mortgage market is not tied to the predominance of the five-year mortgage in that country but is rather the result of continued strong regulatory oversight of their mortgage banking system. Canada, unlike our country, did not allow an unregulated “shadow banking system” to grow to capture 40 percent of the mortgage market during the height of the housing bubble.

The cost certainty of the 30-year fixed-rate mortgage insulates borrowers against interest rate and refinancing risks

One important reason why the 30-year fixed-rate mortgage is superior to other mortgages is that it provides cost certainty to borrowers. A U.S. household with a 30-year fixed-rate mortgage always knows what its mortgage payments will be. Because shorter-duration products are basically designed to be refinanced every two years to seven years, homeowners with these types of loans face significant risks that interest rates may rise, making their home payments unaffordable after that initial two-to-seven-year period expires.

In addition to this interest rate risk, shorter-term mortgages also expose borrowers to significant refinancing risk. As we saw during the recent credit crisis, borrowers who need refinancing may not always be able to find it, particularly during economic downturns, when home values are declining and banks are more reluctant to lend.

This is true even when interest rates are stable or declining. By forcing borrowers to refinance every two years to seven years, adjustable-rate and short-term mortgages expose borrowers not only to ordinary interest rate risk—the risk that mortgage finance might become more expensive as interest rates rise—but to two other refinancing risks.

First, there is the risk that the borrower’s home value has declined, forcing him to put up more equity or even precluding the possibility of financing altogether. Second, there is the risk that mortgage finance might be unavailable to the borrower because banks have pulled back their lending due to the cyclical nature of bank lending, such as we are now seeing.

The 30-year fixed-rate mortgage insulates borrowers against these risks since their payment streams are fixed, even if their home price has declined or there was a financial crisis that made banks unwilling to lend. If we transitioned to an economy where the 30-year fixed-rate mortgage was no longer the dominant mortgage product, Americans would face the risk of losing their home every time they refinanced, due to rising interest rates or an unavailability of refinancing options, even if they otherwise could have been able to make their payments.

The higher risks of short-term loans lead to consistently higher default rates, particularly during periods of housing market distress

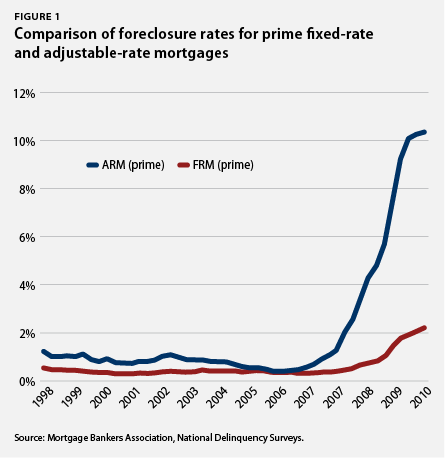

Because of its cost certainty and protections against interest rate and refinancing risk, default rates for the 30-year fixed-rate mortgage are markedly lower than those for shorter-duration loans, particularly during periods of interest rate volatility, home price declines, or mortgage illiquidity. As shown in the accompanying charts, the increased interest rate and refinancing risks of shorter-duration mortgages translate into a consistently higher rate of foreclosures for these products, as compared to long-term fixed-rate loans. Note that all of the loans described in these charts are prime loans, made to borrowers with similar credit characteristics, and so the differences in foreclosure rate are purely attributable to the differences between long-term fixed-rate loans and shorter-duration loans.

Because of its cost certainty and protections against interest rate and refinancing risk, default rates for the 30-year fixed-rate mortgage are markedly lower than those for shorter-duration loans, particularly during periods of interest rate volatility, home price declines, or mortgage illiquidity. As shown in the accompanying charts, the increased interest rate and refinancing risks of shorter-duration mortgages translate into a consistently higher rate of foreclosures for these products, as compared to long-term fixed-rate loans. Note that all of the loans described in these charts are prime loans, made to borrowers with similar credit characteristics, and so the differences in foreclosure rate are purely attributable to the differences between long-term fixed-rate loans and shorter-duration loans.

As the above charts indicate, over the last decade, long-term fixed-rate mortgages consistently outperformed adjustable-rate mortgages made to the same prime borrowers. Since statistics have been available in 1998, prime adjustable-rate mortgages have been 2.72 times more likely to go into foreclosure than prime fixed-rate mortgages.

Moreover, this differential became much more pronounced since housing prices began to fall in 2007, with prime adjustable-rate mortgages having foreclosure rates of roughly five times the rates of prime fixed-rate mortgages. If interest rates had also risen during this period, then it is nearly certain that the foreclosure rates for adjustable-rate mortgages would have soared even higher.

Moreover, this differential became much more pronounced since housing prices began to fall in 2007, with prime adjustable-rate mortgages having foreclosure rates of roughly five times the rates of prime fixed-rate mortgages. If interest rates had also risen during this period, then it is nearly certain that the foreclosure rates for adjustable-rate mortgages would have soared even higher.

To reiterate, the 30-year fixed-rate mortgage is a more sustainable product than loans that must be refinanced every few years, providing significantly lower rates of mortgage default, both during good times and particularly during bad times. This is good for the housing markets and for the broader economy.

The 30-year fixed-rate mortgage places rate risk onto those parties best able to deal with it

A common refrain from critics of the 30-year fixed-rate mortgage is that this product unduly benefits borrowers at the expense of financial institutions and investors who must then deal with the interest rate risk. Between borrowers and lenders, someone has to hold this rate risk. Why should we favor borrowers?

The answer, simply put, is that lenders are far more capable of dealing with rate risk than borrowers. Households do not hire teams of analysts to predict interest rate fluctuations. Nor do they have access to complex derivative products designed to hedge against interest rate risk. Lenders do. Good lenders devote extensive resources to anticipating and planning for interest rate risk—this is in essence what they are paid to do. In obvious contrast, good firefighters, construction workers, nurses, and other working homeowners do not.

American households are already bearing enormous amounts of financial risk

As author Peter Gosselin notes, the past several decades have seen an enormous amount of financial risk transferred from business and the government to American households. Risks that were once largely borne by insurance companies, employers, or the government, such as the costs of major unemployment, illness, retirement or disability, are now increasingly being borne by American families, most of which are now more exposed than ever to the impacts of economic and financial volatility for which they have neither the expertise nor the time to effectively deal with.

Moreover, as Gosselin notes, 60 percent of the average American homeowner’s wealth is accounted for by the value of their primary homes. For the least wealthy half of American homeowners, that number is 75 percent. To force American homeowners to deal with interest rate and refinancing risk—for an asset that is by far the single most valuable portion of their household savings—on top of all of the other risks they already have to bear is unthinkably reckless and potentially catastrophic.

The idea of transferring these housing finance risks to consumers seems even more irrational when one factors in the infrastructure and expertise that mortgage lenders already have in place to deal with these risks.

The 30-year fixed-rate mortgage promotes housing market stability because it is less sensitive to interest rate changes

The 30-year fixed-rate mortgage is also important in limiting macroeconomic instability and facilitating monetary policy because it is less sensitive to shortterm interest rate fluctuations than shorter-duration mortgages. Indeed, this was a key finding of the so-called interim “Miles Report,” the landmark 2004 report on mortgage market reform in the United Kingdom written by David Miles, now a member of the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee.

Utilizing a combination of empirical data and modeling, Miles found that in countries where there was an abundance of short-term or adjustable-rate mortgages, short-term interest changes had a much larger impact on home prices. These findings matched those previously reached by the central bank of the Netherlands, which observed that housing markets dependent on short-duration mortgages were much more sensitive to short-term interest rate fluctuations than those dependent primarily on long-duration mortgages.

How much more sensitive? Research conducted in the early 2000s found that home prices in the United Kingdom, where short-duration mortgages are predominant, were approximately six times as sensitive to short-term interest rate changes as home prices in the United States, where the 30-year fixed-rate mortgage has been dominant.

Based on these findings, Miles concluded that the structure of a country’s housing finance was a prime contributor to macroeconomic volatility, and that a primary contributor to economic upheaval in the United Kingdom was its housing market volatility. Countries where bullet loans or variable-rate mortgages are the dominant product are far more vulnerable to extreme bubble-bust cycles in the housing markets, which can lead to larger economic instability.

If the United States transitioned away from 30-year fixed-rate mortgages, bubble-bust cycles would be much more common

In the United States, the idea of an economic boom-bust cycle driven almost exclusively by the housing markets was not part of our recent experience up until the 2000s, when not so coincidentally we saw a surge in short-term mortgage products. What the Miles Report suggests is that this type of boom-bust cycle would be far more common were we to switch to a mortgage system dominated by shorter-duration loans.

Indeed, recent history appears to provide evidence to this point. Denmark and the United States are the only countries in the world where the 30-year fixed-rate mortgage has been dominant, and during the reign of the 30-year mortgage both these countries generally enjoyed stable housing and financial systems. In the 2000s, both countries experienced an influx of shorter-duration products and both countries subsequently experienced large shocks to their housing and financial markets that have resulted in enormous costs for homeowners, investors, and taxpayers alike.

The 30-year mortgage enables flexibility in monetary policy

A system predominantly based on short-duration mortgages also limits the monetary policy options of a country’s central bank. The heightened sensitivity of such housing markets to short-term interest rates means that the impact of monetary policy on the housing markets is greatly amplified.

In countries where short-duration mortgages dominate, monetary policies that are desirable for the broader economy, such as credit easing, can easily set off a boom and bust cycle. For instance, in the early 2000s the Bank of England faced a situation in which manufacturing was very weak while house prices and mortgage borrowing were “exceptionally high.” Because Great Britain had so much variable-rate and short-duration mortgage debt in its markets, the Bank of England faced the highly undesirable option of keeping short-term rates low and further inflating its housing bubble, or raising rates at the expense of the broader economy.

Critics of the 30-year fixed-rate mortgage ignore the historically unique moment we are in

Critics of the U.S. 30-year fixed-rate mortgage often point to statistics from the recent past as evidence that shorter-duration mortgages are an appropriate substitute. You might hear the argument that “on average, Americans only keep their mortgages for five years to seven years before refinancing or moving, so all we really need is a five-year or five-year mortgage product.”

These types of arguments, relying on recent experience to justify a transition to a mortgage system dominated by shorter-duration loans, ignore that we are in (and perhaps near the end of) a historically freak period in which interest rates have declined while housing prices—at least until 2007—generally increased. (see Figure 3)

These types of arguments, relying on recent experience to justify a transition to a mortgage system dominated by shorter-duration loans, ignore that we are in (and perhaps near the end of) a historically freak period in which interest rates have declined while housing prices—at least until 2007—generally increased. (see Figure 3)

These conditions were essentially perfect for shorter-duration mortgages since the primary risks posed by these loans—interest rate risk and refinancing risk—essentially did not exist between 1980 and 2007! Borrowers were able to freely refinance and move because mortgage finance was cheap and widely available and home values were increasing.

In contrast, as recent history demonstrates, an increase in mortgage rates or a decrease in house prices can cause havoc in a housing market that is heavily reliant on shorterduration mortgages. Despite a climate in which interest rates have remained low, a sharp drop in house prices beginning in 2007 has caused a sharp increase in the difference between foreclosure rates on adjustable-rate and fixed-rate mortgages, as Figures 1 and 2 (above) illustrate. Were rates to rise, one would expect to see an even sharper increase in defaults on shorter-duration loans.

Conclusion

In short, despite the recent attacks on it, the 30-year fixed-rate mortgage remains the gold standard for mortgages throughout the world, offering superior stability for both homeowners and financial systems. By providing predictable payments, the 30-year fixed-rate mortgage leads to more stability for homeowners, reducing defaults, particularly during periods of interest rate or house price volatility.

The 30-year fixed-rate mortgage does not place interest rate risk or refinancing risk with American households who are already overburdened with financial risks, but rather places these with mortgage lenders who already have the infrastructure in place to plan for and hedge against these risks.

This product also supports macroeconomic stability by providing some insulation against wild price swings in the housing market due to short-term interest rate fluctuations and enhances the capacity of central banks to fully utilize their monetary policy tools with less fear of the undesirable repercussions in the housing markets.

In our next memo on the U.S. mortgage finance market we will present the argument on why the covered bonds that Europe uses to finance its mortgage needs are a poor fit for the United States. Watch this space.

David Min is Associate Director for Financial Markets Policy at the Center for American Progress.

Download the memo (pdf)

Download to mobile devices and e-readers from Scribd

See also: