For a more recent version of this information, see “Fast Facts: Economic Security for Women and Families in New Hampshire” by Shilpa Phadke, Diana Boesch, and Nora Ellmann.

This issue brief contains a correction.

When it comes to economic well-being, families in New Hampshire are experiencing a mixed blessing. On one hand, household incomes in New Hampshire are higher than the national average—thanks in no small part to the economic contributions of working women. But on the other hand, New Hampshire households have not reached new highs; they have simply rebounded from declining real incomes to reach the same point where they were in 2002, which is still well below the prerecession peak. And unfortunately, the real costs of the necessities for a middle-class life—things such as health care, education, and child care—are not the same as they were at the turn of the millennium. So the fact that New Hampshire households are doing better compared with the rest of the nation does not mean that they are immune to the economic squeeze being felt across the country.

Women have been central to the growth that the New Hampshire economy has experienced over the past 30 years. New Hampshire women are far more likely to work today, and their economic contributions to their families’ bottom lines have prevented circumstances for working families in the state from being much worse. But while the achievements of New Hampshire women are remarkable, there is much more to be done to ensure that New Hampshire’s women have a fair chance to stay in the labor force and reach their full potential. Because even when women work full time, they are nonetheless still the family members most likely to take on the majority of family care responsibilities, creating unique needs for working women and their families. Sensible policies to promote and support women’s employment nationally and in New Hampshire will enable families not only to get by but also to thrive. Supporting women’s employment is one important component of responding to rising costs of living and strengthening the middle class.

New Hampshire families have seen some economic gains, mostly due to women’s work

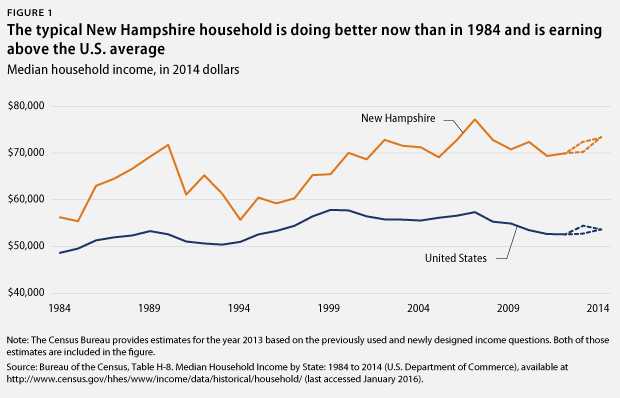

Middle-class New Hampshire families are, without a doubt, financially better off today than they were 30 years ago. During that span of time, real median household income in New Hampshire grew from $56,260 in 1984 to $73,397 in 2014, an increase of 30.46 percent. Moreover, New Hampshire families continue to do better than families in other states: While in 1984 the median household income in New Hampshire was roughly $7,600 higher per year than the national average in 2014 dollars, in 2014, the median New Hampshire household income was about $20,000 higher per year than the national average. (see Figure 1) This is due to an uptick in income in New Hampshire coupled with declining incomes nationally.

But a more in-depth look at the New Hampshire middle class shows that there are signs of trouble. Most disturbingly, middle-class incomes in New Hampshire are not substantially higher than they were in 1990—and nearly all of the median income growth over the past 20 years has been rebounding from a low point in 1994. And while incomes have not hit dramatic new highs, the cost of middle-class essentials has continued to grow unabated: The cost of attending a public university in New Hampshire, for example, more than doubled from roughly $10,000 per year in 2000 to more than $25,000 annually in 2014, even after adjusting for inflation.

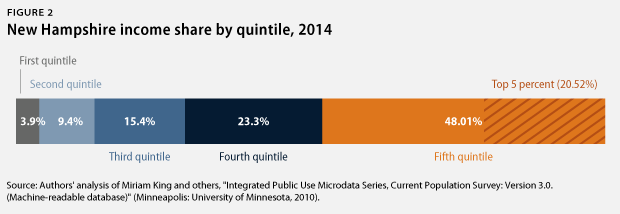

Moreover, income inequality is still a pressing concern in New Hampshire, as it is nationally. Across the United States, income is increasingly concentrated among the very few at the top of the income distribution. The Economic Policy Institute recently analyzed tax data to study state income growth and found that across the country, a large share of the gains experienced through the economic recovery have gone to the top 1 percent. From 2009 to 2012, the top 1 percent in New Hampshire captured 60 percent of all income growth. And in 2014, nearly half of all income went to the top 20 percent in the state, and one-fifth went to the top 5 percent. (see Figure 2)

So while income inequality remains a problem for New Hampshire families, the fact remains that New Hampshire households are doing better than average, at least in terms of median household income. So the question is: Why? What sets New Hampshire families apart from the rest of the country; what factors are essential to securing families’ economic stability; and what can be done to help make things even better in the Granite State?

New Hampshire women are key drivers of economic security

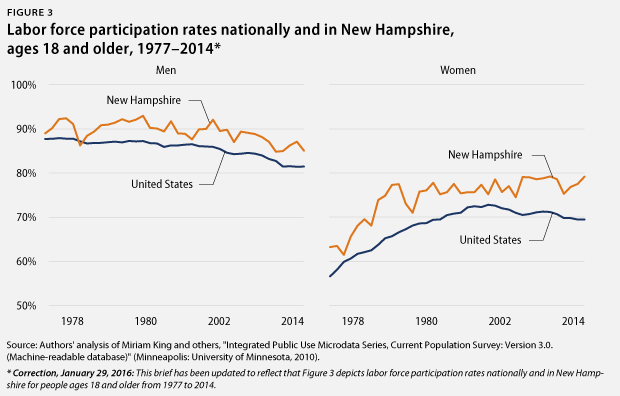

New Hampshire is unique for many reasons. Chief among these is the fact that women in New Hampshire are more likely to participate in the labor force than women in most other states: New Hampshire women’s labor force participation rates were fourth in the nation, coming after North Dakota, Iowa, and Nebraska in 2014. Labor force participation in New Hampshire is also high for men, but New Hampshire women stand out in comparison with their counterparts in other states due to their likelihood of working outside the home for pay. (see Figures 3a and 3b) While New Hampshire men have always been slightly more likely to be members of the labor force than men nationally, women’s labor force participation increased dramatically beginning in the 1980s. Today, women in New Hampshire are nearly 30 percent more likely to be in the labor force than women nationally.

On average, the only families who have seen real, inflation-adjusted income growth since the 1970s are married-couple families in which both parents work. Similarly, the White House Council of Economic Advisers has found that nearly all of the increase in family income from 1970 to 2013 was due to the increased earnings of women and that without the increased work of women, median family incomes would be about $13,000 per year lower today. And while women work outside the home for a wide variety of reasons—to find personal fulfillment, meet career goals, and explore and expand their strengths—for many, employment is an economic necessity. Simply put, most women—indeed, most people—work not only because they want to but also because they need to.

If not for working women, New Hampshire’s families and economy would fare much worse

New Hampshire women, through their labor force participation and economic contributions to their families, have helped stave off some of the worst economic effects being felt in other parts of the nation. Previous Center for American Progress research using national data has found that income inequality in the United States would be far worse had women not entered the labor force and significantly increased their earnings over the past several decades.

In a national analysis, CAP found that from 1963 to 2013, income inequality among the bottom 95 percent of all married couples grew roughly 25 percent. However, the growth of inequality would have been much starker without the increased earnings of women. Had women not increased their labor supply and earnings over this period, inequality would have risen 38 percent—in other words, income inequality would have grown more than 50 percent faster among married couples were it not for women’s labor force participation. Nationally, women’s increasing earnings have served as a powerful force against the rampant growth of income inequality. The data for New Hampshire show similar results. In a reprisal of this model using state-specific data, CAP found that if New Hampshire women had not increased their labor supply and earnings, inequality in the state would be 15 percent higher than it is today.

Working families need more

The economic contributions made by working women both nationally and in New Hampshire are of the utmost importance to the economic security of families and to the well-being of our economy overall. In addition to mitigating the effects of growing income inequality, women also contribute to the larger economy. Gross domestic product, or GDP, is 11 percent higher today—representing $1.7 trillion in economic output—than it would have been if women had not increased their number of work hours since the late 1970s.

But despite all the advances working women have made in New Hampshire and across the nation, much more remains to be done. Nationally, women who work full time, year round earn just 79 percent of what men earn for full-time, year-round work. In New Hampshire, this figure is even lower at 76 percent—a wage gap that represents a deficit of an average of $13,565 for full-time working New Hampshire women. The wage gap has complex causes, and much of this difference is due to the fact that women tend to work in different types of industries and occupations. Furthermore, in spite of their greater educational attainment, women tend to earn different types of degrees. Women in New Hampshire, for example, are more likely to work in low-wage jobs and are nearly 70 percent of all minimum wage workers in the state. But a significant portion of the gender wage gap is caused by differences in men and women’s work hours, job tenures, and total years of work experience—all of which are influenced by our nation’s shocking lack of work-family policies. The economic picture—at both the individual and the national levels—would look very different if we had public policies to support working families.

Recent Department of Labor analysis found that GDP would increase an estimated 3.5 percent—or more than $500 billion in additional economic activity—if women in the United States participated in the labor force at the same rates as women in Canada or Germany. While that might seem like a far-fetched dream, up until relatively recently, U.S. women ranked higher internationally for their labor force participation rates than women in other industrialized economies. But those rates have been falling, and at least part of the decline is due to the lack of family-friendly policies in the United States.

The United States remains the only advanced economy—in fact, one of the only countries in the world—that does not guarantee women the right to paid time off after the birth of a baby. And the United States is one of only a few wealthy countries that do not ensure workers the right to earn paid sick days that can be used if they or a family member fall ill or need to access preventive medical or dental care. Nationally, only 12 percent of private-sector workers have access to paid family leave, and the highest-paid workers are more than five times as likely to have access to the benefit than the lowest-paid workers. In New Hampshire, 38.9 percent of private-sector employees—more than 202,000 workers—do not have access to a single paid sick day if they become ill or need to care for a sick child. This is consistent with the national average of 39 percent of private-industry workers without paid sick days.

And even in the best-case scenarios in which working parents have access to the workplace benefits they need, such as paid leave, other problems can arise. The average cost of center-based care for an infant in New Hampshire is almost $12,000 per year, while the cost of care for a 4-year-old is only slightly lower at roughly $9,500. For the average single mother in New Hampshire, the cost of center-based infant care would represent more than 40 percent of her income. In either case, it would be less expensive for a family with two children to send these young New Hampshirites to an in-state public college than to pay for child care—a sad state of affairs which, along with the absence of paid leave, is a uniquely American phenomenon. In the United States, the cost of child care is high relative to other advanced economies, and public spending on child care is low by international standards.

Public policy solutions are needed in order to address the work-family issues facing working families today and to support working women fully. These include:

- Promoting equal pay. At the national level, the Paycheck Fairness Act would help ensure equal pay by taking steps to eliminate pay secrecy, which often prevents women from discussing their salaries with colleagues or obtaining the information they need to seek legal recourse to address pay discrimination.

- Increasing the minimum wage. Women in New Hampshire make up nearly 7 in 10 minimum wage workers, and increasing their wages would help promote their families’ economic security. If the minimum wage in New Hampshire were increased to $12 per hour, it would help one in five workers by putting more than $327 million into the pockets of working families.

- Guaranteeing access to paid sick days. Legislation such as the Healthy Families Act would enable workers to earn up to seven paid sick days per year that could be used if they or a family member were ill or needed to seek preventive care. Policies such as paid sick days help ensure that something as common as a child getting a cold does not result in a parent losing his or her job.

- Ensuring access to paid family and medical leave. Every worker will likely need time off to provide care during their working lives—to care for a new baby, tend to a seriously ill or injured family member, or recover from their own serious illness. Legislation such as the Family and Medical Insurance Leave, or FAMILY, Act would create a universal, affordable national program to provide wage replacement to workers who need family and medical leave. Three states—California, New Jersey, and Rhode Island—have implemented their own programs that also could serve as a model for New Hampshire and the rest of the nation.

- Making high-quality, affordable child care accessible. A new CAP proposal would provide up to $14,000 per child paid directly to child care providers that parents select. Families would contribute up to 12 percent of their incomes toward fees on a sliding scale. This proposal would save New Hampshire families an average of $5,985 per year and facilitate high-quality child care arrangements that support financial security for working families.

Conclusion

In the past three decades, America’s families have changed. Long gone are the days when most women stayed home to care for their children and perform unpaid domestic labor. As the women of New Hampshire have shown, women and mothers are vitally important economic contributors to their families’ economic security and their state’s economy. New Hampshire women and mothers have made great strides for their families but are prevented from reaching their full potential by a pernicious gender wage gap and outdated public policies that do not reflect the way America’s families live and work today.

Ensuring access to equal pay; increasing the minimum wage; guaranteeing the right to paid family and medical leave; allowing workers the right to earn paid sick days; and supporting access to affordable, high-quality child care would all work to strengthen women’s labor force attachment and help increase their earnings.

By implementing these types of policies, New Hampshire can ensure that working families continue to see household incomes that are higher than the national average, while supporting and encouraging the labor force participation of women. New Hampshire’s economy is strong and growing stronger in no small part because of these working women. These crucial investments in the future will ensure that the pattern continues for future generations.

Sarah Jane Glynn is the Director of Women’s Economic Policy at the Center for American Progress. Brendan V. Duke is a Policy Analyst for the Middle-Out Economics project at the Center. Danielle Corley is a Research Assistant for Women’s Economic Policy at the Center.

* Correction, January 29, 2016: This brief has been updated to reflect that Figure 3 depicts labor force participation rates nationally and in New Hampshire for people ages 18 and older from 1977 to 2014.