This month’s economic data shed some light on a recovery that, up until recently, seemed to have been treading water. Recent data show that the labor market is on the rise with the unemployment rate falling to 5.5 percent, its lowest rate since the end of the Great Recession. The unemployment rate for historically vulnerable groups, such as African Americans and Latinos, is finally at or near pre-recession levels. Additionally, February saw a gain of 295,000 jobs with an average of almost 300,000 jobs added per month over the past 6 months. There has also been modest economic growth with gross domestic product, or GDP, increasing at a fair rate of 2.2 percent between September 2014 and December 2014.

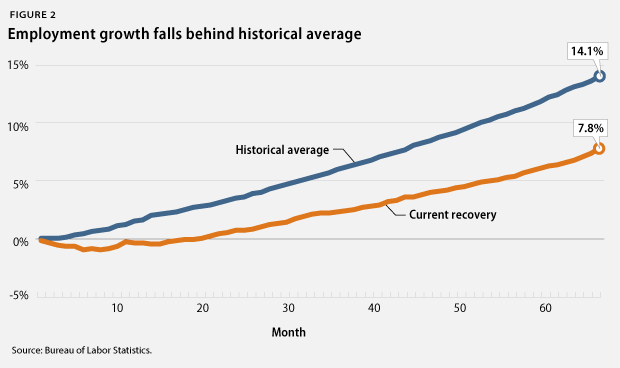

While these economic gains are promising, they still fall short by historical standards. The economy has expanded 13.6 percent since the end of the Great Recession, far below the historical average of 25.9 percent during prior recoveries of at least equal length. Employment levels show a similar trend: The total number of jobs has now grown 7.8 percent during this recovery compared to an average of 14.1 percent during all prior recoveries of at least equal length.

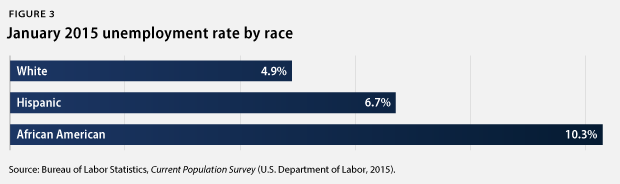

Additionally, although the unemployment rate for Latinos has fully recovered, returning to its pre-recession levels, and the unemployment rate for African Americans has recovered about 91 percent of the way, these vulnerable groups, among others, continue to struggle disproportionately compared with their white counterparts. Whereas the white unemployment rate remains below the national average at 4.7 percent, the African American unemployment rate is more than double that at 10.3 percent and the Hispanic unemployment rate remains high at 6.7 percent. Moreover, these communities continue to grapple with disparities in wages, poverty rates, and access to vehicles for saving.

It is quite evident that the weight of the Great Recession continues to fall on American workers, and the only way to relieve this pressure is to build an economy that boosts inclusive prosperity and bolsters a strong middle class. Policymakers can do so by focusing their efforts on measures that boost wages and provide vulnerable communities with a shot toward achieving the American dream.

1. Economic growth, while positive, has been lackluster for years: GDP increased in the fourth quarter of 2014 at an inflation-adjusted annual rate of 2.2 percent, after an increase of 5 percent in the previous quarter. Domestic consumption increased by an annual rate of 4.4 percent, and housing spending rose by 3.8 percent, while business investment grew at a slower rate of 4.4 percent. Exports only increased by 4.5 percent in the fourth quarter, while imports increased by a much faster rate of 10.4 percent, resulting in a widening trade deficit. Government spending continues to be a weak spot in the economy as federal government spending fell by 7.3 percent, and state and local government spending rose only by 1.6 percent. Economic growth improved in 2014 compared to earlier years of this economic recovery, which began in June 2009. But, the economy needs to maintain and even accelerate its momentum in order to create real economic security for America’s families. After all, the economy expanded 13.5 percent from June 2009 to December 2014, far below the average of 25.9 percent during recoveries of at least equal length.

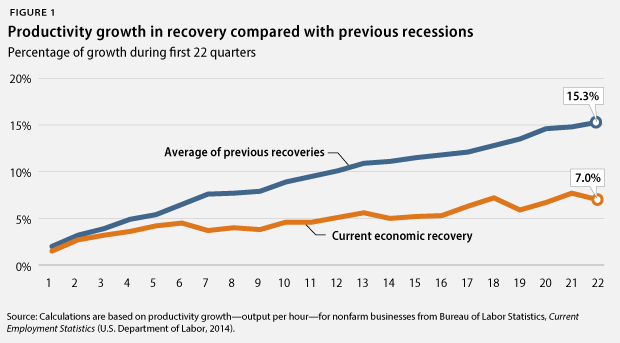

2. Improvements to U.S. competitiveness fall behind previous business cycles. Productivity growth, measured as the increase in inflation-adjusted output per hour, is key to strong economic growth over the longer term and to increasing living standards, as it means that workers are getting better at doing more in the same amount of time. Slower productivity growth thus means that new economic resources available to improve living standards are growing more slowly than would be the case with faster productivity growth. U.S. productivity rose 7 percent from June 2009 to December 2014, the first 22 quarters of the economic recovery since the end of the Great Recession. This compares to an average of 15.3 percent during all previous recoveries of at least equal length. No previous recovery had lower productivity growth than the current one. This slow productivity growth—together with high income inequality—contributes to the widespread sense of economic insecurity and slowing economic mobility.

3. The housing market is still only a shadow of its former self. New-home sales amounted to an annual rate of 539,000 in February 2015—a 24.8 percent increase from the 432,000 homes sold in Februrary 2014 but well below the historical average of 698,000 homes sold before the Great Recession. The median new-home price in February 2015 was $275,500, up from one year earlier.Existing-home sales rose by 1.2 percent in February 2015 from one year earlier, and the median price for existing homes was up by 7.5 percent during the same period. Home sales have a lot further to go, given that homeownership in the United States stood at 64 percent in the fourth quarter of 2014, down from 68.2 percent before the start of the recession at the end of 2007. The current homeownership rates are similar to those recorded in 1996, well before the most recent housing bubble started.A strong housing-market recovery can boost economic growth, and there is still plenty of room for the housing market to provide more stimulation to the economy more broadly than it did before the recent slowdown.

4. The outlook for federal budgets improves. The nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office, or CBO, estimated in March 2015 that the federal government will have a deficit—the difference between taxes and spending—of 2.7 percent of GDP for fiscal year 2015, which runs from October 1, 2014, to September 30, 2015. This deficit projection is slightly down from the deficit of 2.8 percent of GDP for FY 2014. The estimated deficit for FY 2015 is much smaller than deficits in previous years due to a number of measures that policymakers have already taken in order to slow spending growth and raise more revenue than was expected just last year. The improving fiscal outlook should generate breathing room for policymakers to focus their attention on targeted, efficient policies that promote long-term growth and job creation, especially for those groups disproportionately impacted by high unemployment.

5. Moderate labor-market gains follow in part from modest economic growth. There were 10.2 million more jobs in February 2014 than in June 2009. The private sector added 10.8 million jobs during this period. The loss of some 590,000 state and local government jobs explains the difference between the net gain of all jobs and the private-sector gain in this period. Budget cuts reduced the number of teachers, bus drivers, firefighters, and police officers, among others. The total number of jobs has now grown by 7.8 percent during this recovery, compared to an average of 14.1 percent during all prior recoveries of at least equal length. Faster economic growth is necessary to generate more labor-market momentum.

6. Employers cut back on health and pension benefits. The share of people with employer-sponsored health insurance dropped from 59.8 percent in 2007 to 53.9 percent in 2013, the most recent year for which data are available. The share of private-sector workers who participated in a retirement plan at work fell to 40.8 percent in 2013, down from 41.5 percent in 2007. Families now have less economic security than they did in the past due to fewer employment-based benefits, not just because of modest job and wage gains.

7. Some communities continue to struggle disproportionately from unemployment. The unemployment rate was 5.5 percent in February 2014. The African American unemployment rate increased slightly to 10.4 percent, the Hispanic unemployment rate fell slightly to 6.6 percent, and the white unemployment rate also fell slightly to 4.7 percent. Meanwhile, youth unemployment decreased to 17.1 percent. The unemployment rate for people without a high school diploma was 8.4 percent, compared with 5.4 percent for those with a high school degree, 5.1 percent for those with some college education, and 2.7 percent for those with a college degree. Population groups with higher unemployment rates have struggled disproportionately more amid the weak labor market than white workers, older workers, and workers with more education.

8. The rich continue to pull away from most Americans. Incomes of households at the 95th percentile—those with incomes of $196,000 in 2013, the most recent year for which data are available—were more than nine times the incomes of households in the 20th percentile, whose incomes were $20,900. This is the largest gap between the top 5 percent and the bottom 20 percent of households since the U.S. Census Bureau started keeping records in 1967. Median inflation-adjusted household income stood at $51,939 in 2013, its lowest level in inflation-adjusted dollars since 1995.

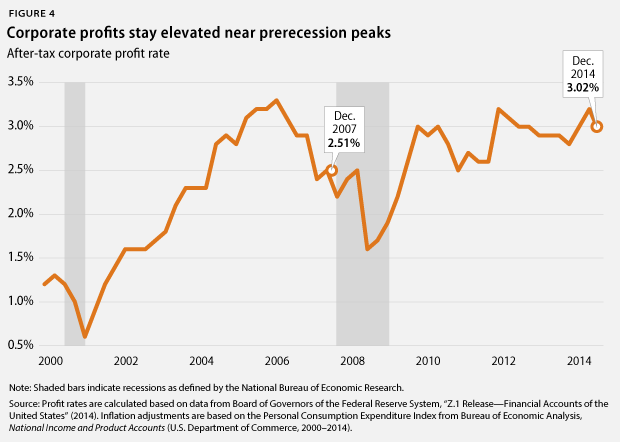

9. Corporate profits stay elevated near pre-crisis peaks. Inflation-adjusted corporate profits were 102.7 percent larger in December 2014 than in June 2009. The after-tax corporate profit rate—profits to total assets—stood at 3 percent in December 2014. Corporate profits recovered quickly toward the end of the Great Recession and have stayed high since then. Addressing income inequality that arises from the rich receiving outsized benefits from their wealth through tax reform is a crucial policy priority.

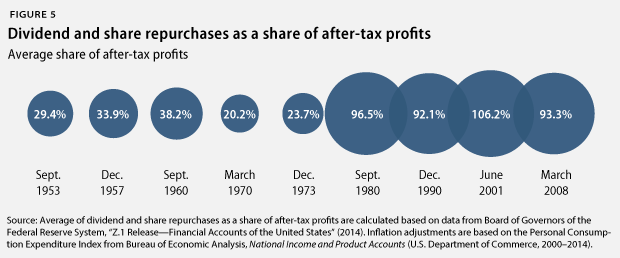

10. Corporations spend much of their money to keep shareholders happy. From December 2007—when the Great Recession started—to December 2014, nonfinancial corporations spent, on average, 97.8 percent of their after-tax profits on dividend payouts and share repurchases. In short, almost all of nonfinancial corporate after-tax profits have gone to keeping shareholders happy during the current business cycle. Nonfinancial corporations also held, on average, 5.4 percent of all of their assets in cash—the highest average share since the business cycle that ended in December 1969. Nonfinancial corporations spent, on average, 168.7 percent of their after-tax profits on capital expenditures or investments—by selling other assets and by borrowing. This was the lowest ratio since the business cycle that ended in 1960. U.S. corporations have prioritized keeping shareholders happy and building up cash over investments in structures and equipment, highlighting the need for regulatory reform that incentivizes corporations to invest in research and development, manufacturing plants and equipment, and workforce development.

11. Poverty is still widespread. The poverty rate was 14.5 percent in 2013, down from 15 percent in 2012. This change, however, was statistically insignificant. Moreover, the poverty rate for this recovery increased at a rate of 0.2 percentage points, compared to an average decrease of 0.7 percentage points in previous recoveries of at least equal length. Some population groups suffer from much higher poverty rates than others. The African American poverty rate, for instance, was 27.2 percent, and the Hispanic poverty rate was 23.5 percent, while the white poverty rate was 9.6 percent. The poverty rate for children under age 18 fell to 19.9 percent. More than one-third of African American children—37.7 percent—lived in poverty in 2013, compared with 30.4 percent of Hispanic children and 10.7 percent of white children.

12. Household debt is still high. Household debt equaled 102.5 percent of after-tax income in December 2014, down from a peak of 129.7 percent in December 2007. But, nonrevolving consumer credit—typically installment credit such as student and car loans—has outpaced after-tax income growth. It has grown from 14.6 percent of after-tax income in June 2009 to 18.4 percent in December 2014. A return to debt growth outpacing income growth—which was the case for total debt prior to the start of the Great Recession—from already-high debt levels could eventually slow economic growth again. This would be especially true if interest rates also rise from historically low levels due to a change in the Federal Reserve’s policies. Consumers would have to pay more for their debt, and they would have less money available for consumption and saving.

Christian E. Weller is a Senior Fellow at the Center for American Progress and a professor in the Department of Public Policy and Public Affairs at the McCormack Graduate School of Policy and Global Studies at the University of Massachusetts, Boston. Jackie Odum is a Research Assistant for the Economic Policy team at the Center.