Over the past decade, Congress dramatically cut the IRS’ budget and with it, the agency’s capability to enforce the nation’s tax laws. New data released by the IRS, as well as reports from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and U.S. Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration (TIGTA), underscore the toll that IRS budget cuts have taken. The reports and data provide even more evidence that the IRS needs to be substantially rebuilt, with its priorities directed toward policing tax cheating by wealthy individuals and corporations.

New IRS data show the toll of diminished resources

In June, the IRS released its data book for fiscal year 2019, which showed just how serious the toll of diminished resources on audit coverage has been. In fiscal year 2010, the IRS received around 230 million returns and employed 13,879 revenue agents. By fiscal year 2019, the agency was receiving 253 million returns—nearly a 10 percent increase. However, due to budget cuts, it had just 8,526 revenue agents employed to examine them.

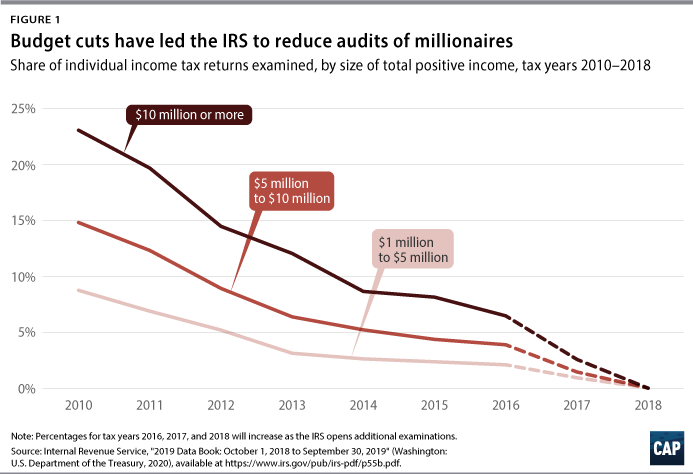

The share of tax returns that the IRS audited, especially for ultrawealthy individuals and businesses, has fallen dramatically as a result. In tax year 2010, the IRS examined nearly one-quarter of individual income returns with a reported income of $10 million or higher, but since then, audit coverage has dropped precipitously. In tax year 2015, for which no new examinations will be opened, audit coverage had fallen by two-thirds, meaning just 8.16 percent of returns with reported incomes of $10 million or more were examined. For 2018 returns, the IRS has opened audits on only 0.03 percent of the ultrahigh-income group. That number will likely climb as the IRS opens new cases for that year, although the downward trend in audit coverage is clear.

The new data reveal how the agency has made a substantial shift away from auditing wealthy taxpayers, while still disproportionately auditing the low-income claimants of refundable tax credits. Between 2011 and 2019, the audit rates for those earning more than $1 million fell by 81 percent. Audit rates for those claiming the earned income tax credit on the other hand, have fallen much less drastically—by just about 50 percent. Now, the IRS audits millionaires at close to the same level as working-class taxpayers with less than $20,000 of annual income. Similarly, audits for the wealthiest corporations—those with assets of more than $10 million—declined much more rapidly than for corporations with fewer assets. IRS Commissioner Charles Rettig has said that the agency cannot increase coverage of high-income individuals and corporations with its current resources, given that such audits require more highly trained examiners than the IRS currently has.

CBO data show the impact of high-income tax avoidance

The CBO released a June report that reinforces many of these findings. The agency was blunt: “Since 2010, the IRS has done less to enforce tax laws.” The report documents how cutting IRS budgets over the last decade has reduced tax enforcement resources, with the most pronounced effects on high-income individuals and the largest corporations. The failure to enforce the tax laws has significantly added to the tax gap—or the difference between taxes owed and what is collected. The most recent data from the IRS estimate that from 2011 to 2013, the agency was unable to collect $381 billion in taxes, even after audits. The largest source of this gap came from business owners underreporting income on their individual tax returns. While the IRS does not produce distributional analysis as part of its tax gap report, professors Lawrence Summers and Natasha Sarin have estimated that 70 percent of this underreporting came from the richest 1 percent. The rich are responsible for an outsize share of the tax gap both because they would owe more taxes in a progressive tax system—and because they have more opportunities to dodge taxes than people such as wage earners or Social Security recipients. Income for wage earners and Social Security recipients is highly visible to the IRS because of third-party reporting, primarily quarterly payroll tax returns filed with the IRS by employers. The IRS has much less visibility into business income and capital gains, however, which flow overwhelmingly to people with high incomes.

This doesn’t have to be the case. In its report, the CBO provided new analysis that estimated that increasing IRS funding by just $20 billion over the next 10 years would help close the tax gap by bringing in an additional $61 billion dollars in tax revenue or $103 billion from $40 billion of additional funds. The CBO’s report thus reinforces what is already known: From the perspective of the federal budget, investments in tax enforcement pay for themselves and then some. These estimates are very conservative, since the CBO only included the direct effects of IRS budget increases in its analysis; in other words, the CBO only estimated the actual revenue collected directly from audits and other enforcement actions. Other estimates that incorporate indirect effects—such as the deterrent effect that better enforcement has on tax cheating—are significantly higher. The U.S. Treasury has estimated that $1 for enforcement directly raises $6 in revenue and three times that in indirect revenue, for a total return of $24 for each $1 spent. Other research into the indirect effects find that they are even larger. Because of Congress’ scorekeeping rules, none of the increased revenue, direct or indirect, is taken into account in the official scores of legislation that would increase IRS funding—a rule that needs to be changed so that budget estimates of investments in tax enforcement are more accurate.

The IRS is failing to go after high-income people who do not even file tax returns

Finally, a recent report from TIGTA starkly illustrates just how serious the IRS’ failure to pursue high-income tax delinquents has become. TIGTA released the findings of its investigation into the IRS’ handling of high-income nonfilers—people with incomes of $100,000 or more who completely failed to file tax returns or filed incomplete returns. TIGTA found that as of the end of 2018, nearly 900,000 high-income Americans had failed to satisfy their requirement to file income tax returns for the years 2014 through 2016. These high-income delinquents accounted for most of the nonfiler tax gap—the total amount of tax that went uncollected from people failing to file returns. Altogether, they owed an estimated $45.7 billion to the IRS, with the top 100 nonfilers alone owing $9.9 billion. Nearly 30 percent of these nonfilers owed more than $1 million in taxes each. According to the report, the IRS completely failed to follow up with 369,180, or 42 percent, of the high-income nonfilers, while the other 510,235 were “sitting in one of the Collection function’s inventory streams and will likely not be pursued as resources decline.”

Auditing the often complex financial situations of wealthy individuals requires more people, resources, and training to work the case. Cuts to the IRS budget and staff over the last decade—particularly to personnel who support enforcement—have constrained the IRS’ ability to adequately perform these tasks, and the nonfiler component of the tax gap has grown as a result.

The IRS needs to be rebuilt and refocused

In a March report, the Center for American Progress made several recommendations to address each of these issues, including: increasing funds for IRS enforcement and placing more focus on those with higher incomes; changing Congress’ budget scorekeeping rules to incorporate revenue gains from IRS enforcement; expanding the scope of information reporting and withholding; and better regulating tax preparers.

Tax enforcement is about not just collecting needed revenue but also unrigging the economy for workers and honest taxpayers, while making sure the wealthy pay their fair share. These recent reports show the urgency of funding the IRS.

Galen Hendricks is a research assistant for Economic Policy at the Center for American Progress. Seth Hanlon is a senior fellow at the Center.