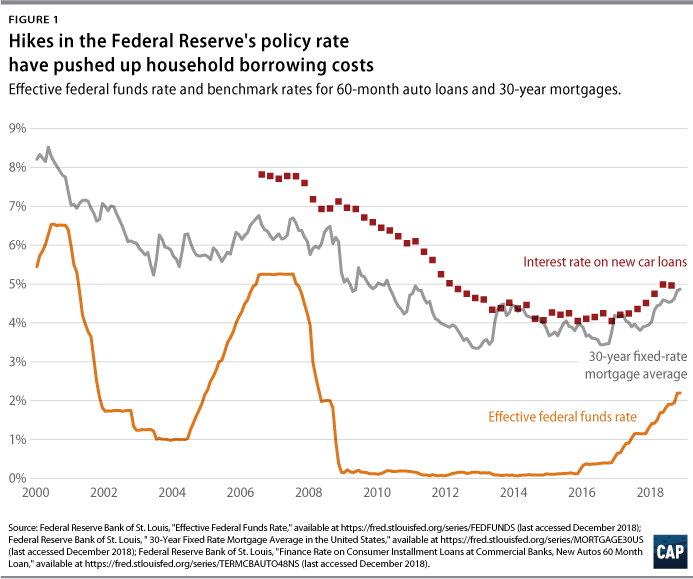

On Friday, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics will release its Employment Situation Summary for the month of November. The following week, during the Federal Open Market Committee’s final meeting of 2018, the Federal Reserve is expected to raise interest rates for the fourth time this year. The Fed last raised its benchmark rate in September, and another rate hike would mark the bank’s eighth raise since 2015. While the Fed has typically been a key support for a faster-growing economy, this gradual tightening of monetary policy has shifted its focus toward a pre-emptive slowdown that will be disproportionately felt by those already facing the largest hurdles in the labor market.

Although the Fed is constrained primarily by its dual mandate of stable prices and maximum employment, it appears that the implicit duty to maintain financial stability is currently weighing heavily on the bank, contributing to its inclination to pump the breaks on the economy. While employment growth remains consistent and inflation is well below the Fed’s stated target of 2 percent, there are legitimate concerns about rising asset prices—or at least there were earlier this year. Higher interest rates would raise the cost of borrowing for businesses and the government, meaning less money to spend and potentially slowing the growth of investment in and prices of financial and real estate assets. Already, there are clear signs that the housing market is cooling, and the stock market has declined significantly this fall. Yet even as the rationale for slowing the economy has weakened, it seems almost certain that the Fed will raise interest rates once again.

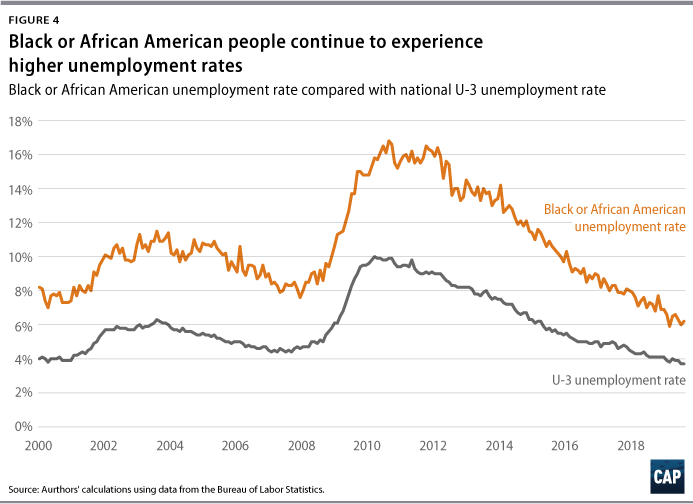

Meanwhile, some of the country’s most disadvantaged workers—including blue-collar workers, workers without a college degree, and workers of color—have been left out of the discussion on rising asset prices. Many of these workers have not yet reaped or have just started to reap the benefits of rising asset prices because they do not own stocks, bonds, or homes. The unemployment rates for black or African American and Hispanic workers, for example, are significantly higher than the overall unemployment rate.

Recognizing the tension between the Fed’s focus on asset prices and the real economy, Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis President Neel Kashkari recently pointed out, “If the U.S. economy is creating 200,000 jobs a month, month-after-month, we’re not at maximum employment.” Just last week, the Fed issued a cautionary note concerning risks to financial stability that could result from global financial uncertainty, trade tensions, and the bank’s own interest rate hikes—which further suggests that, despite evidence that the labor market still has room to grow, the full-employment mandate is routinely overlooked.

This column presents labor market indicators to watch in evaluating both the health of the U.S. economy and the effects of the policy priorities of the Trump administration and its congressional allies. Although the headline unemployment rate—otherwise known as U-3—is the most frequently cited indicator of labor market health, other factors can provide a more complete picture of how the economy is performing and whether lower unemployment is translating into wage gains for all workers. The number of people working part time for economic reasons and the U-6 unemployment rate—both discussed below—are two of these factors. Additionally, it is important to note how each labor market indicator differs across demographics—for example, by race. Although the national unemployment rate may be low, this indicator can tell a different story for other demographic groups.

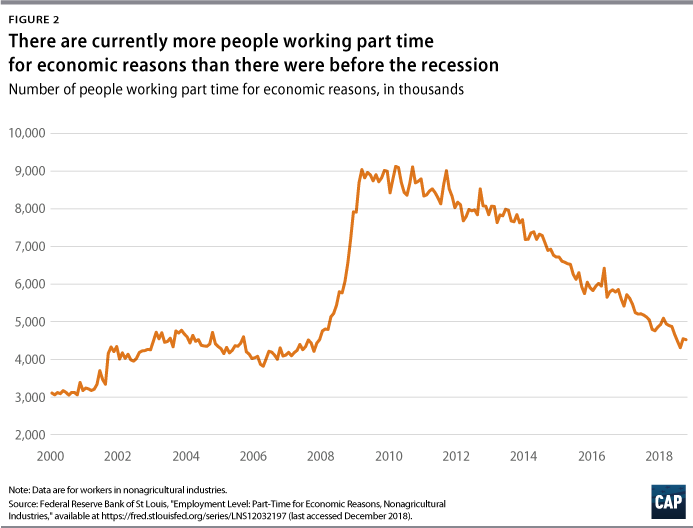

The number of people working only part time for economic reasons remains very high

The number of workers who are employed only part time for economic reasons—meaning that they are unable to find full-time work despite wanting it—remains high compared with prerecession levels. If workers are part-time because their hours are cut or because they cannot find a full-time job, that indicates a labor market that is less favorable for all workers. In October 2018, there were roughly the same number of involuntary part-time workers, 4.5 million, as in the previous month—still significantly higher than the precrisis low of 3.8 million in April 2006.

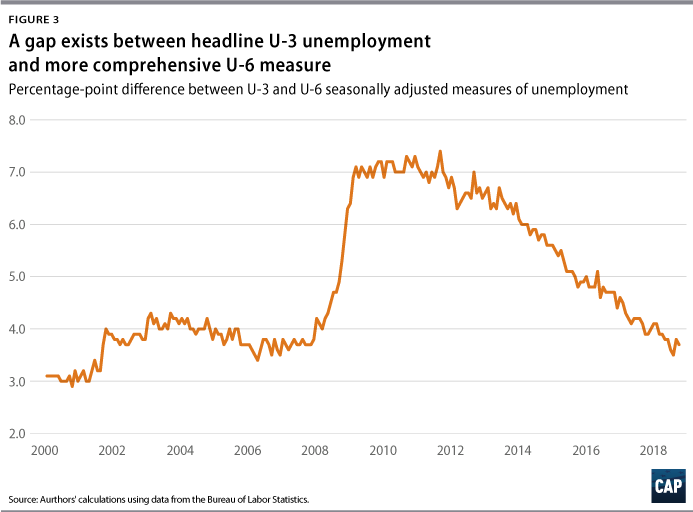

U-3 vs. U-6

The U-3 unemployment rate, the most common unemployment measure, can underestimate those who are unable to find jobs. For example, it does not capture the people who want jobs but have given up looking for work or the people who would like full-time work but can only find part-time positions. Perhaps the most comprehensive unemployment measure, U-6 alleviates this problem by including marginally attached workers—those who have recently looked for work but are not currently looking—and part-time workers who would prefer full-time work. A low U-6 indicates that people who face greater barriers in finding employment are being pulled back into the labor market due to greater economic opportunity. U-6 is always higher than U-3, but the gap grew much larger than usual during the recession and has remained above or near prerecession records over the course of the recovery.

The unemployment rate has not recovered to prerecession rates for all demographics

The gains from the recovery have not been experienced equally among different demographics, and those with historically worse labor market conditions continue to face higher unemployment rates with long-term detrimental effects. The overall unemployment rate fell from 10 percent to 3.7 percent between October 2009 and October 2018, and the rate for black or African Americans dropped from 15.8 percent to 6.2 percent during the same time frame; however, there is still a significant gap. Younger people also face disproportionately high unemployment rates, with black or African American youth suffering from unemployment rates that are more than four times that of the overall population.

Focusing on the groups whose unemployment rates continue to have room for improvement should be a benchmark for the health of the U.S. labor market overall. Expanding their opportunities in the labor market can be a source of future economic growth.

Conclusion

Friday’s employment data will provide an updated snapshot of the U.S. economy and labor market performance. Although the headline U-3 unemployment rate is an important indicator, the U-6 measure, in addition to focusing on the unemployment gaps along the lines of race and age, may serve as a more effective marker of the health of the economy. It is important to understand the economic outcomes that exist across different ages and across demographic groups. Although the economy is doing well in the aggregate, more work needs to be done to bring individuals back into the labor market.

With this in mind, the Fed should calibrate policy toward maximizing the health of an economy that is still recovering for many people, especially those who are most vulnerable in the labor market. In order to maintain economic growth, this administration must take these data into serious consideration in its decision-making.

Daniella Zessoules is a special assistant for Economic Policy at the Center for American Progress. Galen Hendricks is a special assistant for Economic Policy at the Center. Michael Madowitz is an economist at the Center.