Introduction and summary

When voters cast a ballot, they expect their votes to matter in choosing representatives who are responsive, reflective, and accountable to the communities they represent. Election districts for federal, state, and local offices should be drawn to advance those ends. Unfortunately, politicians in many states have manipulated election districts to choose their voters, rather than having voters choose them.1

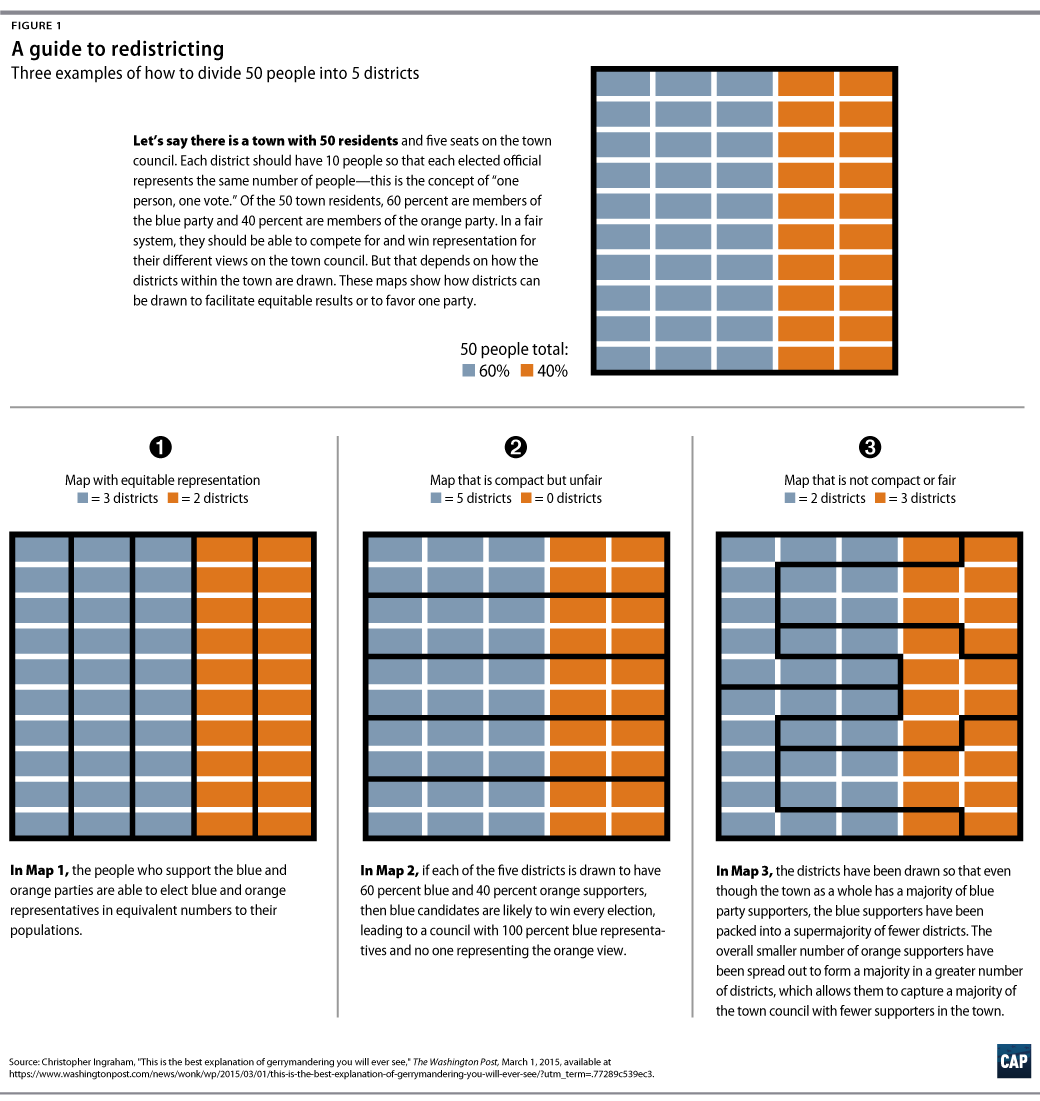

Electoral maps must follow the principle of “one person, one vote,” in which each district has a substantially similar number of people. But in most states, legislators can draw election districts in ways that manipulate the map for their own interests—called gerrymandering. For example, gerrymandering can tilt the playing field in favor of the politicians or party in power.2 Allowing politicians to draw their own election districts without checks and balances is like letting the fox guard the henhouse.

When elected officials are given exclusive, unfettered power to manipulate district lines, voters lose. Members of the U.S. House of Representatives are re-elected 97 percent of the time.3 And in the 2016 election, only 10 percent of the 435 House seats were considered competitive.4 In addition to creating an electoral process largely free of electoral choice and healthy competition, gerrymandering can insulate politicians from accountability and block communities from receiving meaningful and fair representation. In 2012, Democrats in the U.S. House of Representatives received 1.4 million more votes than Republicans, but Republicans won the majority of seats.5 That election marked the first time since 1972 that the party with the most votes did not get the most seats in Congress.6 Advances in technology have exacerbated the problem of gerrymandering by making it easier for map drawers to identify neighborhood demographics and voter preferences. Politicians are able to use this technology to slice and dice voters into districts along partisan and racial lines more precisely than ever before.7

Americans are taking matters into their own hands by advancing redistricting reforms to revitalize their elected representation and by filing lawsuits challenging corrupted district maps. People are winning victories for policy reforms, such as the recent success in California, where voters passed an initiative to set up an independent redistricting commission.8 Legal challenges to improperly drawn maps continue to move through the courts. Since 2010, 224 lawsuits challenging district lines have been filed across the country, 32 of which are still active.9 In November 2016, a federal court in Wisconsin struck down the state’s 2011 state assembly district maps as unconstitutional, marking the first time a state legislative redistricting plan was ruled unconstitutional for partisan gerrymandering.10 The court there found that Republicans had manipulated the state’s legislative boundaries for partisan advantage. Also in November 2016, a federal court ordered North Carolina lawmakers to redraw their state legislative districts after finding that lawmakers unconstitutionally relied on race when drawing district boundaries.11 On December 5, the U.S. Supreme Court will hear oral arguments in two redistricting cases involving challenges to districts in Virginia and North Carolina.

Some states are not waiting around for a court ruling to make their redistricting processes fairer and more representative. Several states have established independent redistricting commissions, and Florida incorporated clear criteria governing the process of drawing districts into its state constitution.

Americans are tired of having their voting power and representation manipulated by politicians who draw district maps to further their own interests. If citizens want elected representatives who reflect their priorities and preferences, they must push for reforms that will result in fair boundaries for election districts. The Center for American Progress recommends that states:

- Establish independent redistricting commissions

- Ensure clear redistricting criteria

- Promote public input and transparency in their redistricting processes

By putting these mechanisms in place, reflective and responsive representation may be fully realized and enjoyed by all Americans.

How the redistricting process works

Each decade, jurisdictions redraw the maps that determine their electoral districts to account for changing demographics. Districts are usually drawn by elected officials in the state legislature or city councils or, in a few places, by independent commissions. In other jurisdictions, an independent commission is responsible for drawing district maps, but the legislature has final approval.12

The Supreme Court has read the U.S. Constitution to require that districts for congressional races must have equal population “as nearly as is practicable” and that state legislative districts have “substantial equality of population.”13 In addition to equal population, many states impose other requirements to govern map drawing, such as respecting the boundaries of municipalities.

Those who draw maps for elections must also be cognizant of elected representation for communities of color. Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act prohibits laws or practices that “dilute” the political influence of voters of color by denying them an equal opportunity “to elect representatives of their choice.”14 In practice, this prohibits map makers from splitting communities of color into several different districts—known as “cracking”—while also forbidding the practice of “packing” as many voters of color as possible into a single district, which minimizes their influence elsewhere. In cases challenging post-2010 Census maps, federal courts have reiterated that states cannot use this requirement to pack African American voters into majority-minority districts, unless that is actually required to preserve their ability to elect their preferred candidates.15

Some jurisdictions allow the public to review the plans prior to implementation. In some jurisdictions, members of the public submit district maps for consideration. Other states allow citizens or state judges to vote on proposed maps, while others require review of all district maps by state judges before they are put into effect. Some states do not require public review or input at all.

Gerrymandering hurts voters

When district lines are manipulated, the democratic process is turned on its head. Voters may not be able to elect who they want, while map drawers are able to skew election results to favor themselves. And when politicians are guaranteed to win because gerrymandering has effectively precluded competitive elections, it diminishes responsiveness, accountability, and the potential for fair representation of all their constituents.

Representational mismatch

Redistricting can skew representation. In Pennsylvania in 2012, Democratic candidates received roughly 50 percent of the votes in House races, but Republicans took 75 percent of congressional seats.16 The same thing occurred in North Carolina, where Democrats received more than half of all votes, but Republicans claimed 70 percent of congressional seats.17 In Michigan too, despite Democratic candidates winning the most votes in 2012, Republicans took the majority of seats.18 Voters in Michigan experienced the same thing again in 2014, when Republicans retained congressional control despite Democratic candidates receiving the majority of votes.19 In Maryland in 2014, Democratic candidates received 57 percent of the vote but won seven out of eight House seats.20

On the state level, despite Democrats in Ohio winning more than 50 percent of the popular vote cast for the state legislature in 2012, Democratic members held just 39 of 99 seats in the wake of that election.21 In five other state legislatures, people cast more votes for candidates from one of the major parties, but the other party still controlled the state legislature.22

This mismatched pattern continued through this year’s election cycle in places such as Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, and repeat offender Michigan. In Pennsylvania, voters cast ballots for Democrats and Republicans in near equal numbers, yet 13 of the state’s 18 congressional seats went to Republicans.23 In Wisconsin, votes cast for Democratic and Republican candidates in statewide races were split roughly 50-50, but thanks to the GOP’s district manipulations, Republicans won control of nearly two-thirds of the legislature.24 And just as in 2012 and 2014, voters in Michigan saw Republicans retain control of the legislature, even though Democratic candidates once again received the majority of votes.

Noncompetitive elections

When politicians manipulate election maps, they can stifle competition and ensure incumbent candidates keep their seats. Because of gerrymandering, the political majorities of the incoming state legislatures in eight states were already decided before even a single vote was cast in the 2016 general election, while seven state legislature majorities were decided even before the primary election.25 In those places, district lines were drawn to ensure that only one major party candidate was viable to run in uncontested races.26 Only 4 percent of districts nationwide were decided by five percentage points or less, while only eight percent were decided by 10 points or less.27 Ninety-two percent of elections for seats in the House of Representatives were decided by a margin of victory exceeding 10 points.28

Policy outcome mismatch

The manipulation of election districts also has broader effects on the health of states’ democracy, according to a 2015 Center for American Progress Action Fund report.29 It “creates an echo chamber in which candidates and elected officials are responsible only to people of like demography and ideology, rather than to a broad base of voters.”30

As a result, they are able to pass laws that are averse to the interests and desires of those they represent. For example, in Michigan, where elected leaders have a long history of manipulating district lines, controversial legislation has been funneled through the state legislature, despite vehement opposition from voters.31 For example, “over a clear majority of residents’ objections,” Michigan lawmakers passed a controversial “rape insurance” law in 2014 and the state’s Religious Freedom Restoration Act in 2015.32 Only 36 percent of Michigan voters supported the rape insurance law, which required women to purchase a separate insurance policy for any future nonemergency abortion procedure.33 Moreover, 70 percent of Michigan voters wanted marriage equality protections expanded in 2015.34 This is in contrast to the state’s Religious Freedom Restoration Act, which allowed adoption agencies to deny service to same-sex couples.35 In 2012, Michigan voters rejected the state’s emergency manager legislation through referendum, legislation that would have allowed the state to strip locally elected governments of their power.36 However, elected officials ultimately ignored the clear wishes of their constituents a year later, when they passed the law and used the authority to strip the municipal governments of Flint and other cities of their authority.37 Unfortunately, because of the state’s manipulated district maps, Michigan voters did not have any realistic opportunity to vote these representatives out of office.

Legal guidelines for drawing election districts

In November 2010, the same year as the last census, conservative state legislators rode the so-called tea party wave to take control of state legislatures across the country.38 State legislators then redrew election districts using improper criteria and considerations.39 Many of these maps were challenged in court for discriminating against voters of color or members of a particular political party. Challenges can be brought against the way districts are apportioned at the federal, state, or local level.

For decades, the Supreme Court has recognized that if legislators draw maps with the improper goal of gaining too much partisan advantage and hobbling their political opponents, they could violate the Constitution.40 But the Court has thus far been unable to agree on a standard for determining how much partisanship is too much.41 The lack of clear legal rules has meant that states can generally get away with drawing districts for partisan benefit, but cases that are now being tried could help rein in overly partisan map drawing.

A new measure of map manipulation is emerging, called the “efficiency gap,” and it could result in a workable standard for determining how much partisanship in drawing districts is too much.42 The efficiency gap was developed by two scholars and is based on two numbers: votes cast for a losing candidate and surplus votes—the votes cast for a winning candidate in excess of what the candidate needed to win.43 These two numbers are added together then divided by the total number of votes to get the efficiency gap.44 For example, a federal court recently documented an extensive efficiency gap at work in two recent Wisconsin State Assembly election cycles:

In both elections held under the 2011 redistricting map the Republicans obtained a far greater proportion of the Assembly’s 99 seats than they would have without the leverage of a considerable and favorable [efficiency gap]. In 2012, the Republicans won 61% of Assembly seats with only 48.6% of the statewide vote, resulting in a 13% [efficiency gap] in their favor. In 2014, the Republicans garnered 52% of the statewide vote but secured 64% of Assembly seats, resulting in a pro-Republican [efficiency gap] of 10%. Thus, the Republican Party in 2012 won about 13 Assembly seats in excess of what a party would be expected to win with 49% of the statewide vote, and in 2014 it won about 10 more Assembly seats than would be expected with 52% of the vote.45

One of the scholars who created this measurement explained, “When a party gerrymanders a state, it tries to maximize the wasted votes for the opposing party while minimizing its own, thus producing a large efficiency gap.”46

The problem of improper partisan gerrymandering has grown in recent decades, and while a few maps favor Democrats, most favor Republican politicians.47 In 2012, there were seven maps that had an efficiency gap equivalent to at least two seats in the House of Representatives, and all favored Republicans.48 The scholars found a two-seat partisan advantage in conservative states such as Texas, North Carolina, and Virginia, as well as in crucial battleground states such as Michigan, Florida, Ohio, and Pennsylvania.49 Florida and Ohio had maps with a three-seat advantage for Republican politicians. Pennsylvania Republicans had a four-seat advantage.50

The federal court in the Wisconsin case recently struck down the map of state legislative districts for partisan gerrymandering under this new measure of manipulation.51 The ruling by a three-judge panel, which includes two judges appointed by Republican presidents, relied on the efficiency gap as supporting evidence of “an aggressive partisan gerrymander.”52 The court found that the legislature’s map was intended to “secure Republican control of the [legislature] under any likely future electoral scenario for the remainder of the decade, in other words to entrench the Republican Party in power.”53 The court said that “even when Republicans are an electoral minority, their legislative power remains secure.”54

The efficiency gap demonstrates that politicians in these states have stacked the deck to their partisan advantage. The new measure could be the kind of clear standard that the Supreme Court has not yet found in other cases. In 2004, the Court rejected a partisan gerrymandering lawsuit, and Justice Anthony Kennedy said, “The failings of the many proposed standards for measuring the burden a gerrymander imposes on representational rights make our intervention improper.”55

Lawsuits in North Carolina and Maryland also argue that manipulating maps for partisan advantage violates the First Amendment rights of voters.56 Justice Kennedy said that courts should closely examine maps that are “burdening or penalizing citizens because of their participation in the electoral process, their voting history, their association with a political party, or their expression of political views.”57

The North Carolina lawsuit claims that Republican legislators used “data about Democratic voters’ political expression to retaliate against them and to prevent them from meaningfully participating in the political process. This burden or penalty, moreover, is entirely intentional.”58 The plaintiffs in a North Carolina case filed in September 2016 by the Southern Coalition for Social Justice invoked the efficiency gap theory.59 The coalition told the federal court that even if Democratic congressional candidates won a majority of the statewide vote, the maps would “enable Republican candidates to win ten of thirteen seats. Indeed, even if the largest Democratic wave in a generation occurs, the plan will still produce a Republican supermajority.”60

In North Carolina and other Southern states, Republican politicians have tried to justify biased maps by pointing to the Voting Rights Act of 1965, or VRA, claiming the law required them to pack black voters into majority-minority districts after the 2010 Census.61 The VRA requires states to give voters of color an opportunity to elect their “preferred representatives.”62 But given the danger that they may act to minimize elected representation and political power for communities of color, legislators cannot go further in concentrating black voters than the VRA requires. The head of the North Carolina NAACP said that maps packing black voters into a few districts seek “to isolate black voters and destroy effective cross-racial coalitions” in voting.63

States have to balance their obligations under both VRA and the U.S. Constitution’s Equal Protection Clause, which generally prohibits district boundaries that are based on race. In 2015, the Supreme Court ruled Alabama’s district maps unconstitutional. Alabama legislators drew one district in which more than 70 percent of the voters were black—far more than was necessary to ensure black voters a fair shot at electing their preferred candidate. The Court stated that the VRA is not satisfied with “a particular numerical minority percentage” of voters of color.64 Instead, legislators must look at past voting records and local conditions to determine what percentage is required to ensure that voters of color have an equal say. A federal court identified the same problem in Virginia in 2015 when it struck down the state’s congressional map for setting a numerical goal of 55 percent black voters in some legislative districts, rather than asking how to avoid a reduction in black voters’ political power.65

The Supreme Court could continue providing clearer guidelines on unconstitutional racial gerrymandering in this term. This year’s cases from Virginia and North Carolina claim that redistricting maps pack black voters into a few districts, minimizing their influence in neighboring districts.

In McCrory v. Harris, the Court is reviewing a federal court order striking down North Carolina’s 2011 maps for packing too many black voters into two congressional districts.66 The court said, “For decades, African-Americans enjoyed tremendous success in electing their preferred candidates in former versions of [the two challenged districts], regardless of whether those districts contained a majority black voting age population.”67 The court found “an extraordinary amount of direct evidence … that shows a racial quota, or floor, of 50-percent-plus-one-person was established” for the state’s 1st Congressional District and that “this quota was used to assign voters … based on the color of their skin.”68

A federal judge recently struck down North Carolina’s state legislative districts as unconstitutional racial gerrymanders and ordered a special election in 2017.69 The court said the special election was justified by “the injury caused by allowing citizens to continue to be represented by legislators elected pursuant to a racial gerrymander.”70

The Supreme Court has made clear that map-drawers must start by asking how to maintain districts in which voters of color can elect their preferred candidates. Politicians cannot use the Voting Rights Act as an excuse to pack black voters into a few districts and make the surrounding districts whiter. The Court’s new guidelines defining illegal racial gerrymandering make it harder for politicians to manipulate maps to disenfranchise communities of color. The ongoing partisan gerrymandering lawsuits have the potential also to offer clear guidelines on how far map drawers can go in manipulating lines to benefit their political party. Many argue that the efficiency gap is exactly the kind of “judicially discernible and manageable”71 standard that the Supreme Court has not found in earlier cases challenging improper partisan gerrymanders.

Noteworthy redistricting challenges

The U.S. Supreme Court is considering two redistricting cases this term and hears oral arguments on December 5.

- North Carolina: McCrory v. Harris involves a challenge to the state’s 2011 congressional maps alleging that state GOP officials engaged in racial gerrymandering when they unfairly packed black voters into the 1st and 12th congressional districts.72 A federal court found race to be the predominant factor in drawing the two congressional districts and struck them down. There have been several other redistricting challenges to North Carolina’s maps. In 2015, the Supreme Court in Dickson v. Rucho vacated a lower court’s decision that the state legislative districts lines were constitutional after they had been challenged for improper racial gerrymandering.73 Parties have since submitted briefs to the North Carolina Supreme Court for review.74 In 2016, lawsuits were filed in federal court in North Carolina alleging that the state’s remedial congressional maps were the product of improper partisan 75 The maps were drawn to replace the state’s original maps after they were struck down by a federal court.76 North Carolina’s state legislative maps were struck down in August 2016, after a court found that the maps were a product of improper racial gerrymandering, and the same court recently ordered a special election under new maps in 2017.77

- Virginia: In Bethune-Hill v. Virginia State Board of Elections, a group of voters claimed that the Virginia General Assembly violated the rights of black voters by using a racial quota to pack voters of color into 12 of the 100 districts for the Virginia House of Delegates.78 In 2015, a three-judge panel struck down Virginia’s congressional district lines as unconstitutional for setting a racial quota.79

In the past two years, the Supreme Court has ruled on several other redistricting cases.

- Alabama: In 2015, the Supreme Court ruled against Alabama legislators who had manipulated district boundaries to keep the same percentage of black voters as in prior years, regardless of changes in population.80 The Court remanded that case, Alabama Legislative Black Caucus v. Alabama, back to the district court for further proceedings. On remand, the trial court issued an order requiring the plaintiffs to submit a new map.81

- Arizona: Also in 2015, the Supreme Court ruled in Arizona State Legislature v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission that an independent redistricting commission created by Arizona’s voters via ballot initiative back in 2000 did not violate the U.S. Constitution’s Elections Clause.

- Texas: In 2016, the Supreme Court decided Evenwel v. Abbott, unanimously upholding the long-standing practice of drawing legislative districts on the basis of total population rather than population of people who are eligible to vote.82

State and federal courts are also hearing redistricting challenges.

- Wisconsin: A case was filed in Wisconsin in early 2016, challenging the state’s GOP-drawn legislative district maps for partisan gerrymandering.83 The three-judge panel ultimately struck down the maps as unconstitutional.84 Wisconsin has now been ordered to redraw its district map twice over just a four-year period because of improper gerrymandering.

- Florida: Several suits have been filed in Florida in recent years. State courts have struck down congressional maps on the basis of racial and partisan gerrymandering.85 In another case, the state constitution’s prohibition on partisan gerrymandering was challenged as an infringement of the freedom of speech under the First Amendment.86 The suit was dismissed by a judge in 2015.87

- Maryland: In Maryland, a challenge was made to the state’s 2011 district maps, which are alleged to improperly favor Democratic candidates.88 That case will be heard before a three-judge panel.89

Redistricting maps are also challenged at the local level. For example, in 2016, a lawsuit was filed in a federal court in Georgia challenging the district maps for the Gwinnett County Board of Commissioners and Gwinnett County Public Schools Board of Education.90 The suit claims that the county’s maps dilute the strength of voters of color within the community.91 The case is currently awaiting its day in court.

Recommendations for drawing fairer election districts

To address the manipulation of maps by politicians, voters must look beyond the courtroom and demand reforms that take these decisions out of the hands of politicians. At the very least, the redistricting process must include proper constraints and clear guidance, as well as public transparency and input. Some states have set up processes that minimize the power of politicians to manipulate the districts, including establishing independent redistricting commissions, creating clear legal guidelines for drawing district maps, and opening the process up to the public.

Establish independent redistricting commissions

Several Western states use independent commissions to draw election districts using fair, neutral criteria.92 Most of these states have transparent processes, rather than politicians who operate behind closed doors.

States and local jurisdictions should follow the lead of California and establish bipartisan independent redistricting commissions responsible for drawing congressional and local district maps. Independent commissions offer several benefits, including eliminating the appearance of impropriety and making elections fairer. Legislators, for instance, are four times more likely than independent commissions to create congressional districts that “deny voters choices in the primary” and two times more likely to do so for general elections.93 This is perhaps one of the reasons why maps drawn by independent commissions face fewer legal challenges than maps drawn by politicians.94

There are different ways to design independent or citizen-led redistricting commissions. These commissions should be comprised of an equal number of members associated with each major party, ensuring that at least one member from the opposing party must vote for any plan before it is implemented.95 Missouri and Idaho, for example, require that an even number of commissioners are appointed from each party. Missouri goes so far to require a supermajority to approve any final redistricting plan to ensure that all views are considered.96 Alternatively, an independent commission could be comprised of an equal number of members from each major party, plus one tiebreaker who is appointed by the judiciary and not registered with either of the major parties.97

In addition to partisan diversity, members of any independent commission should be representative of demographic differences to ensure that the commission is representative of the populations in the districts it is responsible for drawing. Jurisdictions may require that one or more commissioners be chosen from each region, while others may require that a commission “reflect the racial ethnic, geographic, and gender diversity of the state.”98

In California,99 a panel of state auditors chooses 20 potential commissioners—with an even number of Republicans, Democrats, and independents.100 Legislators from both parties can each remove two of the 20 names.101 Of the remaining 16, the first eight commissioners are chosen at random, though it must include three Democrats, three Republicans, and two independents.102 The eight commissioners then appoint the remaining six, with equal numbers from all three groups.103 A district map must be approved by nine of the commission’s 14 members, and the approving members must include three members from both parties and three independent members.104 The maps can even be overturned by voters.105

At the local level in California, Sacramento and Berkeley residents recently approved ballot measures that establish independent redistricting commissions for drawing local city council maps beginning after the 2020 Census.106 The new Sacramento Independent Redistricting Commission will be composed of 13 members, “one from each of the eight council districts, picked by a screening panel and the other five by the chosen eight.”107 The panel will have exclusive power to draw district lines.108 Similar to Sacramento, Berkeley’s new independent commission will be comprised of 13 members, all of whom must apply for the position and must be registered city voters.109 The city clerk will select members every 10 years after each new census.110 In order to protect the commission’s independence, current and former city council members are prohibited from serving. Both measures are aimed at taking map-drawing power out of the hands of those who are elected through them.111

Arizona voters also approved a state constitutional amendment to take authority over drawing districts from politicians and put it into the hands of an independent, bipartisan commission.112 Arizona politicians sued to have the amendment overturned, but the U.S. Supreme Court rejected their argument.113 Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s opinion discussed the history of the amendment and noted, “Redistricting plans adopted by the Arizona Legislature sparked controversy in every redistricting cycle since the 1970’s.”114 Justice Ginsburg also noted studies showing that “nonpartisan and bipartisan commissions generally draw their maps in a timely fashion and create districts both more competitive and more likely to survive legal challenge.”115

Ensure clear redistricting criteria

If elected officials are tasked with drawing district lines, there must be clear criteria by which they must abide. These criteria should be established under law either through individual redistricting statutes or by including them in the state constitution, as was done in Florida. They must set out the basic principles of redistricting, namely creating fair and neutral district schemes by prohibiting manipulation to achieve partisan goals. The criteria should include barring consideration of party affiliation and voting records and maintaining communities of interest and neighborhoods when possible. By doing so, much of the improper political maneuvering can be taken out of the process. In addition, there should be a clear standard against which voters can hold elected official accountable for the maps that they draw.

Some state constitutions also outline the criteria that legislators must follow when drawing election districts.116 Most constitutions require that districts be compact and try to respect political boundaries, such as counties and cities.117 Other state constitutions have been amended to prohibit partisan goals or to require neutral, fair criteria for drawing maps.118

The Florida Constitution, for example, was amended to say that districts “may not be drawn to favor or disfavor an incumbent or political party.”119 The Florida Supreme Court ruled in 2015 that the state legislature’s 2011 map violated this requirement, and it noted that legislators drew the maps in a secret process to maximize benefit to the legislature’s Republican majority:

The Legislature itself proclaimed that it would conduct the most open and transparent redistricting process in the history of the state, and then made important decisions, affecting numerous districts in the enacted map, outside the purview of public scrutiny.120

The court ruled that “the redistricting process and resulting map were taint[ed] by unconstitutional intent to favor the Republican Party and incumbents” and ordered a new map.121

Require transparency and public input

Regardless of whether a jurisdiction’s maps are drawn by an independent commission or by elected officials, transparency and public input is important. The public should be an integral part of the process—for example, through public hearings on proposed district plans or by allowing voters to submit their own proposed plans. At minimum, proposed maps should be published online and in local newspapers for the public to review and analyze prior to implementation. Those responsible for drawing district maps may also be required to justify, on the record, the reasons they drew the lines in the way that they did.122 While most members of the public are not experts in the process of redistricting, they are perhaps best positioned to “know more about the effect of certain district configurations on local communities than legislators or commissioners” as they are the ones most directly affected by such plans.123

Of course, allowing opportunity for public comment and public hearings over proposed maps requires additional time that would perhaps not otherwise be needed if maps were simply pushed through the legislature by a controlling party. However, allowing such participation is important and necessary in ensuring that redistricting maps are fair and fully representative of the people they encompass.

Conclusion

In many places, elected officials are still in charge of drawing the electoral maps that get them elected. These officials should have the best interests of voters in mind when they draw district maps. But much of the time, elected officials are more interested in making sure they get re-elected or that their party remains in power, often at the expense of voter preferences.

Reform is needed in the redistricting process. Current cases being heard by the Supreme Court may help lead the way by more clearly defining what drawers of district maps can take into account when creating them and to what extent. At the state and local level, however, jurisdictions must act to make the redistricting process fairer and more transparent. They can start by establishing independent redistricting commissions or by passing laws that clearly establish criteria and rules that map drawers must abide by in creating district maps. Jurisdictions must also open the process up to the public and encourage public input and participation. In this way, voters can receive the fair representation to which they are entitled.

About the authors

Liz Kennedy is the Director of Democracy and Government Reform at the Center for American Progress.

Billy Corriher is the Director of Research for Legal Progress at the Center.

Danielle Root is the Center’s Voting Rights Manager.