Over the past few years, and in particular over the past few months, the number of children and families leaving the Central American countries of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras and arriving in neighboring countries and at our southern border has grown significantly. Already in fiscal year 2014, more than 57,000 children have arrived in the United States, double the number who made it to the U.S. southern border in FY 2013. The number of families arriving at the border, consisting mostly of mothers with infants and toddlers, has increased in similar proportions. In fiscal year 2013, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, or DHS, apprehended fewer than 10,000 families per year; yet, more than 55,000 families were apprehended in the first nine months of fiscal year 2014 alone.

The majority of unaccompanied children and families who are arriving come from a region of Central America known as the “Northern Triangle,” where high rates of violence and homicide have prevailed in recent years and economic opportunity is increasingly hard to come by. Officials believe a total of at least 90,000 children will arrive on the U.S.-Mexico border by the end of this fiscal year in September.

This brief aims to shed light on this complex situation by putting the numbers of people leaving the Northern Triangle into context; analyzing the broad host of drivers in Central America that have caused a significant uptick in children leaving their countries; and prescribing a series of foreign policy steps to facilitate management of this crisis and also to address the long-term root causes pushing these children to flee their home countries. This brief, however, does not delve into the needed domestic policy changes in the areas of immigration and refugee law.

Changed flows in persons arriving from Central America

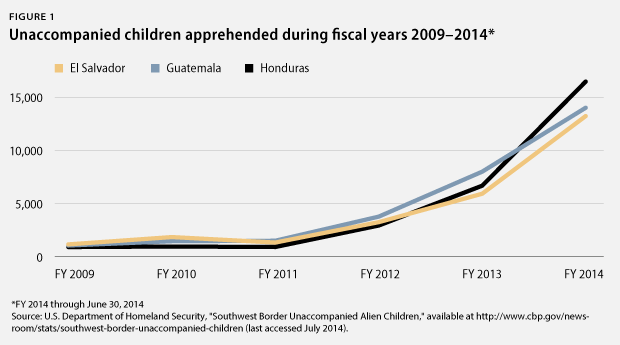

While the media did not focus until recently on the issue of rapidly rising numbers of unaccompanied children and families crossing the southern border, this trend has not been an overnight phenomenon. Before FY 2011, U.S. Customs and Border Protection officers encountered an average of 8,000 unaccompanied children on an annual basis. The majority of these children came from Mexico, with fewer coming from El Salvador and Guatemala and even fewer from Honduras. This trend shifted in 2011, when three times more children from Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador arrived at the U.S. border, with the majority coming from Guatemala. The following year, their numbers doubled again, totaling more than 20,000 unaccompanied children in FY 2012 and for the first time eclipsing the number of Mexican unaccompanied children crossing the border. Already this fiscal year, more than 57,000 children have arrived alone at the U.S. southern border, and a total of at least 90,000 children are expected to arrive on the border by the end of the year. Some estimates have predicted that as many as 220,000 unaccompanied children could arrive in FY 2015.

In examining the current dynamic, it is essential to understand that the United States is not alone in experiencing a significant influx of persons coming from Northern Triangle countries. According to the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees, or UNHCR, Salvadoran, Guatemalan, and Honduran children and families are also seeking refuge closer to home in the neighboring countries of Mexico, Panama, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Belize. In 2012, these five countries registered an astounding 432 percent increase in the number of asylum requests compared to the number of similar requests lodged in 2009 by individuals from the Northern Triangle countries. In 2013, the number of people from the Northern Triangle seeking asylum in neighboring countries jumped 712 percent from 2008 levels. People are also seeking safe haven within their own countries, as evidenced by rising numbers of internally displaced persons, especially in Honduras and Guatemala. For example, 17,000 Hondurans have become internally displaced since 2008, according to civil society monitors, mostly due to criminal violence perpetrated by local gangs and transnational drug trafficking organizations.

There are less data about the number of families fleeing, but according to the Women’s Refugee Commission, the number of families arriving at the U.S. border has increased in similar proportions to the number of unaccompanied children. In fiscal year 2013, DHS apprehended fewer than 10,000 families per year; yet, more than 55,000 families were apprehended in the first nine months of fiscal year 2014 alone.

Not only have the numbers of persons coming to the United States from this region changed over the past few years, but the demographic composition of these new arrivals has changed as well. For years, it was more common to see older teens, almost always male, coming to the United States. Today, children ages 12 and under are the fastest growing group of children arriving alone at the border, and almost half the children coming are girls. Just a few years ago, it was rare for a child younger than 12 years old to arrive alone in the United States. Today, it is commonplace for elementary-school-aged children to be apprehended by U.S. Customs and Border Protection on the southern border.

Factors behind the rise in unaccompanied children

Some in Congress have been quick to try to score political points by accusing the Obama administration of having brought on this influx of children and families. The first congressional hearing on the issue was tellingly named “An Administration Made Disaster: The South Texas Border Surge of Unaccompanied Alien Minors.” At the hearing, House Republicans argued that lax border enforcement and the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA, program—which grants a two-year reprieve from deportation and a work permit to eligible undocumented youth—has given children in Central America an incentive to come to the United States. Rep. Darrell Issa (R-CA) even called on President Barack Obama to end DACA and to begin deporting those with the temporary legal status in order to send a message to prospective child refugees that they should not come to the United States.

Contrary to what the administration’s opponents may claim, however, it is clear that U.S. border enforcement policies are not the primary drivers of children coming to the United States. Instead, much of the surge stems from the interrelated challenges of organized criminal violence and poverty that adversely affect individuals in Northern Triangle countries.

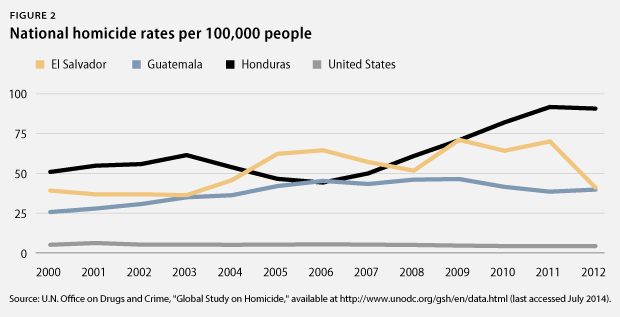

Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador were three of the five most dangerous countries in the world in 2013. The U.N. Office on Drugs and Crime, or UNODC, found that Honduras had the world’s highest per-capita homicide rate in 2012, at 90.4 homicides per 100,000 people. El Salvador was fourth in the world, with a rate of 41.2 homicides per 100,000 people, and Guatemala was fifth, with a rate of 39.9 homicides per 100,000 people. To put these numbers into context, consider that the war-ravaged Democratic Republic of the Congo, from which nearly half a million refugees have fled, has a homicide rate of 28.3 homicides per 100,000 people. By contrast, other countries in Central America—such as Costa Rica, at 8.5 homicides per 100,000 people; Nicaragua, at 11.3 homicides per 100,000 people; and Panama, at 17.2 homicides per 100,000 people—all have significantly lower rates of homicide. These safety differentials help to explain why some from the Northern Triangle countries are fleeing to neighboring countries. The only notable exception is Belize, which has a homicide rate of 44.7 homicides per 100,000 people but has not experienced significant changes in migration patterns.

Although each country in the Northern Triangle has experienced different relative ebbs and flows in violence during the past few years, levels of crime and violence have intensified. In Guatemala, a brief downward trend in homicides from a peak in 2009 reversed course in 2012 and continued to rise in 2013. In El Salvador, a gang truce that reduced homicides by nearly half from March 2012 to March 2013 has unraveled, and violence has spiked to a level of 70 homicides per 100,000 residents in recent months. In Honduras, homicides have dramatically increased in the past five years from 50 homicides per 100,000 people in 2007 to 90.4 homicides per 100,000 people in 2012.

A DHS study confirms that most children leaving the Northern Triangle countries are doing so because of regional violence and poverty. The study looks at the specific localities that children apprehended at the U.S. border call home. San Pedro Sula, Tegucigalpa, and Juticalpa in Honduras and San Salvador in El Salvador were the major cities and towns where the children were from. Not surprisingly, these four cities are among the poorest and most violent in the region. San Pedro Sula, for instance, with a rate of 187 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants in 2013, has the highest murder rate of any city in the world and sent 2,000 children to the United States in the first five months of 2014.

Interviews performed by UNHCR staff confirm that while the reasons for these children fleeing are complex and multifaceted, violence is a primary motivating factor. Of the 404 children interviewed by UNHCR who came from Northern Triangle countries and arrived in the United States after October 2011, 48 percent shared that they had been personally affected by the rise in violence in the region brought about by organized armed criminals. The same survey found that at least 58 percent of these children had been “forcibly displaced because they suffered or faced harms that indicated a potential or actual need for international protection.” Another survey of Salvadorian children who had fled their home country and were returned to El Salvador from Mexico had similar findings: 61 percent listed crime, gang threats, and insecurity as reasons for leaving. Interviews conducted by the Refugee and Immigrant Center for Education and Legal Services, or RAICES, of 925 children housed at the Lackland Airforce Base in Texas in recent weeks found that 63 percent were eligible for relief from deportation by a U.S. immigration judge, meaning that nearly two-thirds of those interviewed were victims of sexual assault, trafficking, domestic abuse, gang intimidation, persecution, or torture.

Much of this crime and violence stems from the diversification of criminal activities by transnational gangs and other transnational criminal organizations, or TCOs. In Latin America, fully 30 percent of homicides in 2013 were organized-crime- or gang-related compared to just 1 percent in Asia, Europe, and Oceania. Although estimated gang membership in each of the Northern Triangle countries varies, even low estimates from UNODC suggest that gang membership has reached epidemic proportions. In El Salvador, for example, UNODC estimated that there were 323 gang members per 100,000 residents in 2012, for a total of approximately 20,000 gang members. UNODC estimated overall gang membership in Guatemala at 22,000 people and in Honduras at 36,000 people. That means there are more gang members than police in both El Salvador and Honduras. El Salvador, for example, has a police force of 16,000 individuals, and Honduras has a force of fewer than 15,000 police personnel. Testifying before Congress in 2012, Ambassador William Brownfield, assistant secretary of state for international narcotics and law enforcement affairs, estimated there were a total of 85,000 gang members in the Northern Triangle countries combined.

Northern Central America has proven to be particularly fertile ground for gangs and TCOs because of the underlying economic despair faced by too many people in these societies. The most recent economic development data underscore the economic plight in much of the Northern Triangle. More than 13.5 percent of Salvadorans live in extreme poverty and more than 45 percent live in poverty. The figures are even worse in Guatemala, where 29.1 percent of the people live in extreme poverty and 54.8 percent live in poverty, and in Honduras, where 42.8 percent live in extreme poverty and 67.4 percent live in poverty. In addition to stifling levels of poverty, the Northern Triangle countries are among the world’s most economically unequal. Based on latest available data, Honduras and Guatemala rank among the lowest 12 countries in the world in terms of their Gini coefficients, which measure income and consumption disparity, while El Salvador is number 30. The rankings place the Northern Triangle countries among countries throughout sub-Saharan Africa and the poorest in Latin America and the Caribbean, such as Angola, the Central African Republic, South Africa, Haiti, and Zambia.

Creating safer conditions in Central America

Stemming the tide of unaccompanied children arriving in the United States and neighboring countries will require both short- and long-term solutions, both in the United States and in the Northern Triangle countries. While there are no silver bullet solutions to the problem, any and all recommendations must take into account the needs of the children at the heart of this crisis.

Recommendations for Northern Triangle states

If the countries of the Northern Triangle are to create conditions in which their youth face something other than the impossible choice of engaging in criminal activity or attempting a perilous migration to the United States, the necessary turnaround must be rooted in Central America itself and consist of a whole-society approach to address criminal violence and poverty. That is to say: The countries of the Northern Triangle need more-effective governing institutions and greater contribution from all levels of society throughout the region, including the private sector, to create sustainable security and economic environments.

Create and support robust state security institutions

On the security front, the countries of the Northern Triangle lack the professional police forces, credible judiciaries, and effective penal institutions needed to protect their citizens from burgeoning criminal gangs. International actors, including the United States, can and should assist in the creation of these institutions, but all the assistance in the world will not succeed absent a whole-society commitment to building and sustaining those institutions.

Such a commitment has been missing far too often across the Northern Triangle, as the elites in these countries have opted for a go-it-alone approach rather than aligning with the government to improve basic security conditions for all. In Guatemala, for example, private security forces outnumber public security forces by at least 4-to-1. An obvious first step in reversing this self-destructive trend is to redirect those expenditures on private security forces to provide the state with the resources necessary to build robust institutions and drastically increase public safety.

Although it is easy to over simplify the lessons learned from the Americas’ most striking recent success story, Colombia provides an instructive example for others in the region, with its rapid transformation from a near-failed state in the late 1990s to today being on the verge of becoming only the third Latin American country in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, or OECD, a group of the world’s most economically developed countries. That incredible transition illustrates the value of aligning the private sector and the state. In large measure, Colombia’s advances in security and economic development, which admittedly remain a work in progress, came after Colombia’s private sector largely abandoned a go-it-alone security approach in favor of supporting robust state security institutions by paying what was known as a “war tax.” That is, Colombia’s elites agreed to pay more in taxes to the central government to fund its security efforts. Similarly, the turnaround of Medellín, Colombia, from the “murder capital of the world” to “Latin America’s most innovative city”—according to Citi Bank, WSJ. Magazine, and the Urban Land Institute—was partly fueled by the public, private, and civic sectors coming together to build a safer, more sustainable community. Rather than maintaining the kind of adversarial relationship that is too common in the Northern Triangle among government, economic, and civic leaders, those groups decided to work together to build a better future for Medellín, particularly its most marginalized communities.

In contrast, efforts to push fiscal reforms in the Northern Triangle to provide more tax revenue for security efforts and social programs have been met with tremendous resistance from a private sector that refuses to provide additional resources to the state. Honduras’ most recent fiscal reform, which raised taxes on the nation’s economic elites, only occurred at the last minute to avoid the country’s collapse in the face of mounting public debt and was timed to allow the then-incoming president to avoid raising taxes during his current term. In El Salvador, recently elected President Salvador Sánchez Cerén turned to fiscal reform as a priority in the early days of his administration and has been met with immediate private-sector resistance. In Guatemala, despite a commitment—pledged in the 1996 peace accords that ended Guatemala’s 36-year civil war—to raise tax revenues as a percentage of gross domestic product, or GDP, from 8 percent to 12 percent by 2000, the first meaningful fiscal reform did not occur until 2012, when Guatemala’s tax collection as a percentage of GDP stood at a measly 10.9 percent.

Stronger institutions, beginning with more-robust rule-of-law institutions, are also essential to the long-term economic sustainability of the countries of the Northern Triangle. The protection of a full host of rights—consumer, property, intellectual, and commercial, to name only a few—is a key component to the functioning of sustainable and equitable market economies. Those protections require effective and independent courts—not just criminal courts, but also civil courts. The creation of such courts is impossible without a whole-society commitment.

So, too, is bolstering the institutions that are responsible for providing basic government services, including health and education. Without robust social services, rule-of-law and other security institutions cannot and will not deliver desired results, nor is sustainable economic development achievable.

Building these kinds of institutions will take time, and although that work needs to intensify immediately, the private sector need not sit idly by while supporting fiscal and institutional reforms. The private sector in each of these countries could do far more through direct involvement and contribution to create economic opportunities and improve the basic security environment for their fellow citizens.

Nowhere is the chasm between private-sector neglect of overall living conditions and the desperation of those living conditions leading children to seek refuge elsewhere more prominent than in the cradle of the Honduran private sector—San Pedro Sula. A disproportionate number of children arriving in the United States from Honduras are from San Pedro Sula, which has long been Honduras’ business capital and today is its murder capital as well. Despite that reality, there is scant evidence of the Honduran private sector reaching out to its own communities to fund crime and violence prevention programs, which have been shown to work but require a combination of public and private resources to be brought to scale.

Enhance accountability of judiciary and police forces

In addition to enhanced resources, institution building across the Northern Triangle requires greater across-the-board accountability. Increased accountability means more-effective vetting of police, judges, and prison guards, both throughout selection and training and on the job. It also means rooting out the corruption that is endemic in business and politics in this region. Fighting corruption is key to restoring faith in government institutions, which is perilously low throughout the Northern Triangle. In fact, the residents of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras rank last among Latin American populaces when it comes to believing their respective governments can both adequately address crime and solve the problem of corruption.

International efforts such as the International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala, or CICIG, can be part of the anti-corruption and anti-impunity solution, but changed societal and institutional practices are the keys to meaningful reform. That means bolstering—and in many cases, creating—courts that protect the rights of all individuals, not just those of the wealthy few. It also means respect for the separation of powers so each branch of government can hold the others accountable.

Enhanced accountability must also be a feature of the international cooperation needed to confront the TCOs behind much of the human trafficking that is fueling the current dynamic.

Foster regional cooperation

Political leaders in the Northern Triangle also need to set aside national rivalries and distrust to focus on cross-border cooperation. Too often governments in Central America pay lip service to the primacy of regional cooperation while privately championing bilateral assistance flows—over which they can exercise more individual control—from the United States and other international donors. Reducing the threat posed by transnational criminal organizations, however, requires transnational responses.

To cite one example, Honduras’ insistence on investing in fighter aircraft and radar—likely rooted in its historical distrust of and territorial disputes with its neighbor El Salvador—at the expense of other security efforts makes little sense against the common threat posed by TCOs, as 85 percent of the drug flow into Central America comes from the maritime domain. If the countries of the Northern Triangle are to prosper, they must do so together instead of with an eye of suspicion toward one another.

Recommendations for U.S. assistance to the region

Against this backdrop, there are concrete steps the United States can and should take to fulfill its shared responsibility to confront the underlying security and economic conditions in the countries of the Northern Triangle.

Encourage a whole-society approach

In its programs, policies, and public diplomacy, the United States government should encourage political, civic, and economic actors across the Northern Triangle to set aside political and ideological differences in order to reach national compacts that address core economic development and security needs.

With the 2011 launch of Partnership for Growth, or PFG, with El Salvador, the Obama administration embarked, albeit at a smaller scale, on precisely such an effort. Although imperfect, the PFG model forced greater coordination and cooperation among U.S. government departments and agencies, but equally as importantly, it helped foster greater cooperation between the government of El Salvador and the country’s key economic actors. Fostering those ties remains very much a work in progress—one requiring mutual commitment from the government and the private sector. Such efforts need to be supported in El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala; medium- to long-term success on economic development and citizen security demand it.

Enhance international accountability

This week, President Obama and Vice President Joe Biden will host President Otto Pérez Molina of Guatemala, President Sánchez Cerén of El Salvador, and President Juan Orlando Hernández of Honduras in Washington. On June 20, Vice President Biden met with Presidents Pérez Molina and Sánchez Cerén, as well as senior representatives from the Honduran and Mexican governments. Such meetings are essential to galvanize action from each of the governments at the table and to hold political leaders accountable for past commitments.

Vice President Biden’s personal diplomacy has been a linchpin in the Obama administration’s second-term approach to Latin America and the Caribbean. His continued and regular collective engagement—perhaps as often as once every four months initially—with leaders from these countries is essential to sustain the high-level commitment needed to tackle the structural challenges that stand in the way of a long-term solution to this migration crisis.

Another key element to enhancing international cooperation is ensuring that the United States is adequately represented in the countries at the heart of this humanitarian crisis and at the Inter-American Development Bank, or IDB—an institution capable of leveraging U.S. development dollars into broader investments in the Northern Triangle. Nominations for a new U.S. ambassador to Guatemala and for a new U.S. executive director of the IDB are pending before the Senate. Action on those nominations is a cost-free way to strengthen the U.S. response to this crisis and reinforce the hard diplomatic and development work needed to foster medium- and long-term solutions.

The IDB, the administration, and Congress must also work together to expeditiously achieve adequate governance reforms at the IDB so the United States can complete its contribution to enhancing the bank’s lending capacity. The IDB is a key source of multilateral development funding for the countries of the Northern Triangle and a key multiplier of U.S. development resources. Without its principal shareholder—the United States—meeting its capital commitments, it will be extremely difficult to maximize the IDB’s contribution to the medium- and long-term development work needed in Central America.

Increase U.S. investment in development and citizen security

In recent weeks, the Obama administration has announced a series of new and prospective investments in citizen security and economic development initiatives in the Northern Triangle.

The administration’s emergency supplemental appropriations request includes $300 million that “would support efforts to repatriate and reintegrate migrants in Central America, to help governments in the region better control their borders, and to address the root causes driving migration.”

As part of Vice President Biden’s meeting with leaders from Mexico and the Northern Triangle, the administration announced additional immediate-term resources, as well as additional investments in development and citizen-security projects, in Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras.

In the case of Guatemala, for example, the U.S. Agency for International Development has announced a new $40 million five-year citizen-security program. In El Salvador, the administration is initiating a $25 million five-year citizen-security program aimed at reducing and preventing crime in addition to existing citizen-security efforts. In Honduras, the administration will provide an additional $18.5 million to support community policing. The administration also announced nearly $10 million in new funding to enhance the capacity of each of these countries to receive and reintegrate repatriated migrants.

These additional resources—both the reprogramming of existing resources and the supplemental appropriations request—are steps in the right direction. They will, for example, enhance the capabilities of each of these countries to deal with the immediate needs of repatriated children. They will also help bolster the consular capabilities of each of these three countries in the United States, a step that should ease administrative burdens associated with processing arriving unaccompanied children.

What is needed now, however, is a longer-term commitment to enhanced funding streams for development and citizen-security efforts in El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. Although the Obama administration has more than doubled annual citizen-security funding for Central America compared to 2008 levels, funding for economic development in particular has been under significant pressure. That trend needs to be reversed as U.S. resources can help bring to scale proven violence-reduction pilot programs and economic development projects across the Northern Triangle. Doing so will require more than the administration’s initial $300 million request.

Leverage trilateral cooperation with Colombia and Mexico

An effective mechanism for stretching security-related investments in particular is to build on the administration’s efforts to leverage security cooperation with Colombia and Mexico to benefit countries in the Northern Triangle. In the past nearly decade and a half, the United States has invested more than $8 billion in enhancing Colombia’s security capabilities—while Colombia invested many times of that amount. As a result, there is a robust security-related infrastructure in Colombia that has been, and can further be, leveraged to benefit countries in Central America. To a lesser scale, recent U.S. investment in Mexican security institutions has created relationships and capabilities that must continue to be leveraged to confront the TCOs at the heart of the current dynamics.

Trilateral cooperation is one way to encourage greater Latin American support for the countries and the people of the Northern Triangle. Engagement by countries throughout the Americas, however, should not rely solely on cajoling from or cooperation with the United States. Countries, such as Brazil, that aspire to greater hemispheric leadership and global prominence and have the resources to help should step up. Brazil was quick to involve itself in the politics of Honduras during the fallout from the country’s June 2009 coup, but Brazil has done little to involve itself in advancing economic development and citizen security in Honduras since. That should change.

Enhance transnational criminal organization targeting

The Obama administration issued a national strategy for countering transnational organized crime in July 2011. That new strategy made available a range of tools to be used against TCOs that adversely affect the national security interests of the United States. At the time the strategy was issued, a handful of TCOs were designated for, among other measures, targeted financial sanctions.

Initially, only Los Zetas—Mexico’s most violent and notorious drug cartel—was designated in the Western Hemisphere. The Central American gang Mara Salvatrucha, or MS-13, was subsequently added. The time has come to designate additional criminal organizations that are responsible for the wide-scale human trafficking in evidence today. Turning designations into realities, of course, requires resources. A linchpin in such targeting efforts is the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control, or OFAC. Given the press of sanctions work relating to Russia, Iran, Syria, Ukraine, Sudan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and other global flashpoints, OFAC is overburdened and needs more resources. Absent such additional resources, however, steps should be taken—at least temporarily—to redirect OFAC’s Western Hemisphere resources toward cracking down on human traffickers who prey on despair in the Northern Triangle, even if it means fewer resources dedicated to enforcing Cuba-related sanctions or to targeting drug cartels elsewhere in the region.

Limit military involvement

In the midst of a crisis, especially one fueled by nefarious networks such as the human and drug traffickers at the center of recent migration spikes, there is a strong temptation to pull out every tool in the government’s tool box, including modified versions of those developed by the U.S. military elsewhere in the world to take apart networked threats. Although there is a role for military-to-military cooperation in bolstering citizen security in the Northern Triangle, that role must remain decidedly limited—even though the strongest, most professional security institutions in the Northern Triangle are the countries’ militaries. Although those forces have been, and will continue to be, deployed in policing functions, the U.S. government needs to be very careful not to feed that dynamic any more than is absolutely necessary.

Reducing crime and violence in Central America is not something that can ultimately be achieved by forces trained to defend the territorial integrity of their respective countries. It is not what militaries do, nor should it be something they are encouraged to do. As discussed previously, more effective rule-of-law institutions—police, courts, and prisons—coupled with sustainable economic development are the keys to success. Investing in militaries or modeling behavior that suggests militaries can solve these problems, similar to the U.S. military efforts to dismantle insurgent and terrorist networks elsewhere in the world, does not advance sustainable solutions.

Conclusion

The rise in unaccompanied children arriving at our southern border has prompted many to conclude that the causes and solutions to the challenge are largely—or even solely—in the United States.

Although there is plenty that the United States can and should do to address this challenge in a humane manner, its root causes in Central America must be understood and mitigated before this challenge can ultimately be solved. That work is only possible with a whole-society commitment in the Northern Triangle countries. Only with a unified commitment from political, economic, and civic leaders in El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras to address citizen security and economic development in an integrated way can the United States effectively support the governmental and nongovernmental partners needed to achieve short-, medium-, and long-term success.

Dan Restrepo is a Senior Fellow at the Center for American Progress. Ann Garcia is a Policy Analyst for the Immigration Policy team at American Progress.