This Friday, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) will release employment data for March amid increased tension and attention surrounding employment releases. Although job growth has continued over the past year, other measures of the U.S. economy have slowed significantly, particularly since December 2018. Markets and commentators have focused on the possibility that a yield curve inversion—a scenario in which investors demand a higher interest rate for short-term loans than longer-term loans—indicates that the economy could tip into a recession. There is mounting evidence that the economy has slowed down, but so far this sluggishness has resembled a slowing of growth globally and domestically following an ill-timed tax cut rather than the beginning of a recession. Watched closely, this month’s report should either reveal signs of continued strength or more rapid slowing of job and wage growth. Beyond the short-term focus on a possible recession, it’s important to maintain perspective, as other indicators suggest that there remains much to improve on and strive for to ensure and maintain economic growth for all.

Persistent wealth and income gaps as well as the housing affordability crisis prevent many groups from accessing the resources they need to thrive in the U.S. economy. Economic realities—including the changing demographics of the labor force in terms of both age and race and ethnicity as well as occupational differences compared with decades prior—highlight the need to explore the nuances of broad economic indicators. Yet, despite inheriting an economy that is finally beginning to recuperate from the Great Recession, President Donald Trump continues to tout his economic successes for American workers on the back of an “explosive Stock Market” and recent tax cuts. Reality, however, paints a different picture.

Stagnant wages, sectoral employment, and the need for economic security

Forty percent of Americans are unable to cover a $400 emergency expense, and wages have remained close to stagnant for most people, despite gains for top earners. An analysis from the Economic Policy Institute shows that labor income for the bottom 90 percent of Americans has shrunk by more than 10 percent since 1979—translating to about $10,800 of total lost wages per household. All the while, costs of living—including child care and education costs—have continued to rise, outpacing wage growth for most Americans. With little sign of bipartisan cooperation on pro-worker policies, a tight labor market is the primary area in which most workers can expect to reverse this trend in the coming year.

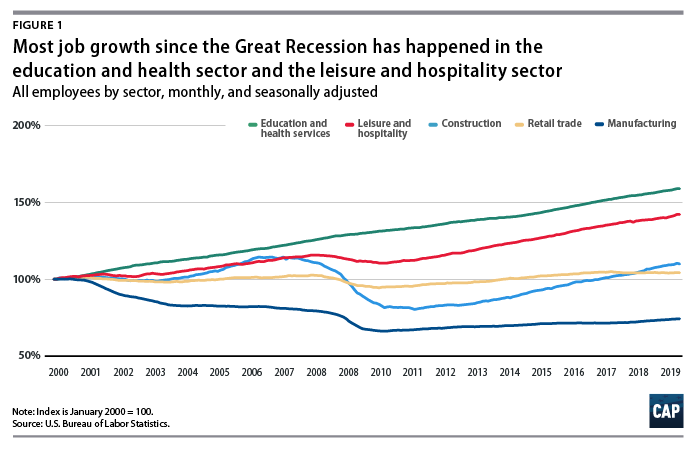

Broader economic trends that put pressure on American workers—in conjunction with the Trump administration’s disconcerting priorities that favor the wealthy and corporations—hurt working families. They also put into focus the need to highlight the conditions and lived experiences of people across the economy. Job growth has been uneven across all sectors of employment since the Great Recession, with many sectors only now returning to their prerecession employment levels. The food service and health care sectors—which tend to have lower-than-average hourly earnings—have seen the most job growth since the recession.

As seen in Figure 1, job growth within the education and health services sector has steadily surpassed 2000 levels, accounting for a large portion of overall employment growth. Job growth within the leisure and hospitality sector, while less constant throughout the recession, has also substantially increased in recent years. Meanwhile, manufacturing—a sector that tends toward higher-than-average hourly earnings—continues to consist of a small share of overall employment growth.

Unemployment

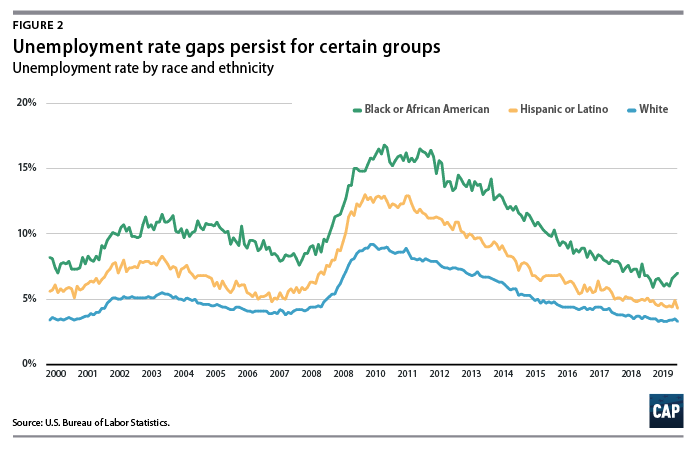

The gains from the economic recovery have not been experienced equally among different demographics, and groups with historically worse labor market conditions continue to face higher unemployment rates, which lead to long-term detrimental effects such as lower lifetime earnings and future homeownership rates. The overall unemployment rate fell from 10 percent to 3.8 percent between the peak of the crisis in October 2009 and February 2019, the latest month for which data are available. While the unemployment rate for blacks or African Americans dropped from 15.8 percent to 7 percent during the same time frame, there is still a significant employment gap. Younger people also face disproportionately high unemployment rates, with black or African American youth suffering from unemployment rates that are more than four times that of the overall population.

According to the latest data available, the black or African American unemployment rate remains more than double the unemployment rate for whites, at rates of 7 percent and 3.3 percent, respectively. For Hispanics and Latinos, the gap is smaller but persists.

U-3 vs. U-6

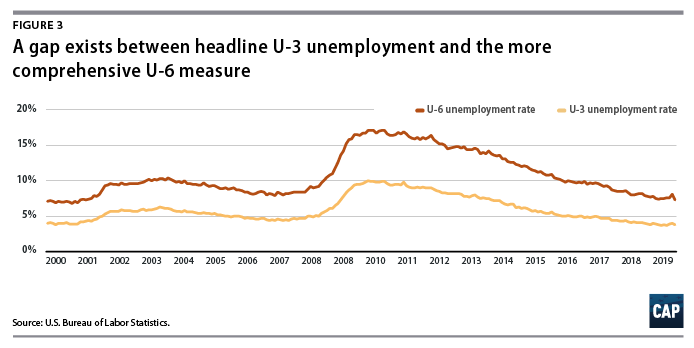

The headline unemployment rate, otherwise known as U-3, is the most frequently cited indicator of labor market health, but it can underestimate the number of people who are unable to find jobs. For example, it does not capture individuals who want jobs but have given up looking for work or those who would like full-time work but can only find part-time positions. The U-6 rate, which is perhaps the most comprehensive unemployment measure, alleviates this problem by including marginally attached workers—those who have recently looked for work but who are not currently looking—and part-time workers who would prefer full-time work. A low U-6 rate indicates that people who face greater barriers to finding employment are being pulled back into the labor market due to greater economic opportunity. The U-6 rate is always higher than the U-3 rate, but the gap grew much larger than usual during the recession and has remained above or near prerecession levels over the course of the recovery.

Last month, for example, the U-6 rate was 7.3 percent, 3.5 percentage points higher than the overall unemployment rate; this gap continues to slowly inch toward prerecession levels.

Focusing on the groups whose unemployment rates continue to have room for improvement should be a benchmark for the health of the U.S. labor market overall. Expanding opportunities in the labor market for these groups can be a source of future economic growth for all.

Conclusion

Friday’s employment data will provide an updated snapshot of the U.S. economy and labor market performance. Although the headline economic indicators are important, it is essential to focus on unemployment gaps as well as trends in sectoral employment growth to fully assess the health of the economy. It is crucial to understand the economic outcomes that exist across different sectors and different demographic groups. Although the economy is doing well in the aggregate, more work needs to be done to bring individuals back into the labor market. Policymakers and economists need to consider these challenges—as well as populations that face high labor market barriers—when evaluating the health of the labor market and implementing policies that affect it.

Galen Hendricks and Daniella Zessoules are special assistants for Economic Policy at the Center for American Progress. Michael Madowitz is an economist at the Center.