Introduction and summary

Lexington and Madison—rural Nebraska towns of 10,090 and 2,634 residents, respectively—are now enjoying the fruits of three decades of demographic transformation that has simultaneously advanced and challenged their communities. The two towns had a combined foreign-born adult population of just 124 in the 1990 census. Today, three decades after the opening of meatpacking plants in both communities, nearly half of Lexington’s adult population was born outside the United States, as was one-third of the adult population of Madison. Newcomers, hailing from all corners of the world, accounted for 100 percent of both towns’ population growth from 1990 to 2016.1

This report looks beyond the numbers to understand how Lexington and Madison—communities selected for study based on their rurality,2 rapid demographic change, and resulting resilience—have adapted to newcomers. Informed by conversations with more than 70 stakeholders in local government, education, faith, business, and nonprofit and civic organizations, along with lifelong residents and newcomers, this report tells the story of change and the successful management of that change in both towns.3 It explores the effectiveness of intentional strategies taken by key institutions, the successes and decentralized efforts of dedicated civic leaders, and the power of unique characteristics innate to small towns.

The two towns today boast revitalized business districts, booming housing markets, successful schools, and sustainable population growth. They offer a road map for other small, rural communities at the beginning stages of managing demographic change:

- Embrace innate advantages. In welcoming newcomers, small towns have innate advantages—intimacy, efficiency, and familiarity—that their big-city counterparts lack.

- Emphasize shared values. Focusing on common core values helps bridge other language or cultural differences.

- Partner with the private sector. Public-private partnerships can be a lifeline when the rate of demographic change outpaces a community’s ability to keep up.

- Govern consistently. The most effective inclusion efforts are designed to benefit all community members—not just newcomers or longtime residents specifically.

- Build leadership pipelines. Investments in the next generation of leadership will reap returns for the sustainability of inclusive civic life.

- Boost trust in local government. Local governments must continuously make themselves accessible to all residents.

- Reach across city limits. Inclusion efforts are most effective if they promote regional dialogue.

- Give it time. Communities should approach inclusion work with not only a plan and best practices but also a healthy dose of patience.

Oversimplified headlines suggest that small-town America is conflicted about the extent to which its demographic and economic vitality should depend on newcomers.4 Yet Lexington and Madison offer encouraging examples of how proactivity and practicality—coupled with time—can help communities embrace the nation’s multicultural destiny and emerge stronger for their collective efforts.

Old traditions, new demographics

On a Friday night in August 2018, John Fagot, a lifelong resident of Lexington, Nebraska, who has served as its mayor for the past 18 years, sat in the bleachers of the town’s only high school, taking in the pomp and circumstance of the annual homecoming football game. Though the mayor couldn’t see the activities on the field—an accident left Fagot blind in the early 1980s—he knew that the night’s homecoming coronation signaled that his small town had arrived at what he calls a demographic “mountain top.”5

Edvin Ortiz, son of Guatemalan immigrants, and Vanessa Lo, daughter of Cambodian immigrants, were selected by their classmates—a student body of 880 that speaks 30 languages and hails from 40 countries—to represent them as homecoming king and queen. “Only in Lexington,” Fagot mused to the people sitting next to him on the football field bleachers.6

Yet multicultural Lexington is hardly an anomaly among rural communities across the country. Small-town America—once typecast for its indisputable insularity as much as its immutable institutions—is increasingly becoming home to a growing number of immigrants and refugees. Analysis from the Center for American Progress points to a 130 percent growth among foreign-born adult populations in 2,767 rural places since 1990, offsetting a 12 percent decline in these places’ native-born adult populations.7 Many rural towns such as Lexington are retaining old traditions as they learn to embrace new demographic realities.

On that same Friday night, 175 miles across Nebraska farm country, Madison High School’s football team, the Dragons, took to the field for the season’s opening game in Madison, Nebraska. A crowd of 500 people spilled out of the bleachers and was lined up against a fence that separated fans from the field.8 It was an impressive turnout for a rural community of just 2,600 people—even more so considering that the town had not rallied around its football team for a number of years.9

Since Madison High School’s student body had flipped from majority white to majority Latino10 over the span of just a decade, a stereotype “Mexicans can’t play football”11 had emerged among longtime residents.12 Many of these new Latino students were more familiar with fútbol than football, and the Madison Dragons’ resulting record of losses and forfeits demoralized the young athletes and fueled demographic tension. But school administrators were confident that Madison’s traditions could continue even as the demography of its residents shifted.13

“We’ve got a school full of speed,” Harlow Hanson, president of the Madison Public Schools Board of Education, remarked.14 Aiming to boost team—and town—morale, Hanson championed a switch from an 11-man to an 8-man form of gridiron, where dexterity is an advantage over heft. Madison High School’s new generation of Dragons won their opening game 65-24.15

Madison and Lexington, like other towns grappling with demographic shifts, have learned that sometimes things must change so that they can stay the same. The realities of rapid demographic shifts have unsettled many communities, stoking xenophobic sentiments and polarizing dialogue about the merits of immigration and refugee resettlement.16 Yet towns that learn to accept their new normal—even if they sometimes do so begrudgingly—have enjoyed the benefits of population growth, new business development, and renewed vibrancy.17

Both Lexington and Madison offer proof that small-town life persists and perseveres, even as the faces and backgrounds of their residents change. This report tells the story of how each town weathered challenges and embraced incremental successes. These two rural small towns offer lessons for other communities grappling with demographic shifts and cultural change.

Twin trends drive change in rural Nebraska

Nebraska has a 150-year history of receiving immigrants,18 but two trends—the establishment of meatpacking plants in the rural Midwest and the decline of the native-born population across the region—have accelerated demographic changes throughout the state.

Immigrants have long powered meatpacking—an industry with a reputation for physically demanding, low-wage, and often dangerous jobs.19 A century ago, packing plants were concentrated in the nation’s urban areas. But by 2000, more than 60 percent of meatpacking jobs had relocated to America’s rural communities20—a product of packing plants’ desires to bring production closer to cattle and hog farms and to reduce labor costs,21 as workers in rural areas are less likely to be unionized than their urban peers.22

Today, companies have made significant improvements to worker protections and safety.23 Jobs are still dangerous, however, and average salaries have stagnated. The national average hourly wage—$13.46 as of May 201724—is far from its inflation-adjusted peak of nearly $20 in the 1960s through the 1980s.25 Recruitment and retention is a challenge, and many companies rely heavily on foreign-born labor: 1 in 3 of workers in the U.S. meatpacking industry is foreign born.26

The rise of meatpacking in Nebraska coincided with a sharp decline in the state’s native-born population. The farm crisis of the 1980s—when low crop prices, spiking interest rates, and plummeting farmland value led to the worst downturn in farming since the Great Depression—ravaged the Great Plains, decimating family-owned farms and shuttering businesses. Over the course of the decade, 100,000 more people left Nebraska than entered.27

The arrival of foreign-born meatpackers—first, single men from Latin American nations, followed by their families and, more recently, refugees from Asian and African countries28—reversed some of Nebraska’s economic and demographic stagnation. From 1980 and 1992, the Latino population living in 10 Midwestern states, including Nebraska, grew from 1.2 million to 1.8 million.29 And while these new residents stemmed the population drain, the so-called browning of the Midwest created new challenges.30 Literature from the 1990s describes how sudden, large influxes of newcomers strained towns’ social services infrastructure.31 Surveys conducted in the mid-1990s and early 2000s of residents in the meatpacking towns of Crete, Nebraska,32 and Schuyler, Nebraska33 point to tensions around housing shortages and decreased satisfaction with the overall quality of life in the community among long-term residents.

The new Nebraskans, however, reported an affinity for life in these small towns. Nearly 90 percent of newcomers cited being “happy” in their new communities and “likely to continue to live there.”34 For many immigrants, the agriculture-based, family-focused lifestyle reminded them of life in their home countries. Many refugees sought a simpler life after having been initially resettled in larger cities.35 Two decades later, these shared values would anchor a continued sense of community in small-town Nebraska, particularly in places such as Lexington and Madison.

Contemporary Nebraska’s attitudes about immigration are as diverse as its residents, leading to divergent approaches to immigration policy. Nebraska was among the first states in the country to pass legislation offering in-state tuition to undocumented students,36 but it was the last in the nation to offer driver’s licenses to certain undocumented youth.37 In both instances, the state’s unicameral legislature enacted the laws by overriding gubernatorial vetoes.38

Yet perspectives in Lexington and Madison suggest that a sense of shared community has eclipsed political divides on the issue. “Some of the things our president [Donald Trump] says are hard to believe,” said a white, lifelong Madison resident, adjusting his cowboy hat as he walked past a Mexican grocery store on the town’s main street. “Immigrants are our neighbors; they’re not rapists or murderers. You know the people he’s talking about. They’re not like that.”39

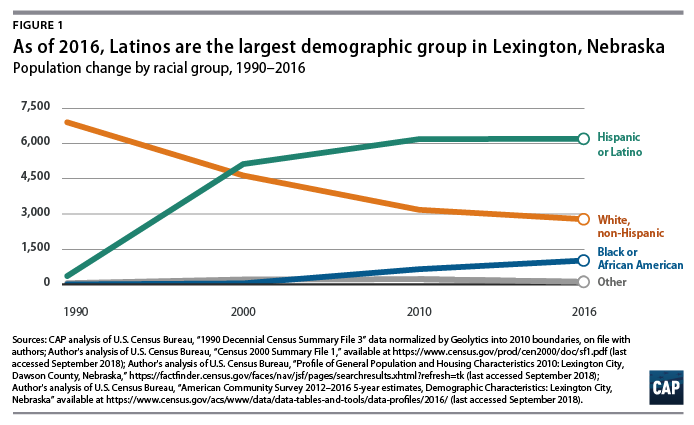

Building a multicultural Lexington

Three decades before Lexington’s high school crowned its multicultural homecoming king and queen on the football field, the town was bitterly divided about the extent to which its future should be linked to immigration. The 1986 shuttering of the town’s Sperry-New Holland combine manufacturing plant devastated the community economically and demographically, transferring many of the steady, well-paid jobs—and workers—to Grand Island, Nebraska, some 90 miles away.40 Town officials worked overtime to recruit a new business to occupy the empty facility. Those efforts meant residents had to grapple with the potential that the finalist—meatpacking giant Iowa Beef Processors Inc. (IBP)—would likely attract foreign-born workers. When IBP—which became Tyson Fresh Meats Inc. in 2001 as part of a nationwide acquisition—opened in 1990, some long-term Lexingtonians, many of them white, packed up and moved out. (see Figure 1) Others, including Lexington Mayor John Fagot, rolled up their sleeves and got to work.

“We did have some white flight when IBP moved in,” Fagot recalled. “My thoughts were, ‘If it’s your view that you don’t want to be part of our community, then please leave.’”41

Leaders from Lexington City Hall, human services agencies, and the nonprofit sector convened a community impact study team to prepare for IBP’s arrival.42 They toured other meatpacking towns, held public forums, and had planning conversations with IBP.

Leaders from Lexington City Hall, human services agencies, and the nonprofit sector convened a community impact study team to prepare for IBP’s arrival.42 They toured other meatpacking towns, held public forums, and had planning conversations with IBP.

Many of these same leaders were later involved in setting up Haven House, a temporary shelter and soup kitchen for the newly arrived workers. They also launched the Welcome Center, which offered orientation resources for newcomers and, later, immigration legal services.43

A rocky start

Despite the proactive planning, IBP had a rocky start in Lexington. Worker turnover averaged 250 percent in the early years. By 1992, IBP had hired and fired a labor force equal to three-quarters of the town’s population.44

“Our crime rates were among the highest in Nebraska when the IBP plant was being built,” Fagot recalls, attributing the statistics in part to “20- to 25-year-old males who thought they were bulletproof.”45 The jump in crime and accompanying demographic shift earned Lexington a tough reputation and disparaging nickname—“Mexington”—from neighboring communities, many of which had absorbed Lexington’s exodus of white residents. 46

Dora Vivas, who has served as city council member since 2012, arrived in Lexington in 1992.47 She was in the minority as a woman among the many men drawn to work at IBP. Born in Texas and raised in Mexico, Vivas lived at Haven House for several months after arriving in Lexington. She recalled the fraught nature of those early days of demographic change.

“People didn’t want to rent to us. When I went to the bank to cash a check, somebody told me to go home. Then they yelled a bunch of stuff I didn’t understand, except the word ‘tortillas’,” she recalled, laughing. “But things started changing little by little. It took five or six years. People started realizing that we weren’t going anywhere.”48

Working toward a new normal

After the initial wave of individual workers in the first few years, immigrant families began arriving. In short order, foreign-born entrepreneurs set up businesses—including restaurants and grocery stores—to cater to the tastes of newcomers. Local retailers caught on to the opportunities that the newcomers represented. Vivas was invited to a focus group convened on behalf of the local Walmart’s management team. “They asked me, ‘What do you need?’” Vivas said. “Before, we had to drive to Lincoln or Omaha to get Mexican products. Then they started to become available in Lexington.”49

The infusion of immigrant-owned businesses brought a new vibrancy to Lexington’s downtown, which got a $350,000 facelift in 2011, with improvements to storefronts, streets, and infrastructure.50 Bilingual newcomers staffed schools, hospitals, and banks. Children from Latino families enrolled in local schools, which initially struggled to accommodate a 50 percent enrollment bump and an influx of English language learners.51 Efforts to effectively manage change were bolstered with the support of translators from Tyson Fresh Meats and best practices gleaned from the experiences of educators and civic leaders in other meatpacking towns.52

The city purchased a vacant warehouse store—located across the street from the Tyson plant—and launched the Dawson County Opportunity Center, which became home to a preschool, the chamber of commerce, a human services agency, and a local branch of the regional community college. The college’s English as a second language (ESL) program quickly grew so popular that students had to be put on a waiting list.53

Collaboration between City Hall and Tyson helped relieve pressure on the area’s real estate market. In 2013, the city launched a plan to build 900 new housing units, with Tyson reimbursing the costs to acquire the land.54 The project, set for completion in 2030, has already seen the completion of approximately 200 units to date.55

As Lexington eased into this new normal, crime rates plummeted. State data point to a steady decline in crime reported by the Lexington Police Department since 2008; crime rates in 2017 were the lowest on record since 2000.56 According to Fagot, the town was recently ranked the fifth-safest place to live in Nebraska, outranked only by suburban communities near Omaha and Lincoln.57

Still, there are naysayers. “People outside our community just look at our demography, they’re just looking at our color. We’re not going to change their minds,” Fagot said. “But more and more, others are starting to sing our praises.”58

A new wave of newcomers

In more recent years, Lexington’s resilience has been tested by the arrival of a fresh group of newcomers: Somali refugees, many of whom had originally been resettled in Minneapolis and other regional cities. These newest arrivals were drawn to Lexington by work opportunities at Tyson and the chance to raise their children in an affordable, family-focused community.59 Census data show that in 2000, the town had just 10 foreign-born Africans; by 2016, the African immigrant community had grown to 829, accounting for 8 percent of Lexington’s population.60

Yassin Eli, a Somali refugee who moved to Lexington in 2010—after stops in Kenya, Minneapolis, and several places in between—helps his brother run Mandeeq, a restaurant which serves traditional Somali dishes in generous portions. “You work at Tyson, and on the weekends, you eat at a restaurant, you talk to people. Lexington is good. People respect you. … Most of us call Lexington a ‘cool’ city,” Eli said.61

If the initial integration of Latinos—many of whom shared Lexington’s Christian traditions and had learned English after a generation or two of living in Lexington—had given the community pause, the work of welcoming linguistically, culturally, and religiously distinct Somalis proved doubly daunting.62

Tyson hired Somali translators who worked overtime to broker conversations at City Hall and local schools, navigating the complexities of accommodating prayer time during the school day and coordinating Somali burials in Christian cemeteries.63

However, not all Lexington residents share Eli’s assessment of the changing town. Challenges came to a head in 2016, when controversy surrounding the construction of a mosque in downtown Lexington made national headlines. Somali leaders sought to convert a shuttered laundromat into an Islamic Center of Lexington, while city officials bristled at the idea of a house of worship in an area zoned for commerce and in proximity to establishments serving alcohol. The disagreement, fueled in part by the anti-Muslim rhetoric of the 2016 presidential race, spiraled further, and the case wound up in federal court.64 “It felt like my freedom of religion was being violated,” Eli said.65

Fortunately, the issue is now resolved: The mosque has opened its doors in the downtown location, and a bar and grill operates close by without issue. “It should have been more cooperative than it was. The media blew it out of proportion,” offered a city official.66 The incident still lingers as a painful low point for a community that otherwise has grown to view multiculturalism as a strength.

Nuridin Nur moved to Lexington in 2003, becoming one of its first Somali residents. He now runs African International, a successful restaurant and retail store in Lexington’s business district, where his customers reflect the town’s diversity. “Lexington is one community,” Nur said. “We help each other, we trust each other. I am friends with everybody. Mexicans say ‘Hola chaparro’—hey shorty—when they see me in the street. If you want to earn trust you have to trust first. That’s how it works in America.”67

The changing face of Madison

Like Lexington, Madison’s demographic shifts are rooted in the arrival of a meatpacking plant. IBP began operating in 1987 after having formerly leased the plant to Armour and Company.68 Armour Packing Plant had employed a unionized workforce, offering steady work and a middle-class lifestyle to Madison residents. But IBP’s arrival and the departure of Armour broke the union, drove down wages, and scattered long-term workers and their families.69 Short-staffed, IBP recruited workers from elsewhere, including Hispanic immigrants employed in the agricultural sectors of California, Texas, and Florida.70

The change was abrupt for Madison, leaving civic leaders without a proactive plan in place. The influx of new workers—mostly single men, as had been the case in Lexington—created a culture of late-night bars and activity that scandalized some in the family-focused small town.71 Madison earned the nickname of “Little Mexico,” though its population of newcomers also hailed from other Latin American and from Asian countries.72 “Madison has the reputation of being the ‘town with all the Mexicans’,” Madison Public Schools Board of Education President Harlow Hanson said. “And that’s always bothered me because it’s said in such a derogatory way. Why does it matter?”73

The change was abrupt for Madison, leaving civic leaders without a proactive plan in place. The influx of new workers—mostly single men, as had been the case in Lexington—created a culture of late-night bars and activity that scandalized some in the family-focused small town.71 Madison earned the nickname of “Little Mexico,” though its population of newcomers also hailed from other Latin American and from Asian countries.72 “Madison has the reputation of being the ‘town with all the Mexicans’,” Madison Public Schools Board of Education President Harlow Hanson said. “And that’s always bothered me because it’s said in such a derogatory way. Why does it matter?”73

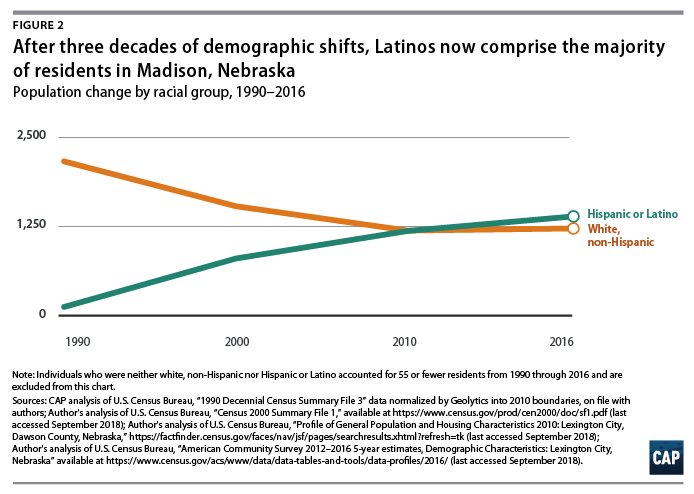

The white share of Madison’s population did not shrink to the same extent that it did in Lexington during the early years of demographic change in the town. (see Figures 1 and 2) However, its schools experienced what Madison Public Schools Superintendent Alan Ehlers called a demographic “flip-flop,” transitioning from approximately 80 percent white to 80 percent Latino. According to Ehlers, Madison’s most affluent families continued to live in town but sent their children to private or parochial schools in neighboring communities. As newcomer students worked to learn English, they struggled with standardized exams, and the district’s average standardized test scores plummeted.74

In the early 2000s, the Lexington Board of Education was frustrated in its attempts to pass a $4 million bond to expand the town’s increasingly diverse elementary school. The community voted against the bond two times,75 which illustrated the extent to which the town was divided over demographic changes.

“Longtime residents didn’t want to see the community change,” recalls Jo Lux, a retired music teacher who now leads ESL class at a local church. “People didn’t want to see their taxes go to support what became a majority Latino school. They were more comfortable seeing the school close than seeing the school change.”76

The backlash prompted Hanson to go door-to-door to engage in what were often heated conversations with unsettled residents. “The bond issue split the community like you can’t believe. Some people welcomed you with open arms, others threw you off their property,” he recalled. On the school board’s third try, voters narrowly passed the bond measure.77

An unexpected turning point

Residents point to a tragedy—an attempted bank robbery and shooting—as an unexpected turning point in Madison’s demographic transition. In 2002, four Madison Latino youth, members of a gang, walked into a bank in the neighboring town of Norfolk and opened fire. Four bank employees and a customer were killed in the incident, which prompted a series of community dialogues as both Norfolk and Madison attempted to heal.78

According to Kent Warneke, editor of the Norfolk Daily News, “Ethnic relations were still a little uneasy. There was potential for real racial tension.” But then something happened. “What helped the situation was that members of the Hispanic community grieved with the rest of the community,” recalled Warneke. “It’s wasn’t an ‘us versus them’ situation. It was obvious that we were all in this together. I think that was a turning point.”79

As Madison began the process of moving forward, it started to embrace the immigrant-owned businesses that had opened along one of the town’s main street. The town embarked on a downtown revitalization project in 2014, refreshing storefronts for businesses such as Burrito King, a town favorite.80 A line of office workers, Tyson employees, and young families regularly spills out the door of the brightly painted restaurant.

“People told me that it was a mistake to open a restaurant in such a small town. But I saw a growing community without many options for Mexican food,” said owner Francisco Valdez, a Mexican immigrant who has lived in Madison since 1999. “From the beginning, people accepted me—I have never felt racism.”81

While the town retains its rough reputation and the stigma of high crime and gang activity among neighboring communities, Madison Police Department Chief Rod Waterbury says that the data tell a different story. “We have a lower crime rate than towns our size that are all white,” he said. “You can’t get away with things here. When I do interact with people, the reality is that ‘not only do I know you, but I also know your grandma and grandpa, and I will be talking to them.’”82

Analysis of Nebraska Crime Commission data reveals that there were just 16 incidents of crime reported by the Madison Police Department in 2017, marking the lowest rate on record for the town since 2003.83

A second wave of newcomers

Madison is now applying lessons learned from the first wave of newcomers to foster the inclusion of recently arrived refugees from Myanmar. The town has not had to manage the religious differences that at times posed a challenge for Lexington; many of Madison’s newest arrivals are members of an ethnic minority known as the Karen people and are Christian.84

Evidence of the presence of Madison’s newest population comes in the form of new storefronts, including the Karen/Asian Grocery Market, which just opened at Madison’s main city entrance.85 A Karen welcoming center, funded with support from the Nebraska Karen Society and Tyson, is set to open in downtown Madison.86

As Karen newcomers work to learn English, a Tyson-employed translator accompanies them to City Hall and visits to the doctor and the local banks. According to Warneke, “With this new group of immigrants, the transition was fairly seamless. The fact that it wasn’t a big deal says a lot about the community.”87

Griselda Beery has lived the demographic transformation that has shaped Madison. She was raised on the U.S.-Mexico border—moving back and forth between McAllen, Texas, and Reynosa, Tamaulipas—and arrived in Madison in 1996. She worked at Tyson for 17 years before being recruited to the Madison Sheriff’s Office, where her bilingual skills were an asset. The mayor then appointed her to fill a vacancy on the City Council last year, making Beery Madison’s first Hispanic—and only female—council member.

“It’s a calm little town. Integration is easier now,” said Beery. She thinks that Madison’s experience with demographic change over the past three decades has “opened up a path for new immigrants. People are used to it now.”88

Contemporary successes and challenges

With this newest wave of immigrants, the residents of Lexington and Madison—old and new—are back to the business of getting to know each other, and many of the lessons learned in integrating Latino newcomers a generation ago are facilitating inclusion this time around. Locals view this as a work in progress. As one lifelong Madison resident noted, “The melting still isn’t happening in some areas.”89 Still, there has been a great deal of success thanks to the efforts of local schools and the Tyson Fresh Meats plants as key drivers of inclusion in both communities, along with a largely decentralized network of dedicated civic leaders and organizations.

Schools drive community inclusion efforts

While initially a challenge, diversity is now a tangible source of pride in schools in both Lexington and Madison. Visitors to the schools are greeted by displays of flags that represent students’ diverse countries of origin, and multiple languages can be heard echoing through the halls.

Meeting the linguistic needs of newcomer students was a hurdle that the Madison and Lexington school districts have worked hard to overcome. In Lexington, an English as a second language program that launched with just one part-time teacher more than two decades ago has blossomed into a dual-language (Spanish and English) curriculum—one of only two programs in the state, the second being a program in Omaha.90 Madison has welcomed several immigrant graduates back to its schools as teachers, including a former ESL student who now coordinates the elementary school’s English language learner (ELL) program. In fact, the Madison school district has built ELL programs that seamlessly serves students in all grade levels. “Our ELL program is 5,000 times better [than when we started],” said Jim Crilly, the Madison high school principal. “Not because we didn’t want it then, but because we just didn’t know any better.”91

Schools now understand that serving the needs of newcomer students—many of whom live below the federal poverty line and may have had lapses in their education—goes beyond simply teaching them English.92 Lexington High School Principal Kyle Hoehner cited his school’s “Destination Graduation” effort—a 7-year-old relationship-based program designed around students’ diverse academic, social, and emotional needs—as a “game changer” for the multicultural school.93

Both school districts make parent engagement a priority. Demanding work schedules at Tyson, coupled with a host of linguistic and cultural factors,94 initially kept immigrant parents away from parent-teacher conferences, committees, and extracurricular activities. In the early 2000s, Jerry Bergstrom, the now-retired principal at Lexington’s Pershing Elementary School, worked with the University of Nebraska at Kearney convene a series of “learning circles” with parents, teachers, and students around the immigrant experience. The Developing Networks program initially trained 28 facilitators, who in turn engaged 180 people in communitywide conversations.95 Dialogue expanded to the high school, where students led conversations with their peers. “The biggest learning was that we all want the same thing,” Bergstrom explained.96 In 2007, the program won a national social justice award.97

In Madison, community support of the schools has improved significantly. More than 50 community members serve as mentors of Madison students via a program founded on the idea that “learning happens both ways.”98 After rejecting previous school bonds, the town in 2018 backed a $6 million proposal for middle and high school renovations, to be financed via a special building fund. “We got everybody in one room—Latinos and longtime landowners, business leaders—we invited everybody and talked to everybody,” Madison Public Schools Board of Education President Harlow Hanson said.99

Districts where the socio-economic realities are stacked against students’ success produce exceptional academic outcomes. While both communities have some of the highest poverty rates in Nebraska—more than 3 in 4 students qualify for free or reduced-price lunch—Madison’s and Lexington’s only high schools consistently boast graduation rates above the state average of 90 percent.100 “We are driven to accomplish that which others perceive to be impossible,” explained Hoehner. He cited the Lexington High School motto: “If one wants to see the world, just cross the threshold of our front door.”101

Tyson’s support extends beyond its plants’ walls

The meatpacking plants, once criticized by many locals for setting in motion the demographic challenges that ailed Madison and Lexington, have since emerged as important players in fostering inclusion in both communities. Programs designed by Tyson to support its diverse employees reap benefits beyond the plants.

Tyson translators are deployed across both towns to assist newcomer plant staff in everything from setting up utilities to going to the doctor and enrolling their children in schools. Translators are also available on-call to community organizations, local businesses, and City Hall. “They’re going to rely on us to provide [interpretation] until they can get it shored up for themselves,” said Suzann Reynolds, a senior human resources manager with Tyson.102

The meatpacking plants employ a network of community liaisons that sit on nonprofit boards and staff diversity fairs, developing collaborative relationships with institutions across the town.103 Tyson has also recruited a network of chaplains, who provide counseling services to staff along with referrals to community organizations. Heidi Revelo, chaplain at the Tyson plant in Lexington, described herself as an advocate. “I educate Somalis on U.S. culture, I educate Americans on Somali culture,” she said. In addition, Revelo said she does “a lot of troubleshooting.”104 For example, when a community effort to donate back-to-school supplies didn’t draw any Somali families, Revelo pointed out that the location—a Christian church—may have kept them away.105

Tyson has also worked with civic leaders to relieve the pressure on the housing market in both communities. Recently, ground was broken for a new housing subdivision on the south end of Madison, close to the plant. Local banks, a community foundation, and Tyson have collaborated to subsidize the lots that are being offered at $20,000 each to all new homebuyers.106

Community networks bolster institutional efforts

In both towns, a network of nonprofit and civic organizations bolster work being done in the schools and at the plants.

Lexington’s culture of proactive collaboration, born out of preparations for the Iowa Beef Processor plant’s 1990 opening, has continued to the present in the form of regularly scheduled stakeholder meetings. Local human services agencies and nonprofits, along with City Hall representatives and Tyson liaisons, convene bimonthly to discuss community needs and how best to meet them, with an emphasis on building shared responsibility for success without duplicating efforts. Immigration, a frequent focus of these meetings, is couched within a framework of building a community that works for everyone.107

For the past two years, Lexington has hosted a communitywide “United by Culture” festival, showcasing the city’s diversity with food, music, and performances. The inaugural event boasted an attendance of 1,000 people. One of the festival organizers, Gladys Godinez, was quoted in the Lexington Clipper-Herald: “We organize this event to help people come out of their living rooms to interact with people of a different culture … This is important because right now, our differences are being highlighted in the wider world more than what brings us together.”108

In Madison, the public library has worked hard to attract newly arriving immigrants, coordinating a public relations campaign to tackle a misconception among Latino newcomers that the Madison Public Library is a for-profit librería, or bookstore.109 “We had to work through the schools to convince them that our services were free,” said Naomi Hemphill, an assistant librarian at Madison Public Library.

Building the next generation of civic leaders

For all their successes, both communities have been frustrated by stalled efforts to engage newcomers in civic leadership roles. The challenge is a product of newcomers’ assumptions about local government based on their own often-strained relationships with government in their home countries, demanding work schedules, and a growing distrust in U.S. government—the latter stemming, at least in part, from the divisive federal climate on immigration.110 In both communities, immigrants and refugees have been reluctant to get involved in school boards, city committees, and the chambers of commerce.

Lexington Mayor John Fagot recognizes the complexity of this challenge but thinks it stems from generational—rather than cultural—differences. “I’ve spoken to mayors in other communities about this, and we’re not alone,” he said. “Our [diverse] demographics don’t have as much to do with it as trying to get the younger generation involved.”111

Lexington is part of a countywide effort to bridge the generational divide with the launch of a youth leadership program—a partnership between the county economic development board, community college, and high schools. Lexington will send 12 high school juniors to participate.112 Madison has explored a similar program, which would engage high school civics students in activities at City Hall.113

The hope is that the programs will add to a new, diverse leadership pipeline—the beginning of which is being built by Latina city council members in both communities. Griselda Beery is serving in Madison, while Dora Vivas—the trailblazing immigrant who once lived at Haven House, the temporary shelter and soup kitchen—was elected in Lexington in 2012.114

Vivas encourages other newcomers to get out of their comfort zones and get involved in civic life. “I tell them, ‘You can’t be discovered by hiding,’” she said. “Increased representation is going to be up to us.”115

A road map for inclusion

Lexington and Madison have much to celebrate across three decades of managing demographic change: the successful integration of newcomer students in local schools; the establishment of flourishing immigrant-owned businesses; and a sustained sense of community and tradition amid the adaptations.

These two towns’ distinct journeys are testament to the fact that there is hardly a one-size-fits-all approach to integration, particularly in smaller, rural communities with strong local cultures and small groups of civic actors. Yet Lexington’s and Madison’s ongoing efforts have benefited from many of the same practices, as they have grappled with similar challenges. Shared experiences offer a road map to other communities in adapting to change:

- Embrace innate advantages. When welcoming newcomers, small towns should embrace the innate advantages—intimacy, efficiency, and familiarity—that their big-city counterparts lack. Staff at Nebraska Appleseed, a nonprofit that supports inclusion work throughout the state, has observed that towns of fewer than 20,000 people lack the ethnic enclaves of larger cities.116 Such intense integration can be jarring initially, with no buffer for linguistic or cultural differences. But newcomers in both Lexington and Madison agree that it helped them learn English faster, and long-term residents report that it facilitated getting to know the newcomer families on their block. “Neighbors live side-by-side here,” remarked Lexington Mayor John Fagot. “And as we’ve moved through that, people have realized that any differences weren’t that big.”117

- Emphasize shared values. Communities that emphasize common core values—work, family, and faith—can effectively bridge other language or cultural differences. No matter their background or country of origin, the residents of Madison and Lexington share an affinity for small-town living and core values of family, hard work, and faith. Newcomers in both communities consistently expressed appreciation for the quiet, family-focused nature of their communities—aspects that contrasted sharply with the larger U.S. cities where many immigrant families—particularly resettled refugees—had previously lived.118 Long-time residents cite an admiration for newcomers’ family values and work ethic.119 And although residents hail from different religious traditions, they share a strong faith in a higher power that guides their moral compass. In both communities, shared values have facilitated a melding of cultures, especially as residents’ children have experienced school, extracurricular activities, and various rites of passage together. “We’ve picked up a lot of the Latino community’s [traditions], like quinceañeras,” said Madison Police Department Chief Rod Waterbury. “White people don’t have them, but we definitely go to them.”120

- Partner with the private sector. When the rate of demographic change outpaces a community’s ability to keep up, public-private partnerships can be a lifeline. The meatpacking industry’s challenging history of low wages, dangerous work conditions, and antipathy toward labor unions has been documented in literature on immigration in rural communities.121 Yet the reality is that companies such as Tyson—by far the largest employer in both Lexington and Madison—are now making investments to mitigate the challenges that the industry initially put in motion, particularly around the integration of its foreign-born workers. Tyson translators, liaisons, and chaplains are filling resource gaps at schools and city halls. Funds from Tyson have subsidized housing developments in both communities. Tyson has purchased school equipment in Madison, sponsored sports teams in Lexington, and donated thousands of dollars’ worth of in-kind products to community fundraisers.122

- Govern consistently. Inclusion efforts work best when local policies are designed to benefit all community members, not just newcomers specifically. Fagot says, “We’re not changing anything in Lexington unless we change it for everybody.”123 The application of this idea has created tension, especially when newcomers’ customs clash with city laws, but it has also helped residents appreciate their similarities. The Madison Police Department has received complaints about loud noise from worshippers at the new evangelical Latino churches in town, but City Hall counters that the bells at long-established churches would also have to be silenced if noise ordinances were applied to houses of worship.124 Lexington City Hall shut down a request for a policy limiting the butchering of hogs on private property when it pointed out that the same rules would to apply to deer hunters.125

- Build leadership pipelines. Investments in the next generation of leadership will reap returns for the sustainability of inclusive civic life. In both Lexington and Madison, a small cohort of dedicated civic leaders guides the bulk of inclusion work. As these leaders have left their posts, their work has ended. For instance, after a decades-long run, Lexington’s Welcome Center shuttered when its sole staffer left the organization.126 In Madison, a 70-year-old English as a second language teacher expressed concerns about what will happen to the program, held in a local church basement, when she’s gone.127 Each town’s positive momentum must now be sustained as this established, mostly white, group of civic leaders seeks to pass the baton to the town’s next generation—a multicultural cohort with comparatively shallow roots in each community. In both towns, leadership development programs being coordinated via local schools show promise in building pipelines.

- Boost trust in local government. Communities will prosper only with the engagement of their full population. Local governments must keep making themselves accessible to all residents. Day-to-day life in rural Nebraska often plays out with only a peripheral awareness of the deeply polarizing realities of current federal politics, especially around immigration.128 However, when the federal intersects with the local, people of all backgrounds take notice. The shock of an August 2018 immigration raid in O’Neill, Nebraska, with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents arresting and detaining more than 100 undocumented workers, reverberated throughout the state.129 Tight hiring practices at Tyson and the work permits given to resettled refugees mean that many of Lexington’s and Madison’s foreign-born residents hold work authorization. Some have lived in the United States long enough to naturalize and are now U.S. citizens. Yet even though the possibility of deportation may not be a daily concern, fear manifests in more subtle ways: intimidation when interacting with local government or hesitancy to fill out a census form. Communities must continue to build trust among all residents.

- Reach across city limits. Today’s efforts to foster inclusion will be most effective if those efforts extend across city limits and promote regional dialogue. The white flight that characterized the early days of demographic change in Lexington and Madison has had the longer-term effect of isolating these multicultural towns among less diverse—and less-tolerant—neighboring communities. Newcomers, including youth, cite examples of painful interactions—ranging from verbal assaults to physical assaults—when they leave Lexington and Madison city limits.130 Nebraska authorities reported 46 hate crimes statewide in 2017, up from 26 in 2016. Thirty-five of those crimes were based on race or ethnicity.131 Rural Nebraskans’ self-selection along polarizing political and ideological lines mirrors the dangerous trends that have divided the country. Efforts to promote regional dialogues on immigration and integration from organizations such as Nebraska Appleseed, Welcoming America, One Siouxland, and the Center for Rural Affairs are ripe for replication.

- Give it time. Communities grappling with demographic change should approach inclusion work armed with not only a plan and best practices but also a healthy dose of patience. Proactive, intentional efforts in both towns have been bolstered by wider, organic efforts that have evolved over time—and now, lessons learned three decades ago are being applied to address contemporary challenges. The new normal in Lexington and Madison illustrates that integration is possible but takes time to achieve. The most dramatic demographic differences dissipate after a generation or two. This eventuality of integration has proven true throughout the United States’ history. “It’s going to take time,” Fagot said. “We’re breaking ground for everybody.”132

Conclusion: Looking ahead

Three decades ago, the emerging normalcy of multicultural life in Lexington and Madison likely would have seemed impossible to residents at the beginning of their long climbs to a demographic “mountain top,” as Lexington Mayor John Fagot put it. But today, both towns have successfully scaled significant challenges and have much to celebrate.

Madison and Lexington boast successful schools, revitalized downtowns, booming housing markets, and sustainable population growth, all infused with a largely consistent, if unexpected, affinity for life in a multicultural community. These towns and their residents welcomed new flavors in local restaurants, opportunities to raise bilingual children, and exposure to different religions and traditions. Through the demographic changes, the core values that have powered these communities for generations—family, hard work, faith, and even football—continue to run strong.

Residents of Lexington and Madison are quick to concede that their towns are not perfect and that there is no silver bullet when it comes to integration work. But common ingredients do exist, and in politically challenging times, the success in these small towns offers a road map—and a measure of hope—for the rest of the country. These two rural Nebraska towns are proof that America’s difficult history in integrating newcomers will inevitably repeat, but so will eventual inclusion. Communities that roll up their sleeves to proactively and patiently manage demographic change will emerge stronger for their efforts.

Malena Ward, editor of the Lexington Clipper-Herald, offers sage perspective on her community’s success in managing such a dramatic demographic transformation: “It’s remarkable that this all is happening in a small town,” she said. “Or maybe it’s remarkable because it’s happening in a small town.”133

About the author

Sara McElmurry is a nonresident fellow at the Chicago Council on Global Affairs, where she has contributed to a portfolio of research on immigration to the Midwest since 2014. She is also an award-winning communications strategist and consultant, having built media advocacy and multicultural outreach platforms for national and local nonprofits focused on immigration policy.

Acknowledgments

The author is indebted to the residents of Lexington and Madison—the list of specific individuals is too long to include here—whose irrefutable ability to welcome a stranger was on full display when she visited their communities. The author also thanks the experts from regional and national organizations—including the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, the University of Kansas, the Center for Rural Affairs, Welcoming America, Nebraska Appleseed, One Siouxland, Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Service, and the Immigrant Legal Center—who provided invaluable counsel and connections. Thanks go to Tyson Fresh Meats for facilitating access to its Lexington plant. Gratitude is also due to colleagues at the Center for American Progress and the Chicago Council on Global Affairs for their support of this project, data analysis, and editorial inputs.