On August 18, 2016, the deputy attorney general of the U.S. Department of Justice, or DOJ, directed the Bureau of Prisons, or BOP, to begin phasing out its use of private prisons. The decision came after the department’s Office of Inspector General issued a report that identified more per-capita safety and security incidents in private prisons than in comparable BOP institutions.

The DOJ’s ability to work toward ending its use of private prisons was made possible, in large part, through the adoption of various smart and widely supported criminal justice reforms in recent years. These reforms have helped reduce the federal prison population and thereby ease the pressure on the BOP to turn to private prison companies. Together, the DOJ’s efforts to reduce its prison population and cut ties with private prisons are commendable steps in the right direction that the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, or DHS, should follow.

The largest federal client of private prison companies is the Department of Homeland Security

Even when the number of people incarcerated in federal prisons peaked at nearly 220,000 inmates in 2013, the BOP’s reliance on private prison companies was fairly minimal. In fact, it is the DHS—the U.S. government’s largest federal operator of detention and supervised release programs—that relies most heavily on private prison contracts. The DHS is funded to maintain 34,040 beds daily to hold immigrants involved in removal proceedings or awaiting removal. Unlike those in BOP custody, these people are part of civil, not criminal, proceedings.

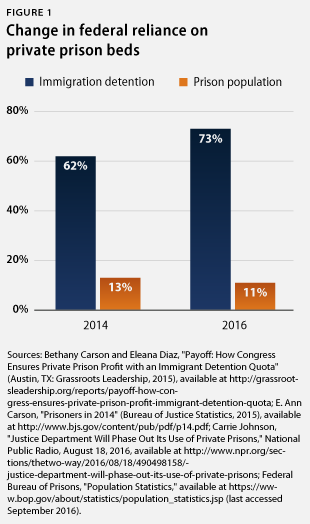

In 2014, 62 percent of immigrants in detention were housed in facilities run by private prison companies; this year, that share has risen to 73 percent. (see Figure 1) Comparatively, slightly less than 13 percent of all BOP prisoners were held in private prisons in 2014. That share dropped to 11 percent in 2016. The BOP projects it will have less than 14,200 prisoners in private prison beds by May 2017, a little more than 7 percent of its total beds.

In the immediate aftermath of the DOJ announcement, shares for the Corrections Corporation of America, or CCA, and The GEO Group Inc., the largest operators of private prisons in the United States, fell precipitously. But the significance of these companies’ immigration detention contracts is particularly apparent in their most recent Securities and Exchange Commission, or SEC, filings.

According to CCA’s February 2016 SEC filing, while federal government contracts as a whole accounted for 51 percent of the company’s 2015 revenue of $1.79 billion, contracts from DHS’ Immigration and Customs Enforcement, or ICE—which the DOJ announcement does not affect—accounted for nearly half that amount: 24 percent, up from 13 percent in fiscal year 2014. BOP contracts accounted for 11 percent of revenue, and the U.S. Marshals Service, or USMS—which the announcement also does not affect—accounted for 16 percent. Just one of ICE’s family detention facilities—the South Texas Family Residential Center, which holds women and children, mostly asylum seekers from Central America—accounted for $244.7 million of CCA’s 2015 revenue.

In The Geo Group’s February 2016 SEC filing, the company noted that federal government contracts accounted for 44.9 percent of its 2015 revenue of $1.8 billion. BOP contracts accounted for 15.6 percent, USMS contracts accounted for 11.6 percent, and once more, ICE contracts accounted for the highest share at 17.7 percent. As detailed in an earlier Center for American Progress issue brief, the growth of ICE’s detained population over the past decade largely tracks the growth in congressional lobbying expenditures by CCA and The Geo Group. These lobbying expenditures are specific to homeland security appropriations.

The DHS should follow the BOP’s lead and end its reliance on private prisons

Shortly after the BOP announced its intention to stop using private prisons, DHS Secretary Jeh Johnson directed the Homeland Security Advisory Council to evaluate whether ICE should do the same and to submit a report by November 30, 2016. As the advisory council conducts its review, it should consider the substantial evidence that the problems found at privately run BOP facilities often plague privately run ICE facilities as well. ICE contracts with the same private prison companies as the BOP, and reports indicate that ICE has long provided inadequate oversight and accountability. Privately run immigration detention facilities have been linked to a failure to identify serious health needs; the provision of substandard medical care resulting in death; a failure to prevent suicide attempts and suicides; a failure to report and respond to sexual assault; and a failure to provide adequate access to legal services.

Similar to the BOP, the DHS can reduce and ultimately eliminate its reliance on private prisons by adopting sensible reforms to reverse the growth in detention. In the past 20 years, the immigration detention system has ballooned, increasing in size from 7,500 federally funded beds in 1995 to 34,040 federally funded beds today. But the size and nature of the unauthorized immigrant population currently in the United States is also changing. In each year since 2008, the unauthorized population has declined and apprehensions by border officials—a common metric used to measure the number of unauthorized crossings—remain at low levels not seen since the early 1970s. Despite these facts—and DHS’ focus on the priority enforcement categories outlined in Secretary Johnson’s November 2014 memo—the number of detention beds has remained around 34,000, at a cost to the federal government of more than $2 billion annually.

The circumstances under which immigrants end up in detention has also been changing. An increasing number of immigrants in detention are individuals and families seeking protection from extreme violence in their home countries. Credible-fear cases rose from 8,926 in FY 2010 to 62,403 by June of FY 2016. In early 2015, 87.9 percent of women and children in detention were found to have a credible fear of persecution. The detention of these vulnerable populations—particularly in facilities owned and operated by for-profit private prison companies—should largely be phased out.

Congress also should eliminate the bed quota that requires the DHS to maintain a set number of total beds available for use, instead of allowing the department to maintain bed space based on its actual needs. Furthermore, immigration detention contracts should not include guaranteed payments for a set number of beds, regardless of whether or not they are used. These policies do nothing to improve enforcement of immigration laws; they only provide private prison companies with a reliable customer and eliminate the concerns about uncertain funding appropriations and fluctuations in occupancy rates that CCA raised in a 2005 SEC filing.

The DHS can reduce its detention population by taking steps that include ending the unnecessary detention of vulnerable populations such as families, LGBT people, and asylum seekers; providing bond hearings before an immigration judge for people detained for prolonged periods of time; and expanding the use of alternatives to detention. This, in turn, would help the department eliminate its use of private prisons.

Sharita Gruberg is a Senior Policy Analyst for the LGBT Research and Communications Project at the Center for American Progress. Tom Jawetz is the Vice President of Immigration Policy at the Center.