See also: “Hooked on Accreditation: A Historical Perspective” by Antoinette Flores1

The origins of accreditation

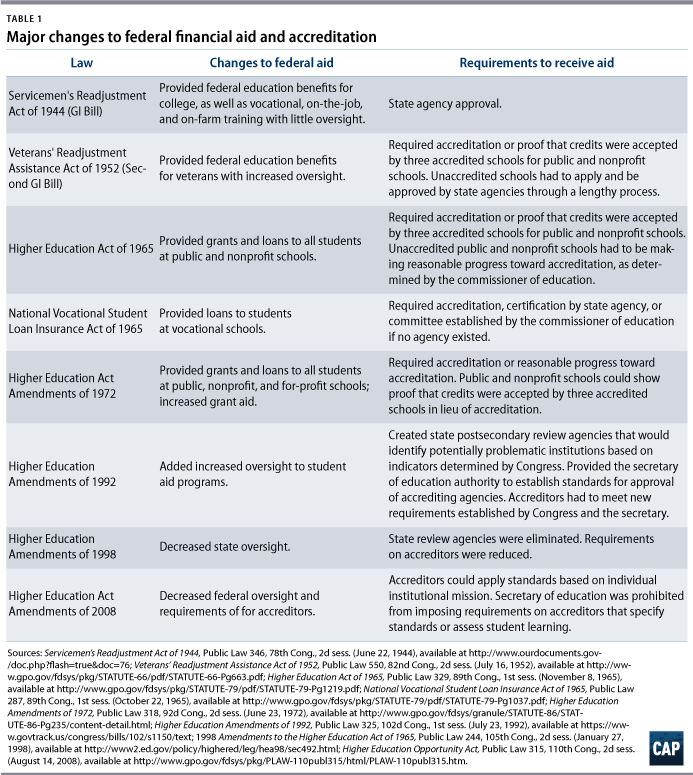

Accrediting agencies are independent membership associations. Today, they serve as gatekeepers to more than $120 billion in federal student aid dollars each year—but it wasn’t always that way. The college accreditation process long predates the advent of federal student aid programs. Colleges created the first accreditation agencies in the late 1800s to set standards around curricula and degrees. And for decades, accreditation had no interaction with the federal government.

The 1944 GI Bill

From 1944 to 1951, the federal government spent $14.5 billion on the education and training of 8 million GIs returning from World War II. While the GI Bill was groundbreaking legislation, it also gave rise to a seedy subindustry of fly-by-night operations. Over the five years following the bill’s passage, almost 6,000 for-profit schools sprung up and took advantage of the new federal education funds. A round of federal investigations uncovered massive fraud.

The 1952 GI Bill

Faced with the need to weed out bad college actors and protect students, Congress turned to the accreditation system for help. The Veterans’ Readjustment Assistance Act of 1952 required that institutions receiving GI Bill funds be accredited. Since the passage of this second GI Bill, the federal government’s relationship with accreditors has been intended to protect students and taxpayers’ investments by keeping out fraudulent actors.

The Higher Education Act of 1965 and National Vocational Student Loan Insurance Act of 1965

Buoyed by the success of the 1944 and 1952 GI bills that provided opportunity for millions of veterans, the federal government expanded federal aid for college in the 1960s and 1970s to cover students beyond veterans. In 1965, Congress passed the Higher Education Act (HEA), which opened federal grants and loans to all students who wanted to pursue postsecondary education. The bill limited access to federal grants and loans to accredited public and nonprofit institutions. Similarly, the 1965 National Vocational Student Loan Insurance Act allowed for-profit business and trade schools to access federally insured loans—but not grants—if they had accreditation.

Higher Education Act Amendments of 1972

The 1972 HEA reauthorization further broadened the type of education providers that were eligible to receive federal financial aid by allowing accredited business and trade schools to receive federal student grants. The amendments also expanded the volume of aid available by creating the Basic Educational Opportunity Grant, now known as the Pell Grant. Because so many for-profit trade schools wanted access to these funding sources, new accreditors emerged to serve as their gatekeepers. Many of these entities had no history of serving a quality improvement function.

Higher Education Amendments of 1992

Beset by concerns about rampant waste, fraud, and abuse among schools, and following years of high default at for-profit colleges in the 1980s, Congress passed the Higher Education Amendments of 1992. For the first time, lawmakers delineated what they expected of accrediting agencies, while also assigning states and the federal government more formal roles in the accreditation process. The 1992 HEA reauthorization defined specific indicators, such as curricula, successful student achievement, and fiscal capacity, on which accreditors had to have standards when approving schools. For states, policymakers proposed the creation of new State Postsecondary Review Entities (SPREs), which required states to work with the U.S. Department of Education to develop standards and identify problematic institutions. The U.S. secretary of education also received new authority to establish standards for approving accrediting agencies as gatekeepers.

Higher Education Amendments of 1998

Following widespread backlash from some states objecting to the Department of Education’s increased authority, institutions that wanted to maintain independence and autonomy, and a new Congress that promised government deregulation, the 1998 HEA Amendments reversed many of the strict federal standards imposed on states, accreditors, and institutions. SPREs, which required increased state oversight, were outright eliminated. Congress also eliminated some of the requirements imposed on accreditors, such as needing to check tuition and fees, conduct investigations into default rates, and have mandatory unannounced visits to colleges. Dialed-down language reflected the view that the federal government should stay out of enforcing standards altogether.

Higher Education Act Amendments of 2008

The 2008 HEA Amendments continued the trend of reducing the role of the federal government, giving accreditors greater freedom to act without strong oversight and affording institutions more leeway. First, the amendments required that accreditors apply quality standards with respect to individual institutions’ missions, which could vary based on standards established by the institution. In effect, this made accreditors serve the role of gatekeeper while letting schools define what it takes to unlock the door. Second, the act prohibited the secretary of education from establishing standards by which accreditors must abide in assessing student achievement. All of the changes combined made accountability increasingly difficult to demand and even harder to define.

The legislative history of accreditation shows that fraud and abuse of the federal aid system have persisted despite repeated attempts to enact oversight and steer accreditors toward consumer and taxpayer protection.

Antoinette Flores is an associate director for Postsecondary Education at the Center for American Progress.