In recent years, U.S. apprenticeship programs have become popular among politicians, workforce advocates, workers, and employers—and it’s easy to understand why. According to the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL), people who complete an apprenticeship program can expect to earn an average annual income of approximately $60,000—slightly above the 2016 U.S. national median household income.1

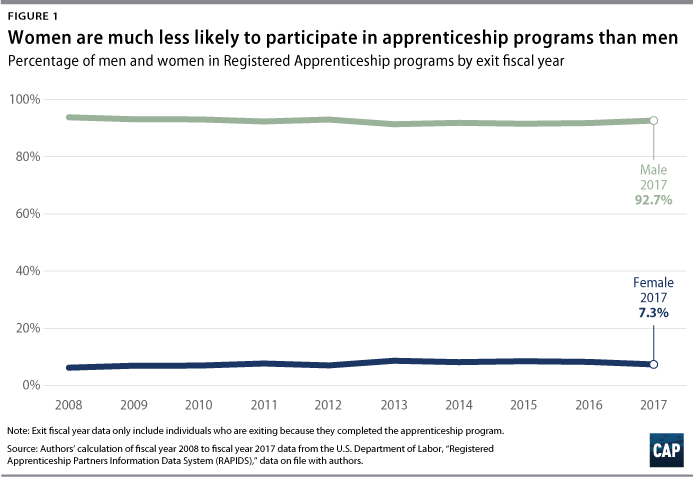

Yet, too little is known about racial and gender representation in these programs. Apprenticeship—which combines on-the-job training with classroom instruction—tends to be dominated by the building and construction trades. This suggests that these programs, like the construction workforce more broadly, are disproportionately male.2 Indeed, men make up the overwhelming majority of those who participate in apprenticeship programs in the United States. According to the DOL’s own analysis, women made up less than 7 percent of all apprentices in 2013—even though they made up 47 percent of the labor force during the same year.3

The analysis in this issue brief examines apprenticeship programs over the past decade—from fiscal year 2008 through 2017—to observe gaps in participation and wages among women and people of color. In general, it finds that women remain deeply underrepresented in apprenticeship programs and that wages among women and black or African American apprentices are much lower than those of other apprentices. Even though these programs are intended and have the potential to develop the U.S. workforce, increase earnings, and prepare workers for the jobs of the future, their current gender and racial compositions tell a different story;4 more work must be done to make it a reality.

Efforts to ensure equity in Registered Apprenticeships

Registered Apprenticeships are apprenticeship programs that are registered with the DOL and are governed by regulations laid out under the National Apprenticeship Act.5 These regulations lay out labor standards for the programs and govern their Equal Employment Opportunity (EEO) rules. In general, the EEO rules prohibit apprenticeship sponsors—typically employers or unions—from engaging in discrimination, as well as require them to take affirmative steps to ensure EEO, including efforts to recruit from a broad pool of potential apprentices. Furthermore, sponsors with five or more apprentices are required to develop a written affirmative action plan and conduct an apprenticeship utilization analysis to ensure that they are drawing adequately from the local pool of available workers.

In 2016, the DOL rewrote the EEO regulations—which had not been updated since 1978—to align them with existing labor standards; extend protections preventing discrimination based on age, disability status, sexual orientation, and genetic information; and strengthen affirmative action provisions. Implementation of the final rule is underway.6

At the same time, the previous administration and Congress took steps to help ensure that more underrepresented populations have access to apprenticeship programs. Between 2015 and 2017, the Obama administration and Congress invested more than $265 million in expanding apprenticeship programs. The DOL has used this funding to support a range of expansion initiatives, including efforts to diversify apprenticeship programs.7

Some of the available funding—$20.4 million—has been used to support industry and equity intermediaries. Equity intermediaries are tasked with providing technical assistance, disseminating best practices, and developing local and regional partnerships that will help expand apprenticeship access to underrepresented groups, such as women, people of color, and individuals with disabilities. In 2016, the DOL awarded equity intermediary contracts to four regional and national intermediaries.8

In 2018, the current Congress appropriated an additional $145 million to support these programs. And the Trump administration’s fiscal years 2018 and 2019 budget proposals called for $90 million and $200 million in apprenticeship investments, respectively.9 Yet, the Trump administration has also introduced plans to set up a parallel apprenticeship system that could undermine the current Registered Apprenticeship system. The proposal is still in development but was previewed in a report by President Donald Trump’s Task Force on Apprenticeship Expansion earlier this year.10 It would establish new so-called industry-recognized apprenticeship programs (IRAPs) that would be approved by third parties, rather than by the DOL. While details are still forthcoming, the task force report did recommend that Davis-Bacon Act wage requirements, as well as requirements that apprentices’ wages increase over time, should not apply to IRAPs.11 A parallel system with weaker labor standards and enforcement mechanisms could have negative impacts on underrepresented groups who already earn lower wages.12

Apprenticeship outcomes for women and people of color

This brief’s analysis of apprenticeship program wages and participation relied on data from the DOL Office of Apprenticeship’s Registered Apprenticeship Partners Information Management Data System

(RAPIDS) database.13 It looks at workers’ participation in apprenticeship programs over the past decade, paying close attention to wages and outcomes among different demographic groups. The analysis is limited to individuals who completed Registered Apprenticeship programs.

The following sections discuss the findings in more detail.

Women are largely underrepresented in apprenticeship programs

In 2017, 92.7 percent of those completing Registered Apprenticeships were men and 7.3 percent were women. Although women’s participation has increased since 2008—when they made up just 6.2 percent of those who completed Registered Apprenticeships—the difference is lackluster at best. This puts into question how accessible apprenticeship programs are for women, who, like men, also need high-paying, relevant jobs and career paths.14

Women who participate in apprenticeship programs make far less than men

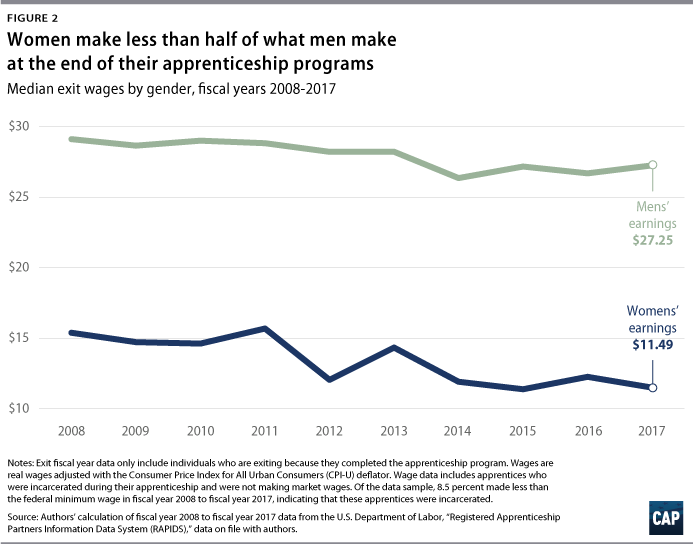

The data illustrate the existence of a substantial gender wage gap among apprentices, one that is far more severe than the overall gender wage gap in the United States.15 In 2017, among people who completed a Registered Apprenticeship, a woman made only 42 cents to a man’s dollar. Surprisingly this trend has worsened since 2008, when women made 53 cents to a man’s dollar. (see Figure 2) Some of this gap may be explained by the fact that female apprentices are more likely to complete their program while incarcerated than are male apprentices. More than 18 percent of female apprentices who have completed their Registered Apprenticeship are incarcerated, compared with just 7.7 percent of male apprentices. Apprentices who are incarcerated earn much less than the federal minimum wage: From 2008 through 2016, the median exit wage—after completing the apprenticeship—for an incarcerated apprentice was just 35 cents per hour.16

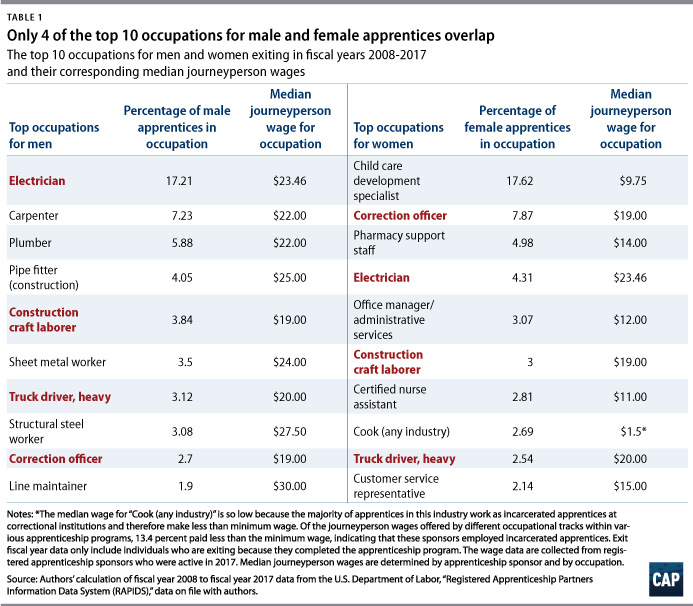

This brief’s analysis also examined differences in occupations for apprenticeship completion by gender. As shown in Table 1, occupational segregation by gender is a reality in apprenticeship programs, as only four of the top 10 occupations for men and for women are the same. Additionally, the top occupations for men tend to have higher-paying journeyperson wages—wages earned by a person trained and properly recognized in a trade—than do the top-paying occupations for women. For an electrician, the top occupation for male apprentices, the median journeyperson wage is $23.46 per hour. For a child care development specialist, the top occupation for female apprentices, the median journeyperson wage is only $9.75.

Black and Hispanic participation in apprenticeships roughly mirrors these groups’ participation in the labor force

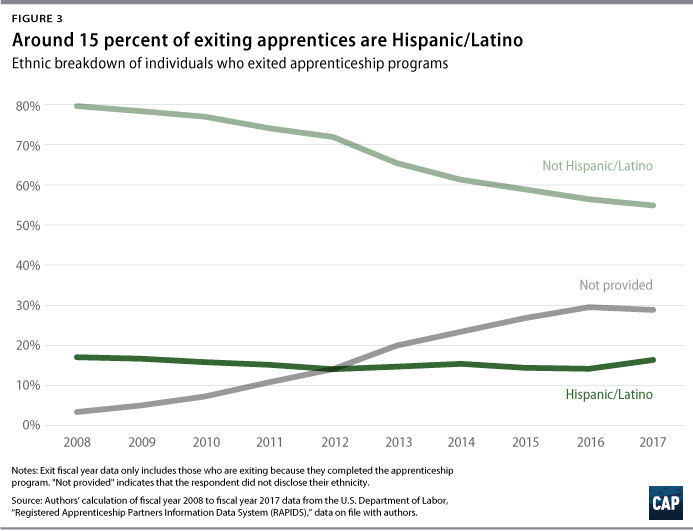

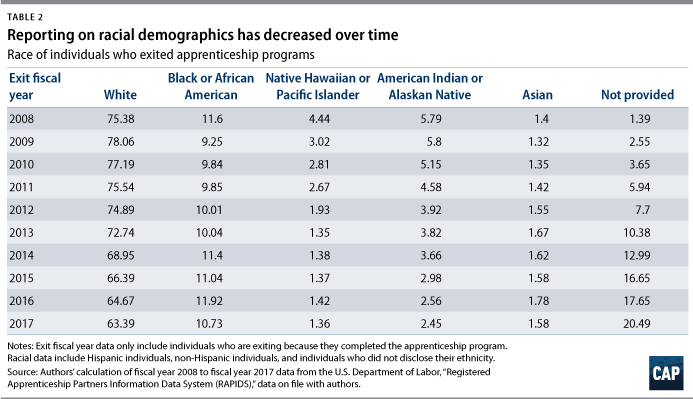

In fiscal year 2017, a little more than 16 percent of those who exited apprenticeship programs identified as Hispanic or Latino, a rate slightly lower than the share of Hispanic/Latinos in the U.S. labor force.17 In 2017, 63.4 percent of individuals who completed Registered Apprenticeship programs were white, 10.7 percent were black or African American and 20.5 percent did not provide their race to their Registered Apprenticeship sponsor. Nationally, however, the U.S. population is both whiter, at 77 percent, and more black or African American, at 13.4 percent.18

One challenge in identifying trends in participation by ethnicity and race is that the share of those who do not provide their ethnicity or race has increased significantly over time, with 29 percent of apprentices not providing their Hispanic/non-Hispanic ethnicity in 2017—up from 3.3 percent in 2008—and 20 percent of apprentices not providing their race in 2017—up from 1.4 percent in 2008.19 This likely indicates a wider issue with survey administration and a lack of reporting instead of merely an increase in the number of respondents who preferred not to disclose their ethnic or racial information. For example, the decrease in reporting could stem from unclear questions or insufficient options that fail to reflect how some participants self-identify. This issue should be resolved in the future, as accurate data on the racial and ethnic composition of apprentices are necessary to conduct an equity analysis.

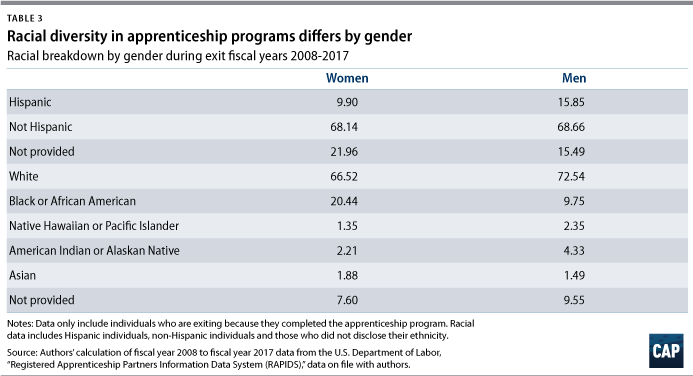

The gender composition of apprentices also varies by race and ethnicity. Black or African American women are much more likely to participate in apprenticeship programs than are black or African American men, while white, American Indian/Alaskan Native (AIAN), Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, and Hispanic/Latina women are less likely to be apprentices than are their male counterparts. There are minimal differences in participation rates by gender among Asian apprentices.

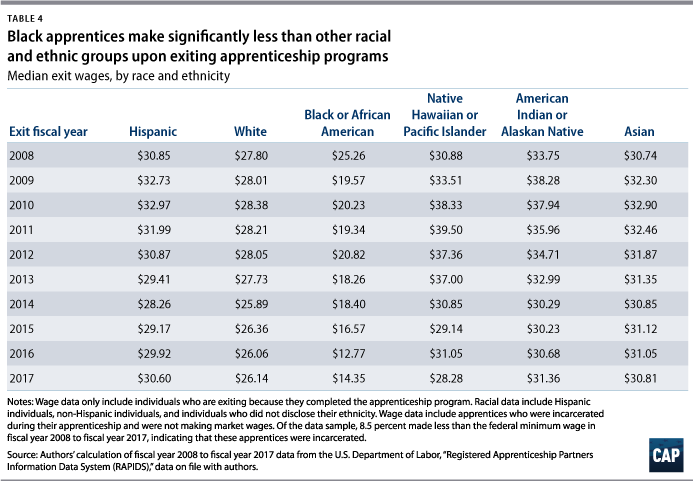

Black or African American workers make the lowest wages of all apprentices

Black or African American apprentices had the lowest exit wages of all racial and ethnic groups examined, at $14.35 per hour in fiscal 2017. White apprentices had the second-lowest earnings at $26.14—still more than 50 percent greater than black or African American apprentices’ wages. Median exit wages for completing apprentices were highest for AIAN, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islanders, Hispanic/Latino, and Asian apprentices—all of whom earned around $30 per hour.

One of the reasons that wages for Hispanics/Latinos, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islanders, AIAN apprentices, and Asians are so much higher may be that they are more likely than black or African American and white apprentices to complete their apprenticeship programs in the West. From fiscal year 2008 through fiscal year 2017, exit wages for apprenticeship programs were highest in the West at $32.50 and lowest in the South at only $20.80. While nearly 90 percent of Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander apprentices completed their apprenticeship programs in the West in this time period—as did 63 percent of Hispanics/Latinos, 86 percent of AIAN apprentices, and 73 percent of Asians—25 percent of whites and 40 percent of blacks or African Americans completed their apprenticeship programs in the South.

Additionally, black or African American apprentices are most likely to complete their programs while incarcerated, likely contributing to their lower median wages. Twenty-five percent of black or African American apprentices who have completed their program make less than the minimum wage—compared with only 7 percent of white apprentices—indicating that they are incarcerated, as federal law requires that all other apprentices make at least the federal minimum wage.20 Less than 4 percent of Hispanic/Latino, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, AIAN, and Asian apprentices made less than the minimum wage from fiscal year 2008 to fiscal year 2017.

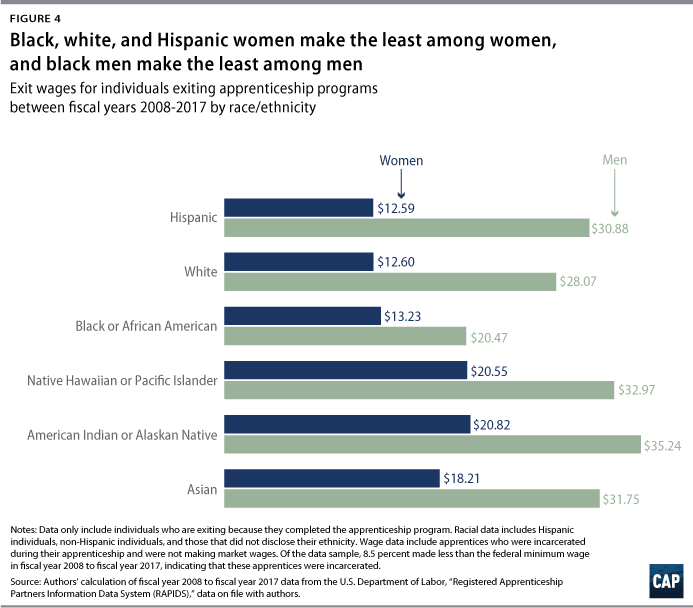

Wages also differ by gender across races among those who complete apprenticeship programs. Black or African American; white, and Hispanic/Latina women earn the lowest wages overall, and their wages are significantly lower than those of women of other groups. Additionally, black or African American men earn significantly lower wages than do men of every other racial/ethnic group.

Recommendations

Apprenticeship programs can and should be a broadly accessible path to good jobs that pay decent wages. However, currently, too many workers—particularly women and black or African American workers—face difficulties accessing these programs, especially the programs that pay the highest wages. As policymakers continue to make investments necessary to grow apprenticeship programs, their policies must center around women, people of color, and other underrepresented groups to ensure equitable access. Policymakers can help facilitate that access by continuing to support equity intermediaries and other workforce intermediaries that can help with recruitment and the coordination of supportive services such as child care, transportation, and legal assistance. The Center for American Progress has called for investments in labor management-led intermediaries that can fill this role.21

Policymakers should also work to eliminate occupational segregation in apprenticeship programs, as well as ensure that women and people of color have access to apprenticeship programs in the highest-paying occupations. This analysis shows that gender wage gaps narrow significantly when women have access to male-dominated apprenticeship programs. Policymakers should also ensure that apprenticeship programs are required to comply with the Davis-Bacon Act and support wage progression. These policies help ensure that the highest-wage programs remain well-paying.

Furthermore, policymakers should seek to expand apprenticeships into new industries, while working to raise the wages in those industries. For example, child care and hospitality apprenticeships are popular among women, yet both industries are plagued by persistently low wages. It is not enough to expand apprenticeships into new industries; wages in historically undervalued occupations dominated by women must be raised as well. Policymakers should also ensure that incarcerated apprentices are paid at least the federal minimum wage, which can help reduce recidivism and facilitate re-entry.22

Finally, policymakers should focus on implementation and enforcement of the 2016 EEO regulations and resist efforts to weaken the labor standards governing apprenticeship programs.

Conclusion

Apprenticeship programs equip workers with valuable in-demand skills and allow them to learn on the job while earning a decent wage. Policymakers are right to invest in this strategy and encourage more employers across the country to use apprenticeship programs to fill their open positions. However, the analysis in this issue brief shows that ensuring racial and gender equity in apprenticeships must be a central concern of policymakers and employers as they take steps to expand these programs.

Angela Hanks is the former director of Workforce Development Policy at the Center for American Progress. Annie McGrew is a former research assistant for Economic Policy at the Center. Daniella Zessoules is a special assistant for Economic Policy at the Center.