Introduction and summary

Now in its eighth year, Syria’s civil war has drawn in more than a dozen external actors, spawned terrorist threats, undercut regional stability, and fostered blatant disrespect for human rights and the basic rules of war. The Syrian people have borne the most devastating consequences of this conflict, with more than half a million dead and 12 million driven from their homes since 2011.1 The Syrian regime led by Bashar al-Assad has perpetrated well-documented crimes against humanity, including mass imprisonment, indiscriminate bombing of civilian areas such as hospitals and schools, chemical weapons attacks, and the use of starvation as a weapon of war.

The Trump administration has failed to articulate a clear and consistent strategy to address these multiple challenges or advance U.S. interests and values. For example, President Trump has issued contradictory statements on Assad’s fate as well as the United States’ commitment to keeping troops in northeastern Syria. The ambiguity and lack of leadership have confused allies and partners and reduced U.S. influence in the region.2 A hasty withdrawal of U.S. troops from Syria would risk allowing the Islamic State (IS) to resurrect itself after a crippling defeat—almost exactly what then-candidate Trump accused former President Barack Obama of doing by leaving Iraq in 2011.3 Absent a credible diplomatic process, the Assad regime continues to grind forward on the ground, further entrenching Russian and Iranian influence and newly displacing tens of thousands of people—particularly in southern Syria.4

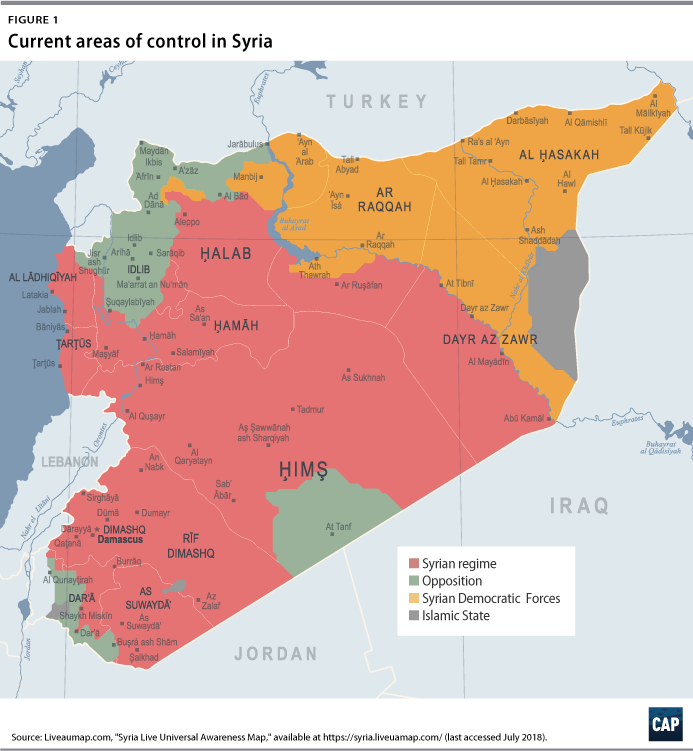

There are no good options in Syria, but there are better ones and worse ones. After years of suffering, Syria’s multiple conflicts have reached a crossroads. The Syrian regime has gained considerable ground. But rather than resulting in an Assad victory, the fighting has consolidated three de facto zones of control, each actively defended by an external power—Russia and Iran in the west, Turkey in the northwest, and the United States in the northeast. These zones have created pockets of stability that provide relative security for Syria’s beleaguered civilian population. Assad’s aspiration to retake all Syrian territory threatens this security. Equally worrisome, contested boundaries between the zones and the close proximity of U.S., Russian, and Turkish forces create a dangerous risk of wider escalation.

The United States has an opportunity to shape this emerging landscape in a way that advances American interests and values. Meeting these goals will require a new policy approach that better matches U.S. goals to U.S. resources and better mobilizes U.S. partnerships throughout the region.

This policy should prioritize de-escalating the conflict, stabilizing Syria’s periphery, and establishing a new diplomatic framework that tables Assad’s fate in favor of an intermediate agreement to separate forces on the ground. As a key part of this strategy, the United States should preserve the American-led military presence and accelerate stabilization efforts in the northeast. It should also leverage a firm commitment to defend this zone to engage Russia and Turkey in a new, U.N.-backed plan to end the fighting.

This approach is not without risks, but it offers key advantages over the course the United States is on today: It would allow the United States to responsibly conclude the campaign against IS. By freezing the conflict in place, it would prevent a murderous regime from exercising control over an entire population as well as halt the expansion of Russian and Iranian influence in the Middle East. And it would buy time for Syrians and the international community to seek a more durable national political settlement.5

This report highlights the U.S. interests and values at stake in Syria and presents the following four key components of a new strategy:

- Launch a new diplomatic initiative aimed at securing international recognition of de facto zones of control in Syria and renewing a national political process.

- Maintain the U.S.-led military presence in northeastern Syria to support this diplomatic initiative and ensure the lasting defeat of IS by continuing to partner with local forces.

- Expand stabilization assistance within the American-led zone of control, and press U.S. allies in Europe and partners in the region to do more.

- Sustain efforts to support Syrian refugees and shore up the stability of Syria’s neighbors.

This strategy would do more to advance U.S. interests than the alternatives currently under consideration inside and outside the Trump administration. Rash disengagement or the reckless escalation of military and economic pressure on Assad and his regional backers would be the wrong course of action.6

A rapid withdrawal of U.S. troops, which President Donald Trump has casually and publicly considered,7 would sell out the United States’ Kurdish and Arab partners and risk a slide into chaotic violence in eastern Syria that would give IS the opportunity to regroup and once again threaten the United States. It would also amount to the unilateral surrender of the leverage that the United States currently has over the Assad regime and its backers as a consequence of its presence in northeastern Syria, while receiving nothing in return and appeasing America’s geopolitical competitors and regional adversaries—namely Russia and Iran.

Pulling out U.S. troops in exchange for Russian President Vladimir Putin’s promises to roll back Iran’s current troop presence in Syria—as some have proposed8—would require America taking irreversible military moves upfront in exchange for vague and reversible pledges down the road that Moscow likely could not fulfill even if it desired to do so. Moreover, as Russia violates its previous cease-fire commitments with both President Trump and the Jordanian government through its bombardment of southern Syria, there is little reason to believe Putin would keep his word.

The other alternative—which some hawkish conservatives have proposed—would involve ratcheting up economic sanctions and the threat of military strikes against the Syrian regime as part of a broader effort to counter Iranian influence in the region.9 Taking this path would risk expanded fighting and a confrontation with Russia while offering no credible theory of success short of a costly and highly unpredictable war.

The U.S. interests and values at stake in Syria

Over the past several weeks, the Trump-Putin meeting in Helsinki, the North Korea summit, President Trump’s trade wars, and tensions between the United States and other Group of Seven and North Atlantic Treaty Organization countries have overshadowed news coverage of Syria’s civil war.10

The war, however, continues to have tremendous repercussions well beyond the country’s borders. Nowhere else do U.S. and Russian military forces conduct combat operations in the same theater, raising the risk of inadvertent escalation through miscalculation or error. The Syrian regime’s repeated use of sarin and chlorine has undermined global norms on the use of chemical weapons. And the conflict has produced ugly new political dynamics that have altered the course of politics in the United States and Europe. For example, the European far right exploited the 2015 wave of refugees from Syria to successfully spark xenophobic anti-immigrant populism and anti-establishment anger. It also provided the pretext for anti-Muslim bigotry to move from far-right fringe movements directly into the corridors of power in the United States and parts of Europe.11

These new political dynamics have revived a long-dormant approach to security in the United States and parts of Europe—inspiring those in power to build walls, halt immigration, and prioritize narrow counterterrorism operations rather than try to resolve endemic conflict through fostering the development of more open and prosperous societies.12 Syria’s festering conflict has contributed to this weakening of the international system.

From a security perspective, Syria’s civil war presents multiple risks that could lead to a wider geopolitical conflagration, including:

- Unintended escalation between the United States and Russia: Neither the United States nor Russia seeks a direct military confrontation in Syria, but a miscalculation or battle between partner forces on the ground—such as the February 2018 episode in which a Russian mercenary group attacked U.S. and partner positions in Deir ez-Zor13—could easily spiral into a broader conflict.

- A new war between Israel and Iran and Hezbollah: To protect its own security, Israel has repeatedly taken military action against Iranian and Hezbollah positions in Syria over the course of the civil war.14 Any number of developments—such as the deployment of heavy weapons systems or moves to establish Iranian positions close to the Israeli border—could trigger a war between Israel on the one hand and Iran and its proxy Hezbollah on the other.

- Confrontation between the United States and Iran: The Trump administration has consistently viewed Syria as an arena for competition with Iran, with U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo recently demanding that Tehran withdraw its forces from the country.15 With both Iranian and U.S. forces operating in Syria, a military incident between the two countries could easily undermine U.S. interests elsewhere in the region, including in Iraq and the Persian Gulf.

- Clashes between Turkey and Syria’s Kurds, with the United States caught in the middle: Turkey opposes America’s military partnership with the multi-ethnic but Kurdish-dominated Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). An agreement for joint Turkish-American patrols in the Syrian city of Manbij has eased tensions, but Turkey continues to threaten further attacks on SDF-controlled territory where U.S. forces are currently deployed as part of the campaign to counter IS.16

As long as the fighting continues, and as long as Syria remains a battleground for competing global and regional powers, there is significant risk for a major geopolitical escalation. U.S. interests in Syria cannot be separated from these broader strategic considerations. The United States has the following four main interests at stake in Syria:

- Prevent terrorist attacks against the United States and its allies.

- Prevent a broader geopolitical escalation that could draw the United States further into the Syrian conflict or imperil U.S. allies and partners.

- Limit the expansion of Russian and Iranian influence in the Middle East.

- Alleviate the suffering of the Syrian people and increase protections against Assad’s crimes against humanity and other violations of the rules of war.

The Obama administration largely succeeded in countering the IS threat that emerged on its watch, but it was unable to advance a strategy to end the civil war, contain its negative effects on regional security, or effectively protect Syrian civilians. Although President Obama called for Assad to step down as part of a negotiated political transition,17 his administration did not assemble the policy tools needed to make that a reality.

President Trump’s approach to Syria has been utterly erratic and incoherent. His administration has issued contradictory statements on whether Assad’s removal is a condition for a political settlement and flip-flopped on whether it plans to keep approximately 2,000 U.S. forces in northeastern Syria.18 President Trump has twice ordered strikes against the Assad government for its continued use of chemical weapons without meaningfully connecting the use of force to any broader set of strategic objectives.19 In southern Syria, for example, the administration negotiated a cease-fire agreement with Russia and Jordan but then failed to guarantee it in the face of a renewed Russian-backed regime offensive.20

This policy incoherence puts U.S. military forces inside Syria at greater risk. It benefits America’s global and regional adversaries, including Russia and Iran, by ceding the strategic initiative to them while undercutting the security of close partners such as Israel and Jordan. Indeed, Russia has gained diplomatic leverage across the Middle East as a result of its intervention in Syria.21 There may be no perfect option for the United States in Syria, but a better course is available—even if the Trump administration seems unlikely to take it.

A new policy framework for Syria

To de-escalate Syria’s civil war and advance U.S. interests both in the country and across the wider region, the United States should pursue the following four lines of effort: 1) Launch a diplomatic initiative aimed at securing international recognition of de facto zones of control in Syria and renewing a national political process; 2) Maintain the U.S.-led military presence in northeastern Syria to support this diplomatic initiative and ensure the lasting defeat of IS by continuing to partner with local forces; 3) Expand stabilization assistance within the American-led zone of control, and press U.S. allies in Europe and partners in the region to do more; and 4) Sustain efforts to support Syrian refugees and shore up the stability of key U.S. partners neighboring Syria.

1. Launch a diplomatic initiative aimed at securing international recognition of de facto zones of control in Syria and renewing a national political process

While the United States would undoubtedly like to see the Assad regime give way to a more open Syrian political system, it is time to recognize that this goal is not achievable in the short run at a cost acceptable to the American people. Regime change and the prospect of a long-term, open-ended commitment of U.S. ground forces are unacceptable to most Americans.22 A more realistic approach involves using U.S. influence to push relevant regional and international powers toward a solution that stabilizes existing zones of control where possible. This, in turn, would lay the foundation for a more comprehensive resolution of Syria’s internal conflicts down the road—a resolution that is based on the decentralization of power and authority.23 This approach does not directly address the regime’s record of crimes against humanity in the short term, but it may end the fighting by satisfying the most pressing concerns of each external actor now involved in Syria’s civil war.

At present, U.S. diplomacy mirrors the balkanization of the conflict itself. Talks with Russia, Jordan, and Israel focus on the deteriorating situation in southern Syria, while those with Turkey focus primarily on that country’s dispute with the SDF.24 At the same time, the United States remains invested in the stagnant and now largely irrelevant diplomatic process in Geneva that is focused on negotiations between the Assad regime and non-extremist opposition forces that have been all but wiped out.25 This U.S. approach is passive and reactive, and it cedes the diplomatic initiative to Russia—the one actor in Syria that diplomatically engages all parties. It also fails to leverage the United States’ indirect control over a significant proportion of Syria’s agricultural and energy resources to entice Russia to re-engage in talks leading to a broader political settlement.

The immediate goal of a new U.S. diplomatic initiative would be to prevent wider geopolitical escalation by securing international recognition of zones of control on the ground in Syria and initiating a process to clearly demarcate their boundaries. Mutual agreement on boundaries would lay the ground rules for the military operations of all parties in Syria, with Russia, Turkey, and the United States acting as guarantors. Joint military patrols or other mechanisms could then be established to reduce the risk of miscalculation and discourage cross-boundary attacks. Talks could also explore ways to ensure the delivery of humanitarian relief to areas in need throughout Syria.

In practice, this strategy would require the United States to engage in tough trilateral diplomacy with Russia and Turkey as well as work with the United Nations to sketch out a framework that could be enshrined in a new U.N. Security Council resolution. The failure of the July 2017 cease-fire deal between the United States, Russia, and Jordan26 to stop regime and Russian offensive military operations in southern Syria amply demonstrates that, to succeed, any agreement would need to enjoy broader international recognition and be backed by the credible use of force.

Russia would need to be convinced that the United States would defend eastern Syria and that this zone would be reintegrated into the rest of the country only as part of a diplomatic process that extracted meaningful political concessions from the Assad regime—especially political and administrative decentralization and the reduction of presidential powers. Turkey would need to be given a veto over the potential creation of an independent Kurdish state on its border. Throughout the diplomatic process, the United States would need to actively consult its European allies and regional partners, including Israel and Jordan, and maintain an indirect but open channel to Iran.

This would yield a map divided into three zones:

- Western Syria would be controlled by the Syrian regime, backed by Russia and Iran, and extend from the Jordanian border to Aleppo and from the Lebanese and Israeli borders to the west bank of the Euphrates River.

- Northern Syria would be controlled by opposition groups, backed by Turkey, and include northern Idlib and parts of Aleppo provinces. It would be bounded to the east by the line that Secretary Pompeo and his Turkish counterpart Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu negotiated in early June 2018.27

- Eastern Syria would be controlled by the SDF, backed by the United States and its allies, and bounded by the Turkish and Iraqi borders and the west bank of the Euphrates River. This is consistent with the deconfliction line that the United States and Russia agreed to in August 2017.28

While several of these boundaries are already fairly clear, negotiations would need to resolve the boundary between regime- and Turkish-controlled territory in northern Syria, including the fate of opposition and extremist groups in Idlib province.

In exchange for a nationwide cease-fire, the United States should offer its tacit acceptance that Assad will not be removed from power in the near future. It should also replace or restructure talks in Geneva with a new U.N.-backed forum to negotiate the country’s political future. Discussions over the phased withdrawal of foreign forces from Syria—a key requirement of the Assad regime, Israel, and other countries—should begin in parallel with talks aimed at ending the conflict.

This approach would not constitute a formal partition of the country, which Syrians and many states in the region, including Turkey, vehemently oppose. Rather, it would recognize and seek to capitalize on the reality that the conflict has created—that external actors now exercise control over relatively coherent blocs of Syrian territory. Combined with an offer of a short-to-medium-term accommodation, this short-term necessity would help reconcile these actors’ core interests and reduce the risk of geopolitical escalation inherent in the current competition for influence and territory in Syria. As conditions shift, additional sustained diplomatic work will be required to prevent formal partition and find a lasting political solution that maintains the country’s unity and territorial integrity.

This framework could satisfy the interests of Assad’s backers in keeping his regime in power—a bitter pill for many Syrians, given his crimes—while satisfying U.S. interests in ending the fighting, reducing the risk of escalation, and creating a more stable environment in which to finish the military campaign against IS. And while this strategy cannot eliminate Iranian influence in Syria, it could help isolate Iran diplomatically by shifting security discussions away from Russian-sponsored talks in Astana, Kazakhstan, where Tehran has a front-row seat.29 Moreover, it could help eliminate the underlying rationale for Iranian and Hezbollah involvement in Syria.

2. Maintain the U.S.-led military presence in northeastern Syria to ensure support for the new diplomatic initiative and the lasting defeat of IS by continuing to partner with local forces

Right now, the primary mission of U.S.-led military forces in northeastern Syria is to eliminate the remnants of IS and prevent its rebirth by advising, assisting, and accompanying the SDF and affiliated local security forces.30 This mission remains critical to U.S. national security and should continue until the IS threat has been neutralized, as President Trump has indicated it will.31

As part of this mission, U.S. forces have taken up positions between the SDF and Turkish-backed opposition groups near Manbij in order to prevent a confrontation between the two forces—a confrontation that would detract from the mission of defeating IS. U.S. forces also play a role in deterring the Assad regime and its allies from attempts to retake territory east of the Euphrates River. U.S. troops on the ground have already blunted one Assad regime attempt to reclaim territory in Syria’s northeast by calling in strikes on pro-regime columns advancing on their positions in Deir ez-Zor.32

The Trump administration and Congress should work together to provide the necessary authorization for these multiple missions. In parallel, a U.N. Security Council resolution that ratifies a diplomatic agreement negotiated between the United States, Turkey, and Russia would provide a solid international legal basis. If the U.S. government cannot secure such a resolution or the cooperation of its partners, it should outline its own view on how these military operations align with international law.

The United States, however, should not shoulder these responsibilities alone. British and French troops already serve on the ground in northeastern Syria alongside their American allies,33 and the United States should seek out additional help from its long-standing military partners in Europe and the region. Ongoing cooperation between the United States and the Iraqi military to conduct operations against IS in Syria should also continue and be expanded where possible.

In principle, President Trump’s instinct to seek troop contributions and financial help from America’s regional partners for this mission is not misguided. The Trump administration has asked for $4 billion from Saudi Arabia for stabilization efforts, as well as troops from Egypt, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates to replace U.S. forces on the ground.34 Yet it is unclear why these partners would make such commitments, especially without assurances of at least some U.S. military and financial participation.

Convincing U.S. allies and partners to do more will require aggressive diplomacy—an area where the Trump administration does not have a sterling track record. That President Trump has fanned the flames of divisions within the Gulf and denigrated and alienated European allies also does not help matters.35 The Trump administration has yet to prove that it can leverage U.S. power and influence in the Middle East in ways that actually advance U.S. interests and yield sustainable results on the ground. With more active American leadership and a clearer connection between its counterterrorism and diplomatic goals, the United States would be in a much stronger position to amplify the impact of its own modest investments in northeastern Syria.

3. Expand stabilization assistance within the American-led zone of control and press U.S. allies in Europe and partners in the region to do more

Areas liberated from IS and held by the SDF or U.S.-backed local security forces will require significant stabilization assistance to provide basic services and jump-start wider recovery efforts. After nearly two decades of war in Afghanistan and Iraq and given domestic economic challenges, it is understandable that the American people might look askance at funding reconstruction abroad.36 But the Trump administration’s approach—freezing and then canceling planned aid—will cost the United States far more over the long-term, especially if IS regroups and regenerates its ability to threaten the United States.

Together with its allies and regional partners, the United States should organize a robust stabilization program for northeastern Syria that is focused on immediate recovery, the provision of humanitarian assistance, the restoration of basic public services, and training for local police. Such a program would help liberated areas recover from the fight against IS and provide a concrete demonstration of the benefits of U.S. partnership.

These stabilization programs will be more effective with American involvement to direct and monitor the provision of assistance. Equally important, however, is to guard against the sort of free-for-all competition among regional powers that the world has seen in Libya and Yemen.37 Without an American stake in stabilization, no other nation is likely to step in and get northeastern Syria up and running again and thereby deny IS and other extremists fertile ground to recruit. In the wake of U.S.-led counterterrorism operations, this is both a moral responsibility and sound strategy.

4. Sustain efforts to support Syrian refugees and shore up the stability of key U.S. partners neighboring Syria

The United States should continue to provide humanitarian assistance to Syrian refugees and support the stability of its regional partners who bear the brunt of the Syrian conflict’s multiple spillover effects. First and foremost, the United States should increase the amount of aid provided to countries such as Jordan and Lebanon to help them cope with proportionally large Syrian refugee populations. The United Nations’ most recent Regional Refugee and Resilience Framework requires some $5.6 billion to fund assistance efforts for Syrian refugees and the governments that host them across the Middle East.38 International donors have provided just more than a third of this request, and the United States has provided 6.8 percent of this funding. Right now, Saudi Arabia has contributed slightly more than $930,000 to this campaign, while the United Arab Emirates has contributed just less than $100,000.39 The United States should substantially increase its contribution to this effort—and challenge its regional partners to match its contribution.

A durable cease-fire in Syria will go a long way toward stabilizing the Levant more broadly. In the meantime, however, the United States can bolster the ability of its partners in Israel and Lebanon to withstand the security challenges arising from Syria’s civil war. In particular, the United States should maintain its material support for the Lebanese Armed Forces as it confronts IS cells in Lebanon. Washington can also work politically and diplomatically with regional partners such as Saudi Arabia to counter Iranian influence in Lebanon—especially after Lebanon’s parliamentary elections marginally increased the power and influence of Hezbollah.40

Israel remains capable of defending its own security and protecting its own interests in the region. But the United States should help Israel seek strategic alternatives to a sustained military campaign against Iranian and Hezbollah positions in Syria that could spark a wider conflagration. Recent rumors of a deal between Israel and Russia to limit Iranian and Hezbollah deployments along the Israeli border41 may be worth exploring in the context of wider diplomatic talks involving the United States. Such a deal may not hold, but it is worth trying given the paucity of realistic alternatives.

Conclusion

The Trump administration’s contradictory strategy and lack of leadership in Syria promises more bloodshed and displacement. It risks enabling an IS resurgence that would reverse four years of hard-won gains by the U.S. military and gives the Assad regime a license to continue its assault on the Syrian people. As a consequence of the multiple foreign forces now operating inside the country, it also leaves significant room for a miscalculation that could badly inflame regional and international tensions. President Trump’s approach will fail to achieve even the administration’s primary stated goal of limiting Iran’s influence in the region.42

The United States cannot solve all of the challenges that Syria’s civil war presents. But the current consolidation of zones of control presents a diplomatic opportunity that the United States should seize to de-escalate the conflict and restart a political process. As a result of the U.S.-led coalition’s successful campaign against IS and its military presence in the northeast, the United States has limited but important influence over the course of Syria’s civil war. A coherent and consistent American policy similar to the one outlined in this report could leverage this influence to seize the diplomatic initiative.

While President Trump will likely not pursue this approach—securing international recognition of de facto zones of control in Syria; maintaining the U.S.-led military presence in northeastern Syria; expanding stabilization assistance within the American-led zone of control; and sustaining efforts to support refugees and shore up the stability of key U.S. partners neighboring Syria—it represents the best available option for the United States to advance its interests and values in Syria.

About the authors

Brian Katulis is a senior fellow at American Progress, where his work focuses on U.S. national security strategy and counterterrorism policy. His past experience includes work at the National Security Council and the U.S. Departments of State and Defense during the Clinton’ administration. He also worked for Greenberg Quinlan Rosner Research, the National Democratic Institute for International Affairs, Freedom House, and former Pennsylvania Gov. Robert Casey (D). Katulis received a master’s degree from Princeton University’s Woodrow Wilson School for Public and International Affairs and a B.A. in history and Arab and Islamic Studies from Villanova University.

Alexander Bick is a research scholar at the Henry A. Kissinger Center for Global Affairs at Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies. He previously served in the Obama administration as director for Syria at the National Security Council and on the secretary of state’s policy planning staff. He earned his Ph.D. in history from Princeton University.

Peter Juul is a senior policy analyst at the Center for American Progress, where he has worked on Middle East policy and U.S. national security strategy for more than 10 years. He holds a bachelor’s degree in international relations and political science from Carleton College in Northfield, Minnesota, and a master’s degree in security studies from Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service. His work has appeared online in Wired, Aviation Week and Space Technology, the Philadelphia Inquirer, and other publications.

Daniel Benaim is a senior fellow at the Center for American Progress and a visiting assistant professor at New York University’s Program in International Relations. He previously served as a Middle East adviser and speechwriter in the Office of the Vice President, on the secretary of state’s policy planning staff, and on the professional staff of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. He was awarded an International Affairs Fellowship at the Council on Foreign Relations. Benaim has an undergraduate degree in English literature from Yale University and a Master of Arts in law and diplomacy from the Fletcher School at Tufts University.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank their former CAP colleague Alia Awadallah for her early work on what became this report; Rudy deLeon, Gordon Gray, Max Hoffman, Kelly Magsamen, Minna Jaffery, and the rest of the CAP National Security and International Policy team for their feedback throughout the writing process; and Prem Kumar, Hardin Lang, Rob Malley, Salman Ahmed, David Adesnik, and Michael O’Hanlon for reviewing later drafts.