Since 2011, social impact bonds have moved from concept to execution in the United States. These bonds, known as SIBs, are innovative financing tools for social programs: Private investors pay the upfront costs for providing social services, and government agencies repay the investors with a return—if and only if a third-party evaluator determines that the services achieve agreed-upon outcomes.

These agreements may be a viable source of expanding support for preventive interventions that could both demonstrably improve social outcomes and save cash-strapped governments money on later remedial services. When think tanks, government agencies, investors, service providers, and other groups began considering whether social impact bonds could work in the United States, there was only one such deal underway: the HM Peterborough Prison social impact bond, which aims to reduce recidivism among inmates released from a facility some 90 miles north of London, England. Since then, New York City; Salt Lake City, Utah; New York state; and Massachusetts have all launched SIBs in the United States, and about 12 other states are known to be actively considering entering into these or other so-called Pay for Success agreements.

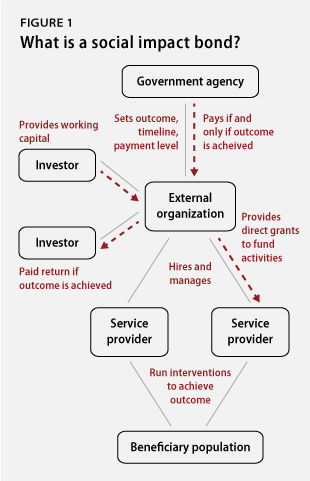

In the classic, Peterborough-style social impact bond, a government agency sets a specific, measurable social outcome they want to see achieved within a well-defined population over a period of time. In Peterborough, for example, that agency was the U.K. Ministry of Justice, and the outcome was at least a 7.5 percent reduction in recidivism among nonviolent, short-term prisoners. The government then contracts with an external organization—sometimes called an intermediary—that is in charge of achieving that outcome. In Peterborough, that intermediary is the ONE Service, a special-purpose entity run by Social Finance UK. The intermediary hires and manages service providers who perform the interventions intended to achieve the desired outcome. Because the government does not pay until and unless the outcome is achieved, the intermediary raises money from outside investors. These investors will be repaid and receive a return on their investment for taking on the performance risk of the interventions if and only if the outcome is achieved. Again, in the Peterborough agreement, the investors were primarily socially minded trusts and foundations.

But trusts and foundations are by no means the only potential investors for social impact bonds. The SIB trend is one development in the larger field of social finance, in which so-called impact investors seek blended social and financial returns, or what are often called double-bottom-line returns on their investments. Impact investors include individuals with high net worth who want to make more sustainable, responsible investments. They also include both small investment firms dedicated to impact investing as well as large financial institutions with community development divisions. And they include Community Development Financial Institutions, or CDFIs, which have made a wide range of investments in underserved communities for decades. Finally, foundations and trusts can be impact investors too. Many foundations have taken a pioneering lead in building the social finance field, from providing grants for research, education, and technical assistance to investing in individual transactions.

Social impact bonds are complex arrangements that require trusting relationships between a range of public, private, and nonprofit actors. But there is also considerable variation within each category of organization working on a SIB transaction. Foundations, CDFIs, individual impact investors, and large financial institutions have considerably different appetites for risk, as well as different organizational cultures, different expectations of return on investment, and different motivations for considering investing in a given social impact bond transaction. All of these factors mean that different investor types are likely to behave differently if they were to co-invest in a larger or more complex social impact bond transaction.

That’s why in 2013, the Center for American Progress and the Council on Foundations jointly organized two roundtable conversations with potential social impact bond investors, bringing together representatives from foundations, CDFIs, and impact investment firms to discuss how each sector might envision participating in a social impact bond transaction. A limited number of representatives from the federal government and from intermediary organizations also attended the meetings. We partnered with Steven Goldberg, an independent social finance consultant, to produce two hypothetical investment cases. In each case, we made deliberate choices to vary the level of evidence for the proposed intervention, offered rates of return derived from government savings that would be realized over different time frames, and offered information about provider readiness and government actions to support social impact bonds.

Our process in designing these two roundtable discussions is explained in detail in an issue brief released jointly with the Council on Foundations, “Networking for Success: Building Networks Essential to Investment in Social Impact Bonds.” Our intention in writing the investment cases was to try to elicit comments from different investor types reflecting on how institutions like theirs might approach co-investing in such transactions. At the time, the only active SIB in the United States was a deal targeting juvenile recidivism in New York City, in which $9.6 million in investment from Goldman Sachs was guaranteed with a $7.2 million grant from Bloomberg Philanthropies—ensuring that, even if the outcome were not achieved, Goldman Sachs was not risking most of its capital. This was quite different from the all-or-nothing investment in the Peterborough social impact bond; we thought that offering hypothetical investment cases might free up different investor types to explore where they felt it would be most appropriate for foundations, CDFIs, investment firms, and so on to participate in the capital stack of a complex social impact bond transaction.

Investment case studies

Using social impact bonds to prevent child abuse and neglect

The scenario: We proposed a $20 million social impact bond to prevent the children of 2,500 families from entering foster care over a period of five years, with a proposed intervention that was termed “promising” but had not yet been determined to be a “gold-standard” or a “top-tier” evidence-based intervention. In this situation, the cost of foster care for the state in 2011 was $111 million and resulted in 2,700 placements. It is estimated that reducing the need by the level mentioned above would save the state $54 million over five years. Depending on the terms of the deal and its successful outcome, the investors would be repaid their capital investment plus 5 percent or 10 percent of the state’s savings, for a return of $1.6 million or $4.3 million.

Using social impact bonds to fund early childhood education

The scenario: We proposed scaling high-quality, early childhood classroom instruction, which is considered a top-tier evidence-based practice, for 5,000 low-income 3- and 4-year-olds in a state that did not currently have a state-funded public pre-K program. The program cost was $60 million over seven years. In this situation, a cost-sharing agreement between the state and federal governments was proposed to repay an investment size of $47.5 million, with a potential return on investment of 5 percent, or $2.25 million.

The roundtables raised a wide range of important issues from the investor perspective, from the crucial need to build networks and relationships between different investors and across sectors to a range of policy and research questions. We consider the importance of interorganizational relationships in “Networking for Success.” This issue brief focuses on the policy issues discussed in both meetings and also reflects on some of the questions that the investor community needs to consider as the social impact bond market continues to develop. As a result, the issue brief is not intended to be a comprehensive overview of the policy, research, or technical assistance needs of the social impact bond sector or the investor community; however, the views shared in the meetings do offer valuable insight into some investor concerns.

Since the time of the meetings, SIBs have been launched in Salt Lake City, New York state, and Massachusetts. Each of these has had more complex investment structures than the New York City bond, and in each transaction, the institutional investors involved have taken on more and more risk. These developments show that this is a dynamic and evolving market, and these reflections on our two roundtable discussions should be understood within that context.

Policy needs identified by participants

Mitigate uncertainty and manage or share risk

Both groups focused on the risks in the two investment cases, and reflected on the difference between risk and uncertainty. All investments come with risks, and one of the benefits of social impact bonds to government is that there is a degree of risk transference—if the program does not perform, the government is not on the hook financially. But in these early days, the SIB market faces a lot of uncertainty as well. Different state and local governments have taken different steps to mitigate uncertainties such as appropriations risk—the danger being that, absent legal requirements, a future legislature or administration may fail to appropriate funds to repay a successful social impact bond transaction. Of course, until social impact bonds have been tested more thoroughly, there is a limit to how much government or any other actor can do to reduce uncertainty.

Both groups also asked whether there was a way for government to more actively share risk. This was partly motivated by a sense that the returns on offers in the hypothetical cases were too low for the level of investment and anticipated government savings but also reflected a broader structural concern. To the investors in the room, the government was “free riding” in the hypothetical cases, reaping most of the savings and benefits while shouldering none of the risk. This position omits the fact that governments in social impact bond transactions are taking on significant reputational risk, especially in early deals, should anything go awry. However, it is worth investigating appropriate ways for government to have more “skin in the game” in future social impact bond transactions.

Consider lessons from existing social impact vehicles and programs

Many participants expressed the need to carefully examine and learn from existing policy tools that drive social impact investing, including the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit, which helps subsidize the construction of housing for low-income families; the Community Reinvestment Act, which encourages commercial banks to invest in low-income communities; and the Community Development Financial Institution Fund, which helps provide capital to CDFIs. Not all lessons will be applicable to the SIB market, however. For instance, the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit is run through the tax code, while social impact bonds, as currently envisioned, will be paid for through the appropriations process, which can be more unpredictable.

But the lessons of past financial innovations can offer important guidance as the federal government considers how best to support the SIB market. Indeed, the Obama administration’s fiscal year 2014 proposal to create a $300 million incentive fund to support “Pay for Success” transactions at the Treasury Department could take lessons from the implementation of the Community Development Financial Institution Fund.

Have a deeper conversation about social impact bond applications

Debate was heated at both meetings about the investment case that proposed a social impact bond to reduce the number of foster care placements. Some investors worried about perverse incentives, such as service providers feeling pressured to keep kids in dangerous situations. Others voiced concern about increased reputational risk if they invested in a deal in which any of the children came to harm. Still others objected to the proposed model of the intervention, which paired the nongovernmental service provider with the state child services agency on inspections of at-risk home situations.

In the United Kingdom, however, one ongoing social impact bond focuses on teenagers who are at risk of entering foster care; its example indicates the tool may be used to fund a similar effort in the United States at some point. What the conversations made clear is that significantly more work still needs to be done to educate potential investors about the risks and rewards of getting involved in different social service areas and to build up legal standards for ensuring the population being served is sufficiently protected from harm.

Follow-up processes after transactions conclude

Representatives from all investor types raised questions about what the plans were for continuing services or raising additional investments beyond the terms of the hypothetical cases. Some questioned whether social impact bonds on their own would be enough to prompt sustainable, systemic change in how we prioritize, fund, and evaluate social services from a government perspective. Others wanted lower or shared investor risk as a method of encouraging repeat investment and replicable transactions. Still others pointed to the tension between funding interventions with high levels of evidence of success, as is the case with many early social impact bonds, versus using these bonds to fund riskier or more innovative programs.

Given that we convened these meetings to discuss what would prompt investors to enter into a social impact bond, the concern about what happens after the end of a social impact bond was somewhat unexpected. However, there is clearly a need for more research on these questions as more transactions are funded and begin to demonstrate results.

Conclusion

The conclusions drawn from these meetings are based on a small sample size, but in spite of the limited number of participants, the two sessions led to energetic, wide-ranging, and spirited conversations among a diverse range of potential and active social impact bond investors. As the SIB field develops, these and other debates will continue, and more questions are likely to be raised. But improving relationships and building networks between investor types and other sectors involved in social impact bond transactions will certainly help determine answers to these and other issues.

Kristina Costa was a Policy Analyst in economic policy at the Center for American Progress at the time of the drafting of this brief.