This fact sheet contains a correction.

Bisexual people are the invisible majority of the LGBTQ community. About half of all people in the LGBTQ community identify as bi+, meaning they identify as bisexual, queer, pansexual, or some other identifier indicating attraction to more than one gender.1 The lack of data on sexual orientation continues to be a challenge, and the few sources that do gather this data often group bi+ people together with gay and lesbian respondents. Disaggregating the data fosters better understanding of bi+ people’s experiences and needs.

New analysis of nationally representative survey data from the Center for American Progress finds differences between bi+ and monosexual—gay, lesbian, or straight—respondents.2 Across a variety of measures, bi+ survey respondents reported worse outcomes compared with monosexual respondents of the same gender. Many of the differences found in this study were not statistically significant, though this may be due to the small sample size. (see Methodology) Additional research would further our understanding of these relationships.

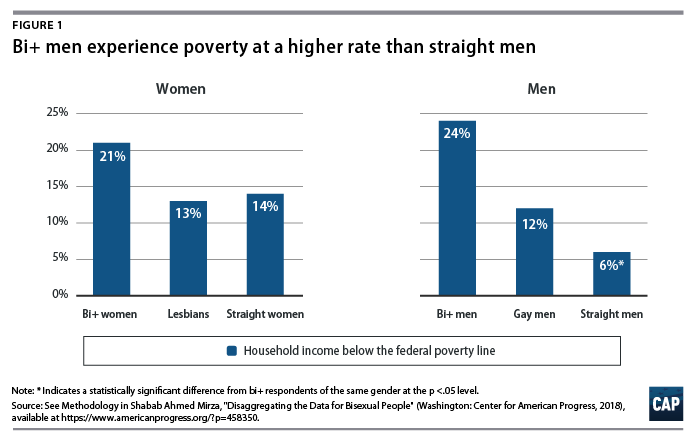

Bi+ men were four times as likely to report living in poverty compared with straight men, in line with previous studies on differences in income for bisexual people.3

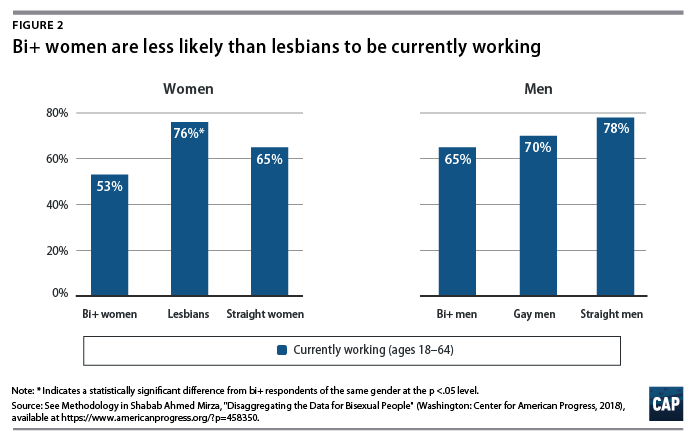

Bi+ women were less likely to report that they were currently working compared with lesbians. Prior research on workplace discrimination often grouped lesbian and bi+ women together, which may have obscured differences between these two groups.4

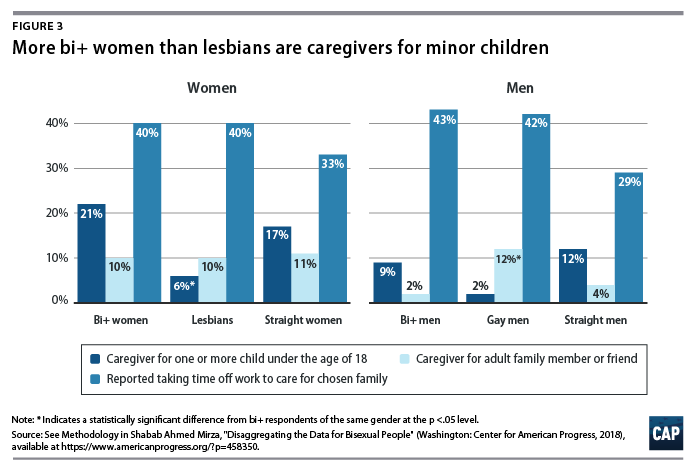

While same-sex couples are less likely to be raising young children, this is not necessarily true for all LGBTQ people.5 There were no statistically significant differences in caring for young children between bi+ respondents and straight respondents of the same gender. Bi+ women were nearly four times as likely to be caregivers for minor children compared with lesbians. About 1 in 10 women were caregivers for adult family members or friends, with no differences across sexual orientation. Bi+ men were six times less likely to be caregivers for adult friends or family compared with gay men, though both these groups of men reported taking time off work to care for chosen family at similar rates.

Bi+ women and their families are more likely to depend on the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and Medicaid than their monosexual peers. Thus, cuts to these programs could be especially harmful for them. This is in line with prior research indicating that bisexual women report food insecurity and SNAP participation at higher rates than monosexual women.6

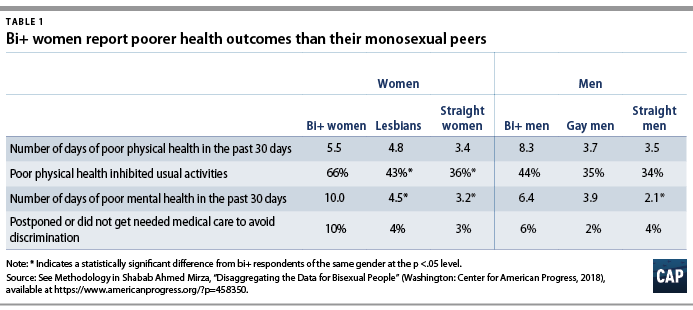

Bi+ men reported worse mental health outcomes than straight men, and bi+ women reported poorer outcomes than monosexual women for both mental and physical health. Prior research has linked coming out of the closet with more positive health outcomes, and bisexual people are less likely to have disclosed their sexual orientation to important people in their life than gay and lesbian people.7 This may explain some of the differences between bisexual respondents and gay and lesbian respondents.

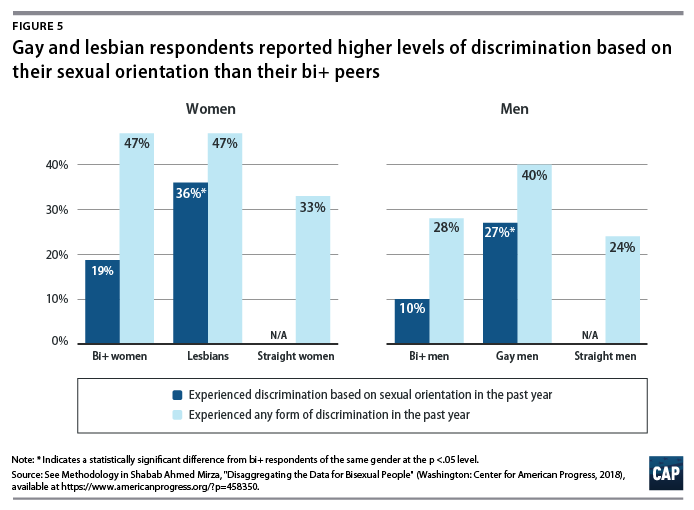

Fewer bi+ respondents reported experiencing sexual orientation discrimination compared with gay and lesbian respondents. Bi+ people may experience fewer acts of discrimination because they may be perceived as straight, are more likely to have different-sex partners, and are less likely to be out to friends and family.8

A note about bisexual erasure

Prior studies have linked discrimination with poor health outcomes for LGBTQ respondents. In this analysis, bi+ people were less likely to report experiences of discrimination than gay and lesbian people but were more likely to report poor health outcomes. Bi+ people may be less likely to experience enacted stigma, or unfair treatment, if they have a partner of a different gender or if they have not disclosed their sexual orientation to others. However, they may still experience felt stigma, such as feelings of shame or isolation, around their sexual orientation. They may be made to feel that their sexual orientation is not legitimate and that they must adhere to one of two monosexual identities, a phenomenon known as bisexual erasure.9 While LGBTQ social networks are a vital support for many gay and lesbian people, bisexual erasure may preclude bi+ people from fully participating in the LGBTQ community. Further research can help clarify how the gender of their partners, disclosure of their sexual orientation, and being perceived as straight affect the experiences of bi+ people.

Conclusion

The present data demonstrate that bi+ people’s experiences do not always align with their monosexual peers’. Disaggregating research on the LGBTQ community by sexual orientation can help health care providers, researchers, and policymakers design policies and resources that address the unique needs of bi+ people.

Shabab Ahmed Mirza is a research assistant for the LGBT Research and Communications project at the Center for American Progress.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Lauren Beach, Rasheed Malik, Heron Greenesmith, Lynette McFadzen, Emily Gee, and Laura Durso for their assistance with this fact sheet.

Methodology

To conduct this study, the Center for American Progress commissioned and designed a survey, fielded by GfK SE, which surveyed 1,864 adults, including 857 adults who identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual, and/or transgender, queer, or asexual and 1,007 who identified as heterosexual and cisgender/nontransgender. The data are nationally representative and weighted according to U.S. population characteristics. After weighting, the sample size of all LGBTQ respondents was 135. Respondents came from all income ranges and were diverse across factors such as race, ethnicity, education, geography, disability status, and age. The survey was fielded online in English in January 2017. All comparisons presented with an asterisk in the figures and tables are statistically significant at the p < .05 level. Comparisons that were not found to be statistically significant do not have an asterisk.

The present analysis excludes genderqueer, gender nonconforming, nonbinary, and agender respondents, because the sample size for these groups was too low to compare across sexual orientations. “Women” includes respondents who identified as “female” or “trans female/trans woman,” and “men” includes respondents who identified as “male” or “trans male/trans man.”

Estimates for the percentage of people currently working and the percentage of people receiving benefits may differ from official statistics due to the way the information was collected and should not be compared directly. The disparities that this survey finds between bi+ and monosexual people would likely still hold.

Additional information about study methods and materials are available from the author.