In 2014, the Obama administration’s effort to clean up, fix, and modernize the federal government’s oil and gas leasing program on public lands will reach its most critical milestones since the Department of the Interior’s reform agenda launched in 2009. From tests of the administration’s signature oil and gas reforms to looming endangered-species decisions and overdue environmental protection rules, Secretary of the Interior Sally Jewell will have a full plate as she works to restore balance between energy development and the protection of land, water, and wildlife.

In this brief, we assess the long-term impacts of a controversial decision by the Bush administration—one that took place five years ago this week—to lease lands near national parks in Utah for oil and gas development. We present new public opinion data that provide greater detail on Americans’ current priorities for their public lands and help explain why the Utah leasing debacle in 2008 provoked such a strong public outcry.

In addition, we identify six areas to watch that, taken together, demonstrate the extent to which the Obama administration’s reforms to the nation’s oil and gas leasing program are resulting in meaningful and lasting changes in priorities, values, and decision making within the Bureau of Land Management, or BLM, the nation’s largest land-management agency. These areas are:

- The creation of Master Leasing Plans to guide drilling to the right places

- The revision of Resource Management Plans on 140 million acres of public land

- The progress of environmental protection rules for oil and gas extraction

- The development of a strong new policy to mitigate the impacts of oil and gas drilling

- The restoration of balance between oil and gas leasing and the permanent protection of public lands

- The protection of sagebrush habitat to alleviate drilling impacts on wildlife

The legacy of the 2008 Utah leasing debacle

When President Obama took office, the BLM’s oil and gas leasing program was in crisis. Just one month earlier on December 19, 2008, the Bush administration had auctioned off oil and gas leases on more than 103,000 acres of public land near Arches and Canyonlands National Parks, Dinosaur National Monument, Desolation Canyon, Nine Mile Canyon, and wilderness study areas in Utah.

The decision provoked a firestorm of opposition. The Salt Lake Tribune said the BLM acted with “blatant disregard for its mission to protect Americans’ special and irreplaceable lands.” A federal court agreed and, citing the “threat of irreparable harm to public land if the leases are issued,” granted a temporary restraining order blocking the BLM from moving ahead with the leases. Obama’s new Interior Secretary, Ken Salazar, ordered a top-to-bottom review of the federal government’s oil and gas leasing program and the parcels in question on February 4, 2009, just two weeks after taking office.

Five years later, the controversy over the 2008 Utah lease sale appears as a watershed moment for public land management in at least two regards. First, the outcry against the Bush administration’s decision signaled a growing divide between the public’s rising demand—particularly in the West—for more protections and recreational opportunities on public lands versus the Bush administration’s focus on maximizing oil and gas production at the expense of competing uses.

Though oil and gas have long been and continue to be an economic lynchpin in many Western communities, less than 2 percent of the region’s workforce is now in traditional natural resource sectors, such as mining, timber, and oil and gas, while more than 70 percent work in service-related sectors, according to research by Colorado College. With the outdoor recreation economy contributing billions of dollars to their states each year, voters now overwhelmingly see public lands as integral to their quality of life and attracting high-quality employers and good jobs.

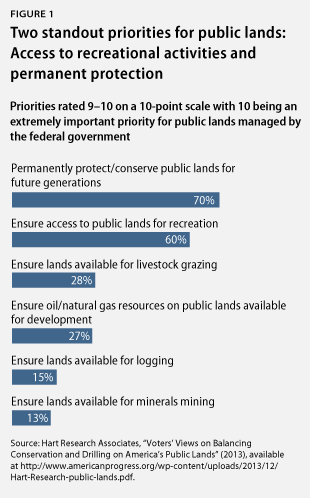

New research suggests that the public outcry against the Bush administration’s 2008 actions in Utah reflected broader public opinion trends in the West and nationally that continue today. At the request of the Center for American Progress, Hart Research Associates conducted more than 1,000 interviews with voters across the country from October 31 to November 4 to better understand the public’s preferred uses for public lands.

The researchers concluded that “Two pillars define what is at stake for public lands for voters across the country: permanently protecting public lands for future generations and ensuring access to recreational activities.” These priorities were most strongly felt in the West, where 74 percent of voters say the permanent protection of public lands is very important to them, and 65 percent say that ensuring recreational access is very important. In contrast, only 27 percent of voters nationally say that ensuring that public lands are available to oil and gas development is a high priority.

While the controversy and outcry over the 77 parcels in Utah were evidence of shifting public values, they also marked a turning point for the BLM’s approach to oil and gas management. Under the Bush administration, the BLM was tasked with implementing the recommendations of Vice President Dick Cheney’s Energy Task Force, which called for rewriting land-management plans to prioritize energy development, expediting or sidestepping environmental reviews, and doubling the oil and gas production on federal lands.

By the end of the Bush administration’s tenure, Western communities were weary of its oil and gas policies. “For years,” wrote the Salt Lake Tribune editorial board in early 2009, “Bush administration officials have been hell-bent on handing out drilling rights to energy companies with little regard for the long-term consequences of ravaging the natural landscapes of the West for short-term gain.”

The Obama administration’s oil and gas leasing reforms: A progress report

The Obama administration—led by then-Secretary of the Interior Ken Salazar—reviewed the 77 parcels of BLM’s oil and gas leasing program in early 2009. The findings were documented in reports by Deputy Secretary of the Interior David J. Hayes and by an interdisciplinary and interagency team of natural resource professionals. The reviewers found a leasing system that was overwhelmed: Agency professionals were under pressure to process leases faster than they could be appropriately reviewed, other values and uses on public lands were being discounted, and the oil and gas industry dominated the process. The program had become so controversial that 40 percent of all leasing parcels were formally protested by local communities, recreational users, and conservation organizations by 2008, up from just 1 percent in 1998. In Utah, New Mexico, Colorado, and Wyoming, the problem was even worse. A review by the Government Accountability Office found that 74 percent of all proposed leasing parcels in those four states from 2007 to 2009 were protested.

Based on these growing problems and the findings of the interdisciplinary review team, the Obama administration and the BLM launched the most significant reforms to the oil and gas leasing program in the agency’s 67-year history. The reforms help advance two fundamental philosophical changes for the agency:

- They affirm that, under the BLM’s multiple-use mission in the Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976, oil and gas development is to be balanced with other values and uses of public lands to ensure “the health and productivity of the public lands for the use and enjoyment of present and future generations.” “Under applicable laws and policies,” reads the BLM instruction memorandum implementing the reforms, “there is no presumed preference for oil and gas development over other uses.” This statement represented a major about-face after the culture and actions of the Bush administration’s BLM.

- The reforms call for a landscape-level approach to oil and gas planning and decision making. Under the reforms, the agency tells industry up front which areas of public lands are best suited for drilling, have the fewest environmental concerns, and minimize potential conflict with other high-value uses, such as recreation. This early planning approach is aimed at reducing the risk of costly and time-consuming conflicts that arise when industry nominates parcels—without good guidance from the agency—that prove to be highly controversial.

The BLM leasing reforms have begun to deliver promising returns since their issuance in May 2010. Only 10 percent of oil and gas lease sales were protested nationwide in 2011, and this rose to only 12 percent in 2012. Additionally, a higher percentage of the parcels nominated by industry are now being sold, suggesting that agency professionals are focusing their time and resources on nominations that are more likely to sell. Meanwhile, oil and gas production is still high. In fact, crude oil production on onshore federal lands was higher in each of the last four years than it was in 2008.

The BLM’s leasing reforms, however, should not be measured simply by the reduction of protests and lawsuits but by whether the agency’s decisions better reflect its statutory mandate and the public’s evolving priorities for the management of public lands. In this regard, whether the reforms have taken hold and, indeed, the management of public lands is coming more into line with the public’s priorities will be clear in the next year. In 2014, the BLM will face the most significant policy and management decisions it has encountered since 2009, when this administration took office.

We have identified six areas to watch over the coming year for indications of the success of the 2010 oil and gas leasing reforms and extent to which the 2008 Utah leasing controversy has spurred an enduring shift in principles and values within the BLM.

Master Leasing Plans

The 2010 leasing reforms created a new planning tool, called a Master Leasing Plan, or MLP, that BLM land managers are encouraged to use to identify which areas of the landscape are best suited for oil and gas leasing and which areas are to be protected for other uses such as recreation, hunting, and fishing. The BLM has identified 17 places where it will consider undertaking a master leasing plan, of which it has begun work on 13. Completing work on MLPs over the coming year will be a key milestone for the administration’s oil and gas leasing reforms. The outcome of the Moab MLP will be particularly important to watch, as it was the site of the 2008 leasing controversy in Utah and the protection of outdoor recreation opportunities is vital to the health of the area’s economy.

Resource Management Plans

The management of nearly 140 million acres of BLM lands will be under review and revision as part of the agency’s planning process in 2014. The BLM is required to update the plans for each of its 136 different management areas every 10 to 15 years. With so many Resource Management Plans under revision in the coming year, the BLM and the Obama administration have an opportunity to adjust to shifting public priorities, incorporate new science and information about the landscape, and better account for the economic and intrinsic values of protecting public lands from development.

Environmental protection rules

According to the Office of Management and Budget’s “Unified Agenda” released this fall, the BLM currently is at work on at least eight key rulemakings, four of which are aimed at reducing the environmental impacts of fossil-fuel extraction on public lands. These are:

- “Onshore Oil and Gas Order 9: Waste Prevention and Use of Produced Oil and Gas for Beneficial Purposes”: This rule would reduce and limit the amount of methane, a greenhouse gas more potent than carbon dioxide, released from oil and gas facilities on public lands. In particular, it would “establish standards to limit the waste of vented and flared gas.”

- “Hydraulic Fracturing”: To ensure that this widely used drilling practice is conducted with adequate protections for humans, water, and wildlife, this rule provides for public disclosure of chemicals used in the process and strengthens “regulations related to well-bore integrity.”

- “Onshore Oil and Gas Order 4: Oil Measurement”: This short but critically important rule would ensure that oil and gas extracted from federal lands is “accurately measured and reported,” in order to ensure that taxpayers are getting a fair return. It was last updated in 1989.

- “Oil Shale Management”: Oil-shale extraction technologies remain untested and unproven at the commercial scale. It is therefore important that this rule to guide the nation’s oil-shale program recognizes the speculative nature of the technologies, protects communities and water supplies during potential development, and enables the government to set an appropriate royalty rate if the technology is ever proven on a commercial scale.

In addition to finalizing these rules to provide protection to our air, water, land, and wildlife, we recommend that the BLM initiate a new rulemaking process to increase the royalty rate on oil and gas from public lands, which has not changed since 1920, to provide a fairer return for taxpayers.

Secretarial order on mitigation

Secretary Jewell proposed her first secretarial order in November, which established a “Department-wide mitigation strategy to ensure efficiency, consistency, conservation in infrastructure development.” This is an important first step, but work remains to develop agency-level policymaking to implement it. To make the secretarial order as effective as possible, the policy that the BLM develops should recognize that avoiding drilling in special places is the first step to an effective mitigation strategy.

Balancing drilling with land conservation

To provide a balanced approach to the management of public lands, the federal government should not only be working to provide opportunities for oil and gas development but also permanently protecting new areas for the public to use and enjoy. Unfortunately, the pace of land conservation has fallen behind the pace of oil and gas leasing in recent years. Since President Obama took office, 7.3 million acres of public lands have been leased to oil and gas companies for drilling, while only 2.9 million acres have been permanently protected. This imbalance is largely caused by Congress’s inability to pass the common-sense wilderness and national park bills that members of both parties have introduced. As a result, the Obama administration should respond to the desires of local communities by accelerating its efforts to permanently protect public lands using executive authority.

Sage-grouse protections

The fragmentation of the West’s iconic and vast sagebrush habitat over several decades has caused populations of the once ubiquitous greater sage grouse to collapse. As a result, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service will decide in 2015 whether the species should be protected under the Endangered Species Act. To provide better protections for the sage grouse and sagebrush habitat—on which hundreds of other species, including game such as elk and deer also rely—the BLM is revising 28 of its resource management plans. To avoid the need to list the species as threatened or endangered, these plan revisions will have to include strong protections for the sage grouse and set aside areas that are not to be developed or disturbed.

Conclusion

Interior Secretary Sally Jewell and the president’s nominees to lead the BLM and oversee land-management policy at the Department of the Interior are well prepared to address these six challenges and follow through on the reform agenda launched in the wake of the Utah leasing debacle.

In a recent speech at the National Press Club, Secretary Jewell reflected on what she called “a fundamental issue for Interior as a land manager: how we balance the inherent tensions that can exist with development and conservation.” She noted, “Part of the answer is encouraging development in the right ways and in the right places. Part of the answer is recognizing that there are some places that are too special to develop.”

The principles that Secretary Jewell articulated, if fully applied to the six areas to watch that we outline above, will help complete a BLM’s remarkable transformation in five short years, yield smarter and better oil and gas policies for the country, and forge a pillar of President Obama’s energy and conservation legacy.

Matt Lee-Ashley is a Senior Fellow at the Center for American Progress, focusing on energy, environment, and public lands. Jessica Goad is the Manager of Research and Outreach for the Center’s Public Lands Project.