Having savings is key to basic economic security. In fact, a 2010 Urban Institute analysis found that in nonelderly households, even a small amount of savings—less than $2,000 in liquid assets—makes families significantly less likely to face economic hardships such as food insecurity, forgone doctor visits, missed housing or utility payments, and shut-off utilities, compared to those who have zero savings. For households holding between $2,000 and $10,000 in liquid assets, this effect was twice as large.

Coming up with even small amounts of savings, however, poses a challenge for many Americans, especially those with lower incomes. About two in five American families report that they would “probably not” or “certainly not” be able to come up with $2,000 in 30 days to deal with an emergency such as a car repair, according to the FINRA Investor Education Foundation’s 2012 National Financial Capability Study. For low-income families, young people, and people of color, the lack of economic security is even greater. Among the bottom third of American families by income, 68 percent report that they would be unable to come up with $2,000 in 30 days. Forty-nine percent of those Americans ages 18 to 34, 50 percent of African Americans, and 47 percent of Latinos also report that they would be unable to come up with $2,000 in 30 days.

Many federal and state policies already include ways to encourage more savings from lower-income households. There are also a number of proposals to do more to help lower-income households get more economic security. Our review of existing policies and proposals shows that the most effective savings matches typically follow a few basic principles:

- They are progressive, with the lowest-income savers receiving the largest incentives.

- They are structured to create meaningful incentives.

- They are available for a wide variety of savings goals.

- They are delivered through refundable tax credits—credits that do not depend on the amount of federal income tax a saver owes.

These policies and proposals aim to make the federal tax code more progressive, countering the upside-down nature of current savings incentives that disproportionately favor high-income earners, who need the least help in saving more.

The problem of households not accumulating more savings for emergencies and longer-term goals such as retirement is not due to a lack of tax incentives to save more. On the contrary, the federal government annually forgoes billions of dollars to encourage people to save more through various provisions in the tax codes. Many of these incentives, however, do not reach those who would benefit the most. Indeed, an estimated $158 billion in forgone tax revenue goes toward retirement savings plans, of which the vast majority of incentives—80 percent—flow to the top 20 percent of income earners. Another $2 billion goes toward college savings plans, yet 70 percent of families with these education savings accounts earn more than $100,000 annually, placing them among the top 22 percent of U.S. households in terms of earnings.

One main reason why existing tax incentives fail to reach most working families is that as deductions, rather than credits, their benefits are far lower than they would be for higher-income earners. For example, a married couple earning $53,000 per year—roughly the national median—is in the 15 percent tax bracket, so each $1 saved in a 401(k) plan reduces that family’s tax burden by 15 cents. But for a couple earning $200,000—in the 28 percent tax bracket—each $1 saved reduces their tax burden by 28 cents. Tax filers in the highest bracket see their tax burden reduced by 39.6 cents for every $1 they save. In other words, the middle-class family earning $50,000 needs to save nearly $7 to lower their taxes by $1, but the family earning $200,000 only has to save about $3.57, and the family in the highest bracket only about $2.53 to get the same tax benefit.

Some potential low-income savers also fail to benefit from existing tax provisions because they are not refundable—in other words, the tax incentives are not available if they exceed the federal income tax that the taxpayer owes. Only about $1 billion annually goes toward the low-income Saver’s Credit, designed to boost retirement savings for working families earning up to $57,000 per year—and many families are ineligible or receive only a fraction of the maximum credit. Some working families pay no federal income tax at all—though they do pay payroll taxes—and are hence not eligible for the Saver’s Credit. Low-income families who struggle daily to get by should not be forced to pay federal taxes beyond their means. At the same time, however, these families do not benefit from tax breaks designed to help them build economic security because their marginal tax bracket is 0 percent.

The Center for American Progress recently released a report on reforming the multitude of tax deductions for savings with a single, flat, and refundable credit—a Universal Savings Credit. This would equalize the playing field for savers of all incomes by offering the same credit to everyone. In the above example, instead of the high-income family saving $1 in tax liability for every $2.50 saved—a far better deal than the $1 of tax reduction for every $7 saved by a middle-income family—all families would receive the same tax benefit.

The existing evidence suggests that shifting tax incentives to lower-income earners relative to the current system of tax incentives will increase savings among lower-income savers. It hence stands to reason that strengthening savings incentives for lower-income savers beyond a flat credit for all through progressive matches could help them save even more. But even in the existing tax code, Congress could add progressive savings matches as a first step to counter the upside-down nature of current savings incentives.

This issue brief consequently summarizes existing matches and novel proposals to expand them to inform the discussion around making savings incentives work better for the lower-income households who need them the most.

The landscape of existing savings matches

Matching provisions already exist in several familiar savings vehicles: employer-based retirement plans and college savings plans. These plans, however, are often less accessible to low-income savers. Two-thirds of workers making $75,000 or more per year participate in an employer-sponsored retirement plan, but less than one-third of workers earning less than $30,000 participate. And they often fail to share in the tax benefits because their incomes are lower.

Employer-based retirement plans

Retirement plans with matching features are only available to a subset of American workers, but they represent a major precedent. According to the 2010 Survey of Consumer Finances, only about half of all American families have a retirement account, and only 35 percent of families have an employer-based account such as a 401(k) plan. The vast majority of retirement plans, however, offer some type of match. For example, four out of five plans administered by Vanguard, the world’s largest mutual-fund company, offer some type of match; 95 percent of participants in Vanguard plans receive a match, since the plans that offer a match tend to be larger than those that do not. Similarly, a survey by consulting firm Aon Hewitt of 141 plans of large companies employing more than 3.5 million people found that 96 percent of plans offered some type of matching contribution in 2012.

Matches generally range from a 25 percent match to a 100 percent match on the first 3 percent to 6 percent of pay that is saved in a plan; the median matching plan offers a 50 percent match on the first 5 percent saved, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’s 2010 National Compensation Survey. On average, matching provisions add a maximum of 3.5 percent of one’s income to a retirement plan. Over time, this can both incentivize savings behavior and greatly increase account balances.

Matching funds have generally succeeded in increasing employee participation in retirement savings plans and have, to some extent, increased contributions. Fidelity Investments reported in 2009, for example, that introducing an employer match can boost employees’ participation in retirement plans by up to 9 percentage points. The matching limit functions as a type of behavioral target: Consumers are likely to save up to the maximum amount that is matched but are less likely to save above that level. Indeed, Fidelity found that about 30 percent of participating employees save at the maximum match level. This means that in companies with relatively low matching limits, savings may be encouraged, but overall savings may decrease.

College savings plans

The federal government offers tax incentives for education savings through two plans:

- Section 529 plans, which are administered by individual states to support higher-education expenses

- Coverdell accounts, which are available on the private market to support a family’s expenses for both K-12 and higher-education costs

Both of these plans are used predominantly by higher-income savers. According to the 2010 Survey of Consumer Finances, less than 3 percent of families have an education savings account such as a Section 529 or Coverdell account. The median income of families using 529 plans or Coverdell accounts is about $142,400—nearly three times as high as the national median. What’s more, families saving through these plans have median wealth 25 times as high as that of families who are not using these plans.

Over the past decade, states have begun to match working families’ contributions to Section 529 plans as a way to encourage broader participation in these plans; so far, 11 states have introduced matching provisions into their Section 529 plans. Louisiana offers a modest match, called an “earnings enhancement,” to its 529 plan, from 14 percent of contributions for families earning less than $30,000 to 2 percent of savings for families earning more than $100,000. Generally, other states offer matching contributions for the first $300 to $500 that low- and moderate-income residents contribute to their state’s college savings plan, with income phaseouts ranging from approximately $40,000 to $100,000 of annual income. These phaseouts may also vary by family size. Rhode Island and Arkansas have the most attractive match rates, offering up to a 2-1 match. While $500 is a significant amount for a low-income family to save during the year—with the average Earned Income Tax Credit, or EITC, refund exceeding $2,000—contributing $500 to a 529 plan using a tax refund would be a modest way to leverage the additional $1,000 in matching funds toward that family’s college savings.

Sustainable funding of matching programs can be a major barrier to states looking to match contributions to their 529 plans. Because the state legislature must appropriate matching funds in advance of the money being spent, some states have a cutoff for the number of residents who can apply for a match; in Kansas, for instance, only the first 1,200 participants are eligible. This also means that matches may not be predictable for savers from one year to the next.

In some cases, private or nonprofit-funded matches have helped overcome this challenge. In San Francisco, the privately funded Kindergarten to College initiative also offers matching funds for children in the city’s public schools. Since 2011, entering kindergarteners have been automatically enrolled in the program. For the first $100 saved, an additional $100 is deposited in the account, with an additional $100 bonus for families that save a minimum of $10 per month for six months.

Individual Development Accounts

For nearly two decades, Individual Development Accounts, or IDAs, have demonstrated that low-income families can save when given the right incentives and structures. The American Dream Demonstration—the first large-scale pilot program of these accounts—delivered these matched savings accounts to 2,350 participants in 14 locations nationwide between 1997 and 2003. Participating families with incomes not exceeding twice the federal poverty line—roughly $39,000 for a family of three today—were offered at least a dollar-for-dollar match on their savings toward goals such a down payment for a first home, some form of higher education, or starting a small business. More than half of all participants saved at least $100 while in the program, with about 15 percent of participants receiving the maximum 1-1 match—$2,050 on average—by continuing to save regularly over a two- to three-year period.

Nonprofit organizations receive federal funding for IDA programs through the Assets for Independence, or AFI, competitive grant process at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Why progressive matches are the right way forward

A lack of savings can lead to greater economic hardship, magnifying the effects of losing a job, dealing with a car breakdown, or recovering from a medical condition. At the same time, saving can be quite difficult. About 26 percent of American households lack sufficient resources to get by at the poverty line for three months in the event of job loss or other sudden financial shock. Excluding the value of homes and vehicles, this number increases to 44 percent—roughly three times the federal poverty line. Indeed, 27 percent of Americans report not having any emergency savings at all.

There is evidence, however, that low-income earners can indeed save money under the right circumstances. One of the largest matched savings experiments took place at H&R Block offices in metropolitan St. Louis, Missouri, in 2005. The company randomly offered 14,000 low-income tax filers no match, a 20 percent match, or a 50 percent match on their savings if they opened a retirement savings account known as an Express IRA. Only 3 percent of those not offered a match opened accounts, but 8 percent opened accounts in the 20 percent match group, and 14 percent opened accounts in the 50 percent match group—making them nearly five times as likely to save as those without a match. Savers offered a match also contributed four to eight times as much money to their accounts as did savers not offered a match.

Beginning in 2010, a similar pilot program took place in four cities with support from the U.S. Social Innovation Fund. Low-income tax filers at volunteer tax preparation sites in New York; Newark, New Jersey; San Antonio, Texas; and Tulsa, Oklahoma, were randomly offered a 50 percent match on the first $1,000 saved, provided that they did not touch their savings for approximately one year. Most participants who were offered a match opted to save, and about two-thirds were able to hold onto the savings for a year to receive the matching contribution.

Yet most savings incentives are the result of federal tax deductions that reduce one’s taxable income, rather than directly match savings. Contributions made to a tax-advantaged retirement account, for example—such as a 401(k) plan or an Individual Retirement Arrangement, or IRA—do not count as taxable income, resulting in a smaller tax liability. The money in these accounts also accumulates without the earnings being taxed, though taxes must be paid on the amount withdrawn for retirement or other permitted purposes. Similar tax benefits exist for savings plans designed to cover health care or college costs.

Because these incentives come from tax deductions, the size of the incentive depends on the saver’s tax bracket. Taxpayers earning more than $400,000 individually, or $450,000 jointly, are subject to the highest tax bracket, 39.6 percent, for every $1 earned above that level. But for every $1 placed in a tax-advantaged savings vehicle, their tax liability is reduced by 39.6 cents. Lower-income workers are in a lower tax bracket, resulting in both a smaller tax burden for each additional $1 earned and a much smaller savings incentive of 15 or 25 cents for every $1 saved, instead of 39.6 cents. And low-income working families have no income tax liability at all, though they do pay payroll taxes. While the current tax system ensures that they are not unfairly taxed, it also leaves them with no incentive to save—even though savings could potentially increase their economic security.

Not only do higher-income workers have a greater tax benefit, they also have greater access to tax-advantaged savings vehicles. For example, 32.4 percent of workers earning between $20,000 and $30,000 annually participate in a retirement savings plan at work, and fewer than one in seven workers earning less than $20,000 participates in such plans, while two-thirds of workers earning more than $75,000 participate. Ultimately, these tax incentives contribute to an imbalanced system of federal efforts to encourage savings through the tax code: 80 percent of the benefits from retirement tax incentives go to those in the top fifth of the income distribution.

Despite greater access and stronger incentives for higher-income earners, academic research shows that these incentives often fail to create new savings. For low-wealth households, 401(k) plans and other tax-advantaged savings vehicles often represent new savings, but among higher-income earners, 401(k) plans and other tax-advantaged savings vehicles largely capture savings that would have happened anyway even without these plans.

Federal and state policymakers have long considered savings matches an alternative that could incentivize families to start saving and to potentially save more than they otherwise would. After all, working families may not benefit as much from tax deductions for saving—if they benefit at all.

Principles of matching incentives moving forward

Matching incentives already exist in some retirement and college savings programs, but these incentives have limitations. Meanwhile, the federal government continues to subsidize savings through tax expenditures, even though these benefits are not widely shared. The following four principles would make matched savings a more effective piece of federal savings policy:

- Matching funds should be progressive so that savings incentives are greater for those who need the greatest push. The current upside-down nature of tax incentives provides greater benefits to savers who do not generate new net savings and little to no benefit to those for whom small amounts of savings can be transformative.

- Progressive matches should be structured in a way that maximizes savings behavior at targeted levels. To act as a true incentive, matches should be clear and sizable. Employer matches typically range from 25 percent to 100 percent of contributions, and state matches in college savings plans range from 50 percent to 200 percent. Meanwhile, a 2011 study by William G. Gale, co-director of the Tax Policy Center, found that a 30 percent refundable tax credit, delivered as a match, would be revenue-neutral to current law. Matching levels will ultimately depend on available funds, applicable eligibility ranges, and future research.

- Progressive matches should be available for a wide number of savings goals rather than restricted to a specific purpose such as education or retirement. Many Americans tap their 401(k) retirement accounts either by borrowing from their savings plans or withdrawing money before retirement. That is, savings objectives may shift over time as people’s situations change.

- Progressive matches should be delivered through refundable tax credits to ensure an automatic and consistent distribution of incentives. Current matching provisions are either voluntary or dependent on annual budget appropriations. This lack of consistency limits their usefulness. Refundable tax credits are an automatic way to deliver matching funds to all eligible Americans, including those with no income tax liability. And refundable tax credits are the only way to deliver credits consistently through the tax code and also reach the low-income earners who are most financially vulnerable.

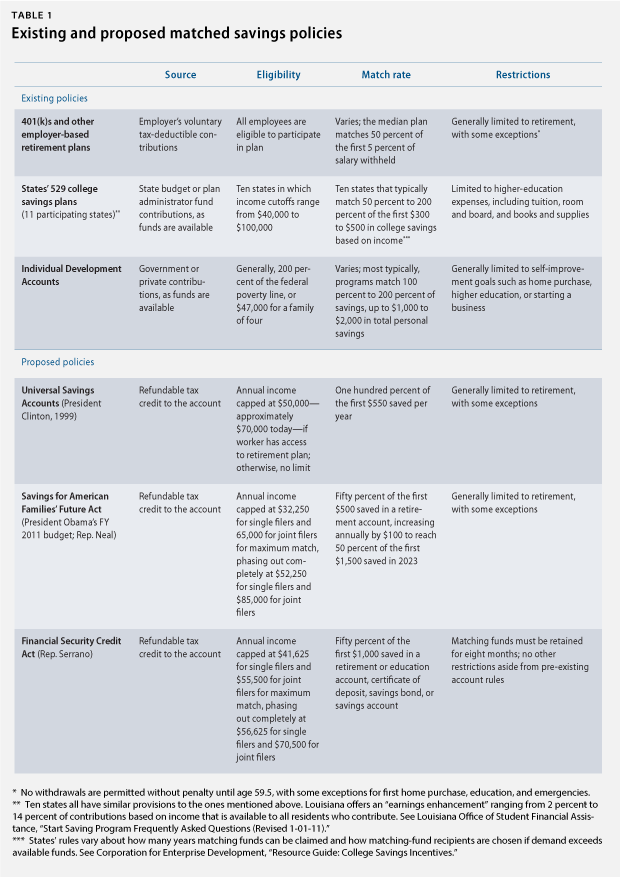

Various federal matching proposals have incorporated these principles to some extent. Table 1 compares current matched savings programs with federal proposals to illustrate how these principles could better be met.

Nearly two decades ago, President Bill Clinton proposed a new system of savings known as Universal Savings Accounts, or USA Accounts, to provide an additional basic level of retirement security in addition to Social Security benefits. Workers could contribute up to $1,500 per year to these accounts, which would include an automatic contribution of $400 per year for the lowest-income workers and 100 percent matching contributions of the first $550 saved by workers. Workers earning more than $50,000 annually would only be eligible for matching funds if they did not have access to a retirement plan at work. The annual cost of this savings initiative was estimated to be about $36 billion—about $48 billion in today’s dollars.

On a more modest scale, President Barack Obama’s fiscal year 2011 budget included a proposal that would expand eligibility for the Saver’s Credit to joint tax filers earning as much as $85,000—rather than today’s $57,500 limit—and convert it to a refundable credit so that all tax filers, not just those with a positive tax liability, could potentially benefit. These changes would cost an estimated $3 billion annually, in place of the $1 billion cost of the existing Saver’s Credit.

Recent proposals in Congress would similarly enhance savings incentives with an explicit focus on matching contributions. This year, a bill sponsored by Rep. Richard Neal (D-MA)—the Savings for American Families’ Future Act, or H.R. 837—would have also expanded eligibility for the Saver’s Credit and would have directly deposited the credit into the taxpayer’s retirement account, effectively making it a match.

Federal proposals have largely focused on retirement, though withdrawals from retirement accounts are permitted in some circumstances for first-time homeownership or higher-education expenses. But some proposals have looked to incentivize savings more broadly. The Financial Security Credit Act, or H.R. 2917, introduced in August 2013 by Rep. José Serrano (D-NY), would offer a 50 percent match on the first $1,000 saved by low- and moderate-income workers—single filers earning less than $41,650 and joint filers earning less than $55,000—in a retirement account, education savings account, U.S. savings bond, certificate of deposit, or even some savings accounts, provided that families held onto the savings for at least eight months.

Conclusion

The lack of savings among low- and moderate-income families threatens both their ability to get by in emergencies and their potential to plan for the future. Yet the tax code is largely focused on incentives for high-income savers—those who may not need help saving in the first place.

The Universal Savings Credit, by equalizing tax benefits across all incomes and savings vehicles, would make saving simpler and more attractive for working families. Introducing a progressive match for low-income savers in conjunction with the Universal Savings Credit would further help families start saving and accumulate more savings to build their own financial security. Even under the current tax code, adding progressive matches would create a fairer tax system that rewards saving by those for whom savings are most important.

Instead of continuing tax expenditures that benefit the highest-income savers, this approach would ensure that forgone tax revenue goes to help build and expand the middle class.

Joe Valenti is the Director of Asset Building at the Center for American Progress. Christian E. Weller is a Senior Fellow at the Center and a professor in the Department of Public Policy and Public Affairs at the University of Massachusetts Boston.